Abstract

Although idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome(IHES) commonly involves the lung, it is rarely associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Here we describe a case of IHES presented in conjunction with ARDS. A 37-year-old male visited the emergency department at Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, with a chief complaint of dyspnea. Blood tests showed profound peripheral eosinophilia and thrombocytopenia. Patchy areas of consolidation with ground-glass opacity were noticed in both lower lung zones on chest radiography. Rapid progression of dyspnea and hypoxia despite supplement of oxygen necessitated the use of mechanical ventilation. Eosinophilic airway inflammation was subsequently confirmed by bronchoalveolar lavage, leading to a diagnosis of IHES. High-dose corticosteroids were administered, resulting in a dramatic clinical response.

Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (IHES) is a group of disorders characterized by the overproduction of eosinophils resulting in inflammatory damage to multiple organs, including skin, heart, lung, gastrointestinal tract, and nervous system.1 Signs and symptoms associated with lung involvement are relatively common, occurring in approximately 40% of IHES patients.2,3 However, despite frequent lung involvement, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is rarely seen in conjunction with IHES, with only a few cases described in the literature to date.4,5 This is the first case report of IHES presented with ARDS in Korea.

A 37-year-old male visited the emergency department at Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, presenting with a chief complaint of dyspnea. Initial symptoms had begun 1 week prior to his visit, characterized by fever and chills, followed by progressive respiratory difficulty. He appeared acutely ill. A crackling sound was heard upon chest examination. His heartbeat was regular without a murmur. A purplish discoloration of the right ankle was observed, but there were no local heat or tenderness. Initial blood pressure was 163/91 mmHg, pulse rate was 114 beats/min, respiratory rate was 24 breaths/min, and body temperature was 38℃. Oxygen saturation was initially detected as 87%, and increased to 95% upon oxygen supplement via nasal cannula at 5 L/min. Following oxygen supplementation, arterial blood gas analysis (ABGA) showed a pH of 7.39, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) of 40.9 mmHg, partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) of 113.7 mmHg, and oxygen saturation of 98%.

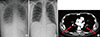

Laboratory tests revealed peripheral eosinophilia and thrombocytopenia with a white blood cell count of 22,580/µL (50% neutrophils, 31% eosinophils, 10% lymphocytes), Hb levels at 13.7 g/dL, and a platelet count of 26,000/µL. Prothrombin and activated partial thromboplastin times were 15 sec, and 35.4 sec respectively. Fibrinogen levels were within the normal range, but the concentration of D-dimer was markedly elevated at 26.69 µg/mL. Serum total IgE and ECP levels (939.4 IU/mL and 201.0 ng/mL, respectively) were both elevated, too. Tests for both anti-nuclear antibodies and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. A test for parasites in the stool and serum were negative. Bone marrow biopsy showed normal cellularity with increased eosinophils. Fip1-like1 and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (FIP1L1-PDGFRA) gene fusion was not detected. Patchy consolidation with ground-glass opacity in both lower lung zones was noticed in the initial chest radiography (Fig. 1A).

During the initial workup, the patient became progressively tachypneic with increased oxygen demand to 15 L/min via facial mask. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit and oxygen supply was increased to 100% by high-flow nasal cannula. Despite supplementation, PaO2 levels remained low (49.9 mmHg) leading to a diagnosis of ARDS, and then the patient underwent intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) revealed marked eosinophilia (187/200 evaluated cells, 93.5% eosinophils). Skin biopsy of the right ankle showed diffuse eosinophilic perivascular infiltration of the dermis (Fig. 2A) and eosinophilic abscess of subcutaneous fat (Fig. 2B). Duplex sonography revealed deep vein thrombosis in the left popliteal, soleal, and peroneal veins. Nerve conduction test and electromyography showed neuropathy in the right posterior tibial nerve.

A diagnosis of IHES was reached based on the presence of peripheral and tissue eosinophilia, along with the exclusion of other causes of eosinophilia. High-dose corticosteroid (methylprednisone 1 mg/kg/day) therapy was initiated on the first day of admission. By day 3, eosinophil counts decreased to the normal range (Fig. 3). Extubation was performed on day 4 as a result of clinical and radiological improvements.

A chest CT scan was obtained on day 9 to evaluate symptoms of mild dyspnea despite the dramatic improvement seen by simple radiography (Fig. 1B). Pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) was detected in the bilateral lobar and segmental branches of the pulmonary arteries (Fig. 1C), and we started anticoagulant therapy. On day 23, the patient was discharged from the hospital with a gradual tapering of corticosteroids.

In 1975, Chusid et al.6 established the basic guidelines for diagnosis of IHES, which is still in use today. Criteria include blood eosinophilia>1,500 cells/µL for longer than 6 months, lack of evidence for parasitic, allergic, or other known causes of eosinophilia, and the presence of organ damage or dysfunction related to hypereosinophilia. However, recently these criteria have been changed; when marked eosinophilia and obvious tissue damage such as cardiac involvement are observed, the initiation of treatment is recommended regardless of the duration of eosinophilia.7 Our case fulfills the diagnostic criteria for IHES except the duration of peripheral eosinophilia.

Lung involvement is relatively common in IHES. In a previous study, of 49 patients with IHES, 63% had more than one kind of respiratory symptoms, and 43% showed abnormal findings by chest radiography or CT scan.8 However, despite the fact that lung is frequently involved in IHES, there have been only a few cases that have presented ARDS. ARDS is an acute and diffuse inflammatory lung injury that leads to increased pulmonary vascular permeability, increased lung weight, and a loss of aerated tissue.9 Approximately 60 distinct etiologies including eosinophilic pneumonia have been recognized for ARDS, among which severe sepsis and bacterial pneumonia are the most common.10-14

Our patient presented fever and dyspnea initially, and chest radiography showed bilateral parenchymal infiltration. Intubation was performed due to ARDS, and bronchoscopic examination with BAL revealed profound alveolar eosinophilia. The main cause of ARDS was thought to be severe eosinophilic parenchymal inflammation of the lungs. This diagnosis was confirmed by rapid clinical and radiologic response to high-dose corticosteroid therapy.

Thromboembolic complication is a common cause of mortality and morbidity in patients with IHES. About 25% of IHES patients experience thromboembolisms, with a mortality rate of 5%-10%.15 In this case, a chest CT scan on hospital day 9 revealed a thromboembolism in the bilateral pulmonary arteries. PTE was suspected considering the initial presentation, which included purplish discoloration of the right ankle, thrombocytopenia, D-dimer elevation, and deep vein thrombosis in the left popliteal, soleal, and peroneal veins. However, the marked eosinophilia in BAL fluid and the dramatic response to corticosteroid therapy prior to initiation of anticoagulant therapy suggest that primary cause of respiratory failure is parenchymal lung involvement of IHES, rather than PTE.

Corticosteroids are a first-line therapy for FIP1L1-PDGFRA-negative IHES.16,17 About 85% of patients on corticosteroid therapy reach partial or complete remission by 1 month.17 For patients not responding to corticosteroids, second-line therapies such as hydroxyurea, interferon-α, anti-IL5 antibodies, or anti-CD52 antibodies can be considered.18 In the present case, peripheral eosinophilia and involvement of the skin and lung were successfully treated by high-dose corticosteroid alone.

In summary, we describe a rare case of IHES with ARDS due to eosinophilic lung involvement, which showed a dramatic response to high-dose corticosteroid therapy.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) Patchy areas of consolidation with ground-glass opacity are observed in both lower lung zones on the initial chest radiograph. (B) Follow-up chest radiograph on hospital day 9 shows a dramatic decrease of lung infiltrate. (C) Chest CT scan shows bilateral acute pulmonary thromboembolism (arrows) involving both pulmonary arteries.

Fig. 2

Skin biopsy of the purpuric lesions of the right ankle shows (A) diffuse eosinophilic perivascular infiltration in the dermis and (B) eosinophilic abscess in the subcutaneous fat (H&E stain, ×40 magnification).

Fig. 3

Platelet counts, eosinophil counts, and D-dimer levels during hospitalization. Following initiation of high-dose corticosteroid therapy, eosinophil counts decreased to normal levels by day 3, and platelet counts progressively recovered. D-dimer levels initially elevated, but began to decrease with anticoagulant therapy. HD, hospital day.

References

1. Klion A. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: current approach to diagnosis and treatment. Annu Rev Med. 2009; 60:293–306.

2. Fauci AS, Harley JB, Roberts WC, Ferrans VJ, Gralnick HR, Bjornson BH. NIH conference. The idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Clinical, pathophysiologic, and therapeutic considerations. Ann Intern Med. 1982; 97:78–92.

3. Spry CJ, Davies J, Tai PC, Olsen EG, Oakley CM, Goodwin JF. Clinical features of fifteen patients with the hypereosinophilic syndrome. Q J Med. 1983; 52:1–22.

4. Roufosse F, Goldman M, Cogan E. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative variants. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006; 27:158–170.

5. Winn RE, Kollef MH, Meyer JI. Pulmonary involvement in the hypereosinophilic syndrome. Chest. 1994; 105:656–660.

6. Chusid MJ, Dale DC, West BC, Wolff SM. The hypereosinophilic syndrome: analysis of fourteen cases with review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1975; 54:1–27.

7. Simon HU, Rothenberg ME, Bochner BS, Weller PF, Wardlaw AJ, Wechsler ME, Rosenwasser LJ, Roufosse F, Gleich GJ, Klion AD. Refining the definition of hypereosinophilic syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 126:45–49.

8. Dulohery MM, Patel RR, Schneider F, Ryu JH. Lung involvement in hypereosinophilic syndromes. Respir Med. 2011; 105:114–121.

9. ARDS Definition Task Force. Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012; 307:2526–2533.

10. Pepe PE, Potkin RT, Reus DH, Hudson LD, Carrico CJ. Clinical predictors of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Surg. 1982; 144:124–130.

11. Hudson LD, Milberg JA, Anardi D, Maunder RJ. Clinical risks for development of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995; 151:293–301.

12. Fowler AA, Hamman RF, Good JT, Benson KN, Baird M, Eberle DJ, Petty TL, Hyers TM. Adult respiratory distress syndrome: risk with common predispositions. Ann Intern Med. 1983; 98:593–597.

13. Villar J, Blanco J, Añón JM, Santos-Bouza A, Blanch L, Ambrós A, Gandía F, Carriedo D, Mosteiro F, Basaldúa S, Fernández RL, Kacmarek RM. ALIEN Network. The ALIEN study: incidence and outcome of acute respiratory distress syndrome in the era of lung protective ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2011; 37:1932–1941.

14. Doyle RL, Szaflarski N, Modin GW, Wiener-Kronish JP, Matthay MA. Identification of patients with acute lung injury. Predictors of mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995; 152:1818–1824.

15. Ogbogu PU, Rosing DR, Horne MK 3rd. Cardiovascular manifestations of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007; 27:457–475.

16. Park YM, Bochner BS. Eosinophil survival and apoptosis in health and disease. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010; 2:87–101.

17. Ogbogu PU, Bochner BS, Butterfield JH, Gleich GJ, Huss-Marp J, Kahn JE, Leiferman KM, Nutman TB, Pfab F, Ring J, Rothenberg ME, Roufosse F, Sajous MH, Sheikh J, Simon D, Simon HU, Stein ML, Wardlaw A, Weller PF, Klion AD. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: a multicenter, retrospective analysis of clinical characteristics and response to therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 124:1319–1325.e3.

18. Park SM, Park JW, Kim SM, Koo EH, Lee JY, Lee CS, Choi DC, Lee BJ. A case of hypereosinophilic syndrome presenting with multiorgan infarctions associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2012; 4:161–164.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download