Abstract

The diagnosis of anaphylaxis is often based on reported symptoms which may not be accurate and lead to major psychosocial and financial impacts. We describe two adult patients who were diagnosed as having recurrent anaphylaxis witnessed by multiple physicians based on recurrent laryngeal symptoms. The claimed cause was foods in one and drugs in the other. We questioned the diagnosis because of absent documentation of objective findings to support anaphylaxis, and the symptoms occurred during skin testing though the test sites were not reactive. Our initial skin testing with placebos reproduced the symptoms without objective findings. Subsequent skin tests with the suspected allergens were negative yet reproduced the symptoms without objective findings. Disclosing the test results markedly displeased one patient but reassured the other who subsequently tolerated the suspected allergen. In conclusion, these 2 patients' symptoms and evaluation were not supportive of their initial diagnosis of recurrent anaphylaxis. The compatible diagnosis was Munchausen stridor which requires psychiatric evaluation and behavior modification, but often rejected by patients.

Anaphylaxis can be misdiagnosed when based on only symptoms, particularly if occurred multiple times. We describe 2 cases that illustrate the complexity of presentation and approaches for evaluation. Both patients claimed strong symptoms, initially and repeatedly, that led to the diagnosis of anaphylaxis. However, the diagnosis was reconsidered after a careful review of the reported medical history and physical findings. Conducting appropriately-designed challenge tests ruled out the diagnosis of anaphylaxis.

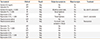

A 51-year-old nurse reported 8 episodes of anaphylaxis over 5 months and most required ambulance transfer to hospital. They occurred while eating but no particular foods were suspected. At least 6 episodes were witnessed by physicians, and emergency treatment resulted in rapid resolution. Each episode comprised feeling throat obstruction, stridor, and occasional pruritus, but no rash or hypotension. One episode occurred at work and was treated by her employer physicians. She was evaluated by a local allergist (Table 1). Skin prick testing (SPT) on two visits was negative, but on both occasions she developed severe stridor that immediately resolved with epinephrine. She was referred to our clinic to identify the cause.

Our history-taking revealed she had numerous hospital admissions for a variety of medical and surgical reasons. She has been a divorcee for 25 years and living alone. She admitted work-related stress, and was recently placed on disability because of concern about the risk of fatal anaphylaxis at work. Her physical examination did not reveal any abnormal findings. She agreed on performing "certain" allergy tests on stages and the results to be discussed at the end. While being monitored, SPT was done with normal saline on 4 sites and histamine on 2 sites. She immediately developed severe stridor, without pruritus, rash, gastrointestinal symptoms, or dizziness. She maintained normal vital signs, blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and peak expiratory flow rate. She demanded immediate epinephrine injection. Her symptoms resolved immediately upon injecting 0.1 mL normal saline. On her second visit, after applying SPT with 16 food extracts she exhibited stridor and insisted on receiving epinephrine. Again, 0.1 mL normal saline injection resulted in immediate resolution. On her third visit, SPT with 16 other food extracts were negative and she had no symptoms. The nature of tests were tactfully revealed but she exhibited displeasure. We discussed the possibility of vocal cord dysfunction to be evaluated at her city, which was ruled out and no anatomic abnormality was noted. She angrily rejected psychiatric evaluation.

Case 2 is a 42-year-old policeman whose work exposed him to skin contact with narcotics. At age 35, 2 days after receiving oxycodone and hydrocodone for an injury he reported transient rash on one arm. Post-surgery (placing shoulder plate), immediately after receiving hydromorphone complained of throat swelling and breathing difficulty that resolved after epinephrine intramuscularly and corticosteroids. A few hours later, immediately after a dose of oxycodone he reported the same symptoms. He was transferred to the ICU and improved after IV diphenhydramine, ranitidine and methylprednisolone. He was discharged next day on acetaminophen and prescription for epinephrine auto-injector , and was advised to avoid all narcotics.

Three years later, he felt throat tightness after administering a morphine-containing tablet to his dog. A few months later, he touched his lips after handling methamphetamine then felt local numbness and throat tightness. He administered epinephrine and went to the emergency department where he received prednisone though he had normal vital signs and physical examination. He was referred for allergy evaluation (Table 2) because he became concerned about occupational exposure or future need for pain medications or local anesthetics (he believed related to narcotics). He showed negative skin tests to fentanyl and xylocaine, yet within 5 minutes of application he felt his mouth as "cotton balls" and throat tightness, but no objective signs. He improved following epinephrine, then chlorpheniramine and solumedrol. On another visit, skin testing with bupivacaine was negative, yet he complained of throat tightness. He seemed anxious during testing. Normal saline intradermal test reproduced throat symptoms. After he was informed of the nature of the test and reassured, the symptoms quickly subsided spontaneously.

After he was reassured, his fear was alleviated and testing with novocaine and bupivacaine was negative and had uneventful titrated subcutaneous challenge with up to 2 mL of each. He underwent a procedure using 2 local anesthetics without any symptoms. He remained concerned about future potential risk from pain medications. He passed intradermal re-testing with fentanyl then uneventful titrated subcutaneous challenge. He had normal pre-test serum histamine (<1.5 ng/mL) and tryptase (4 ng/mL). Skin testing was not done with opioids because of their direct histamine release.

Munchausen syndrome is a psychiatric factitious disorder in which the subject repeatedly pretends to be sick or gets sick on purpose to gain attention. It is probably much more common than being identified. After the first report in 1951,1 only a few cases were reported, with the last was in 1999.2 In the mid-seventies, a few cases were described,3,4 including one woman with >15 hospital admissions. The vast majority of cases were young to middle age adult females.5,6 There seems to be predominance of health care professionals,7 reflecting their ability of reporting convincing history and imitate symptoms. One woman received treatment for anaphylaxis at multiple emergency departments and hospital admissions in different cities and on two occasions received assisted ventilation.2 In addition to the absence of objective findings, extensive tests were normal. She developed symptoms upon challenge with placebo but not with the claimed allergen (tartrazine). A careful review of her past medical records revealed a psychiatric illness.

Our two patients were misdiagnosed as recurrent anaphylaxis by multiple physicians and even during allergy testing that was negative. In a literature review, Wong2 noticed that 4 case-reports by different authors were apparently on the same patient. Such behavior may be used to seek attention for emotional gratification or to manipulate others. To avoid a bias, the patient should be just informed at the beginning that "some tests will be done during a few visits and the results will be discussed at the end." It is prudent to start testing with placebos. Positive tests for allergens should be evaluated by single-blind, placebo-controlled methods. Tactful approach is needed in disclosing the negative results of allergy testing. It is also prudent to rule out vocal cord dysfunction, which usually has an underlying psychologic component.8 Patients often angrily reject psychiatric evaluation and the problem continues, whereas those who accept are usually successfully rehabilitated by behavior modification.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Allergy tests in a woman with claimed "recurrent anaphylaxis to food" (case 1)

Table 2

Allergy tests in a man with "recurrent laryngeal stridor to narcotics and local anesthetics" (case 2)

References

1. Asher R. Munchausen's syndrome. Lancet. 1951; 1:339–341.

2. Wong HC. Munchausen's syndrome presenting as prevarication anaphylaxis. Can J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999; 4:299–300.

3. Patterson R, Schatz M. Factitious allergic emergencies: anaphylaxis and laryngeal "edema". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1975; 56:152–159.

4. Selner JC, Staudenmayer H, Koepke JW, Harvey R, Christopher K. Vocal cord dysfunction: the importance of psychologic factors and provocation challenge testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1987; 79:726–733.

5. Choy AC, Patterson R, Patterson DR, Grammer LC, Greenberger PA, McGrath KG, Harris KE. Undifferentiated somatoform idiopathic anaphylaxis: nonorganic symptoms mimicking idiopathic anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995; 96:893–900.

6. Patterson R, Schatz M, Horton M. Munchausen's stridor: non-organic laryngeal obstruction. Clin Allergy. 1974; 4:307–310.

7. Patterson R, Greenberger PA, Orfan NA, Stoloff RS. Idiopathic anaphylaxis: diagnostic variants and the problem of nonorganic disease. Allergy Proc. 1992; 13:133–137.

8. Gimenez LM, Zafra H. Vocal cord dysfunction: an update. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011; 106:267–274.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download