Abstract

The use of topical anesthesia to perform intradermal tests (IDTs) for drug allergy diagnosis was never investigated. We aimed to determine the effects of a topical anesthetic patch containing prilocaine-lidocaine on wheal size of IDT with drugs. Patients who had positive IDT as part of their investigation process of suspected drug hypersensitivity were selected. IDT were performed according to guidelines. Anesthetic patch (AP) was placed and the same prior positive IDT, as well as positive histamine skin prick test (SPT) and negative (saline IDT) controls, were performed in the anesthetized area. Patients with negative IDT were also included to check for false positives with AP. Increase in wheals after 20 minutes both with and without AP was recorded and compared. 45 IDT were performed (36 patients), of which 37 have been previously positive (14 antibiotics, 10 general anesthetics, 6 non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, 3 iodinated contrasts, 3 anti-Hi-histamines and 1 ranitidine). Mean histamine SPT size without the AP was 4.7 mm [95%CI (4.4-5.1]), and 4.6 mm [95%CI(4.2-5.0)] with anesthesia. Mean wheal increase in IDT for drugs without the anesthesia was 4.5 mm [95%CI(3.3-5.7)] and with anesthesia was 4.3 mm [95%CI(2.8-5.8)]. No statistical significant differences were observed between skin tests with or without AP for histamine SPT (P=0.089), IDT with saline (P=0.750), and IDT with drugs (P=0.995). None of the patients with negative IDT showed positivity with the AP, or vice-versa. The use of an AP containing prilocaine-lidocaine does not interfere with IDT to diagnose drug allergy, and no false positive tests were found.

Some adverse reactions to drugs are allergic in its nature, leading to a particularly challenging diagnosis. Many doctors rely on the clinical history, but it is often not possible to disclose the cause, since different drugs are frequently taken simultaneously and the clinical picture of drug hypersensitivity can be very heterogeneous.1 Therefore, an attempt to prove the relationship between drug intake and symptoms and to clarify the underlying pathomechanism of the reaction should always be carried out. Convenient and reliable testing is needed in order to support sensitization to the suspected drug, as it might reduce unnecessary drug avoidance due to the concern of an allergic reaction. The diagnostic gold standard procedure is the controlled re-exposure with the suspected drug, but its application is often limited by the concern of severe reactions.

Skin prick tests (SPTs) and intradermal tests (IDTs) are widely used to evaluate sensitization and may provide insights concerning the underlying immunologic mechanism.2,3,4,5 For instance, in immediate β-lactam drug allergy, an IgE-mediated reaction can be demonstrated by a positive SPT and/or IDT after 20 minutes.6,7 By contrast, non-immediate reactions to β-lactams, presenting cutaneous symptoms and signs occurring more than one hour after last drug intake, are often T-cell mediated and a positive late-reading of an intradermal test could be found after several hours or days.8 Therefore, IDT are used to study both immediate and non-immediate reactions. However, IDT are painful, which often precludes their use, especially in young children.1

For many years, medicine has evolved and attention has been focused on prevention of medically induced pain. Thus, diagnostic or therapeutic acts, such as venous punctures, lumbar punctures, radial artery cannulation and vaccination are often preceded, both in children and adults, by topic anesthetic application of EMLA® (Eutectic Mixture of Local Anesthetics) cream, containing lidocaine and prilocaine (AstraZeneca Laboratories, Rueil-Malmaison, France).9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19

The use of a topical anesthetic cream containing lidocaine-prilocaine also significantly reduces pain associated with allergy skin tests, as proven in previous studies.20,21,22 However, because lidocaine-prilocaine acts on the skin, changing basal skin perfusion,23 concerns have been raised that the use of EMLA® for alleviating pain caused by IDT could interfere with the wheal and flare response by modifying the number of recruited sensitized cells.24 Therefore, its use on IDT for drug allergy diagnosis was left aside. Nevertheless, this practice has been relying solely on assumptions as it was never investigated. New tests are now available to diagnose drug allergy,25,26,27 but they cannot be used interchangeably with skin testing. They also cause pain, as most of them imply blood collection. So, demonstrating that the use of topical anesthesia does not interfere with the results of IDT would have major practical implications for the diagnosis of drug allergy, as it would allow testing more patients, including children, without the side-effect of pain.

We aimed to determine the effects of a topical anesthetic patch containing lidocaine-prilocaine on wheal response to IDT with drugs in patients with suspected drug allergy.

This is a cross-sectional open-label case-control study carried out in the Allergy Department of a University Hospital, from May 2010 to May 2012. Patients who performed skin drug allergy testing due to suspected immediate drug hypersensitivity reactions were enrolled. Those who presented positive results to IDT were invited to participate in the study. Written information about the study was provided, informed consent was signed and clinical data were collected. Patients worked as controls of themselves and IDT test was performed in the other arm, after EMLA® patch had been applied and removed. The following were considered exclusion criteria: delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions; pregnancy or lactation; prior hypersensitivity reactions to local anesthetics; prior serious reactions during IDT; patients with methemoglobinemia; patients who require methemoglobin-inducing agents; patients with known hypersensitivity reactions to non-medical components of EMLA® patch (carboxypolymethylene, polyoxyethylene hydrogenated castor oil, sodium hydroxide and acrylate); and those taking any systemic medication that could possibly interfere with the study.1

Patients with history of immediate drug hypersensitivity reactions and negative IDT were also included to evaluate the possible occurrence of false positives.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects and all patients signed an informed consent.

EMLA-patch® contains a mixture of lidocaine (25 mg/g) and prilocaine (25 mg/g) bases, mixed in a thickener (carboxypolymethylene), an emulsifier (polyoxythiylene fatty acids esters) and water. Prior to injection, the anesthetic patch was applied for 1 hour on the volar surface of the forearm, according to manufacturer's recommendations.

IDT were performed according to EAACI's guidelines.1 Twenty minutes after injection, the reaction was considered positive if the size increased in diameter by at least 3 mm, associated with a flare.1 The mean diameter was calculated by measuring the largest and the smallest diameters at right angles to each other with a millimeter ruler. Afterwards, the mean of both diameters was calculated.1 Case and control tests were performed simultaneously, e.g. if the patient tested positive in the arm without EMLA® patch, it (EMLA® patch) was immediately placed in the other arm. The same exact procedure was repeated on the anesthetized area, after removing EMLA® patch.

The positive control was performed by skin prick testing technique using histamine (10 mg/mL, Leti® Company, Madrid, Spain) and the same procedure was performed in the anesthetized area after removing EMLA® patch. Intradermal injection of negative control (saline) was also performed.

Adverse effects were recorded including pallor, erythema, mild swelling or contact dermatitis.

All data analyses were performed using SPSS statistical package 20.0 for Windows (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables are presented as mean (95% confidence interval, CI), except in the case of age in which the standard deviation is presented. Log-transformation was performed for skewed distributions.

The sample size was calculated assuming a difference in the intradermal test wheal size measurements between cases and control of 0.5 mm and a standard deviation of 1 mm assessed by paired sample t-test with a power (1-β) of 80%, a total target of 33 tests would be needed for a level of significance of 0.05.

For SPT with histamine and IDT with saline, the final wheal (at the end of 15 and 20 minutes, respectively) was used. For IDT with drugs, the increase of the wheal after 20 minutes was used and calculated as follows: average diameter of last wheal minus average diameter of the initial wheal. Paired samples t-student test, or Wilcoxon test, for non-normally distributed variables, were applied to compare data with and without the EMLA® patch (P<0.05).

Thirty-six Caucasian patients (27 females, mean age, 46±18 years), of which 2 children, were included. 45 IDT were performed, with and without EMLA, with different classes of drugs.

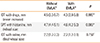

Thirty-seven IDT had been previously positive and were repeated in the same patient's other arm anesthetized with EMLA®: 14 with antibiotics (cefazolin; n=5, amoxicillin; n=3, penicillin minor determinants mixture; n=1, clarithromycin; n=1, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; n=1, ciprofloxacin; n=1, meropenem; n=1, sulfametoxazol-trimetoprim; n=1), 10 with general anesthetics (midazolam; n=3, rocuronium; n=2, cisatracurium; n=2, atracurium; n=1, atropine; n=1, ketamine; n=1), 6 with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (diclofenac; n=5, metamizole; n=1), 3 with iodinated contrasts (ioversol, iopromide and iomeprol), 3 with anti-H1-histamines (hidroxizine; n=2, and clemastine) and 1 with ranitidine. No differences were obtained for skin tests with or without the anesthetic patch for IDT with drugs, saline controls or SPT with histamine (Table 1). In the analysis of each drug family, the increase in the mean size of wheals with and without EMLA was similar (Table 2), except for ranitidine. With this drug, although it was tested in only one patient, we have observed a twice fold increase in the mean wheal size with EMLA®. None of the patients presented a flare reaction larger than the wheal size. No reduction in the flare area for histamine was observed with EMLA®. At no time was the flare or the wheal obliterated.

None of the 8 control patients with negative IDT (1 with pyridoxine, and the remaining with antibiotics: amoxicillin; n=2, ampicillin; n=2, minor determinants mixture; n=1, penicillin n=1, isoniazid; n=1) showed positivity in IDT performed in the anaesthetized area.

No immediate or delayed side-effects were reported.

Almost all patients stated a decrease in pain, although no objective assessment scale was used.

Our study shows that IDT readings are not affected by the use of an anesthetic patch containing lidocaine-prilocaine, despite the theoretical speculation of a possible negative role on the recruitment of sensitized lymphocytes.24

The pain associated with allergy skin tests significantly decreases with the use of topical anesthetic, as clearly demonstrated in previous studies.20,21,22 However, in those studies, IDT were performed with aeroallergens20 or only with histamine and saline controls.21,22 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that the effects of EMLA® on the readings of IDT with drugs have been investigated.

Our results have demonstrated that the use of a topical anesthetic patch does not influence the results negatively; no false positive or false negative test results were found.

There are some limitations to be considered. As this was a real-life study, only patients referenced to our Drug Allergy Unit were included; therefore, the drugs used and the number of children included were consecutive and not selected. Only 2 children were tested, and therefore it is not possible to conclude from our data that the readings of IDT with drugs are not affected by EMLA® in children; however, that would not be expectable since differences on adults and children's skin responses have never been reported before.

Besides, a comparison with other type of topical anesthetic formulations, namely topical cream, was not performed. Hence, results cannot be generalized since the efficacy might be different with this type of topical application. A visual analogue scale could have been used to measure pain associated with IDT before and after the anesthetic patch. However, this was not the aim of our study. For that purpose, the study should have been blind, but that has already been reported in previous literature.20,21,22 We did not include SPT as part of our study, since they are much less painful than IDT and therefore the use of an expensive anesthetic patch is less likely to be necessary.

Our study also presents several strengths, namely: this was the first time that the influence of the use of EMLA® in the results of IDT with drugs was evaluated; we have used an appropriate sample size to determine the effects of our hypothesis; we have applied a patch that delivered a standardized amount of anesthetic to each patient; and the IDT were performed with and without EMLA® in the same patients in order to enhance the control for confounding factors. We have only included Caucasian patients not to bias the results, since it has been previously reported that African-American have later onset and reduced magnitude of anesthesia effects of EMLA®.28 Due to the real life nature of this study, different classes of drugs were tested; although it did not include a sufficient number of subjects for all drug classes and, moreover, it was not possible to test all drug classes, it provided important information. It does not seem from our data that results are dependent on the type of drug used to perform IDT. Nonetheless, larger, multi-center, prospective studies are needed to verify this hypothesis, extend these results to other classes of drugs and also to explore the possibility of false-negative tests occurrence with EMLA®.

Previous studies addressing this issue presented contradictory data regarding the wheal and flare effects, although showing agreement in what concerns the pain decreasing outcome. The first placebo-controlled study showed that EMLA® did not decrease the mean wheal and flare areas after saline and did not decrease the mean wheal area after histamine; nevertheless, for the flare area, a significant decrease was observed in those with EMLA® application compared to placebo for the injection of histamine 0.1 mg/mL.22 It should be noted, however, that this effect was only evidenced with this concentration and did not occur with histamine at 10 mg/mL, which is the recommended concentration for allergy testing. Moreover, this study only included 12 healthy volunteers, so no allergens were tested in this sample. Although with these limitations, that study definitely marked the trajectory of guidelines in the field of allergy testing. Even when later studies, with larger samples and including allergen testing, showed no differences on the wheal size responses with EMLA® compared to placebo,20,21 the non-performance of the skin allergy diagnostic procedures was still advocated. In 1994, Wolf et al. performed the largest study until now, which included 40 subjects aged 1 to 9 and proved that no significant differences occur in wheal or flare reactions between anaesthetized and untreated skin.21 Antigens were used only in 10 patients, and the remaining patients only had histamine and saline tests performed. Complete anesthesia was obtained in 90% of cases.21 Later, in 1997, Sicherer et al.20 included 20 adult volunteers with a history of positive tests to at least one inhalant allergen. Both SPTs (n=20) and IDTs (n=15 with allergens and n=19 with histamine) were performed and results were evaluated at 15 minutes. The wheal sizes for allergen prick tests, allergen IDT and histamine IDT were identical when comparing placebo to EMLA-treated skin. Flare responses were reduced on the actively treated skin for allergen prick tests (P<0.001) and histamine IDT (P<0.0001), but not for IDT with allergens (P=0.058); however, while the erythema was variably reduced on the EMLA-treated side, the largest reductions occurred for tests in which the flare was over 10 mm larger than the wheal. In addition, there was complete suppression of the flare response in 9 tests, all on the EMLA treated skin. These results are contradictory to our findings and to those reported by Wolf et al.21 as both studies evidenced no effect on flare responses. In Wolf's et al. study, the flare responses were generally less than 2 cm in diameter,21 and this discrepancy in reaction sizes for Sicherer's et al. study20 could explain the difference in the effects on flares responses, since EMLA® has been shown to reduce the flare in an area beyond 2 cm from the injection site of histamine using Doppler velocimetry.29 From a practical point of view, since it occurred only in tests whose flare was very large, a diminished reaction would not compromise the correct diagnosis. It would only be of concern if it occurred in patients having small flare reactions, who could be wrongly diagnosed. In fact, in Sicherer's et al. study, the few subjects with flares whose radius was less than 5mm had modest or no reduction in the flare by the EMLA®.20

It has been suggested that the effects of EMLA® on the flare responses preclude its use for diagnostic skin testing. Our study re-opens this discussion. Since the wheal responses were not affected in ours or any of the previously published studies,20,21,29,30,31 and being the wheal more likely to be used as criteria for positivity, it seems that the topical anesthesia can be reliably used. Therefore, it might be a suitable method for implementation, as long as the considered criterion for diagnosis is the wheal increase. It enables allergists to perform this diagnostic procedure in very young children in the work up diagnosis of drug allergy and will improve patient's comfort. The cost of EMLA® and the 1-hour waiting must be considered for practical and economical purposes before routinely application of this procedure. Further studies are needed with larger population samples, with concomitant quantification of cost, and focusing specially in the younger sub groups that most benefit from it.

The use of an EMLA® patch did not affect the wheal size of skin drug allergy testing in a wide sample of drugs tested in our study. The use of topical anesthesia is therefore a valuable option, particularly in children or patients more sensitive to pain. Further studies are needed with larger population samples, with concomitant quantification of cost and focusing specially in the younger sub groups that most benefit from this treatment. The procedure seems safe and did not interfere in the diagnostic evaluation.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Effect of EMLA® on wheal responses for SPT with histamine and IDT with drugs and saline control (n=37 IDT)

Table 2

Effect of EMLA® on wheal size responses of positive IDT with drugs (n=37)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To Dr Eunice Castro and Dr Carmen Botelho for their valuable opinions and scientific contribute.

References

1. Brockow K, Romano A, Blanca M, Ring J, Pichler W, Demoly P. General considerations for skin test procedures in the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity. Allergy. 2002; 57:45–51.

2. Barbaud A, Reichert-Penetrat S, Tréchot P, Jacquin-Petit MA, Ehlinger A, Noirez V, Faure GC, Schmutz JL, Béné MC. The use of skin testing in the investigation of cutaneous adverse drug reactions. Br J Dermatol. 1998; 139:49–58.

3. Calkin JM, Maibach HI. Delayed hypersensitivity drug reactions diagnosed by patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 1993; 29:223–233.

4. Bruynzeel DP, Maibach HI. Patch testing in systemic drug eruptions. Clin Dermatol. 1997; 15:479–484.

5. Osawa J, Naito S, Aihara M, Kitamura K, Ikezawa Z, Nakajima H. Evaluation of skin test reactions in patients with non-immediate type drug eruptions. J Dermatol. 1990; 17:235–239.

6. Blanca M, Vega JM, Garcia J, Carmona MJ, Terados S, Avila MJ, Miranda A, Juarez C. Allergy to penicillin with good tolerance to other penicillins; study of the incidence in subjects allergic to beta-lactams. Clin Exp Allergy. 1990; 20:475–481.

7. Romano A, Di Fonso M, Papa G, Pietrantonio F, Federico F, Fabrizi G, Venuti A. Evaluation of adverse cutaneous reactions to aminopenicillins with emphasis on those manifested by maculopapular rashes. Allergy. 1995; 50:113–118.

8. Romano A, Quaratino D, Di Fonso M, Papa G, Venuti A, Gasbarrini G. A diagnostic protocol for evaluating nonimmediate reactions to aminopenicillins. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999; 103:1186–1190.

9. Juhlin L, Evers H, Broberg F. A lidocaine-prilocaine cream for superficial skin surgery and painful lesions. Acta Derm Venereol. 1980; 60:544–546.

10. Rosdahl I, Edmar B, Gisslén H, Nordin P, Lillieborg S. Curettage of molluscum contagiosum in children: analgesia by topical application of a lidocaine/prilocaine cream (EMLA). Acta Derm Venereol. 1988; 68:149–153.

11. Halperin DL, Koren G, Attias D, Pellegrini E, Greenberg ML, Wyss M. Topical skin anesthesia for venous, subcutaneous drug reservoir and lumbar punctures in children. Pediatrics. 1989; 84:281–284.

12. Smith M, Gray BM, Ingram S, Jewkes DA. Double-blind comparison of topical lignocaine-prilocaine cream (EMLA) and lignocaine infiltration for arterial cannulation in adults. Br J Anaesth. 1990; 65:240–242.

13. Taddio A, Nulman I, Reid E, Shaw J, Koren G. Effect of lidocaineprilocaine cream (EMLA®) on pain of intramuscular Fluzone® injection. Can J Hosp Pharm. 1992; 45:227–230.

14. Taddio A, Robieux I, Koren G. Effect of lidocaine-prilocaine cream on pain from subcutaneous injection. Clin Pharm. 1992; 11:347–349.

15. Taddio A, Nulman I, Goldbach M, Ipp M, Koren G. Use of lidocaine-prilocaine cream for vaccination pain in infants. J Pediatr. 1994; 124:643–648.

16. Taddio A, Stevens B, Craig K, Rastogi P, Ben-David S, Shennan A, Mulligan P, Koren G. Efficacy and safety of lidocaine-prilocaine cream for pain during circumcision. N Engl J Med. 1997; 336:1197–1201.

17. Valenzuela RC, Rosen DA. Topical lidocaine-prilocaine cream (EMLA) for thoracostomy tube removal. Anesth Analg. 1999; 88:1107–1108.

18. Halperin SA, McGrath P, Smith B, Houston T. Lidocaine-prilocaine patch decreases the pain associated with the subcutaneous administration of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine but does not adversely affect the antibody response. J Pediatr. 2000; 136:789–794.

19. Buckley MM, Benfield P. Eutectic lidocaine/prilocaine cream. A review of the topical anaesthetic/analgesic efficacy of a eutectic mixture of local anaesthetics (EMLA). Drugs. 1993; 46:126–151.

20. Sicherer SH, Eggleston PA. EMLA cream for pain reduction in diagnostic allergy skin testing: effects on wheal and flare responses. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1997; 78:64–68.

21. Wolf SI, Shier JM, Lampl KL, Schwartz R. EMLA cream for painless skin testing: a preliminary report. Ann Allergy. 1994; 73:40–42.

22. Simons FE, Gillespie CA, Simons KJ. Local anaesthetic creams and intradermal skin tests. Lancet. 1992; 339:1351–1352.

23. Arildsson M, Asker CL, Salerud EG, Strömberg T. Skin capillary appearance and skin microvascular perfusion due to topical application of analgesia cream. Microvasc Res. 2000; 59:14–23.

24. Dubus JC, Mely L, Lanteaume A. Use of lidocaine-prilocaine patch for the mantoux test: Influence on pain and reading. Int J Pharm. 2006; 327:78–80.

25. de Weck AL, Sanz ML. Cellular allergen stimulation test (CAST) 2003, a review. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2004; 14:253–273.

26. Sanz ML, Gamboa PM, De Weck AL. Cellular tests in the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity. Curr Pharm Des. 2008; 14:2803–2808.

27. Sanz ML, Maselli JP, Gamboa PM, Oehling A, Diéguez I, de Weck AL. Flow cytometric basophil activation test: a review. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2002; 12:143–154.

28. Hymes JA, Spraker MK. Racial differences in the effectiveness of a topically applied mixture of local anesthetics. Reg Anesth. 1986; 11:11–13.

29. Harper EI, Beck JS, Spence VA. Effect of topically applied local anaesthesia on histamine flare in man measured by laser Doppler velocimetry. Agents Actions. 1989; 28:192–197.

30. Bjerring P, Arendt-Nielsen L. A quantitative comparison of the effect of local analgesics on argon laser induced cutaneous pain and on histamine induced wheal, flare and itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 1990; 70:126–131.

31. Pipkorn U, Andersson M. Topical dermal anaesthesia inhibits the flare but not the weal response to allergen and histamine in the skin-prick test. Clin Allergy. 1987; 17:307–311.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download