Abstract

Purpose

Multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS) is a clinical syndrome representing multi-organ and psychological symptoms caused by chronic exposure to various chemicals in low concentrations. We evaluated the prevalence and related factors of MCS targeting Korean adults using the Quick Environmental Exposure and Sensitivity Inventory (QEESI©).

Methods

A total of 446 participants were recruited from Severance Hospital. Participants underwent a questionnaire interview including questions on sociodemographic factors, occupational and environmental factors, allergic diseases, and the QEESI©. Among them, 379 participants completed the questionnaire and the QEESI©. According to the QEESI© interpretation results, participants were divided into very suggestive (VS) group and less suggestive (LS) group.

Results

The estimated prevalence of MCS was higher in allergic patients than non-allergic participants (19.7% and 11.3%, respectively, P=0.04). In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, ages of 30-39 (OR, 2.94; 95% CI, 1.25-6.95) and those of 40-49 (OR, 2.51; 95% CI, 1.02-6.21) were significantly related to MCS compared to those aged less than 30 years. Female sex (OR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.11-4.18), experience of dwelling in a new house (OR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.04-4.03), and atopic dermatitis (OR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.04-3.69) were also significantly related to MCS. However, only age of 30-39 in the allergic group was significant in the stratified analysis.

Conclusions

The estimated prevalence of MCS was higher among allergic patients than non-allergic participants. People with experience of dwelling in a new house and atopic dermatitis were more at risk of being intolerant to chemicals. Further studies to provide the nationally representative prevalence data and clarify risk factors and mechanisms of MCS are required.

Multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS) is a clinical syndrome representing multi-organ and psychological symptoms caused by chronic exposure to various chemicals in low concentrations.1,2 Idiopathic environmental intolerance (IEI) is another term for MCS as defined by the World Health Organization in 1996.3 Although many patients suffer from MCS/IEI worldwide, many clinicians do not accept MCS/IEI as a well clarified disease condition because clinical manifestations of MCS/IEI are different from the direct toxicities of exposed chemicals.4

In the development of MCS/IEI, initial exposure to high concentration of culprit chemical is important but not crucial, and not all initial symptoms of MCS/IEI are related to high concentration chemical exposure.5,6 Some possible mechanisms have been suggested for MCS/IEI development and propagation. Toxicant induced loss of tolerance theory explains that many different kinds of chemicals can be responsible for exacerbation of symptoms even if initial chemical exposures cause loss of tolerance.7 Psychiatric mechanisms may be involved in some patients who have complaints of somatoform symptoms like chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia.8 Recent research has suggested olfactory-limbic mechanisms such as hypersensitivity of olfactory epithelium caused by chemical exposure influences on hormonal and emotional control of the hypothalamus.9

Although there are no international diagnostic criteria for MCS/IEI, repetitive symptoms after re-challenge, diminished symptoms after de-challenge of chemical exposure and simultaneous multi-organ symptoms are frequently used for diagnosis of MCS/IEI.10 Therefore, Miller and Prihoda developed the environment exposure sensitivity inventory (EESI) and its shortened form quick EESI (QEESI©) to evaluate chemical exposure in daily life and sensitivity to those chemicals.11,12 The QEESI© is well validated and has been used in many countries to evaluate the possibility of MCS/IEI.13,14 Recently, the Korean version of the QEESI© was validated for use in predicting the possibility of MCS/IEI in Korean people.15 Although most people are exposed to low concentration of various chemicals in their daily lives, population-based studies on the prevalence and/or possible influencing factors of MCS/IEI are still lacking in Korea.

In this study, we evaluated the prevalence of MCS/IEI in the Korean population using the Korean version of the QEESI© to screen for the highly sensitive people and suggested the probable risk factors of development of MCS/IEI in Korea.

Participants were recruited from July first to August 31st, 2012 at Severance Hospital. The Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Health System approved this study (IRB no. 4-2012-0328) and informed consent was obtained from all participants. A total 446 participants underwent systematic questionnaire interview. The questionnaire contained questions on sociodemographic variables (including age, sex, and smoking status), occupational and environmental factors and existence of allergic disease.

Occupational and environmental factors included environmental tobacco smoke exposure, experience of dwelling in a new house, household chemical use and occupational exposure to chemicals. Questions from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) questionnaire were adopted to assess asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis.16 Participants were defined as allergic participants if they answered at least one of three questions (asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis questions from ISAAC) positively. Participants were also administered the Korean version of the QEESI©.15

Among all participants, 67 participants were excluded due to missing information in the questionnaire (n=55) and the QEESI© (n=12). Finally, the data of 379 participants were analyzed.

The QEESI© is a validated, self-administered instrument for evaluating multiple chemical intolerance. It consists of four subscales: symptom severity, chemical intolerance, other intolerance, and life impact. Total score for each scale is 100, and each scale can be divided into low, medium, and high. The cut-off points are 20 and 40 for symptom severity and chemical intolerance, 12 and 25 for other intolerance, and 12 and 24 for life impact. According to the QEESI© interpretation results, participants were divided into four groups: not suggestive group (symptom severity score <40 and chemical intolerance score <40; symptom severity score ≥40, chemical score <40, and masking score <4), problematic group (symptom severity score <40 and chemical intolerance score ≥40), somewhat suggestive group (symptom severity score ≥40, chemical intolerance score <40, and masking score ≥4), and very suggestive group (symptom severity score ≥40 and chemical intolerance score ≥40).11 In the analysis, the three groups other than the very suggestive (VS) group were merged into one group (less suggestive group, LS group).

In order to compare the characteristics of the LS group and VS group, Student's t-tests and chi-square tests were conducted for continuous variables and categorized variables. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were estimated by multivariate logistic regression analysis defining the suggestive level of MCS/IEI as the dependent variable. Participants were then stratified into allergic group and non-allergic group, and ORs and 95% CIs were calculated for each group.

All statistical tests were 2-tailed, and P values of less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted with the SAS software package version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

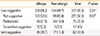

The general characteristics of study participants are shown in Table 1. Sixty two participants were classified into the VS group and 317 into the LS group. Among them, 228 participants (60.2%) had at least one allergic disease. The mean age of total participants and in each group was 39.8±10.1 (total), 38.9±9.5 (VS group), and 38.1±11.5 (LS group). Females showed a higher prevalence of MCS/IEI than males (P=0.03). The proportion of non-smokers, asthma patients, allergic rhinitis patients, and atopic dermatitis patients were higher in the VS group. However, only the proportion of atopic dermatitis patients showed a significant difference (P=0.02). In the stratified analysis, there were no significant differences in the proportion of sex, smokers in both the allergic and non-allergic group and in the proportion of asthma patients, allergic rhinitis patients, and atopic dermatitis patients in the allergic group.

Many of participants had been exposed to environmental tobacco smoke, lived in a new house, and had been exposed to chemicals at work. Participants who sometimes used household chemicals were included in the VS group more likely. However, only the experience of dwelling in a new house showed significant difference (Table 2). In the stratified analysis, there was no significant difference to exposures between LS and VS group.

The proportion of participants classified into the VS group was 16.4% in this study, and was higher in allergic patients than in non-allergic participants (19.7% and 11.3%, Table 3). The difference in suggestive degree between allergic and non-allergic participants was not statistically significant in the four-group comparison (P=0.07). However, the difference became significant when the not suggestive, the problematic, and the somewhat suggestive group were merged into less suggestive group (P=0.04). The mean scores of the QEESI© subscales: symptom severity, chemical intolerance, other intolerance, and life impact showed significant differences between the allergic and non-allergic group, however, none of them exceeded the high cut-off level (Table 4). The proportion of participants classified as 'high' was also higher in the allergic group in all subscales (symptom severity: 26.3% in allergic, 14.6% in non-allergic, P<0.01, chemical intolerance: 41.2% in allergic, 31.1% in non-allergic, P=0.06, other intolerance: 33.5% in allergic, 18.1% in non-allergic, P<0.01, and life impact: 34.2% in allergic, 20.7% in non-allergic, P<0.01).

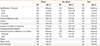

In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, participants in their fourth and fifth decade and females were more likely to be included in the VS group. The ORs for these groups were 2.94 (95% CI 1.25-6.95), 2.51 (1.02-6.21), and 2.16 (1.11-4.18), respectively. Participants with experience of dwelling in a new house and atopic dermatitis showed ORs of 2.05 (1.04-4.03) and 1.95 (1.04-3.69), respectively. In the allergic group, female sex, experience of dwelling in a new house, and atopic dermatitis became non-significant when stratified; only age of 30-39 remained significant (3.14, 1.16-8.45) (Table 5).

MCS/IEI is an emerging medical issue worldwide. However, diagnostic and therapeutic measures for MCS/IEI are still controversial.17 Moreover, its exact prevalence is unclear. To the authors' knowledge, this is the first study to report the prevalence and related risk factors of MCS/IEI targeting allergic and non-allergic Korean adults using the QEESI©. Participants were recruited from Severance Hospital, and regarded as having MCS/IEI when classified into the VS group. In Korea, studies reporting case or prevalence of MCS/IEI are scarce. There is a report of MCS/IEI in farmers exposed to pesticides and one study reported the prevalence of MCS/IEI using the QEESI©.15,18 The estimated prevalence of MCS/IEI was 16.4% in the present study. There was a difference in prevalence according to existence of allergic disease; prevalence in allergic patients was 19.7% and 11.3% in non-allergic participants. Age, female sex, experience of dwelling in a new house, and atopic dermatitis were found to be significantly related factors.

A number of other studies used the QEESI©. Prevalence was 20.3% in a study conducted in clinics in the U.S. and 20.3% and 21.7% in Korea if the same diagnostic criteria used in this study are applied.15,19 In studies using other diagnostic criteria, prevalence of 15.9%, 12.5%, and 11.2% in the U.S. were reported, and a prevalence of 9% was reported in Germany.20,21,22,23 In our study, the prevalence in total participants was 16.4%, and when participants are divided by recruiting site, prevalence was 20.8% in allergy clinic patients and 12.8% in health examination center visitors. The prevalence in total participants was similar to the results from the U.S., even though different diagnostic criteria were used, and the prevalence in clinic patients was also similar to that of U.S. clinic patients. However, other studies have shown different prevalence. The study conducted in Germany showed relatively lower prevalence due to the application of stricter diagnostic criteria, and the other Korean study showed relatively higher prevalence, most likely due to the demographic differences of subjects in this study.

In previous studies exploring the initiating factors of MCS/IEI, frequently reported factors or agents were solvents, cleaners, indoor air contaminants, pesticides, and job-related chemical exposures.12,24,25 In this study, only the experience of dwelling in a new house was significantly related. Exposure to indoor air contaminants in a newly built home or school was also the most common onset factor in a Japanese study.25 This may be because people living in newly built houses are often exposed to various kinds of volatile organic compounds.26 However, the relationship between MCS/IEI and job-related chemical exposure was not significant. One possible explanation is the non-differential misclassification of job-related chemical exposure which tends to bias the associations towards the null. Another possible explanation is that because the analysis was conducted with current job or job-related exposure, effects from former jobs or exposures could not be assessed. The relationship between MCS/IEI and pesticide use could not be assessed because most participants lived in urban areas, and only one participant reported pesticide use.

MCS/IEI and allergic diseases are known to be related to each other,27 and associations have been reported in previous studies.19,25,28 In this study, the prevalence between the allergic and non-allergic groups was also different, and the average scores of the QEESI© subscales also showed differences, except for the masking index. One possible explanation is that the perception of chemical exposure of allergic patients was higher than that of non-allergic participants. In general, symptoms of allergic airway disease could be aggravated when patients are exposed to cold and dry air, air pollutants, and environmental chemicals. Volatile organic compounds and phthalates are well known chemical irritants in asthmatics.29,30 However, unlike other previous studies that reported asthma and rhinitis as comorbid diagnoses,31,32 only atopic dermatitis was significantly related to MCS/IEI in this study.

This study has several limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional design, there could be recall bias regarding information on chemical exposures at work or home. Second, because information about participants in this study was only obtained via questionnaire, there could be some false positives or false negatives. In order to reduce this risk, validated questionnaires were used and people with acute disease or severe symptoms were not recruited. Third, this study had limited statistical power due to the small number of participants. Therefore, some differences did not reach statistical significance in stratified analysis. Lastly, this is an epidemiologic study; thereby has difficulty in explaining mechanisms of development of MCS/IEI.

MCS/IEI patients can frequently present multi-organ and psychological symptoms. Moreover, common somatic symptoms they complain include central nervous system symptoms (i.e., headache, fatigue, and cognitive deficit), musculoskeletal symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, and dermatologic symptoms.1,2,33 Although there are no universal diagnostic criteria or tests for MCS/IEI, patients could be referred to allergists for evaluation of culprit agents. Therefore, it is important to suspect MCS/IEI in a patient with MCS/IEI features described above rather than ignore patients' complaints in an allergy clinic.

In conclusion, the estimated prevalence of MCS/IEI in present study was 16.4%, and was higher among allergic patients than non-allergic participants (19.5%, 11.3%, respectively). People with experience of dwelling in a new house and atopic dermatitis are more at risk of being intolerant to chemicals. Further studies to provide the nationally representative prevalence data and clarify risk factors, mechanisms, and the relationship between allergic disease and MCS/IEI are required.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

General characteristics of study participants

Table 2

Environmental chemical exposures of study participants

Table 3

Distribution of participants by suggestive degree group

Table 4

Mean scores of the QEESI© subscales

Table 5

Odd ratios for very suggestive of MCS/IEI in relation to risk factors

References

1. Sparks PJ, Daniell W, Black DW, Kipen HM, Altman LC, Simon GE, Terr AI. Multiple chemical sensitivity syndrome: a clinical perspective. II. Evaluation, diagnostic testing, treatment, and social considerations. J Occup Med. 1994; 36:731–737.

2. Graveling RA, Pilkington A, George JP, Butler MP, Tannahill SN. A review of multiple chemical sensitivity. Occup Environ Med. 1999; 56:73–85.

3. Conclusions and recommendations of a workshop on Multiple Chemical Sensitivities (MCS): February 21-23, 1996, Berlin, Germany. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 1996; 24:S188–S189.

4. Gibson PR, Lindberg A. Physicians' perceptions and practices regarding patient reports of multiple chemical sensitivity. ISRN Nurs. 2011; 2011:838930. doi: 10.5402/2011.838930.

5. Watanabe M, Tonori H, Aizawa Y. Multiple chemical sensitivity and idiopathic environmental intolerance (part one). Environ Health Prev Med. 2003; 7:264–272.

6. Watanabe M, Tonori H, Aizawa Y. Multiple chemical sensitivity and idiopathic environmental intolerance (part two). Environ Health Prev Med. 2003; 7:273–282.

7. Sparks PJ, Daniell W, Black DW, Kipen HM, Altman LC, Simon GE, Terr AI. Multiple chemical sensitivity syndrome: a clinical perspective. I. Case definition, theories of pathogenesis, and research needs. J Occup Med. 1994; 36:718–730.

8. Pall ML. Common etiology of posttraumatic stress disorder, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and multiple chemical sensitivity via elevated nitric oxide/peroxynitrite. Med Hypotheses. 2001; 57:139–145.

9. Orriols R, Costa R, Cuberas G, Jacas C, Castell J, Sunyer J. Brain dysfunction in multiple chemical sensitivity. J Neurol Sci. 2009; 287:72–78.

10. Multiple chemical sensitivity: a 1999 consensus. Arch Environ Health. 1999; 54:147–149.

11. Miller CS, Prihoda TJ. The Environmental Exposure and Sensitivity Inventory (EESI): a standardized approach for measuring chemical intolerances for research and clinical applications. Toxicol Ind Health. 1999; 15:370–385.

12. Miller CS, Prihoda TJ. A controlled comparison of symptoms and chemical intolerances reported by Gulf War veterans, implant recipients and persons with multiple chemical sensitivity. Toxicol Ind Health. 1999; 15:386–397.

13. Nordin S, Andersson L. Evaluation of a Swedish version of the Quick Environmental Exposure and Sensitivity Inventory. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2010; 83:95–104.

14. Hojo S, Kumano H, Yoshino H, Kakuta K, Ishikawa S. Application of Quick Environment Exposure Sensitivity Inventory (QEESI) for Japanese population: study of reliability and validity of the questionnaire. Toxicol Ind Health. 2003; 19:41–49.

15. Jeon BH, Lee SH, Kim HA. A validation of the Korean version of QEESI(c) (The Quick Environmental Exposure and Sensitivity Inventory). Korean J Occup Environ Med. 2012; 24:96–114.

16. Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, Beasley R, Crane J, Martinez F, Mitchell EA, Pearce N, Sibbald B, Stewart AW, Strachan D, Weiland SK, Williams HC. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 1995; 8:483–491.

17. Hetherington L, Battershill J. Review of evidence for a toxicological mechanism of idiopathic environmental intolerance. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2013; 32:3–17.

18. Lee HS, Hong SY, Hong ZR, Gil HO, Yang JO, Lee EY, Han MJ, Jang NW, Hong SY. Pesticide-initiated idiopathic environmental intolerance in South Korean farmers. Inhal Toxicol. 2007; 19:577–585.

19. Katerndahl DA, Bell IR, Palmer RF, Miller CS. Chemical intolerance in primary care settings: prevalence, comorbidity, and outcomes. Ann Fam Med. 2012; 10:357–365.

20. Kreutzer R, Neutra RR, Lashuay N. Prevalence of people reporting sensitivities to chemicals in a population-based survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1999; 150:1–12.

21. Caress SM, Steinemann AC. Prevalence of multiple chemical sensitivities: a population-based study in the southeastern United States. Am J Public Health. 2004; 94:746–747.

22. Caress SM, Steinemann AC. A national population study of the prevalence of multiple chemical sensitivity. Arch Environ Health. 2004; 59:300–305.

23. Hausteiner C, Bornschein S, Hansen J, Zilker T, Förstl H. Self-reported chemical sensitivity in Germany: a population-based survey. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2005; 208:271–278.

24. Caress SM, Steinemann AC, Waddick C. Symptomatology and etiology of multiple chemical sensitivities in the southeastern United States. Arch Environ Health. 2002; 57:429–436.

25. Hojo S, Ishikawa S, Kumano H, Miyata M, Sakabe K. Clinical characteristics of physician-diagnosed patients with multiple chemical sensitivity in Japan. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2008; 211:682–689.

26. Shin SH, Jo WK. Volatile organic compound concentrations, emission rates, and source apportionment in newly-built apartments at pre-occupancy stage. Chemosphere. 2012; 89:569–578.

27. Meggs WJ. Mechanisms of allergy and chemical sensitivity. Toxicol Ind Health. 1999; 15:331–338.

28. Meggs WJ, Dunn KA, Bloch RM, Goodman PE, Davidoff AL. Prevalence and nature of allergy and chemical sensitivity in a general population. Arch Environ Health. 1996; 51:275–282.

29. Wieslander G, Norbäck D, Björnsson E, Janson C, Boman G. Asthma and the indoor environment: the significance of emission of formaldehyde and volatile organic compounds from newly painted indoor surfaces. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1997; 69:115–124.

30. Jaakkola JJ, Ieromnimon A, Jaakkola MS. Interior surface materials and asthma in adults: a population-based incident case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006; 164:742–749.

31. Bell IR, Schwartz GE, Peterson JM, Amend D. Self-reported illness from chemical odors in young adults without clinical syndromes or occupational exposures. Arch Environ Health. 1993; 48:6–13.

32. Baldwin CM, Bell IR. Increased cardiopulmonary disease risk in a community-based sample with chemical odor intolerance: implications for women's health and health-care utilization. Arch Environ Health. 1998; 53:347–353.

33. Lacour M, Zunder T, Schmidtke K, Vaith P, Scheidt C. Multiple chemical sensitivity syndrome (MCS)--suggestions for an extension of the U.S. MCS-case definition. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2005; 208:141–151.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download