Abstract

Purpose

Specific immunotherapy (SIT) is a suitable but uncommon treatment option for allergic rhinitis (AR) in China. The current understanding and attitude of Chinese ENT (ear, nose, and throat) specialists in regards to SIT is unclear. This study investigates current trends in the awareness and application status of SIT among Chinese ENT specialists.

Methods

We performed a nationwide, cross-sectional survey with a specially designed questionnaire given to 800 ENT specialists in China. A member of the trained research group conducted face-to-face interviews with each respondent.

Results

Most of the respondents considered AR (96.0%) and allergic asthma (96.0%) the most suitable indications for SIT. Of all respondents, 77.0% recommended the application of SIT as early as possible; in addition, SIT was considered 'relatively controllable and safe' by most respondents (80.6%). The highest allergen-positive rate in AR was associated with house dust mite (47.7%) and obvious differences existed among geographical regions. Conventional subcutaneous immunotherapy was the most highly recommended treatment option (96.2%). 'The high cost of SIT' (86.6%) and 'lack of patient knowledge of SIT' (85.2%) were probably the main reasons for the lower clinical use of SIT in China.

Conclusions

Most cases showed that the opinions of Chinese ENT specialists appeared to be in agreement with recent SIT progress and international guidelines; however, many areas still need to enhance the standardization and use of SIT in China. Clinical guidelines for SIT require improvement; in addition, Chinese ENT specialists need continuing medical education on SIT.

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is a common inflammatory disease of the nasal mucosa that results from seasonal or perennial responses to allergens. AR is a global health problem and represents an important illness that interferes with daily activities and impairs sleep quality.1 The management of AR includes allergen avoidance, pharmacotherapy, specific immunotherapy (SIT), and patient education. As a hallmark of AR treatment, SIT is the only current medical intervention that can potentially affect the natural course of allergic diseases.2

Research on and the clinical practice of SIT has shown remarkable progress3 since Noon first described immunotherapy for AR in 1911.4 The efficacy and safety of SIT have been established by many clinical trials, studies, and meta-analyses; in addition, SIT has a long-term effect and can prevent the progression of allergic diseases.5,6,7,8 SIT is a suitable but uncommon treatment option for AR in China that is available only in a few major cities. Factors that may account for this include the insufficient extent of SIT acceptance by doctors and patients, the potential risk of anaphylaxis, and the relatively high cost of treatment.

ENT (ear, nose, and throat) specialists in China are responsible for the primary management of AR. To investigate current trends to utilize SIT in AR management, we designed a detailed survey to assess the attitude and understanding of SIT among Chinese ENT specialists. The results of this survey will help policy makers promote and standardize the usage of SIT in China.

We designed and distributed a questionnaire to 800 ENT specialists in January and February of 2011 who were working in 18 provinces and municipalities representative of 4 different geographical regions (east, south-central, west, and north) in China. Respondents were randomly selected from hospitals that perform SIT for allergic diseases. The survey included 22 questions distributed across three sections (see Supplementary Material): (A) 3 questions on the description of SIT, (B) 16 questions covering the theoretical and practical knowledge of SIT, and (C) 4 questions about the prospect of SIT in China. The study protocol was approved by the Chinese Medical Association and the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University.

A total of 800 questionnaires were distributed with a completed response rate of 781 (97.6%) surveys. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the voluntary participants. Each respondent received an explanatory statement at the beginning of the questionnaire and completed individual questionnaires under the supervision of a member of the trained research group.

Data obtained from the study were entered into a database for analysis. Results were expressed as the percentage of responses to each question. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

For all participants interviewed, the 3 most important factors for the implementation of SIT were a standardized diagnostic process (92.7%), professionally trained staff (92.0%), and a valid emergency rescue system (90.5%). Data revealed that only 15.8% of Chinese ENT specialists believed SIT could be implemented in a primary hospital.

The majority of ENT specialists considered AR (96.0%) and allergic asthma (96.0%) the most suitable diseases for SIT treatment, and nearly two-thirds also considered atopic dermatitis (62.0%) appropriate for treatment. Furthermore, 77.0% of respondents recommended initiation of SIT as early as possible.

Fig. 1 illustrates the allergen-positive rates in AR based on the past clinical practice experiences reported by ENT specialists. The positive rate for house dust mite (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus or Dermatophagoides farinae) was highest (47.7%), followed by a combination of D. pteronyssinus and D. farinae (32.1%), and then single pollen (22.1%). The prevalence of house dust mite sensitization in East China was higher than that observed in the other 3 regions; however, the highest prevalence of pollen allergy occurred in North China.

Table 2 summarizes the SIT experiences of ENT specialists. Doctors in South China preferred SIT as 'the treatment of first choice' (69.1%); however, those in West China preferred the choice 'pharmacotherapy is invalid' (78.2%). Compared to the other 3 regions, more doctors in South China agreed with 'conventional immunotherapy' (96.2%) and more doctors in West China agreed with 'rush immunotherapy' (54.4%). In regard to the method of SIT administration, more doctors in West China chose 'application of a single allergen' (66.6%), more doctors in East China chose 'a variety of allergens, itemized desensitization' (45.3%), and more doctors in South China chose 'a variety of allergens, mixed desensitization' (40.6%).

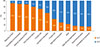

Most ENT specialists preferred a standardized allergen diagnosis (75.2%) and treatment (81.3%) in regard to allergen standardization; however, many thought that the stability of concentration (78.1%) and potency (75.6%) were also important factors. In descending order of preference, the 4 main evaluation methods of SIT were subjective symptoms (85.1%), serum IgE levels (68.0%), objective examination (65.5%), and inflammatory markers (59.9%). In terms of the choice between subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) and sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT), doctors tended to choose SCIT for cases in which consultation is convenient (85.3%), in which patients have good financial status (84.1%), have high-efficacy expectations (82.5%), are adult (76.4%) or are well-educated (71.5%) (Fig. 2).

ENT specialists in this survey generally believed that most representative approaches to immunotherapy were recombinant allergens (60.5%) and hypoallergenic allergens (60.9%) (Fig. 3). The majority of the respondents considered SIT 'relatively controllable and safe' (80.6%) and only a few regarded SIT 'uncontrollable and unsafe' (11.0%) (Fig. 4).

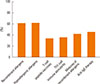

SIT dosing schedules (72.7%) and delivery method recommendations (72.3%) were the most-requested guidelines by Chinese ENT specialists (Fig. 5A). Most respondents considered 'the high cost of SIT' (86.6%) and 'lack of patient knowledge about SIT' (85.2%) the main reasons for the low clinical use of SIT in China (Fig. 5B).

This questionnaire-based survey provided an updated description of knowledge and perception of SIT in Chinese otolaryngologists. The results showed that the opinions of most doctors were in agreement with the recent progress and international guidelines in regard to SIT; however, there are still many areas for improvement in the promotion and standardization of SIT in China. To our knowledge, this is the first nationwide survey of SIT conducted in China, and it provides useful insight on current SIT beliefs and future training requirements for Chinese ENT specialists.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and other academic organizations have published several guidelines and position papers over the past 2 decades on the SIT of inhalant allergens.1,2,8,9,10 These documents were the basis for the design of our questionnaire. The European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) suggests that SIT be performed in specialized allergy centers with valid emergency rescue systems and professionally trained staff. These professionally trained staff should have adequate knowledge of the standard diagnostic process as well as the ability to recognize and treat early symptoms and signs of anaphylaxis.2 Our survey results are in agreement with these principles. It is significant that most of the respondents recommended the application of SIT as early as possible. This suggestion shows that the vast majority of Chinese ENT specialists consider SIT a relatively safe and efficacious treatment for allergic diseases. However, Chinese otolaryngologists are increasingly open to the concept that SIT is capable of inducing modifications in the immunological pattern of allergic patients.

The results of the present survey suggest that ENT specialists most commonly encounter patients with AR triggered by one or two kinds of inhalant allergens. One recent multicentre clinical study11 analyzed 6,304 patients suffering from asthma and/or rhinitis in 17 cities in 4 regions of China. The study found that house dust mites were the major allergen among patients; in addition, those in northern China showed significantly greater sensitization to pollen than those from the other 3 regions. Consistent with previous observations,12 we found there were differences in allergen-positive rates in AR reported by our interviewers from different geographical areas.

Chinese guidelines recommend SIT for AR patients who are allergic to one or two aeroallergens (particularly house dust mite sensitization).13,14 British investigators also suggest the application of a mono-sensitized allergen during SIT and believe that a single-allergen vaccine is more effective than vaccines that contain allergen mixtures.10 However, AR is often induced by a variety of allergens, and the safety and effectiveness of a multi-allergen SIT is still debatable. Some clinical trials have shown that multiple-allergen immunotherapy is effective in AR and asthma,15,16,17 but others have not.18,19 Multiple-allergen immunotherapy increases the risk of adverse reactions during SIT.20,21 In our survey, nearly half of the respondents supported the use of monotherapy and almost two-thirds of the respondents supported multi-allergen SIT (itemized and mixed desensitization). This finding suggests that ENT specialists in China tend to treat patients for multiple clinically relevant sensitivities and is similar to the patient treatment used in the United States.22 Randomized controlled trials involving SIT with a variety of allergens are needed to determine the safety and efficacy of the multi-allergen mixture. In addition, only 3 kinds of standardized and licensed allergen extracts (of D. pteronyssinus and D. farinae) are available for SIT in China. Other standardized allergens (such as grass and tree pollens) are currently unavailable and represent a significant limitation of SIT development in China.

The overwhelming majority of respondents preferred conventional immunotherapy (i.e., SCIT) dosing schedules that require several injections over 3 months to reach a maintenance dose; however, this relatively long up-dosing phase can affect patient compliance and acceptance.23 Doctors and patients both desire a shorter up-dosing schedule and a faster onset of symptom relief; subsequently, cluster immunotherapy and rush immunotherapy have been developed as accelerated procedures to achieve the maintenance dose.24,25,26,27,28 The accelerated buildup of SITs have been proven to be efficient and convenient; however, they are prescribed for only a small percentage of patients with AR in China.28 The relatively higher rate of systemic reactions produced by these immunotherapies is believed to be a major reason for this. This study also revealed that the awareness of cluster and rush immunotherapies (as well as treatment potential) is inadequate for Chinese otolaryngologists. More studies are required to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the 2 types of SCIT. Chinese ENT specialists should update their knowledge of various SIT treatment programs and select suitable dosing schedules for SIT according to risk factors for systemic reactions, patient response, and choice as well as product.10,29

SIT has traditionally been administered as subcutaneous injections; however, the inconvenience and local or systemic adverse reactions associated with the subcutaneous approach are frequently cited concerns.23,30,31 Over the last 3 decades, the sublingual route (an alternative route for the delivery of immunotherapy) has gained wide acceptance in many countries.9 This survey recognized SLIT as a more accessible and affordable treatment for AR. Chinese ENT specialists determine the administration route in accordance with the specific conditions of patients that include attitude and compliance, financial status, risk factors for systemic reactions, and age. In China, SLIT has gained increased acceptance and is considered an effective and safe treatment in clinical practice.13,14,32

Efforts to develop safer and more effective novel approaches to immunotherapy have resulted in several modifications of allergen extracts.22 In this survey, more than half of the ENT specialists prefer recombinant allergens and hypoallergenic allergens as new molecular approaches to SIT. Both of these allergen formulations are composed of recombinant proteins, which are quantifiable, reproducible, and available in large quantities.10 Recombinant hypoallergenic variants can reduce the risk of anaphylaxis and preserve antigenicity that allow for the administration of larger doses typically used in normal allergen extracts. Recent studies have shown that vaccination with recombinant proteins demonstrated clinical efficacy with no IgE-mediated side effects.33,34 The present survey suggests that this kind of allergy vaccine may have a potential clinical application in China. In addition, most respondents voiced their consideration of other therapeutic strategies, such as T-cell peptide vaccines, Th1-cell immune stimulants and anti-IgE therapy that represent important areas of research in the development of SIT.35 Chinese otolaryngologists may be interested in major technological advances in SIT; however, relevant and current studies are still limited in China.

The present survey also explored the perceptions of the safety of SIT among Chinese ENT specialists. Most respondents had a positive image of SIT therapy, and the majority of experts (such as professors, consultant otolaryngologists, and doctors aged 45 or above) considered SIT a relatively safe treatment. A greater percentage of respondents in West China (53.0%) expressed concern over severe complications from SIT. This concern may be attributable to differences in clinical experiences. Experienced clinicians have more opportunity to understand SIT and apply it to patients. They have a growing belief that SIT is safe and effective on the basis of first-hand experience gained from clinical practice. Our results suggest that SIT is not widely available in West China. In addition, this survey also indicates that nearly 40% of ENT specialists lack SCIT systemic reaction grading system knowledge;2,36 subsequently, continuing education and training in this field should be strengthened. The grading system is helpful to more accurately and effectively assess and deal with adverse SIT reactions that can enhance the safety of SIT. Allergen standardization could possibly guarantee the effectiveness of SIT as well as maintain high safety standards.10 Most of the ENT specialists in this survey recommended the standardization of allergens for the diagnosis and treatment of respiratory allergic diseases. No uniform standards for the production of high-quality allergen extracts for SCIT have been developed in China, and this remains an area of considerable importance to clinicians.

This study also examined why SIT is used less frequently in China, from the viewpoint of an otolaryngologist. The 3 most common reasons are the high cost of SIT, lack of patient SIT knowledge, and lack of professional training for doctors. A possible explanation for this is the inadequate attention of patients, doctors, and public health policy-makers towards SIT. The treatment costs of SIT are relatively greater for the average family in a developing country. However, this therapy for allergic patients can improve the quality of life, reduce long-term costs, the physical burden of allergies, and change the course of the disease.37 SIT is cost-effective when compared to the increased costs of pharmacological treatments due to its efficacy and long-term benefits. Recent studies have shown a significant SIT cost-benefit versus the use of drugs alone for AR and asthma;38,39 however, the awareness of SIT and its treatment potential is inadequate in Chinese doctors as well as the majority of ENT specialists who consider SIT an expensive AR treatment. In most regions of China, the healthcare system does not cover the costs of SIT, or the Medicare payment for SIT is low. Both situations increase the burden of patients and are a direct consequence of negligence by healthcare policy makers. More healthcare policies should be adopted to promote immunotherapy awareness and support the implementation of SIT for allergic disease.

Certain limitations of our survey should be mentioned. First, most respondents were practicing in main tertiary hospitals in major cities and may not be representative of general practitioners and rural doctors; consequently, the results of our survey are limited to nationwide trends in SIT. The penetration rate of SIT might be lower than our results suggest due to the obvious differences between the medical resources of major cities and other parts of China. However, we maintain that our results are reliable, valid, and valuable because the majority of patients in China are treated in large general hospitals. It is possible that there are some errors in the results because of the methodology used. This was not a longitudinal study, and we could not examine the findings by objective verification measures (i.e., through medical record review or tests of physician knowledge); consequently, a recall bias and overestimation are likely in the self-reported data and may contribute to a degree of inaccuracy.

In summary, the majority of otolaryngologists in China accept that SIT is of great value in the treatment of allergic diseases. In the survey, the majority of the respondents considered AR and allergic asthma the most suitable diseases for SIT, which is relatively controllable and safe. Conventional SCIT is the preferred treatment method in China; however, SLIT has continued to gain acceptance. House dust mites were the most prevalent allergens encountered by these respondents; however, ENT specialists are also interested in other standardized allergens, multi-allergen mixtures, and recombinant allergens despite the fact that not all of them are currently available in China. SIT has received inadequate attention throughout China; subsequently, there is a need to improve Chinese SIT guidelines and provide continuing medical education for ENT specialists. The results of our survey are an important reference for government, industry, and academic circles to promote and standardize the use of SIT in China.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

Factors affecting the choice between subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) and sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) by Chinese ENT specialists.

Fig. 5

Questions regarding the aspects of SIT guidelines that need improvement (A), and the reasons for the low treatment rates of SIT in China (B).

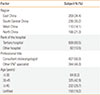

Table 1

General characteristics of the ENT specialists surveyed in the study (N=781)

Table 2

Clinician-reported experience of SIT (N=781).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD 2010-2013) and the Health Promotion Project of Jiangsu Province (RC2011071), the People's Republic of China.

References

1. Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, Denburg J, Fokkens WJ, Togias A, Zuberbier T, Baena-Cagnani CE, Canonica GW, van Weel C, Agache I, Aït-Khaled N, Bachert C, Blaiss MS, Bonini S, Boulet LP, Bousquet PJ, Camargos P, Carlsen KH, Chen Y, Custovic A, Dahl R, Demoly P, Douagui H, Durham SR, van Wijk RG, Kalayci O, Kaliner MA, Kim YY, Kowalski ML, Kuna P, Le LT, Lemiere C, Li J, Lockey RF, Mavale-Manuel S, Meltzer EO, Mohammad Y, Mullol J, Naclerio R, O'Hehir RE, Ohta K, Ouedraogo S, Palkonen S, Papadopoulos N, Passalacqua G, Pawankar R, Popov TA, Rabe KF, Rosado-Pinto J, Scadding GK, Simons FE, Toskala E, Valovirta E, van Cauwenberge P, Wang DY, Wickman M, Yawn BP, Yorgancioglu A, Yusuf OM, Zar H, Annesi-Maesano I, Bateman ED, Ben Kheder A, Boakye DA, Bouchard J, Burney P, Busse WW, Chan-Yeung M, Chavannes NH, Chuchalin A, Dolen WK, Emuzyte R, Grouse L, Humbert M, Jackson C, Johnston SL, Keith PK, Kemp JP, Klossek JM, Larenas-Linnemann D, Lipworth B, Malo JL, Marshall GD, Naspitz C, Nekam K, Niggemann B, Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E, Okamoto Y, Orru MP, Potter P, Price D, Stoloff SW, Vandenplas O, Viegi G, Williams D. World Health Organization. GA2LEN. AllerGen. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA2LEN and AllerGen). Allergy. 2008; 63:Suppl 86. 8–160.

2. Alvarez-Cuesta E, Bousquet J, Canonica GW, Durham SR, Malling HJ, Valovirta E. EAACI, Immunotherapy Task Force. Standards for practical allergen-specific immunotherapy. Allergy. 2006; 61:Suppl 82. 1–20.

3. Akkoc T, Akdis M, Akdis CA. Update in the mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotheraphy. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011; 3:11–20.

4. Noon L. Prophylactic inoculation against hay fever. Lancet. 1911; 177:1572–1573.

5. Pajno GB, Barberio G, De Luca F, Morabito L, Parmiani S. Prevention of new sensitizations in asthmatic children monosensitized to house dust mite by specific immunotherapy. A six-year follow-up study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001; 31:1392–1397.

6. Jacobsen L, Niggemann B, Dreborg S, Ferdousi HA, Halken S, Høst A, Koivikko A, Norberg LA, Valovirta E, Wahn U, Möller C. (The PAT investigator group). Specific immunotherapy has long-term preventive effect of seasonal and perennial asthma: 10-year follow-up on the PAT study. Allergy. 2007; 62:943–948.

7. Durham SR, Emminger W, Kapp A, Colombo G, de Monchy JG, Rak S, Scadding GK, Andersen JS, Riis B, Dahl R. Long-term clinical efficacy in grass pollen-induced rhinoconjunctivitis after treatment with SQ-standardized grass allergy immunotherapy tablet. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 125:131–138.e1-7.

8. Allergen immunotherapy: therapeutic vaccines for allergic diseases. Geneva: January 27-29 1997. Allergy. 1998; 53:1–42.

9. Canonica GW, Bousquet J, Casale T, Lockey RF, Baena-Cagnani CE, Pawankar R, Potter PC, Bousquet PJ, Cox LS, Durham SR, Nelson HS, Passalacqua G, Ryan DP, Brozek JL, Compalati E, Dahl R, Delgado L, van Wijk RG, Gower RG, Ledford DK, Filho NR, Valovirta EJ, Yusuf OM, Zuberbier T, Akhanda W, Almarales RC, Ansotegui I, Bonifazi F, Ceuppens J, Chivato T, Dimova D, Dumitrascu D, Fontana L, Katelaris CH, Kaulsay R, Kuna P, Larenas-Linnemann D, Manoussakis M, Nekam K, Nunes C, O'Hehir R, Olaguibel JM, Onder NB, Park JW, Priftanji A, Puy R, Sarmiento L, Scadding G, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Seberova E, Sepiashvili R, Solé D, Togias A, Tomino C, Toskala E, Van Beever H, Vieths S. Sub-lingual immunotherapy: World Allergy Organization Position Paper 2009. Allergy. 2009; 64:Suppl 91. 1–59.

10. Walker SM, Durham SR, Till SJ, Roberts G, Corrigan CJ, Leech SC, Krishna MT, Rajakulasingham RK, Williams A, Chantrell J, Dixon L, Frew AJ, Nasser SM. British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011; 41:1177–1200.

11. Li J, Sun B, Huang Y, Lin X, Zhao D, Tan G, Wu J, Zhao H, Cao L, Zhong N. China Alliance of Research on Respiratory Allergic Disease. A multicentre study assessing the prevalence of sensitizations in patients with asthma and/or rhinitis in China. Allergy. 2009; 64:1083–1092.

12. Shi HB, Cheng L, Enomoto T, Takahashi Y, Sahashi N, Shirakawa T, Miyoshi A. Recent advances in pollen survey and pollinosis research in China. Jpn J Palynol. 2002; 48:109–127.

13. Zhu L, Lu JH, Xie Q, Wu YL, Zhu LP, Cheng L. Compliance and safety evaluation of subcutaneous versus sublingual immunotherapy in mite-sensitized patients with allergic rhinitis. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2010; 45:444–449.

14. Zhu L, Zhu LP, Chen RX, Tao QL, Lu JH, Cheng L. Clinical efficacy of subcutaneous and sublingual immunotherapy in mite-sensitized patients with allergic rhinitis. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2011; 46:986–991.

15. Calderón MA, Cox L, Casale TB, Moingeon P, Demoly P. Multiple-allergen and single-allergen immunotherapy strategies in polysensitized patients: looking at the published evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012; 129:929–934.

16. Jutel M, Jaeger L, Suck R, Meyer H, Fiebig H, Cromwell O. Allergen-specific immunotherapy with recombinant grass pollen allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005; 116:608–613.

17. Nelson HS. Multiallergen immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 123:763–769.

18. Amar SM, Harbeck RJ, Sills M, Silveira LJ, O'Brien H, Nelson HS. Response to sublingual immunotherapy with grass pollen extract: monotherapy versus combination in a multiallergen extract. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 124:150–156.e1-5.

19. Adkinson NF Jr, Eggleston PA, Eney D, Goldstein EO, Schuberth KC, Bacon JR, Hamilton RG, Weiss ME, Arshad H, Meinert CL, Tonascia J, Wheeler B. A controlled trial of immunotherapy for asthma in allergic children. N Engl J Med. 1997; 336:324–331.

20. Eifan AO, Keles S, Bahceciler NN, Barlan IB. Anaphylaxis to multiple pollen allergen sublingual immunotherapy. Allergy. 2007; 62:567–568.

21. Dunsky EH, Goldstein MF, Dvorin DJ, Belecanech GA. Anaphylaxis to sublingual immunotherapy. Allergy. 2006; 61:1235.

22. Cox L, Nelson H, Lockey R, Calabria C, Chacko T, Finegold I, Nelson M, Weber R, Bernstein DI, Blessing-Moore J, Khan DA, Lang DM, Nicklas RA, Oppenheimer J, Portnoy JM, Randolph C, Schuller DE, Spector SL, Tilles S, Wallace D. Allergen immunotherapy: a practice parameter third update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011; 127:S1–S55.

23. Cohn JR, Pizzi A. Determinants of patient compliance with allergen immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993; 91:734–737.

24. Cox L. Accelerated immunotherapy schedules: review of efficacy and safety. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006; 97:126–137.

25. Finegold I. Allergen immunotherapy: present and future. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007; 28:44–49.

26. Cox LS. Shooting for a faster approach to the immunotherapy target: will cluster become conventional? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009; 102:177–178.

27. Schubert R, Eickmeier O, Garn H, Baer PC, Mueller T, Schulze J, Rose MA, Rosewich M, Renz H, Zielen S. Safety and immunogenicity of a cluster specific immunotherapy in children with bronchial asthma and mite allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2009; 148:251–260.

28. Zhang L, Wang C, Han D, Wang X, Zhao Y, Liu J. Comparative study of cluster and conventional immunotherapy schedules with dermatophagoides pteronyssinus in the treatment of persistent allergic rhinitis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2009; 148:161–169.

29. Copenhaver CC, Parker A, Patch S. Systemic reactions with aeroallergen cluster immunotherapy in a clinical practice. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011; 107:441–447.

30. More DR, Hagan LL. Factors affecting compliance with allergen immunotherapy at a military medical center. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002; 88:391–394.

31. Radulovic S, Wilson D, Calderon M, Durham S. Systematic reviews of sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT). Allergy. 2011; 66:740–752.

32. Wang DH, Chen L, Cheng L, Li KN, Yuan H, Lu JH, Li H. Fast onset of action of sublingual immunotherapy in house dust mite-induced allergic rhinitis: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Laryngoscope. 2013; 123:1334–1340.

33. Valenta R, Linhart B, Swoboda I, Niederberger V. Recombinant allergens for allergen-specific immunotherapy: 10 years anniversary of immunotherapy with recombinant allergens. Allergy. 2011; 66:775–783.

34. Larché M. Update on the current status of peptide immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007; 119:906–909.

35. Valenta R, Campana R, Marth K, van Hage M. Allergen-specific immunotherapy: from therapeutic vaccines to prophylactic approaches. J Intern Med. 2012; 272:144–157.

36. Cox L, Larenas-Linnemann D, Lockey RF, Passalacqua G. Speaking the same language: the World Allergy Organization subcutaneous immunotherapy systemic reaction grading system. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 125:569–574. 574.e1–574.e7.

37. Akdis C, Papadopoulos N, Cardona V. Fighting allergies beyond symptoms: the European Declaration on Immunotherapy. Eur J Immunol. 2011; 41:2802–2804.

38. Ariano R, Berto P, Tracci D, Incorvaia C, Frati F. Pharmacoeconomics of allergen immunotherapy compared with symptomatic drug treatment in patients with allergic rhinitis and asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2006; 27:159–163.

39. Omnes LF, Bousquet J, Scheinmann P, Neukirch F, Jasso-Mosqueda G, Chicoye A, Champion L, Fadel R. Pharmacoeconomic assessment of specific immunotherapy versus current symptomatic treatment for allergic rhinitis and asthma in France. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007; 39:148–156.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download