Abstract

Purpose

Recent studies have used the term "gastroallergic anisakiasis" to describe incidental gastrointestinal infection with Anisakis spp. larvae, proposed as a causative agent of food hypersensitivity. However, it is unknown whether this condition represents an independent disease entity distinguishable from acute gastric anisakiasis. To better understand the role of the allergic response in Anisakis infections we examined the clinical and immunological implications of Anisakis-specific IgE.

Methods

A prospective study was performed in a geographic region where the consumption of raw seafood is common. Case subjects who had been clinically diagnosed with gastroallergic anisakiasis were selected, along with controls who frequently ate raw seafood but had never experienced gastroallergic anisakiasis-like symptoms. Clinical and immunological features were compared based on atopic status, sensitization rates to Anisakis, and serum titer of Anisakis-specific IgE.

Results

Seventeen case subjects and 135 controls were included in this study. The case subjects had experienced gastrointestinal symptoms after raw seafood ingestion, along with additional mucocutaneous, respiratory, or multisystemic symptoms. Case subjects were significantly sensitized to Anisakis excretory-secretory product and crude extract compared with controls (76.5% vs 19.3%, P<0.001, and 88.2% vs 30.3%, P<0.001, respectively). Anisakis-specific serum IgE titers were also significantly higher in case subjects than in controls. Both the results of skin prick tests and elevated Anisakis-specific IgE titers (>17.5 kU/L) were found to be reliable indicators for the diagnosis of gastroallergic anisakiasis.

Anisakis is a genus of parasitic nematodes belonging to the family Anisakidae. The life cycle of this organism includes free-living forms, along with parasitic stages involving crustaceans, fish, and marine mammals, including whales, seals, and dolphins. In humans, anisakiasis is an incidental gastrointestinal infestation derived from uncooked marine seafood, which is caused by parasitization by the third-stage larvae of Anisakis simplex or Pseudoterranova decipiens (Anisakis spp.). When parasitized seafood is consumed, the Anisakis larvae are normally coughed up before they penetrate the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract. However, when mucosal penetration does occur, violent upper abdominal pain with nausea occurs within a few hours of ingestion; this is known as acute gastric anisakiasis. The extraction of larvae via upper endoscopy is the treatment of choice.1,2,3 Relatively rare cases of acute gastric anisakiasis are encountered in clinical practice even in geographic regions where the consumption of raw marine seafood is habitual, such as Jeju in Korea.4,5

Reports of acute gastric anisakiasis in the literature are extremely rare even in the region where raw seafood is consumed, given that a large proportion of seafood is infected with Anisakis spp.4,6 In some cases, clinical symptoms not associated with the gastrointestinal system have been reported. It was suggested that the symptoms and signs of anisakiasis are caused by an immediate, IgE-mediated immunological reaction to Anisakis antigens, as Anisakis spp.-specific IgE was identified in patients' sera after the reaction.7,8,9,10,11 This type of food hypersensitivity has been referred to as gastroallergic anisakiasis, and is considered distinct from acute gastric anisakiasis.12,13,14,15,16 However, it remains unclear whether gastroallergic anisakiasis constitutes an independent disease distinguishable from acute gastric anisakiasis.

In a general hospital in Jeju, Korea, where the consumption of raw seafood is common and habitual, we enrolled 17 cases of gastroallergic anisakiasis along with a control group consisting of patients who had never experienced a reaction to raw seafood, despite frequent consumption. We conducted a case control study examining the clinical and immunological aspects of each group, and explored the diagnostic implications of Anisakis-specific IgE, and IgE responses to selected antigens.

Patients presenting to Jeju National University Hospital, Korea, between 2006 and 2009, with suspected gastroallergic anisakiasis, selected by an allergist and were enrolled as case subjects with informed consents. To qualify, the case subjects had to be habitual consumers of raw seafood and have a medically observed history of IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction. Clinical manifestations included one or more of the following symptoms within a few hours of ingesting raw seafood: hives, swollen face, abdominal pain, shortness of breath, and diarrhea. Clinical symptoms had to correlate with the recent consumption of raw seafood in each individual case; subjects were excluded if a causative agent other than Anisakis spp. was specified. A detailed clinical history was recorded for each subject. Skin prick tests were requested and sera were collected for Anisakis-specific IgE tests.

Patients from the allergy clinic at Jeju National University Hospital were recruited as control subjects for this study, screened based on the following simple questions: (1) Have you experienced an abrupt onset of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or diarrhea in the last 5 years? (2) Have you experienced the abrupt onset of hives or swelling of the face in the last 5 years? (3) Did these symptoms occur immediately (no more than a few hours) after consuming raw seafood? (4) Have you ever been diagnosed or treated for anisakiasis?

Subjects who gave appropriate answers to all questions were invited to enroll in the control group with informed consent. Skin prick tests and sera for Anisakis spp.-specific IgE tests were requested from the control subjects as necessary.

The intestines of live sea eels were obtained from a fish market in Jeju, Korea. Viable Anisakis worms measuring 0.5 mm in diameter and 15-20 mm in length were collected from the internal walls of the fish intestines and were kept in sterile 0.9% saline. Species identity was confirmed by a parasitologist.

Intact, actively moving worms were incubated in saline at 37℃ for 48 hours. All of the visible debris and worm bodies were then removed by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 30 minutes. The supernatant was dialyzed (Spectra/Por MWCO 6,000-8,000) with distilled water at 4℃ for 12 hours and lyophilized (Heto-Holten, Denmark). The lyophilized powder was then resolubilized in 0.9% saline to a total protein concentration of 0.3 mg/mL. The resulting solution, referred to as the excretory-secretory product (ESP) of Anisakis spp., was then mixed with 50% glycerol in equal volumes and used in the skin tests.

Non-viable worms collected from the fish intestines were homogenized using a cylindrical Teflon pestle (Schuett-biotec GmbH, Göttingen, Denmark). After centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 30 minutes, the supernatant was dialyzed, lyophilized, and then resolubilized to a concentration of 3.0 mg/mL protein, as described above. This solution was referred to as the crude extract of Anisakis spp. and used for the skin prick tests.

Using the ImmunoCAP® (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) system, Anisakis spp.-specific IgE in each patient's serum was measured and expressed as kU/L. IgE levels were then classified on a scale of 0-6, (< 0.1, 0.35-0.69, 0.70-3.4, 3.5-17.4, 17.5-49.9, 50.0-99.9, and ≥100, respectively), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Serum titers were further categorized into low-(class 0-1), middle-(classes 2-3) and high-(classes 4-6) titer groups for the purpose of this study.

For case subjects, the skin prick tests were delayed for at least 3 weeks after resolution of clinical symptoms. Skin prick tests were performed on the volar side of the forearm using 26-gauge disposable needles, including positive (histamine, 1 mg/mL) and negative (50% glycerol) controls. The result of each test was expressed as the largest diameter of the wheal on the skin.

Atopy was defined as a positive reaction (wheal diameter ≥3 mm) to one or more common sensitizing inhalant allergens, i.e., Dermatophagoides farinae, D. pteronyssinus, Tyrophagus putrescentiae, cockroach, a grass pollen mixture, mugwort, ragweed, Japanese hops, tree pollen mixtures, animal hair mixtures, mold mixtures (Allergopharma, Reinbek, Germany), Japanese cedar (Greer, Lenoir, NC), and Panonychus citri.17

For skin prick tests using either ESP or crude extract, cut-offs for positive tests were defined using receiver operating characteristic curves which measured the sensitivity and true negative rates for wheal sizes in both case subjects and controls.

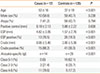

Seventeen cases (mean age, 53±16 years; male 58.8%) were enrolled in the study. Another 135 subjects (mean age, 37±19; male 43.7%) who had not previously experienced any symptoms related to anisakiasis infestation were enrolled as controls (Table 1).

Skin prick tests for common aeroallergens were positive for 7 cases and 59 control subjects. There was no difference in atopic sensitization between the cases and controls (41.2% vs 43.7%, respectively; P=0.794). The skin reactivity to histamine controls was similar between case and control subjects (6.18±2.13 vs 5.88±2.22 mm, respectively; P=0.60).

The 17 case subjects reported a range of symptoms affecting their mucocutaneous, gastrointestinal, or respiratory systems. Symptoms were most frequent in the gastrointestinal system (12 subjects, 70.5%), followed by the mucocutaneous system (35.3%), and the respiratory system (11.8%); three subjects (17.6%) experienced multisystemic symptoms. Most subjects were able to recall the seafood dishes, which were extremely diverse, with yellowtail being the most common. Thirteen subjects (76.5%) had never experienced anisakiasis-like symptoms prior to this event, whereas the other four patients had experienced repeated incidents. Upper endoscopy was performed in 4 cases; larvae were detected in only one case; however, gastric mucosal erosions were evident in all 4 patients. Two larvae were removed from a single case, then epigastric pain subsided. In patients experiencing acute urticaria or angioedema, all of the diagnostic tests for food hypersensitivity were negative, though not all patients received the full range of diagnostic tests (Table 2).

In skin prick tests, case subjects produced larger wheals in response to ESP and crude extract than controls. The mean wheal size in response to ESP was 4.82±3.05 mm in the case subjects compared to 1.57±2.76 mm in controls (P<0.001). Using a wheal size measurement of ≥4 mm as an arbitrary definition of a positive reaction, 76.5% of case subjects and 19.3% of controls exhibited positive reactions to ESP (P<0.001).

The wheals produced in response to crude extract were also significantly larger in case subjects than in controls (8.06±5.40 vs. 3.00±5.36 mm, respectively; P<0.001). Using the same definition for a positive reaction as before, 88.2% of the case subjects and 30.3% of controls exhibited positive reactions (Table 1). Compared to the reactivity seen against standardized aeroallergens, the optimal concentrations of ESP and crude extract for use in skin prick tests may be lower than those used in this study.

The serum concentration of Anisakis spp.-specific IgE was measured in 14 case and 29 control subjects. Case subjects exhibited significantly higher concentrations of Anisakis spp.-specific IgE (P<0.001). Among case subjects, all serum IgE concentration was categorized as class 2 or higher; three cases were seen for classes 2-3 (21.4%), and 11 cases were seen for classes 4-6 (78.6%). By contrast, more than half of the control subjects were categorized as low titer: 18 patients in classes 0-1 (62.1%), 6 patients in classes 2-3 (20.7%), and 5 patients in classes 4-6 (17.2%; Table 1).

The sensitivity and specificity of each immunological test was calculated using Anisakis spp.-specific IgE. A wheal size of ≥4 mm was defined as the cutoff for positivity in the skin prick tests, and the low (classes 0-1) and high (classes 4-6) titers groups for serum Anisakis spp.-specific IgE were measured using ImmunoCAP. All of the immunological tests performed in this study were reliable with both high sensitivity and specificity; however, the more broadly defined high-titer group (classes 4-6) for Anisakis spp.-specific IgE, as measured using ImmunoCAP, may be the most useful diagnostic test. This method could therefore be used to rule out gastroallergic anisakiasis in patients presenting with typical clinical manifestations and a low serum IgE titer (classes 0-1) (Table 3).

Incidental infestations of Anisakis spp. in the human gastrointestinal tract are often seen in areas where the consumption of raw seafood is common, such as Japan and Korea. In contrast to other parasitic infestations, which are rarely encountered in developed countries, the incidence of anisakiasis may be increasing due to the growing popularity of raw seafood dishes worldwide.1,18 The host sea creatures of Anisakis spp. appear to be extremely diverse, which suggests that, in theory, almost all raw seafood could be infested. In Jeju, an analysis of 107 acute anisakiasis cases found that affected species included cuttlefish, yellow corvina, sea eel, ling, fatfish, yellowtail, scabbard fish, sea bream, common octopus, and others. In particular, yellow corvina, sea eel, ling, and yellowtail were the most common.4 While exposure to Anisakis spp. antigens may be unavoidable for habitual consumers of raw seafood, there have been no reports of gastroallergic anisakiasis resulting from cooked seafood, suggesting that the associated antigens are either heat labile or produced only by live larvae.

The gastrointestinal symptoms of acute gastric anisakiasis had long been considered a consequence of the physical and mechanical irritation caused by worms penetrating the gastric mucosa. It was therefore suggested that diagnosis of this condition should be made by direct visualization of the larvae via upper endoscopy, with a recommended course of treatment being mechanical extraction of larvae.1 However, the physical and mechanical irritation caused by acute gastric anisakiasis may be much milder than that caused by a forceps biopsy during upper endoscopy.

Asymptomatic cases of Anisakis spp. infection may be more common than previously thought, as incidental findings of Anisakis larvae in the gastric or duodenal mucosal surface are occasionally seen in this region by experienced upper endoscopists. In these patients, endoscopic examination was performed because of minor dyspeptic symptoms or as part of an annual health checkup. In some cases, penetration of the larvae through the intestinal wall was observed. In a patient receiving peritoneal dialysis, a foreign body was found incidentally in the effluent dialysis fluid and Anisakis spp. larvae were confirmed.19 Therefore, the gastrointestinal symptoms of acute gastric anisakiasis might not be a consequence of mucosal penetration by the infesting larvae. As found with other food hypersensitivities, repeated exposure to Anisakis spp. is required before sensitization occurs. Given that specific antibodies to Anisakis spp. larvae can be induced in an animal model,20 seropositivity might simply be a result of repeated, incidental exposure to Anisakis spp. antigens.

Two distinct phenotypes of Anisakis spp. infection are hypothesized based upon differences in the host immune response to antigens. When exposed to Anisakis spp. antigens, a potent IgE-mediated response may result in a systemic allergic reaction leading to improved clearance of the infecting larvae. This hypothesis is consistent with clinical findings, as larvae are rarely observed during upper endoscopies, while allergic symptoms are common. Atopic individuals exposed to Anisakis spp. antigens might be easily sensitized and protected from acute gastric anisakiasis. Alternatively, failure to mount a sufficient IgE response against invading parasites could limit expulsion, resulting in acute gastric anisakiasis.16,21

The sensitization rates to Anisakis spp. in the general population range from 0.4% to 10%,11,22,23,24 and can reach 20% depending on atopic status, occupational exposure, and frequency of raw seafood consumption.25 In a multicenter study in Italy, the sensitization rates differed markedly from 0.4% in inland residents to 12.7% in coastal residents, suggesting that difference in anchovy-eating habits between the 2 regions may have affected the sensitization rate.24 In a Korean study,23 the seroprevalence was reported to be as low as 5% to 6% with crude and ESP antigens measured by ELISA. This rate is far lower than that detected in this study, although differences in the sensitivities and cutoff values used may make comparisons between these 2 studies difficult. In this study, sensitivities and specificities were determined using a skin prick test; however, this method has not been standardized in terms of the protein concentrations used.

Detection of Anisakis spp.-specific IgE may be useful for the diagnosis of gastroallergic anisakiasis. Among patients presenting with typical symptoms and signs of gastroallergic anisakiasis, prior sensitization may be a reliable indicator of disease, with gastroallergic cases more commonly seen in patients with high serum Anisakis-specific IgE. Although the skin prick test is a simpler and less costly method of detecting sensitization, we recommend Anisakis spp.-specific IgE tests using ImmunoCAP® as a diagnostic test in clinical settings.

Compared with the relatively high sensitization rates to Anisakis spp. antigens as a causative agent of food hypersensitivity, the prevalence of symptomatic anisakiasis is extremely low, suggesting that a large number of patients exposed to Anisakis spp. antigens do not experience clinical symptoms.24,26 Specific IgE for Anisakis ESP was detected in 87.5% of the endoscopically proven cases of acute gastric anisakiasis, but in only 10% of the normal controls. Specific IgE was detected in 75.0% of case subjects with mackerel-induced hives without gastrointestinal symptoms, but in only 8.3% and 10.0% of patients with urticaria of unknown origin and the normal controls, respectively.11

Surgical or endoscopic removal of larvae is the only effective treatment available for acute gastric anisakiasis.1,3,4 Upper endoscopic examinations were conducted in 4 of the 17 cases described in the present study. Suspected lesions were observed in two cases and two larvae were removed in one case. In most cases, the symptoms and signs were controlled by medical treatment. Even in the case of direct visualization and removal of the larvae, the majority of clinical symptoms were controlled using epinephrine, glucocorticoids, and antihistamines prior to endoscopic removal.27 In other case, she was tolerated for 15 hours after raw seafood ingestion with medical treatment except for epigastric pain, which was relieved by upper endoscopic removal of >200 larvae from her stomach.28

From the perspective of food hypersensitivity, the symptoms of gastroallergic anisakiasis are similar to those of other food hypersensitivities. We therefore cautiously suggest that standard treatments for food hypersensitivity may be effective in patients whose symptoms and signs mainly suggest a hypersensitivity reaction, although further investigations should be performed.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Demographic and immunological characteristics of gastroallergic patients and controls

Table 2

Clinical characteristics and immunological responses in 17 gastroallergic anisakiasis cases

Table 3

Sensitivity and specificity of various immunological tests for the diagnosis of gastroallergic anisakiasis

References

1. Weller PF, Nutman TB. Intestinal nematode infections. In : Longo DL, Kasper DL, Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 18th ed. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill;2012. p. 1739–1744.

2. Bouree P, Paugam A, Petithory JC. Anisakidosis: report of 25 cases and review of the literature. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995; 18:75–84.

3. Sugimachi K, Inokuchi K, Ooiwa T, Fujino T, Ishii Y. Acute gastric anisakiasis. Analysis of 178 cases. JAMA. 1985; 253:1012–1013.

4. Im KI, Shin HJ, Kim BH, Moon SI. Gastric anisakiasis cases in Cheju-do, Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1995; 33:179–186.

5. Kim SE, Kim SL, Lee KS, Kim JM, Jang MY, Cho JG, Lee HJ. 9 cases of acute gastric anisakiasis. Korean J Gastroenterol. 1991; 23:866–872.

6. Yang DH, Cho JK, Yoon CM, Suh SP, Kim SJ, Lim YK, Kim SR. Anisakis. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 1988; 8:133–136.

7. Yamamoto Y, Tachibana M, Sakaeda K, Okazaki K, Yamamoto Y. IgE-anisakis antibody in the sera of patients with acute gastric anisakiasis. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1984; 81:1489.

8. Tachibana M, Yamamoto Y. Serum anti-Anisakis IgE antibody in patients with acute gastric anisakiasis. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1986; 83:2132–2138.

9. Nakata H. Analysis of antigens defined by anti-anisakis larvae IG-G and IG-E antibodies in sera of patients with acute gastric anisakiasis. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1986; 83:2456.

10. Nakata H, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto Y. Analysis of antigens defined by anti-Anisakis larvae antibodies of IgE and IgG type in the sera of patients with acute gastrointestinal anisakiasis. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1990; 87:762–770.

11. Kasuya S, Koga K. Significance of detection of specific IgE in Anisakis-related diseases. Arerugi. 1992; 41:106–110.

12. López-Serrano MC, Gomez AA, Daschner A, Moreno-Ancillo A, de Parga JM, Caballero MT, Barranco P, Cabañas R. Gastroallergic anisakiasis: findings in 22 patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000; 15:503–506.

13. Daschner A, Alonso-Gómez A, Cabañas R, Suarez-de-Parga JM, López-Serrano MC. Gastroallergic anisakiasis: borderline between food allergy and parasitic disease-clinical and allergologic evaluation of 20 patients with confirmed acute parasitism by Anisakis simplex. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000; 105:176–181.

14. Kim SH, Kim HU, Lee J. A case of gastroallergic anisakiasis. Korean J Med. 2006; 70:111–116.

15. Daschner A. Sensitization to Anisakis simplex: inhalant allergy versus gastroallergic anisakiasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 118:968.

16. Daschner A, Rodero M, Cuéllar C. Low immunoglobulin E response in gastroallergic anisakiasis could be associated with impaired expulsion of larvae. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2011; 21:330–331.

17. Jeon BH, Lee J, Kim JH, Kim JW, Lee HS, Lee KH. Atopy and sensitization rates to aeroallergens in children and teenagers in Jeju, Korea. Korean J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 30:14–20.

18. Fernández de Corres L, Audícana M, Del Pozo MD, Muñoz D, Fernández E, Navarro JA, García M, Díez J. Anisakis simplex induces not only anisakiasis: report on 28 cases of allergy caused by this nematode. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 1996; 6:315–319.

19. Yeum CH, Ma SK, Kim SW, Kim NH, Kim J, Choi KC. Incidental detection of an Anisakis larva in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis effluent. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002; 17:1522–1523.

20. Yang HJ, Cho YJ, Paik YH. Changes of IgM and IgG antibody levels in experimental rabbit anisakiasis as observed by ELISA and SDS-PAGE/immunoblot. Korean J Parasitol. 1991; 29:389–396.

21. Nieuwenhuizen N, Lopata AL, Jeebhay MF, Herbert DR, Robins TG, Brombacher F. Exposure to the fish parasite Anisakis causes allergic airway hyperreactivity and dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 117:1098–1105.

22. Lin AH, Florvaag E, Van Do T, Johansson SG, Levsen A, Vaali K. IgE sensitization to the fish parasite Anisakis simplex in a Norwegian population: a pilot study. Scand J Immunol. 2012; 75:431–435.

23. Kim J, Jo JO, Choi SH, Cho MK, Yu HS, Cha HJ, Ock M. Seroprevalence of antibodies against Anisakis simplex larvae among health-examined residents in three hospitals of southern parts of Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2011; 49:139–144.

24. AAITO-IFIACI Anisakis Consortium. Anisakis hypersensitivity in Italy: prevalence and clinical features: a multicenter study. Allergy. 2011; 66:1563–1569.

25. Mazzucco W, Lacca G, Cusimano R, Provenzani A, Costa A, Di Noto AM, Massenti MF, Leto-Barone MS, Lorenzo GD, Vitale F. Prevalence of sensitization to Anisakis simplex among professionally exposed populations in Sicily. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2012; 67:91–97.

26. Puente P, Anadón AM, Rodero M, Romarís F, Ubeira FM, Cuéllar C. Anisakis simplex: the high prevalence in Madrid (Spain) and its relation with fish consumption. Exp Parasitol. 2008; 118:271–274.

27. Kim SH, Beom JW, Kim SH, Jo J, Song HJ, Lee J. A case of anaphylaxis caused by acute gastric anisakiasis. Korean J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012; 32:276–279.

28. Jurado-Palomo J, López-Serrano MC, Moneo I. Multiple acute parasitization by Anisakis simplex. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2010; 20:437–441.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download