Abstract

Purpose

There is currently no information regarding predisposing factors for chronic and recurrent rhinosinusitis (RS), although these are considered to be multifactorial in origin, and allergic diseases contribute to their pathogenesis. We evaluated the predisposing factors that may be associated with chronic and recurrent RS.

Methods

In this prospective study, we examined patients with RS younger than 13 years of age, diagnosed with RS at six tertiary referral hospitals in Korea between October and December, 2006. Demographic and clinical data related to RS were recorded and analyzed.

Results

In total, 296 patients were recruited. Acute RS was the most frequent type: 56.4% of the patients had acute RS. The prevalences of other types of RS, in descending order, were chronic RS (18.9%), subacute RS (13.2%), and recurrent RS (11.5%). Factors associated with recurrent RS were similar to those of chronic RS. Patients with chronic and recurrent RS were significantly older than those with acute and subacute RS. The prevalences of allergic rhinitis, atopy, and asthma were significantly higher in patients with chronic and recurrent RS than those with acute and subacute RS.

Rhinosinusitis (RS) is characterized by inflammation of the nasal mucosa and paranasal sinuses and is one of the most commonly diagnosed diseases. RS can be further classified into four distinct categories. Acute RS is when symptoms are resolved within 4 weeks. Subacute RS lasts 4-8 weeks with a more insidious onset and is often referred to as "unresolved acute RS." Chronic RS is defined as persistent sinus inflammation that lasts longer than 8 weeks. Recurrent RS is defined as having three or more episodes of acute sinusitis within 1 year.1

Children typically suffer 6-8 upper respiratory infections per year, in which 5%-13% of cases are complicated by a secondary bacterial RS, whereas viruses play a more limited role in chronic or recurrent RS.2,3 Although it is assumed that inadequate treatment may lead to chronic RS and that the best way to prevent the recurrence or chronicity of RS is to treat the acute sinusitis appropriately, the role of bacterial infection and the relevance of antibiotic therapy remain controversial. Also, whether acute RS in fact progresses to chronic RS is unknown.4

Patients with recurrent RS or chronic RS are commonly evaluated for the presence of underlying conditions, such as allergies, immunodeficiency, ciliary dysfunction, and gastroesophageal reflux (GER), and anatomical abnormalities, but previous studies have focused only on patients with chronic RS.1,5,6 The contribution of allergic diseases, including allergic rhinitis and asthma, to the pathogenesis of chronic RS has long been studied but the issue remains unsettled in children,1,6-10 whereas the role of allergies in RS in adults is known.11,12

Information regarding the frequency distribution of and factors associated with the different types of RS may offer practical insights into the pathophysiology of chronic and recurrent RS and may help to identify appropriate treatment options. To better understand the pathogenesis of RS in children, we compared children with distinct RS conditions to evaluate predisposing factors that may be associated with chronic and recurrent RS.

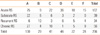

This prospective study examined RS patients younger than 15 years of age, who presented with RS at six tertiary referral hospitals in Korea between October and December, 2006. Patients were evaluated by pediatricians who practiced in the field of respiratory diseases, allergy, and immunology at their respective hospitals (A, Cha Hospital; B, Inje University Sanggye Paik Hospital; C, Eulji University Hospital; D, The Catholic University of Korea Bucheon St. Mary's Hospital; E, Konkuk University Hospital; and F, Kyung Hee University Hospital; Table 1).

The study was approved by the local ethical commissions at each hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient. All patients were evaluated according to the diagnostic criteria developed by the consensus reports of the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters1 and the Subcommittee on the Management of Sinusitis and Committee on Quality Improvement.13

RS was defined as when two or more of the following symptoms were present: anterior and/or posterior mucopurulent drainage; nasal obstruction or blockage; facial pain, pressure, and/or dullness; and reduction of sense of smell.1,6 Acute RS was defined as having either a purulent nasal discharge that lasted at least 3-4 consecutive days with a temperature of at least 39℃, or a nasal or postnasal discharge or a daytime cough that lasted longer than 14 days and less than 4 weeks. Subacute RS was considered as symptoms lasting 4-8 weeks. Chronic RS was defined as having episodes of inflammation lasting for more than 8 weeks with persistent residual respiratory symptoms, such as coughing, rhinorrhea, or nasal obstruction. Recurrent RS consists of three or more episodes of acute sinusitis within 1 year.

Demographic and clinical data were recorded and assessed, including whether the patients had siblings, attended a daycare center, their familial allergy history (doctor-diagnosed allergic disease in their parents and/or siblings), any doctor-diagnosed allergic diseases (allergic rhinitis, asthma, atopic dermatitis), GER, immunodeficiency, ciliary dyskinesia, bronchiectasis, adenoid hypertrophy, and anatomical problems of the nose. Allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and asthma were diagnosed based on the history of the patients and physical examination. Allergic rhinitis was defined as troublesome sneezing, nasal pruritus, blocked or runny nose associated with dust or pets, and eye involvement without common cold or flu. Asthma was defined based on typical asthmatic symptoms, use of asthmatic medication, and past medical history. The patients were evaluated for the presence of allergic sensitization using skin-prick tests and/or specific IgE assessment (ImmunoCAP®, Phadia AB, Uppsala, Sweden or MAST-CLA, Hitachi Chemical Diagnostics, Mountain View, CA, USA). A level of ≥0.35 IU/mL by ImmunoCAP or ≥class 2 by MAST-CLA was considered positive, as specified by the manufacturers. Allergic skin-prick testing was performed with nine common aeroallergens: Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinae, cockroach, dog, cat, mold mix, grass mix, tree mix, and weed mix (Allergopharma, Reinbek, Germany). A test response was considered positive if the prick test resulted in a wheal with a mean diameter (mean of maximum and 90° midpoint diameters) that was at least 3 mm greater than that produced by a saline control. Atopy was defined as being sensitized with one or more inhalant allergens in the above tests.

A lateral X-ray view of the skull was checked for adenoid hypertrophy when deemed necessary. Adenoid hypertrophy was evaluated with Fujioka's adenoid-nasopharyngeal (AN) ratio and was defined as AN ratios more than 2 standard deviations above the mean value derived from the appropriate age group.14 Gastrointestinal diseases, ciliary dyskinesia, bronchiectasis, or anatomical problems of the nose were diagnosed by performing confirmative tests, including radiological tests, respiratory mucosal biopsies, and 24 hour pH monitoring, when necessary.

To determine the predisposing factors that may be associated with chronic and recurrent RS, all patients were classified as acute, subacute, chronic, or recurrent RS, according to the definitions above. Demographic variables were compared to the clinical data. The statistical significance of differences between the four groups was evaluated using one-way ANOVA or the chi-square test. Then logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify any independent predictive factors for chronic and recurrent RS. Statistically significant and potentially important variables were included in the regression model. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. The SPSS software was used (ver. 17.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

In total, 296 patients were recruited. The number of enrolled patients from each hospital varied, and the relative distribution of acute, subacute, recurrent, and chronic RS was likely dependent on the individual hospitals (P<0.05). Acute RS was the most frequently diagnosed type of RS, documented in 56.4% of the study participants. The prevalences of the other types of RS, in descending order, were chronic RS (18.9%), subacute RS (13.2%), and recurrent RS (11.5%; Table 1).

The mean age of the enrolled patients was 4.3 (range, 1-13) years of age, and 176 males were recruited. The proportion of subjects who underwent radiographic imaging of the adenoid, an allergy test for specific IgE, or an immunologic evaluation, after evaluations at their individual hospitals, were 63 (21.3%), 99 (33.4%), and 8 (2.4%), respectively. Among 34 patients with acute or subacute RS who were tested with specific IgE, 8 were sensitized while 44 among 65 patients with chronic or recurrent RS were sensitized.

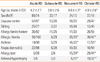

Patients with chronic RS showed a tendency for adenoid hypertrophy (59.4%; 19/32), while recurrent RS, acute RS, and subacute RS showed frequencies of 27.3% (6/22), 16.7% (1/6), and zero (0/3), respectively. Because these tests were performed almost exclusively on patients with chronic and recurrent RS, the results provide only a limited amount of information. None of the cases needed an evaluation for ciliary dysfunction, bronchiectasis, or GER. The clinical characteristics of acute/subacute RS and chronic/recurrent RS are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences according to gender, whether one had siblings, family history of allergies, or whether one had attended a daycare center. Patients with chronic or recurrent RS were significantly older than those with acute or subacute RS. The prevalences of allergic rhinitis, atopy, and asthma were significantly higher in chronic or recurrent RS patients than in those with acute and subacute RS. Predisposing factors were similar between chronic and recurrent RS. When all of the patients were classified into one of two groups, the acute/subacute or the chronic/recurrent RS groups, there was no difference regarding clinical variables.

Logistic regression was performed to determine which risk factors remained significant for chronic/recurrent RS after controlling for other variables, including the hospital visited, age, allergic rhinitis, atopy, and asthma. Adenoid hypertrophy could not be adjusted in regression analysis because there were too few cases with acute and subacute RS. The odds of having chronic/recurrent RS were significantly higher among older children with atopy (Table 3).

In the present study, the categorical frequency of doctor-diagnosed RS and the predisposing factors for recurrent RS were similar to those of chronic RS. Age, allergic rhinitis, atopy, and asthma seem to be predisposing factors for chronic and recurrent RS. Adenoid hypertrophy was most prevalent in chronic RS.

This is the first report of the prevalence of each type of RS among preschool and school-age children in Korea. Acute RS was the most common type of RS, and the number of chronic RS patients was approximately one-third the number of acute RS patients, while the proportions of subacute and recurrent RS patients were relatively small. The study population consisted of subjects who had visited the pediatric outpatient clinic at one of six tertiary referral hospitals. Our classification of chronic RS was based on having symptoms for 8 weeks, while other guidelines or expert panels have defined chronic RS as having symptoms for longer than 12 weeks.1 Thus, our classification permits the possibility of overestimating the prevalence of chronic RS, and the proportion of chronic RS may be lower in primary care practice.

There is currently no information on the prevalence and the predisposing factors of recurrent RS in children. In the present study, patients who were susceptible to recurrent RS showed clinical characteristics that were similar to those of chronic RS, indicating that recurrent RS might be within the spectrum of chronic RS. In contrast, recurrent RS in adults may be considered a distinct form of chronic RS.5,15

Patients with chronic and recurrent RS were older than those with acute and subacute RS. We also found that children who were 4-6 years of age were not only the largest group in the entire study population, but also had the highest prevalence of chronic/recurrent RS. This finding is consistent with previous reports that children with chronic sinus disease were somewhat older than those with acute infections that respond to a single course of antibiotic treatment (4-7 vs. 1-5 years).7,16 Although upper viral respiratory infections precede subsequent bacterial invasion and are common predisposing factors for RS,2,3,7 there was no difference in other factors associated with recurrent upper respiratory infections, such as daycare center attendance or having siblings. Thus, we could not explain the pathogenesis of chronic and recurrent RS by infections. Studies based on the International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Children (ISAAC) found the prevalences of current allergic rhinitis and allergic rhinitis treated within the past 12 months to be 24.2% and 29.5%, respectively, in elementary school children in Korea.17 The prevalence of the latter was 11.1%.18 Allergic rhinitis was found in 35.1% of our patients with acute/subacute RS and was more prevalent than would be expected in the general population of the same age in Korea. Nevertheless, this relationship between allergic rhinitis and RS was more significant in children with chronic and recurrent RS than children who had acute or subacute RS. This is consistent with previous results showing that allergic rhinitis or allergic sensitization was found in 36%-60% of patients with chronic RS.1,8

The prevalence of reported asthma in elementary school children in Korea is 9.4%.19 In our results, while the prevalence of asthma was 15.9% among children diagnosed with acute/subacute RS, 37.5% of those with chronic/recurrent RS and 62.3% of children with asthma had chronic and recurrent RS. This association between asthma and RS has been known for many years. As many as 80%-90% of children and adolescents with asthma have nasal symptoms, and half of all patients with asthma have radiographic evidence of RS. Several studies have shown that 40%-60% of children with asthma have chronic RS.8,20,21 Our results are consistent with these previous reports.

After controlling for allergic rhinitis, atopy, asthma, and hospital, we found allergen sensitization to be the most significant independent factor for chronic/recurrent RS. Although several studies and guidelines would suggest a correlation between allergic rhinitis or allergic sensitization and chronic RS, several studies have failed to confirm a consistent relationship.9-11 Among them, two studies reported results that contrast with our findings. The differences are likely due to their method of selecting the study population, which consisted of those with chronic upper respiratory symptoms or signs. After dividing the patients into two groups, based on abnormalities on computed tomography, they compared the groups to show that there were no differences in allergic sensitization.9,10 Another study reported no difference in allergic sensitization between children with chronic RS and a normal population, demonstrating that they were almost all sensitized to seasonal allergens.11 In the present study, chronic and recurrent RS was based on clinical symptoms and signs, and allergic status was not evaluated in all patients because some were referred to the study and had already received a diagnosis from their primary physician. Patients with non-allergic and persistent rhinitis might have been included in the study, potentially biasing our results; on the other hand, that more than 60%-80% of children with allergic rhinitis in Korea are sensitized to house dust mites should also be considered.22,23 Several studies have shown that perennial allergies seem to play a significant role in the development of recurrent or chronic RS. Huang24 reported that there was a much higher prevalence of RS in children with perennial allergic rhinitis to mold and/or mites. Several other studies have demonstrated that, in adults, perennial allergic rhinitis to mites, for example, is associated with chronic RS. Thus, it has been concluded that perennial allergies contribute to the development of chronic RS, providing further evidence that dust mites are associated with chronic insults in the sinonasal mucosa.25,26 Persistent allergic inflammation likely causes nasal congestion and swelling of the mucous membrane, which can obstruct or impede normal sinus drainage. All of these factors seem to potentiate chronic/recurrent RS.

Our study has some limitations. First, allergy testing for specific IgE was not performed to determine whether a patient had allergic rhinitis; instead, we relied on patient history and/or medical records provided by the primary physician. Thus, the prevalence of allergic rhinitis and asthma may have been overestimated. Second, patients that were recruited at tertiary care centers in Korea may not represent the general population of the disease groups. Third, adenoid hypertrophy seemed to be an important factor; however, because minimal evaluations of patients with acute and subacute RS were performed, a comparison with chronic/recurrent RS was not possible in this study. Finally, an objective evaluation of other potentially confounding factors, such as GER, ciliary dyskinesia, or immune deficiency, was not performed properly. Prospective studies that include the use of tests that are specific for IgE are needed to evaluate other confounding factors.

In conclusion, this study showed that age, atopy, allergic rhinitis, and asthma seem to be predisposing factors for chronic and recurrent RS. The association between atopy and chronic/recurrent RS suggests a possible causal link, when compared to acute/subacute RS. Specific evaluation for allergic diseases should be considered when managing chronic or recurrent sinusitis.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Slavin RG, Spector SL, Bernstein IL, Kaliner MA, Kennedy DW, Virant FS, Wald ER, Khan DA, Blessing-Moore J, Lang DM, Nicklas RA, Oppenheimer JJ, Portnoy JM, Schuller DE, Tilles SA, Borish L, Nathan RA, Smart BA, Vandewalker ML. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. The diagnosis and management of sinusitis: a practice parameter update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005. 116:S13–S47.

2. Sande MA, Gwaltney JM. Acute community-acquired bacterial sinusitis: continuing challenges and current management. Clin Infect Dis. 2004. 39:Suppl 3. S151–S158.

3. Aitken M, Taylor JA. Prevalence of clinical sinusitis in young children followed up by primary care pediatricians. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998. 152:244–248.

4. Marseglia GL, Castellazzi AM, Licari A, Marseglia A, Leone M, Pagella F, Ciprandi G, Klersy C. Inflammation of paranasal sinuses: the clinical pattern is age-dependent. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007. 18:Suppl 18. 10–12.

5. Alho OP. Viral infections and susceptibility to recurrent sinusitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2005. 5:477–481.

6. Fokkens W, Lund V, Mullol J. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps group. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2007. Rhinol Suppl. 2007. 1–136.

7. Chan KH, Winslow CP, Levin MJ, Abzug MJ, Shira JE, Liu AH, Simoes EA, Strain JD, Stool SE. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of chronic sinusitis in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999. 120:328–334.

8. Lombardi E, Stein RT, Wright AL, Morgan WJ, Martinez FD. The relation between physician-diagnosed sinusitis, asthma, and skin test reactivity to allergens in 8-year-old children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1996. 22:141–146.

9. Iwens P, Clement PA. Sinusitis in allergic patients. Rhinology. 1994. 32:65–67.

10. Nguyen KL, Corbett ML, Garcia DP, Eberly SM, Massey EN, Le HT, Shearer LT, Karibo JM, Pence HL. Chronic sinusitis among pediatric patients with chronic respiratory complaints. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993. 92:824–830.

11. Leo G, Piacentini E, Incorvaia C, Consonni D, Frati F. Chronic sinusitis and atopy: a cross-sectional study. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006. 38:361–363.

12. Steinke JW, Borish L. The role of allergy in chronic rhinosinusitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004. 24:45–57.

13. American Academy of Pediatrics. Subcommittee on Management of Sinusitis and Committee on Quality Improvement. Clinical practice guideline: management of sinusitis. Pediatrics. 2001. 108:798–808.

14. Fujioka M, Young LW, Girdany BR. Radiographic evaluation of adenoidal size in children: adenoidal-nasopharyngeal ratio. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979. 133:401–404.

15. Bhattacharyya N, Lee KH. Chronic recurrent rhinosinusitis: disease severity and clinical characterization. Laryngoscope. 2005. 115:306–310.

16. Steele RW. Chronic sinusitis in children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2005. 44:465–471.

17. Kwon JW, Seo JH, Yu J, Kim BJ, Kim HB, Lee SY, Kim WK, Kim KW, Ji HM, Kim KE, Shin YJ, Kim MH, Kim H, Hong SJ. Relationship between the prevalence of allergic rhinitis and allergen sensitization in children of Songpa area, Seoul. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 2011. 21:47–55.

18. Nam SY, Yoon HS, Kim WK. Prevalence of allergic disease in kindergarten age children in Korea. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 2005. 15:439–445.

19. Hong SJ, Ahn KM, Lee SY, Kim KE. The prevalences of asthma and allergic diseases in Korean children. Korean J Pediatr. 2008. 51:343–350.

20. Freudenberger T, Grizzanti JN, Rosenstreich DL. Natural immunity to dust mites in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1988. 82:855–862.

21. Corren J, Rachelefsky GS. Interrelationship between sinusitis and asthma. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 1994. 14:171–183.

22. Kim YJ, Han JE, Kang IJ. Change of inhalant allergen sensitization in children with allergic respiratory diseases during recent 10 years. Korean J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004. 24:241–246.

23. Cho SH, Kim YK, Sohn JW, Kim WK, Lee SR, Park JK, Min KU, Ha MN, Ahn YO, Jee YK, Lee SI, Kim YY. Prevalence of chronic rhinitis in Korean children and adolescents. J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999. 19:452–458.

24. Huang SW. The risk of sinusitis in children with allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2000. 21:85–88.

25. Gutman M, Torres A, Keen KJ, Houser SM. Prevalence of allergy in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004. 130:545–552.

26. Berrettini S, Carabelli A, Sellari-Franceschini S, Bruschini L, Abruzzese A, Quartieri F, Sconosciuto F. Perennial allergic rhinitis and chronic sinusitis: correlation with rhinologic risk factors. Allergy. 1999. 54:242–248.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download