Abstract

Objectives

Premature ovarian failure (POF) is a syndrome defined as the cessation of ovarian function before the age of 40 years that is characterized by amenorrhoea associated with elevated gonadotropin levels. The aim of this study was to compare clinical manifestation of primary amenorrhea and secondary amenorrhea group.

Methods

This study was designed as a retrospective multicenter study of 262 women with premature ovarian failure. Sixty eight women with primary amenorrhea and 194 women with secondary amenorrhea were evaluated and hormonal level, lipid profile, bone mineral density, and pregnancy rates were compared.

Results

The estradiol level was markedly lower in primary amenorrhea than secondary amenorrhea. The pregnancy rate of 43.3% before the diagnosis in secondary amenorrhea was markedly higher than the rate of 0% in primary amenorrhea. The pregnancy rates after treatment was 5.9% in primary amenorrhea, but 1.0% after diagnosis and 2.8% after treatment in secondary amenorrhea. The pregnancy rate after hormonal treatment was 3.7% in total, 8.3% in primary amenorrhea, and 2.8% in secondary amenorrhea. In nine cases of pregnancy, seven cases were after estrogen-progestin (EP), one case was after clomiphene citrate and one case was after EP/human menopausal gonodotropin (hMG). And In nine cases of pregnancy, six cases resulted from oocyte donation. The prevalence of osteopenia/osteoporosis was markedly higher in primary amenorrhea than in secondary amenorrhea.

Conclusion

Premature ovarian failure has negative influences on the physical and psychological health of young patients. Effective management should include earlier diagnosis and intensive medical intervention to relieve symptoms of estrogen deficiency and to treat long-term disease such as osteoporosis and in assisted pregnancy by oocyte donation.

Figures and Tables

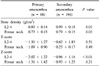

Table 2

Comparison of lipid profile and thyroid hormone level between primary and secondary amenorrhea

References

1. Nelson LM. Clinical practice. Primary ovarian insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009. 360:606–614.

2. Panay N, Kalu E. Management of premature ovarian failure. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009. 23:129–140.

3. Nippita TA, Baber RJ. Premature ovarian failure: a review. Climacteric. 2007. 10:11–22.

4. Kalu E, Panay N. Spontaneous premature ovarian failure: management challenges. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008. 24:273–279.

5. Davis SR. Premature ovarian failure. Maturitas. 1996. 23:1–8.

6. Kalantaridou SN, Nelson LM. Premature ovarian failure is not premature menopause. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000. 900:393–402.

7. Rebar RW. Premature ovarian failure. Obstet Gynecol. 2009. 113:1355–1363.

8. Lee JY, Chung HW. Premature ovarian failure. J Korean Soc Menopause. 2009. 15:79–86.

9. Kim JG, Park MC, Kim SH, Choi YM, Shin CJ, Moon SY, et al. A study on response to treatment and predictability of pregnancy in premature ovarian failure. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1993. 36:2208–2213.

10. Frankfurter D. A new paradigm for studying and treating primary ovarian insufficiency: the community of practice. Fertil Steril. 2011. 95:1899–1900.

11. Meczekalski B, Podfigurna-Stopa A, Genazzani AR. Hypoestrogenism in young women and its influence on bone mass density. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010. 26:652–657.

12. Han MS, Hwang TY. Comparison of bone mineral density in premature ovarian failure patients and spontaneous menopausal women. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2000. 43:1979–1982.

13. Gallagher JC. Effect of early menopause on bone mineral density and fractures. Menopause. 2007. 14:567–571.

14. Amarante F, Vilodre LC, Maturana MA, Spritzer PM. Women with primary ovarian insufficiency have lower bone mineral density. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2011. 44:78–83.

15. Metka M, Holzer G, Heytmanek G, Huber J. Hypergonadotropic hypogonadic amenorrhea (World Health Organization III) and osteoporosis. Fertil Steril. 1992. 57:37–41.

16. Shuster LT, Rhodes DJ, Gostout BS, Grossardt BR, Rocca WA. Premature menopause or early menopause: long-term health consequences. Maturitas. 2010. 65:161–166.

17. Rivera CM, Grossardt BR, Rhodes DJ, Brown RD Jr, Roger VL, Melton LJ 3rd, et al. Increased cardiovascular mortality after early bilateral oophorectomy. Menopause. 2009. 16:15–23.

18. Rocca WA, Shuster LT, Grossardt BR, Maraganore DM, Gostout BS, Geda YE, et al. Long-term effects of bilateral oophorectomy on brain aging: unanswered questions from the Mayo Clinic Cohort Study of Oophorectomy and Aging. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2009. 5:39–48.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download