Medical institutions have recently been faced with the task of searching for innovative strategies that can be implemented to achieve high-quality medical services and efficient management systems. Although cutting-edge medical equipment, the launch of specialized centers, and pleasant convenient facilities are important, acquiring and managing competitive, outstanding human resources is the most essential factor for strengthening the international competitiveness of medical institutions (Kim, 2010). The nursing sector has also established as its main business goals the specialization of nurses' roles, a requirement for multi-functional roles, and acquisition of low-cost, high-efficiency labor. As part of the effort to achieve such goals, nurses have taken an interest in the clinical ladder system (Park, 1998).

As a system that differentiates, acknowledges, and compensates nurses according to their clinical experiences, educational background, and nursing capabilities, the clinical ladder system for nurses can be viewed as a system that connects human resource development with personnel management within the nurse organization. The clinical ladder system for nurses was introduced to enhance the system of delivering nursing care, providing high-quality service, retaining nursing employees, and fostering clinical experts (Kwon, Sung, Park, Yu, & Kim, 2007) Many precedent studies have reported that the application of the clinical ladder system increases job satisfaction for nurses (Bjork, Samdal, Hansen, Torstad, & Hamilton, 2007; Drenkard & Swartwout, 2005; Goodrich & Ward, 2004; Hall, Waddell, Donner, & Wheeler, 2004; Hsu, Chen, Lee, Chen, & Lai, 2005), enhances retention, decreases absenteeism (Bjork et al., 2007; Drenkard & Swartwout, 2005), boosts self-efficacy and organizational commitment (Hall et al., 2004), develops the professionalism of nurses, fosters autonomy (Bjork et al., 2007; Goodrich & Ward, 2004), and improves nursing capabilities (Goodrich & Ward, 2004; Hsu et al., 2005). However, it is difficult to find studies that identify correlations between the clinical ladder system and psychosocial effects such as empowerment and professional self-concept.

Professional self-concept can be defined as one's mental perception of oneself as a professional (Geiger & Davit, 1988). In particular, a nurses' professional self-concept refers to their feelings and opinions regarding their tasks as professional nurses (Arthur, 1992). In order for nurses to carry out their tasks harmoniously with other professionals in medical worksites where various professions co-exist, it is important that they possess a professional self-concept that can equal that of other professions (Sohng & Nho, 1996). Precedent studies have reported that the professional self-concept of nurses is enhanced through having a certain amount of clinical experience, receiving creative and continuous education, having role models that display professional thinking and behavior, being provided resources, and investing individual time and effort (Cowin, Jonson, Craven, & Marsh, 2008; Geiger & Davit, 1988; Leddy & Pepper, 1985; Strasen, 1989; Choi & Park, 2009). These experiences can be obtained by continuously carrying out educational tasks for enhancing work ability through participation in the clinical ladder system.

Empowerment is a method that triggers organizational development through the autonomous actions of organization members. It refers to the pursuit of individual growth through improving activeness, autonomy, and creativity to maximize individual abilities. In a nurse organization, empowerment allows nurses to independently improve their own capabilities in order to expand their power within the organization and bring about positive changes in the attitudes and behavior of organization members (Kwon, Yom, Kwon, & Lee, 2007). Studies have reported such changes to be effective in improving job satisfaction (Park & Park, 2008), motivation (Yang, 1999), organizational commitment (Yom, 2006), and work performance (Yang, 1999), as well as in reducing turnover intention (Park & Park, 2008) and work stress (Hur, 2009).

Although clinical sites in Korea are increasingly recognizing the need for the clinical ladder system and are optimistic about its potential, the system has been introduced in only a few hospitals. Thus, there are very few studies that have measured the effects of the clinical ladder system after its implementation or investigated perceptions of the system among clinical nurses. The establishment of a more elaborate model requires an assessment of nurses and others who have participated in institutions that have applied the system, as well as continuous interest and feedback. Therefore, in this study the perception of Korean nurses regarding the clinical ladder system was analyzed according to their clinical career stage and the relationship between the perceptions of the system, professional self-concept, and empowerment was examined; the results provide evidence for improving the clinical ladder system for nurses and contributing to human resource management by exploring measures for enhancing professional self-concept and empowerment.

A descriptive correlational design was used in this study to identify nurses' perception of clinical ladder system and explore the relationship among perception of clinical ladder system, professional self-concept and empowerment.

The research was approved by the institutional review board of Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea (approval no. 2010-1002). The participants in this study were nurses working in intensive care units, operating rooms and emergency rooms in a high-level general hospital in Seoul. A sample size above 135 was needed for this study by a test power of .80, a significant level of .05, an effect size of .15 using G*power version 3.1.3 program. Data were collected from April 17 to April 23, 2012 using a structured questionnaire, of which 162 were distributed, and 155 returned (95.6% response rate). But, 2 questionnaires had insufficient responses or were not complete. Therefore, the final sample included 153 questionnaires. Each participant signed a written consent after receiving information about the study goals, data collection, and confidentiality. They were told that the data collection process could be stopped at any time with no penalty.

To measure perceptions of the clinical ladder system, the researcher revised and supplemented a tool for measuring such perceptions developed by Park and Lee (2010) based on Nelson and Cook's (2008) tool for assessing the clinical ladder system of nurses and a tool developed by Riley, Rolband, James, and Norton (2009) for measuring the perception of the clinical ladder system. The validity of the content was confirmed after the content was reviewed by 2 professors and 1 doctor of nursing. The tool is composed of 24 items: 6 items related to the general understanding of the clinical ladder system, 4 items related to the perception of participating in professional activities, 10 items related to the expected effects of the clinical ladder system, and 4 items related to the experience of moving up the ladder. Each item is assessed using a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from "strongly disagree" (1) to "strongly agree" (4). Higher scores indicate a more positive perception regarding the clinical ladder system. Cronbach's α was .92 in the original study and .93 in this study.

To measure professional self-concept for this study a tool created by Sohng and Noh (1996) was used after adaption, revision, and supplementation of the Professional Self-Concept of Nurse Instrument (PSCNI) developed by Arthur (1992). The validity of the content was confirmed after review by 2 professors and 1 doctor of nursing. This tool is composed of 27 items, which are divided into 3 sub-domains: 15 items related to professional practice (flexibility, leadership, and skills), 8 items related to satisfaction, and 4 items related to communication. Each item is assessed using a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from "strongly disagree" (1) to "strongly agree" (4). Negatively worded items (7 items: 9, 12, 13, 18, 21, 23, 25) are inversely processed, with a higher score indicating higher professional self-concept. Cronbach's α was .85 in the original study and .87 in this study.

To measure empowerment in this study, an appropriately revised and supplemented a tool created by Yang (1999) was used. This tool was developed after revising and adapting the Condition of Work Effectiveness Questionnaires (CWEQ), a tool developed by Chandler (1986) based on Kanter's (1979) "Theory of Organizational Empowerment Structure." The validity of the content was confirmed after review by 2 professors and 1 doctor of nursing. This tool is composed of 28 items: 9 items related to opportunity, 8 items related to information, 8 items related to support, and 3 items related to resources. Each item is assessed according to a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from "strongly disagree" (1) to "strongly agree" (4). Higher scores indicate a higher level of empowerment. Cronbach's α was .69~ .98 in the original study and .88 in this study.

Data was analyzed using the SPSS WIN program 18.0. Descriptive statistics were used to identify general characteristics of the participants, perception of clinical ladder system, professional self-concept and empowerment. ANOVA between groups was used to compare differences in the scores of perception of the clinical ladder system, professional self-concept and empowerment according to nurses' clinical career stage. Scheffé test was conducted as a post-comparison test. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to determine the relationship between perception of clinical ladder system, professional self-concept and empowerment. Multiple Linear Regression analyses were performed to determine the predictors of professional self-concept and empowerment.

The age of the nurses ranged from 23 to 43, with nurses between 26 and 30 years of age accounting for 50.3%. The average age was 28.7. Women accounted for 94.8% of participants, and 74.5% of nurses were not married, triple the number who were married. Seventeen nurses had graduated from 3-year nursing schools, 124, from 4-year universities, and 12 had master's degrees; thus, the majority were 4-year university graduates. In terms of work experience, 48.4% had 1-5 years work experience, whereas 28.8% had 5-10 years and 56.2% had worked for 1-5 years in their currently affiliated department. Nurses currently working in an intensive care unit accounted for 54.2%, followed by the operating room (31.4%) and emergency room (14.4%).

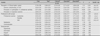

Specialist 2 nurses presented more positive perceptions of the clinical ladder system than new nurses, general nurses, and specialist 1 nurses. For general understanding, one of the sub-domains of the clinical ladder system, specialist 2 nurses presented the highest level of understanding, followed by general nurses and specialist 1 nurses, with new nurses ranking lowest. The ranking among the nurses was the same for perception of participating in professional activities, the highest for specialist 2 nurses, followed by general nurses and specialist 1 nurses, and then new nurses. The effects of the clinical ladder system were expected to differ according to clinical experience, but Scheffé method showed the existing difference was not significant (Table 1).

Specialist 2 nurses presented the highest professional self-concept*, followed by general nurses, with new nurses ranking lowest. For professional practice, a sub-domain of professional self-concept, specialist 2 nurses and specialist 1 nurses presented higher leadership professional practice than new nurses. On the other hand, flexibility was highest in specialist 2 nurses, followed by general nurses and new nurses respectively. In the case of skills, specialist 2 nurses ranked highest, followed by specialist 1 nurses and general nurses, with new nurses ranking lowest.

There was no significant difference in empowerment according to clinical career stage.

The correlation between the perception of the clinical ladder system and professional self-concept was positive (+) and statistically significant. Thus, a more positive perception of the clinical ladder system signified a higher professional self-concept. The professional self-concept sub-domain skills, a sub-domain of professional practice, presented the highest correlation with the perception of the clinical ladder system. Significant correlations also existed with leadership and flexibility, other sub-domains of professional practice, as well as with satisfaction and communication (Table 2).

The perception of the clinical ladder system presented a statistically significant positive correlation with empowerment; indicating that more positive of perception of the system signified higher empowerment. The empowerment domain presenting the highest correlation with perception of the clinical ladder system was opportunity. Significant correlations also existed with information, support and resources in that order.

In examining survey results, including perceptions of the clinical ladder system, clinical career stage, demographic characteristics, and job-related characteristics, the following variables were found to be statistically significant factors influencing professional self-concept: general understanding of the clinical ladder system, expected effects of the clinical ladder system, having a master's degree, and being general, specialist 1 or 2 nurses in one's clinical career stage. The explanatory power of this model was 42% (Table 3).

The survey results showed that the following variables had statistical significance as factors influencing of empowerment: general understanding of the clinical ladder system, perception of participating in professional activities, expected effects of the clinical ladder system, and being specialist 1 and 2 nurses in one's clinical career stage. The explanatory power of this model was 42%.

The perception of the clinical ladder system according to clinical career stage was significantly higher in specialist 2 nurses when compared with specialist 1 nurses, general nurses, and new nurses. However, the average perception of general nurses was higher than that of specialist 1 nurses signifying that even as nurses participate in the clinical ladder system and gain more clinical experience, it does not naturally increase their perception of the clinical ladder system. Also, this shows that additional efforts must be made to enhance nurses' perceptions. Precedent studies have reported that the organizational dimension has been largely influential in preventing the extensive development of nursing capabilities and affecting the perceptions of nurses. Jang (2000) showed that as nurses were not given differentiated roles or functions by the nurse organization even with increased work experience, so they did not feel the need to develop their roles or expertise, although they possessed the desire to achieve personal development. Thus, it is necessary to conduct a detailed diagnosis on how the currently implemented clinical ladder system for nurses satisfies nurses' needs for developing expertise and whether they are being appropriately recognized through internal and external compensation.

Regarding general understanding of the clinical ladder system according to clinical career stage, the highest level of understanding was shown by specialist 2 nurses, followed by specialist 1 nurses and general nurses, with new nurses ranking lowest. This signifies that general understanding of the system increases with higher clinical career stage. Carryer, Russell, and Budge (2007) emphasized the necessity of increasing knowledge and providing education about the clinical ladder system, as nurses tend to develop a more positive attitude when they become more knowledgeable about the program. Similarly, Nelson and Cook (2008) reported that participating in the clinical ladder system is related to having knowledge about the relevant system, indicating that a lack of information acts as a barrier to participation. Kim (2010) also stated that to achieve a successful clinical ladder system, it is necessary to organize a support system that can help nurses understand the clinical ladder system through education, connect nurses with mentors through personal consulting, and continuously improve and complement the system through regular satisfaction surveys and interviews. Thus, to establish the clinical ladder system, it is of primary importance to emphasize the enhancement of nurses' general understanding of the system through systematic educational programs. In addition, it is also essential to provide continuous education in institutions that have already implemented the clinical ladder system in order to improve nurses' understanding of it. In particular, the study results showed there was a lower general understanding of the system among new nurses who will participate in the clinical ladder system in the future, and therefore it is important to provide information and carry out educational programs and promotional measures for enhancing the new nurses' understanding of the clinical ladder system.

Regarding the perception of participating in professional activities according to clinical career stage, specialist 2 nurses reported the most positive perception, followed by specialist 1 nurses and general nurses, with new nurses ranking lowest. This result signifies that the perception of participating in professional activities increases with higher clinical career stages. This can be understood in the same context as the results presented by Nelson and Cook (2008), who reported the following: application of the clinical ladder system led to an increase in leadership activities, quality-enhancement activities, and preceptorship activities; condition of patients of nurses who participated in leadership activities improved; and participating in the development of nurse education data stimulated nurses' growth. However, a study conducted by Riley, Rolband, James, and Norton (2009) indicated that increased overtime work due to participation in professional activities acts as a barrier to participating in the clinical ladder system. Park and Lee (2011) also reported work overload and excessive time investment as negative results of adapting to the clinical ladder system. Thus, efforts must be made to increase the positive perception of participating in professional activities. Unlike the nurse system in Korea, nurses working abroad are provided with structured guidelines for receiving compensation for participation in professional activities outside of working hours (Park & Lee, 2010). Thus, in order to naturalize the clinical ladder system in the nursing practice of Korea, it is not only important to relieve the overload experienced by nurses due to their expanded roles; it is also essential to devise organization-level measures, such as division of work and efficient time allocation (Park & Lee, 2011). In this regard, instead of creating an atmosphere that considers an increased scope of professional activities and responsibilities as merely a natural consequence of being at a higher clinical career stage, it is important to provide appropriate compensation for nurses' participation in professional activities outside of working hours and reduce role overload in order to enhance the perception of participating in professional activities and induce active participation in the clinical ladder system.

Regarding the expected effects of the clinical ladder system according to clinical career stage, specialist 1 nurses with experience moving up the ladder showed lower expectations for the system than general nurses and new nurses without relevant experience. Riley et al. (2009) reported that nurses' perception of the effects of the clinical ladder system can serve to increase participation in the system; thus, it is necessary to analyze other factors that reduce effects expected by nurses in the process of applying the clinical ladder system. Goodrich and Ward (2004) reported that excessive time consumption, the requirement of paperwork, and inappropriate compensation when compared with responsibilities act as barriers to participating in the clinical ladder system, thus indicating the need for changes. In particular, job tests, submission of portfolios, interviews, and presentations carried out in the process of assessing nurses participating in the clinical ladder system increase their emotional burden and negative perception regarding the effects of the clinical ladder system. Although participation in the clinical ladder system is a process required to develop the abilities of nurses, it can also act as an obstacle that prevents nurses from actively participating in the system. In this sense, it is important to provide measures for reducing the emotional burden of nurses applying for the program. Furthermore, although few precedent studies have introduced, the clinical ladder system as a human resource management system (Kwon et al., 2007; Park, Park, & Park, 2006), it is important to consider the study by Kim (2010), who reported that the clinical ladder system must be operated as an expertise development program separate from the human resource management system in order to relieve the stress of nurses and induce voluntary motivation to boost the effects of the system.

Professional self-concept according to clinical career stage was highest among specialist 2 nurses, followed by general nurses, with new nurses ranking lowest. This result indicates that nurses have a tendency to acquire a higher professional self-concept with more advanced clinical career stage. In the case of professional practice according to clinical career stage, specialist 2 nurses presented the highest average score for all domains (leadership, flexibility, and skills), followed by specialist 1 nurses, general nurses, and new nurses. These results are due to the fact that nurses with more clinical experience can become more proficient in professional practice, thus facilitating smooth relations with other nurses. On the other hand, Jang (2000) reported that higher clinical career stage does not always signify improved nursing capabilities. In this regard, as new nurses do not naturally gain improved work ability with increased work experience, it is important to invest time and effort and provide support and good role models in order to improve the professional capabilities of new nurses.

No significant differences were found for satisfaction and communication according to clinical career stage. Although specialist 2 nurses presented the highest average score for satisfaction and communication, general nurses ranked second for satisfaction, whereas new nurses ranked second for communication. Choi and Park (2009) indicated that the reason for the low level of satisfaction seen in various research results is linked to the fact that satisfaction is a comprehensive concept for nursing jobs; although the individual ability of nurses has been improved through education, practice, and research activities, along with the recent specialization of nursing as a career, institutional factors such as work environment, administration, and organizational culture have not improved in proportion to such achievements. Thus, separate administrative or educational measures are required to motivate and improve the self-esteem of nurses. Efforts must also be made to create an organizational culture that can promote development of a positive, firm professional self-concept through occupational life. Administrative and educational support must be provided to allow experienced nurses to remain in clinical positions to display their nursing abilities, provide high-quality nursing service, and teach junior nurses, and these steps must, in turn, lead to career development.

There were no significant differences in empowerment according to the clinical career stage. Further, new nurses ranked highest in the average scores for the opportunity and resource domains, whereas specialist 2 nurses ranked highest in the information domain and general nurses ranked highest in the support domain; thus, a consistent increase in empowerment according to clinical career stage was not shown. In the case of new nurses, the average score for empowerment was highest in the opportunity domain when compared with nurses in other stages. Corresponding with the study conducted by Yang (1999), this result is attributed to the fact that new nurses are highly exposed to opportunities to participate in training programs to acquire new skills and knowledge. Specialist 1 nurses presented the lowest empowerment score with the average score for empowerment being slightly lower in the opportunity domain. This is due to the fact that, although specialist 1 nurses moved up the clinical ladder, they felt that they were given fewer opportunities to acquire and use new skills and knowledge to improve nursing capabilities. Therefore, to increase the empowerment standard of specialist 1 nurses, it is important to provide continuous educational programs to increase the specialized knowledge and skills required to carry out nursing duties.

The average empowerment score in the information domain gradually increased according to the clinical career stage from new nurse to specialist 2 nurse, although the increase was not significant. This is linked to the result of Jang (2000), who found that whereas new nurses usually focus on the given tasks and are less aware of their surroundings, but experienced nurses are able to perceive the entire situation. Their holistic understanding and analytic skill enhance their decision-making ability and thus in addition to their primary role of taking care of patients, specialist 2 nurses also possess knowledge and perception regarding the entire situation in the ward or hospital. These qualities, in turn, empower them.

The statistically significant variables influencing professional self-concept were general understanding of the clinical ladder system, expected effects of the system, having a master's degree, and the clinical career stage of general, specialist 1, and specialist 2 nurses. Thus, professional self-concept increased with a higher degree of general understanding and greater expected effects of the clinical ladder system. Furthermore, general nurses, specialist 1 nurses, and specialist 2 nurses presented a higher professional self-concept than new nurses, the reference group for clinical career stage. On the other hand, professional self-concept was higher among nurses with a master's degree than among 3-year college graduates, the reference group for academic background. This corresponds with the results of Choi and Park (2009), who found that improving one's academic background through continuous learning serves to increase professional self-concept. Furthermore, Park and Lee (2011) reported that by participating in the clinical ladder system, most nurses establish their identity as a nurse and become top specialists that can provide genuine care to patients. In addition, Cowin et al. (2008) suggested that to improve the professional self-concept of nurses, continuous educational programs must be provided to help them acquire skills and knowledge that can be used with confidence in clinical sites. Based on these results, the application of the clinical ladder system can be expected to positively affect the professional self-concept of nurses.

The statistically significant variables influencing empowerment were general understanding of the clinical ladder system, perception of participating in professional activities, expected effects of the system, and the clinical career stage of specialist 1 and 2 nurses. Thus, empowerment increases with a higher degree of general understanding of the clinical ladder system, more positive perception of participation in professional activities, and greater expected effects of the clinical ladder system. Furthermore, results showed that new nurses, the reference group for clinical career stage, presented higher levels of empowerment than specialist 1 and 2 nurses. Kwon et al. (2007) stated that nurses become empowered when they gain the opportunity and motivation to display talent and are acknowledged and supported for their competence. On the other hand, Park and Lee (2011) reported that, in the application of the clinical ladder system, the interest in and execution ability of the system displayed in organizational and nurse human resources policy acted as a positive factor and strategy in accomplishing the tasks required in the system. The study also reported that the support of preceptors and colleagues significantly helped participants to complete assessment tasks with confidence. Thus, application of the clinical ladder system provides nurses with the opportunity to develop and display their talent and positively affects empowerment in that it provides nurses with support and experience through the process.

This study demonstrated that nurses' perception of the clinical ladder system and professional self-concept increased with higher clinical career stages. Furthermore, a more positive perception of the system increased professional self-concept and empowerment. To effectively apply the clinical ladder system, it is important to make an effort to use measures that can improve nurses' understanding and expectations of the system and stimulate participation in professional activities to increase their perception of the system. In particular, information and educational programs must be continuously provided to promote understanding of the clinical ladder system among new nurses, who have presented a relatively low level of perception. Furthermore, it is important to identify the causes of negative perceptions of the clinical ladder system and the obstacles experienced in the process of participating in the system. Measures to solve these obstacles must be provided along with appropriate internal and external compensations that encourage participation in professional activities and give nurses recognition for moving up the ladder. In addition, nursing departments and medical institutions must be supported in their efforts to operate the system in a way that satisfies the nurses' expectations. Such efforts can enhance the perception of the clinical ladder system and facilitate its efficient operation, which in turn can positively affect professional self-concept and empowerment, factors that have a positive correlation with the perception of the clinical ladder system. This, in turn, will contribute to effective human resource management. Factors related to the perception of clinical ladder system, professional self-concept, and empowerment must be appropriately used by nurse administrators as the basic data for achieving effective human resource management.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Difference in Perception of Clinical Ladder System, Professional Self-concept, and Empowerment according to Clinical Career Stage (N=153)

*New Nurse = Either a new graduate nurse or a nurse who was new to the organization; †General Nurse = Nurse who successful completed the probation period and the orientation program; ‡Specialist 1 Nurse = A proficient nurse who functions independently (Application is required); §Specialist 2 Nurse = An expert nurse whose intuition and skill arise from a comprehensive knowledge base thoroughly grounded in experience (Application is required).

References

1. Arthur D. Measuring the professional self-concept of nurses: A critical review. J Adv Nurs. 1992. 17:712–719. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb01969.x.

2. Bjork IT, Hansen BS, Torstad S, Hamilton GA. Job satisfaction in a Norwegian population of nurses: A questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007. 44:747–757. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.01.002.

3. Carryer J, Russell A, Budge C. Nurses' understandings of the professional development recognition programme. Nurs Prax N Z. 2007. 23(2):5–13.

4. Chandler GE. The relationship of nursing work environment to empowerment and powerlessness. 1986. Salt Lake City: University of Utah;Unpublished doctoral dissertation.

5. Choi J, Park HJ. Professional self-concept, self-efficacy and job satisfaction of clinical nurse in schoolwork. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2009. 15:37–44.

6. Cowin LS, Jonson M, Craven RG, Marsh HW. Causal modeling of self-concept, job satisfaction, and retention of nurses. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008. 45:1449–1459. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.10.00.

7. Drenkard K, Swartwout E. Effectiveness of a clinical ladder program. J Nurs Adm. 2005. 35:502–506. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005110-200511000-00007.

8. Kettinger Geiger JW, Davit JS. Self-image and job satisfaction in varied settings. Nurs Manage. 1988. 19(12):50–56. 58

9. Goodrich CA, Ward CW. Evaluation and revision of a clinical advancement program. Medsurg Nurs. 2004. 13:391–398.

10. Hall LM, Waddell J, Donner G, Wheeler MM. Outcomes of a career planning and development program for registered nurses. Nurs Econ. 2004. 22:231–238.

11. Hsu N, Chen BT, Lee LL, Chen CH, Lai CF. The comparison of nursing competence pre- and post- implementing clinical ladder system. J Clin Nurs. 2005. 14:264–265.

12. Hur YJ. Relationship between empowerment, job stress and burnout of nurses in hemodialysis units. 2009. Daegu, Korea: Keimyung University;Unpublished master's thesis.

13. Jang KS. A study on establishment of clinical career development model of nurses. 2000. Seoul, Korea: Yonsei University;Unpublished doctoral dissertation.

14. Kanter RM. Men and women of the corporation. 1977. New York: Basic Books.

15. Kim HY. Developing and verifying validity of a clinical ladder system for operating room nurses. 2010. Gwangju, Korea: Chonnam National University;Unpublished doctoral dissertation.

16. Kwon IG, Sung YH, Park KO, Yu OS, Kim MA. A study on the clinical ladder system model for hospital nurses. Clin Nurs Res. 2007. 13:7–23.

17. Kwon SB, Yom YH, Kwon EK, Lee YY. The empowerment experience of hospital nurses using focus groups. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2007. 13:445–454.

18. Leddy S, Pepper JM. Conceptual bases of professional nursing. 1985. Philadelphia: Lippincott Co.

19. Nelson JM, Cook PF. Evaluation of a career ladder program in an ambulatory care environment. Nurs Econ. 2008. 26:353–360.

20. Park JS, Park BN. The influence of empowerment on job satisfaction, task performance and turnover intention by hospital nurses. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2008. 14:150–158.

21. Park KO. The concept and necessity of clinical nurse career ladder system, the seminar for the establishment of concept of clinical nurse career ladder system. 1998. Seoul, Korea: Korean Clinical Nursing Association.

22. Park KO, Lee YY. Career ladder system perceived by nurses. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2010. 16:314–325.

23. Park KO, Lee MS. Nurses' experience of career ladder programs in a general hospital. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2011. 41:581–592.

24. Park SH, Park KO, Park SA. A development of career ladder program. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2006. 12:624–632.

25. Riley JK, Rolband DH, James D, Norton HJ. Clinical ladder: Nurses' perceptions and satisfiers. J Nurs Adm. 2009. 39:182–188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e31819c9cc0.

26. Sohng KY, Noh CH. An analytical study of the professional self-concept of hospital nurses in Korea. J Nurs Acad Soc. 1996. 26:94–106.

27. Strasen L. Self concept: Improving the image of nursing. J Nurs Adm. 1989. 19(1):4–5.

28. Yang GM. Analysis of the relationship between the empowerment the job-related individual characteristics and the work performance of nurses. 1999. Seoul, Korea: Kyung Hee University;Unpublished doctoral dissertation.

29. Yom YH. The workplace empowerment on staff nurses' organizational commitment and intent to stay. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2006. 12:23–31.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download