Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

Commensality, eating together with others, is a major representation of human sociality. In recent time, environments around commensality have changed significantly due to rapid social changes, and the decline of commensality is perceived as a serious concern in many modern societies. This study employs a cross-cultural analysis of university students in two East Asian countries, and examines cross-cultural variations of perceptions and actual practices of commensality and solo-eating.

SUBJECTS/METHODS

The analysis was drawn from a free-list survey and a self-administrative questionnaires of university students in urban Korea and Japan. The free-listing survey was conducted with a small cohort to explore common images and meanings of commensality and solo-eating. The self-administrative questionnaire was developed based on the result of the free-list survey, and conducted with a larger cohort to examine reasons and problems of practices and associated behaviors and food intake.

RESULTS

We found that Korean subjects tended to show stronger associations between solo-eating and negative emotions while the Japanese subjects expressed mixed emotions towards the practice of solo-eating. In the questionnaire, more Korean students reported they prefer commensality and tend to eat more quantities when they eat commensally. In contrast, more Japanese reported that they do not have preference on commensality and there is no notable difference in food quantities when they eat commensally and alone. Compared to the general Korean cohort finding, more proportion of overweight and obese groups of Korean subjects reported that they tend to eat more when they are alone than normal and underweight groups. This difference was not found in the overweight Japanese subjects.

Eating is not only a physiological event but also a social occasion. Empirical studies showed that the presence and the absence of others while eating have significant impacts on experiences of eating. For example, pleasure and stress of eating are closely related to the presence and the absence of others during mealtime [1]. For some people, eating alone is not regarded as a meal but a snack [23]. Influences of social factors are greater than physiological factors like hungers and satiety, and even affect individual consumption of food [4].

At the same time, there is a popular concern that the practice of commensality has been waned along with rapid social changes toward individualization [5]. One of factors influencing eating patterns is the change of living arrangements [6]. In fact, an increasing number of people live alone in many developed societies [7]. Although some studies showed cross-cultural variations of everyday eating practices among western modern societies like Europe and the United States [89], there are few studies which examine the situations in non-western settings.

Korea and Japan are modern societies in East Asia which share similar social and economic conditions to western societies. However, the trajectories of modernization in East Asia are not identical to the one occurred in the West. Kyung-Sup Chang remarked the process of modernization in South Korea were "compressed" in a shorter period of time that western societies spent few centuries to proceed [10]. Emiko Ochiai also argued that Japan has experienced a divergent path to modernization from the West while the Japanese experiences were not "compressed" as South Korea [11].

The divergent trajectories were also identified in the change of diets and health profiles. After the World War II, both the Korean and the Japanese consume more animal products which resulted in a rapid increase of fat intake [12]. The dietary changes at the population level are considered as a major determinant of increasing mortality of non-communicable diseases and number of obese populations [13]. Indeed, the proportion of obesity and non-communicable diseases are increasing over time in two countries [1415].

Young adulthood is an important stage of life where many people develop everyday habits. Sharing meals with family and friends function as "rite of passage" to adulthood [16], as solo-eating generates a sense of independence [17]. Poor eating habits acquired in young ages increase risks for developing obesity, other non-communicable diseases and mental health problems in the long run [18]. There is a fact that body mass index (BMI) of younger generations increased faster than previous generations [19]. A similar trend was identified among Korean and Japanese men, but the trend among young women was rather reversed [2021]. Being a university student is a vital part of socialization to adulthood in contemporary Korea and Japan. A larger cohort of young adults aged between 25 and 34 in Korea and Japan received tertiary education than previous generations, and the generation difference was largest among developed countries [22]. A group of university students in two countries are not just a group of student cohort but also a group of young adults in similar ages.

Lack of consensus between lay population and public health professionals is common [2324]. Understanding of lay people's views dramatically improved the effectiveness of health advices and interventions [25]. Cultural Consensus Analysis (CCA) is a research method developed in cognitive anthropology and employed to explore cultural domains of topics shared among a group of people. A cultural domain means "an organized set of words, concepts or sentences" shared among a group of people [26]. CCA is particularly suitable to understand the perspective of subjects, so-called an emic perspective [27]. By applying CCA in combination with self-administrative questionnaire from a larger cohort of students, our study investigates different experiences between commensality and solo-eating among student subjects and cross-cultural variations of these experiences between Korean and Japanese groups.

The subject was a non-probability, convenience sample of university students living and studying in urban Korea and Japan. Students were recruited at university's classrooms in two countries. Recruitment and data collections were conducted from 2011 to 2013. All data collections in Korea were conducted in Korean by Korean authors and the ones in Japan were conducted in Japanese by Japanese authors. Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Investigation Review Board of Gachon University of Medicine (2011-04) and Kawagawa Institute of Technology (2011-007 for the free-listing survey in Japan and 2012-006 for the self-administrative survey in Japan). All subjects were assured that their information was confidential and their identities would never be revealed. Data were anonymized before analysis.

Cross-cultural analyses derive from two surveys: free-listing and self-administrative questionnaire. A free-listing survey was employed to understand common images and meanings of commensality and solo-eating among students. Free-listing is a major research technique of CCA. It not only provides more flexibility to respondents than close-ended questionnaires, but also prevents from enforcing researcher's preoccupations [28]. CCA shows decent validity with a small sample size of four subjects who share similar social backgrounds, though there tend to be a smaller error variance with a larger samples [29].

After a brief explanation about the study and informed consent, all students were asked to list any words and sentences they think related to each questions within 60 seconds. After the 60 seconds have passed, students were asked to stop writing and move on the next question. The free-listing survey consisted of nine questions: eating with others, eating alone, eating with family, eating with friends, traditional meals, contemporary meals, healthy body/weight, obesity, and underweight. Relying on free-listing data only is not recommended [30]. There are possibilities that some subjects may misunderstand the topics and use their random guess [29]. Combinations with other methods like follow-up interviews and questionnaires are crucial to understand contexts of topics [30].

Because of these backgrounds, a self-administrative questionnaire was developed based on the result of free-listing survey, and employed to examine actual practices of commensality and solo-eating among students. Similarly to the free-list survey, all students were asked to answer the questionnaire after a brief explanation and informed consent. The questionnaire composed a combination of multiple-choice and free-response questions of a range from images, frequency, timing, and reasons for commensality and solo-eating to eating behaviors and food choices when they eat with commensally and alone.

All responses obtained in Korean and Japanese for the free-listing survey were translated into English, in order to identify phases and words which represent similar meanings across two cultural groups (Koreans and Japanese). All translated data was coded by topics and semantic similarities of words. The semantic similarities were determined by English thesaurus. Coding was conducted based on the guideline for grounded theory [31]. Duplicated responses from a subject were excluded from the analysis. The total of 14 topics and 170 codes were generated from the responses to commensality and solo-eating from Korean and Japanese groups. Frequency of words and topics was examined to access consensus within and across cultural groups. In other words, most words and topics frequently listed among members of a cultural group are regarded as the ones which achieved a high level of consensus among the group.

All data from the self-administrative survey were analyzed using SPSS version 19.0. Missing data was excluded from data analyses. The distribution of data are examined and presented by numbers of responses and their proportion. Two-sample t-test was used to assess differences of means. Chi-square test was employed to assess differences between two cultural groups and demographic backgrounds. For the comparison by body shape, all subjects were divided into four categories by BMI calculated by their self-reported height and weight. Following the Asian BMI cut-off by International Obesity Taskforce [32], a BMI of less than 18.5 was considered as underweight, the one between 18.5 and 23 as normal, the one between 23 and 25 as overweight, and the one higher than 25 as obese.

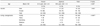

The total of 185 university students lived and studied in urban Korea and Japan aged 18-27 years old participated in the free-listing surveys in two countries. In both countries, a large proportion of subjects were women (86% in Korea and 73% in Japan). The average age of Korean subjects (23.2 years old) was older then the Japanese (19.0 years old). A large proportion of Japanese subjects (42%) lived alone than Koreans (8%). Demographics of university students who participated in the free-listing survey is shown in Table 1.

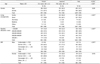

The total of 1,649 university students aged 18-29 years old administrative survey) participated in the self-administrative survey. Gender imbalance was improved compared to the free-listing survey, but the proportion of women (57.4% in Korea and 59.7% in Japan) was larger than men (42.6% in Korea and 40.3% in Japan). Similarly to the free-listing subject, the average age of Korean subjects (21.6 years old) was older than the Japanese (19.6 years old). More proportion of Japanese subjects (49.1%) lived alone than Koreans (19.8%). The mode of monetary allowance excluding housing costs was from 300,000 to 400,000 won per month among Korean subjects and from 200,000 to 300,000 won among Japanese subjects. Overall, Korean subjects reported higher allowance than Japanese (P < 0.05). The proportion of overweight and obese subjects were especially high among Korean male subjects (32.6% combined overweight and obese subjects) compared with Korean female and Japanese male and female subjects. More than 20% of Korean and Japanese female subjects were underweight (23.1% among Koreans and 20.5% among Japanese). Demographics of university students who participated in the self-administrative survey is shown in Table 2.

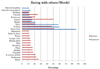

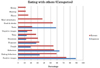

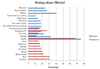

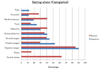

In the free-listing survey, more than 70% of Korean and Japanese students associated commensality (eating with others) with positive emotions like enjoyment and happiness and solo-eating (eating alone) with negative emotions like loneliness and boredom. Figs. 1 and 2 present words and topics which were listed among more than 10% of Korean and Japanese subjects associated with eating with others. Figs. 3 and 4 present words and topics which were listed among more than 10% of Korean and Japanese subjects associated with eating alone.

A similar response was obtained from the self-administrative survey. We asked subjects multiple-choice questions about their impressions of a person eating alone: "what sorts of impressions you get when you see a person eating alone?" There was a significant difference between the responses of Korean and Japanese subjects (P < 0.05), and the result is shown in Table 3. We found that 55.5% of Korean subjects chose "Lonely" while only 21.4% of Japanese chose this answer. In contrast, 34.9% of Japanese subject chose "Liberty" while only 13.5% of Koreans chose it.

A range of multiple-choice questions related to the comparison between practices of commensality and solo-eating are shown in Table 4. Significant differences between responses of Korean and Japanese subjects were identified in the questions about food intake, menu, preference, and frequency (P < 0.05). In the questionnaire, all subjects were asked to compare their experiences between when they eat alone and with others. More than 75% of Korean subjects reported that they prefer eating with others to eating alone compared to about 60% of Japanese. Instead, 33% of Japanese reported they do not have preferences between two practices.

In terms of actual practices of commensality and solo-eating, about one third of Japanese subjects reported that they ate alone more than eating with others in last seven days, while only 13.2% of Korean reported they ate alone more. Regarding contents of meals, about 47% of Korean reported they tend to eat more amount of food when they are with others compared to about 31% of Japanese. About 48% of Japanese reported that there is no difference of food quantities when they are with others and alone. More than 81% of Korean reported that they tend to eat more variety of foods and dishes when they are with others, compared to about 69% of Japanese. More proportion of Japanese reported that they tend to eat less variety (10.6%) and there was no difference in menu (20.6%) than Koreans. The result of cross-cultural comparison indicates that the experiences of eating among Korean subjects are more likely to be affected by commensality and solo-eating than that of Japanese.

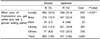

Within-group comparison was conducted by BMI of subjects, and the result is shown in Table 5. There was no significant difference in the questions about preference and menu between commensality and solo-eating across the BMI groups. Differences between BMI groups were identified in the question about differences of food intake among Korean and Japanese subjects (P < 0.05). The distribution of responses across BMI groups were varied between two cultural groups. About 50% of Korean underweight and normal groups reported that they tend to eat more when they are with others. In contrast, a similar proportion of Japanese underweight and normal groups reported there is no difference in food intake between when they are with others and alone. In addition, more proportion of overweight and obese groups among Korean subjects reported that they tend to eat more when they are alone than their normal and underweight groups. However, the difference was not found in the overweight Japanese subjects.

We investigate cross-cultural similarities and variations of images and meanings and actual practices of commensality and solo-eating among university students in urban Korea and Japan. We found explicit differences between Korean and Japanese subjects in both free-listing and self-administrative surveys. More Korean subjects reported different emotions and eating behaviors when they eat with others and alone. In contrast, more Japanese subjects reported mixed emotions associated with solo-eating, and that there was no notable difference in eating behaviors when they eat with others and alone.

Our study contributes to the current literature on commensality and solo-eating by providing cross-cultural transferability of its theories in a non-western setting. A cross-cultural comparison of Korean and Japanese general cohorts supported that cultural attachment to commensality and social acceptance of solo-eating vary across modern societies, as suggested by Fischler [9]. Unlike previous literature, however, a cross-cultural comparison by BMI groups suggested that the relationship with obesity can also be subject to cultural constraints. Different eating behaviors of obese individuals in social and solitary settings were widely studied from the late 1960s in western societies, and suggested that obese individuals tended to become more self-conscious about their impressions to others compared to normal-weight individuals [3334353637]. Nevertheless, the current study, especially the result of Japanese subjects, did not support the previous literature, while Korean subjects showed a moderate tendency. This may be related to cross-cultural variations in social representations of obesity [3839].

We note some limitations of the current study. Our analyses reply on self-report data of individual's perceptions and actual practices of commensality and solo-eating. In particular, frequency of these practices and food intake associated with them are subject to respondents' interpretations of questions as well as their memories about past experiences [40]. In addition, there was a significant difference in the number of subjects who lived alone between Korean and Japanese groups, and it may influence a moderate acceptance of eating alone among Japanese subjects. The current study employed convenience sampling. Quota or probability sampling would improve imbalance of subjects who live alone and live with someone.

In conclusion, commensality and solo-eating account for significant parts of everyday eating in modern societies. These practices play important roles in determining a wide range of eating experiences including feelings and food intake associated with them, which may influence both physical and mental health in the long run. Moreover, either eating commensally or alone could also influence subject's responses to any questions related to diets, because eating is inseparable from everyday human sociality.

Figures and Tables

Notes

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF)'s the 2011 Korea-Japan Basic Scientific Cooperation Program and Japan Society's Promoting Science (JSPS)'s Bilateral program. We thank Dr. Megumi Tsubota-Utsugi for her contribution to data collection and analyses of questionnaire.

References

1. Danesi G. Pleasure and stress of eating alone and eating together among French and German young adults. J Eat Hosp Res. 2012; 1:77–91.

2. Workshop summary: What to eat: a multidiscipline view of meals. Food Qual Prefer. 2004; 15:901–905.

3. Pliner P, Bell R. A table for one: the pain and pleasure of eating alone. In : Meiselman HL, editor. Meals in Science and Practice: Interdisciplinary Research and Business Applications. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing;2009. p. 169–185.

4. Herman CP, Roth DA, Polivy J. Effects of the presence of others on food intake: a normative interpretation. Psychol Bull. 2003; 129:873–886.

5. Mennell S, Murcott A, van Otterloo AH. The Sociology of Food: Eating, Diet and Culture. Newbury Park (CA): Sage;1992.

6. Mestdag I, Glorieux I. Change and stability in commensality patterns: a comparative analysis of Belgian time-use data from 1966, 1999 and 2004. Sociol Rev. 2009; 57:703–726.

7. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (FR). Figure 2.3. Home alone: the rise in single-person households. Trends in Shaping Education 2013. Paris: OECD publishing;2013. p. 40.

8. Warde A, Cheng SL, Olsen W, Southerton D. Changes in the practice of eating: a comparative analysis of time-use. Acta Sociol. 2007; 50:363–385.

10. Chang KS. Compressed modernity and its discontents: South Korean society in transtion. Econ Soc. 1999; 28:30–55.

11. Ochiai E. Leaving the West, rejoining the East? Gender and family in Japan's semi-compressed modernity. Int Sociol. 2014; 29:209–228.

13. World Health Organization (CH). Globalization, Diets and Noncommunicable Diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization;2002.

14. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea Health Statistics 2011: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES V). Cheongwon: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2012.

15. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (JP). The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan 2013. Chiyoda: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare;2015.

16. Danesi G. Commensality in French and German young adults: an ethnographic study. Hosp Soc. 2012; 1:153–172.

18. Furlong A. Youth Studies: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge;2013.

19. Allman-Farinelli MA, Chey T, Bauman AE, Gill T, James WP. Age, period and birth cohort effects on prevalence of overweight and obesity in Australian adults from 1990 to 2000. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008; 62:898–907.

20. Funatogawa I, Funatogawa T, Nakao M, Karita K, Yano E. Changes in body mass index by birth cohort in Japanese adults: results from the National Nutrition Survey of Japan 1956-2005. Int J Epidemiol. 2009; 38:83–92.

21. Khang YH, Yun SC. Trends in general and abdominal obesity among Korean adults: findings from 1998, 2001, 2005, and 2007 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J Korean Med Sci. 2010; 25:1582–1588.

22. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (FR). Education at a Glance 2014: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD publishing;2014.

23. Smith CS, Morris M, Hill W, Francovich C, McMullin J, Chavez L, Rhoads C. Cultural consensus analysis as a tool for clinic improvements. J Gen Intern Med. 2004; 19:514–518.

24. Jauho M, Niva M. Lay understandings of functional foods as hybrids of food and medicine. Food Cult Soc. 2013; 16:43–63.

25. Farmer P. Infections and Inequalities: The Modern Plagues. Berkeley (CA): University of California Press;1999.

26. Weller SC, Romney AK. Systematic Data Collection. Newbury Park (CA): Sage publication;1988.

27. Schrauf RW, Sanchez J. Using freelisting to identify, assess, and characterize age differences in shared cultural domains. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008; 63:S385–S393.

29. Romney AK, Weller SC, Batchelder WH. Culture as consensus: a theory of culture and informant accuracy. Am Anthropol. 1986; 88:313–338.

30. Quinlan M. Considerations for collecting freelists in the field: examples from ethobotany. Field Methods. 2005; 17:219–234.

31. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage publications;2006.

32. Kanazawa M, Yoshiike N, Osaka T, Numba Y, Zimmet P, Inoue S. Criteria and classification of obesity in Japan and Asia-Oceania. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2002; 11:S732–S737.

33. Schachter S, Goldman R, Gordon A. Effects of fear, food deprivation, and obesity on eating. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1968; 10:91–97.

34. Maykovich MK. Social constraints in eating patterns among the obese and overweight. Soc Probl. 1978; 25:453–460.

35. Conger JC, Conger AJ, Costanzo PR, Wright KL, Matter JA. The effect of social cues on the eating behavior of obese and normal subjects. J Pers. 1980; 48:258–271.

36. Heatherton TF, Baumeister RF. Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychol Bull. 1991; 110:86–108.

37. Salvy SJ, Coelho JS, Kieffer E, Epstein LH. Effects of social contexts on overweight and normal-weight children's food intake. Physiol Behav. 2007; 92:840–846.

38. Ulijaszek SJ. Frameworks of population obesity and the use of cultural consensus modeling in the study of environments contributing to obesity. Econ Hum Biol. 2007; 5:443–457.

39. Lee Y, Sun L. The study of perception in body somatotype and dietary behaviors: the comparative study between Korean and Chinese college students. Korean J Community Nutr. 2013; 18:25–44.

40. Tourangeau R. Remembering what happened: memory errors and survey reports. In : Stone AA, Bachrach CA, Jobe JB, Kurtzman HS, Cain VS, editors. The Science of Self-Report: Implications for Research and Practice. Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum;2000. p. 29–48.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download