Abstract

Fast food is popular among children and adolescents; however, its consumption has often been associated with negative impacts on nutrition and health. This study examined current fast food consumption status among middle school students and explored factors influencing fast food consumption by applying Theory of Planned Behavior. A total of 354 (52.5% boys) students were recruited from a middle school. The subjects completed a pre-tested questionnaire. The average monthly frequency of fast food consumption was 4.05 (4.25 for boys, 3.83 for girls). As expected, fast food consumption was considered to be a special event rather than part of an everyday diet, closely associated with meeting friends or celebrating, most likely with friends, special days. The Theory of Planned Behavior effectively explained fast food consumption behaviors with relatively high R2 around 0.6. Multiple regression analyses showed that fast food consumption behavior was significantly related to behavioral intention (b = 0.61, P < 0.001) and perceived behavioral control (b = 0.19, P < 0.001). Further analysis showed that behavioral intention was significantly related to subjective norm (b = 0.15, P < 0.01) and perceived behavioral control (b = 0.56, P < 0.001). Attitude toward fast food consumption was not significantly associated with behavioral intention. Therefore, effective nutrition education programs on fast food consumption should include components to change the subjective norms of fast food consumption, especially among peers, and perceived behavioral control. Further studies should examine effective ways of changing subjective norms and possible alternatives to fast food consumption for students to alter perceived behavioral control.

Food service industry in Korea blossomed in the 1990s largely due to the needs created by the 1986 Asian Games and the 1988 Olympic Games [1]. In addition, westernization pursuing diversity, speed, and convenience was widely spread in daily life, which further promoted the development of the fast food industry. Labensky et al. [2] define fast food as "Food dispensed quickly at an inexpensive restaurant generally offering a limited menu of inexpensive items, many of which may not be particularly nutritious; the food can be eaten on premises, taken out or sometimes delivered." Typical fast foods include hamburgers, French fries, pizza, fried chicken, and doughnuts. The Korean fast food industry posted a rapid and significant average annual growth of 39.7%, illustrated by a sales increase from 55.2 million Korean won in the 1990s to current 1.38 billion Korean won [3]. The impressive growth rate of the fast food industry seemed to plateau shortly after the year 2000, but the total sales remain high. The total sales of fast food restaurants specializing in pizza, hamburgers, and fried chicken in 2006 were 3.3 billion Korean won, 6.48% of total sales from all restaurants [3,4].

The most frequent consumers of fast foods are people in their teens and twenties, probably because these foods are fast, convenient, and relatively inexpensive [5-7]. According to a study conducted by Lee in Pusan [7], fast foods were consumed once or twice monthly by 38.5% of elementary school students and 40.5% of high school students, rates higher than those observed in people in their forties or fifties. A similar trend was seen for those individuals consuming fast foods more than once per week. Both elementary and high school students indicated taste and low cost as reasons for patronizing fast food stores. Another study in a small city also found more frequent fast food consumption by people in their teens and twenties. When asked for reasons why they frequented fast food stores, teen's listed fast service, convenience, taste, and price, in that order [6].

Frequent consumption of fast foods by adolescents may be detrimental to their growth and development [8]. The adolescent period is when physical and mental growth and development are rapid, resulting in high energy and nutritional needs. Therefore, people in this age group should try to adhere to adequate and appropriate diets [9]. The Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBWS) [10] found poor dietary behaviors and nutritional imbalance to be two of the main health behavior problems in Korean youth. Some adolescents consumed fast and processed foods, while many adolescents did not consume recommended foods such as fruits, vegetables, milk, etc. The survey found that 32.3% of adolescents consumed one or more servings of fruit per day, 16.5% consumed three or more servings of vegetables per day, 15.2% consumed more than 2 cups of milk per day, 68.4% ate fast food more than once per week, and 72.5% ate instant noodles more than once per week. There is concern over these high rates of fast food consumption because of the high energy, fat, and sodium content found in them. Research has shown that frequently eating fast food leads to high consumption rates of energy, total fat, saturated fat, and sodium and low consumption rates of vitamin A, vitamin C, milk, fruits, and vegetables [11-13]. High rates of fast food consumption can lead to chronic disease, including obesity, diabetes, and hypertension [14,15]. For example, fast food consumption was positively related to weight gain and insulin resistance, leading to an increased risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes [16,17].

Regularly consuming fast food negatively influences overall dietary behaviors. Frequent fast food consumption was associated with lower scores of dietary behaviors, dietary attitude, and nutrition knowledge as well as irregular and picky eating among children and adolescents [13,18,19]. Previous studies [5,20] reported that adolescents themselves also felt that frequent fast food consumption caused "westernization of taste," "favoring eating-out," and "liking salty food."

There is increasing needs for nutrition education on the appropriate use of fast food. Designing useful nutrition education requires a good understanding of factors affecting fast food use. Most research related to fast food has focused on it as a part of snack consumption [21-24] or has consisted of simple analyses of consumption rates and patterns [6,7,25-28].

There have been several studies focused on fast food use, related dietary behaviors, and nutrition knowledge level [5,13,18-20,29-31] and only one study [32] systematically examined the factors influencing fast food use among college students. Therefore, this study attempted the systemic examination among adolescents to promote the healthier use of fast foods.

This study applied the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to understand factors influencing fast food use. The TPB is an extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) by Ajzen [33]. The TRA explains human behaviors as they relate to attitude and subjective norm, while the TPB also includes perceived behavioral control. That is, the TPB proposes that human behaviors are determined by behavioral intention affected by attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. In relation to fast food use, "attitude" would be personal positive or negative feelings toward fast food use, while "subjective norm" would be how much a person desires to respect and follow the opinions of individuals who are important to him or her. "Perceived behavioral control" would be a person's perceived capabilities and his or her belief in use or disuse of fast food in their environments. The TPB has been used to examine various topics in public health, such as healthy food choice [34-37], dairy consumption [38], and fast food consumption [32].

The goals of this study were to examine current fast food consumption rates among middle school students and to explore the factors influencing fast food use with the TPB. The information and knowledge gained in this study will be useful in designing nutrition education programs promoting better eating habits.

Subjects of this study were recruited from four middle schools (one boy's, one girl's, and two co-ed) in Seoul. Students were asked to complete a pre-tested questionnaire under the supervision of a teacher. All of the 405 distributed questionnaires were returned; however, 51 partially completed questionnaires were excluded. This left a total of 354 questionnaires, a response rate of 87.4%.

The questionnaire used in this study was developed through a two-step process. First, we asked 20 middle school students to freely write the pros and cons of fast food use and those factors enabling and disabling its consumption. Based on the information acquired and previous studies [33-37,39,40], a questionnaire was developed for this study. The questionnaire was then pre-tested with 40 middle school students. Based on the results from the pre-test, some changes in wording were made for the final version of the questionnaire.

The study gathered information about the students' general characteristics, fast food consumption, attitude toward fast food use, subjective norm toward fast food use, perceived behavioral control of fast food use, and intention of fast food use.

General characteristics included sex, height, weight, parents' education, parents' working status, interest in health, interest in body weight management, and whether the students ate alone. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from reported weight and height. BMI was used to determine each student's weight status according to the 2007 Korean Growth Standard. Underweight was defined as having a BMI lower than the 5th percentile, overweight was defined as having a BMI between the 85th and 95th percentile, and obesity was defined as having a BMI in the 95th percentile or higher. If a student had a BMI greater than 25, he or she was considered obese regardless of his or her BMI percentile [41].

Fast food use was examined by frequency of consumption, days when it was used often, people with whom the students used fast foods, the purpose of its use, and the places where it was often used. "Fast food" was defined as pizza, fried chicken, hamburgers, French fries, or doughnuts. The frequency of fast food use was analyzed for each food category.

Behavioral intention to use fast food was determined with the question, "How often do you think you will consume a hamburger in the next month?" The same question was asked about French fries, pizza, fried chicken, and doughnuts for a total of five questions in this category. A 4-point Likert scale (1: not at all, 2: a little, 3: somewhat, 4: very much) was used to respond to these questions.

Attitude toward fast food use was explored with questions about the pros and cons of fast food consumption. A total of 12 questions were developed with possible answers given on a 4-point Likert scale (1: not at all, 2: a little, 3: somewhat, 4: very much). Questions pertained to the topics of familiarity, health, nutrition, taste, store atmosphere, sanitation, fullness after eating, energy content of fast food, salt content of fast food, fat content of fast food, and beliefs about the relationship between fast food and body weight. Cronbach's alpha among the 12 questions was 0.886, showing a reasonable level of internal reliability.

Subjective norm is determined with normative belief and motivation to comply [33]. Normative belief was examined by asking the students three questions about how they perceived the opinions of people important to them (parents, teachers, and friends) regarding fast food use. Motivation to comply was examined by asking the students how much they respected and followed the opinions of people important to them. The responses to all questions were given on a 4-point Likert scale (1: not at all, 2: a little, 3: somewhat, 4: very much). Cronbach's alpha for normative belief and for motivation to comply was 0.592 and 0.738, respectively. The Internal reliability for normative belief was relatively low because the opinions of students' friends tended to be different from those of their parents and teachers.

Perceived behavioral control was explored with thirteen questions concerning the enabling and disabling factors for fast food use, which were also answered with a 4-point Likert scale (1: not at all, 2: a little, 3: somewhat, 4: very much). The internal reliability of these questions was good, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.886.

All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 12.0. Simple statistics, such as frequencies, means, and standard deviations were used along with t-tests and χ2-tests. A Pearson correlation test was conducted to examine the relationships between factors of the TPB and fast food use, and multiple regressions were used to further the analysis.

The general characteristics of the subjects are presented in Table 1. A total of 354 middle school students (52.5% boys) participated in this study. The average height and weight for boys were 167.0 cm and 57.3 kg, respectively and 160.4 cm and 50.6 kg, respectively, for girls. The majority of the subjects had a normal body weight, while 1.4% were overweight and 5.6% were obese. A total of 44% of the subjects reported a high level of interest in health. The subjects were also interested in weight control, with girls showing a higher interest level than boys. Approximately 8% of the subjects ate meals alone.

Fast food consumption patterns of the subjects are shown in Table 2. Subjects consumed fast foods (any type) an average of 4.05 times per month. Hamburgers and fried chicken were consumed more frequently than French fries, pizza, or doughnuts. Hamburgers were more frequently consumed by boys (1.27 times per month) than girls (0.81 times per month), and the opposite was true for doughnuts (both differences significant).

Fast foods were consumed on special days (33.9%) or when meeting friends (25.7%). This was supported by the subjects choosing fast food outlets downtown (59.9%) as opposed to those near home or school. That the subjects ate fast foods while they were with friends (61.6%) also supported that fast food consumption was associated with special days or friends. Boys answered that they also chose to eat fast food when they were hungry (23.1%). More girls (63.7%) ate fast food as a meal, while more boys (54.8%) ate fast food as snack.

The behavioral intention to consume fast food averaged 10.92 out of a possible maximum score of 20, the sum of the five scores on the intention to consume hamburgers, French fries, pizza, fried chicken, or doughnuts. Therefore, the averaged score of 10.92 appeared to be somewhere between 'a little' and 'somewhat'. No gender differences were found in the summed score; however, boys appeared to have a higher intention to consume hamburgers than girls (Table 3).

Table 4 shows students' attitudes toward fast food consumption. The average score of overall attitude was 24.55 out of 48. The subjects showed strong positive attitudes toward taste, fast food store environments, and familiarity and strong negative attitudes toward saltiness of fast food. Boys had a significantly stronger attitude toward taste and saltiness of fast food than did girls (P < 0.01).

Subjective norm was examined for family, teachers and friends (Table 5). Motivation to comply and normative belief were questioned separately, and the subjective norm was obtained by multiplying the motivation to comply score by the normative belief score. While motivation to comply showed very similar scores for family, teachers and friends, normative belief was stronger with friends. Therefore, the subjective norm about fast food consumption for friends was higher than for family or teachers. In addition, boys tended to think that family would like their fast food consumption more than girls (P < 0.01). Because of this difference, boys had a higher total subjective norm score than girls (P < 0.05).

27.5 out of 52 (Table 6). Boys showed higher scores than girls, although this difference was not significant. Questions resulting in higher scores were those concerning fewer fast food stores, fewer advertisements, and fewer sales promotions. The question resulting in the lowest score concerned finding other places to meet friends. Three questions showed differences in gender. Girls reported more difficulty than boys in eating fast food while on a diet (P < 0.001) and in changing their current fast food consumption behaviors (P < 0.01).

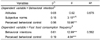

The variables of the Theory of Planned Behaviors were significantly and positively correlated (P < 0.01, Table 7). In particular, fast food consumption behavior was highly (r = 0.736) correlated with behavioral intention.

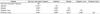

Multiple regression analyses were conducted to determine the relative importance of the variables of the Theory of Planned Behaviors to fast food consumption behaviors (Table 8). When attitude toward behavior, subjective norms, and perceived control were regressed against behavioral intention, the model was highly significant (P = 0.000) and explained a good proportion of the variance (R2 = 0.675). Behavioral intention, the dependent variable in this model, indicated the a total score of intention to consume fast food shown in Table 3. While attitude was not significant, subjective norms and perceived controls were significantly associated with the intention to consume fast food. Perceived behavioral control seemed to be the most important of the three variables.

The second model, using fast food consumption as a dependent variable, was also highly significant (P = 0.000) and explained more than half of the variance. In this model, the dependent variable, fast food consumption, meant the total monthly consumption frequency of all kinds of fast food shown in Table 2. Both behavioral intention and perceived behavioral control were significantly associated with fast food consumption, of which behavioral intention appeared to be more important. No significant gender differences were found in these relationships.

This study investigated fast food consumption status among middle school students. It also examined the factors affecting fast food consumption by applying the Theory of Planned Behaviors.

The average weight and height for boys in this study were 57.3 kg and 167.0 cm, repeatedly, and 50.6 kg and 160.4 cm, respectively, for girls. These results for height were slightly taller than those from the 2007 Korean children and adolescents' growth standards [41]. A majority (90%) of the participants were determined to have normal body weight by BMI, while 1.4% and 5.6% were overweight and obese, respectively. This body weight status distribution differs from that found in the 2007 Korean Nutrition and Health Examination Survey (KNHANES) [42]. The 2007 KNHANES showed distributions of 79.4% normal weight, 5.1% overweight, and 15.5% obesity 15.5%. This discrepancy is likely due to methodological differences in the two datasets. The 2007 KNHANES used direct measurements of weight and height, but this study relied on self-reported information.

This study found the average monthly frequency of fast food consumption to be 4.05 (4.25 among boys, 3.83 among girls). According to the third Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBWS) [10], 62.5% of middle school students consumed fast food more than once per week. Cho and Han [5] found that most (42% of boys and 49.4% of girls) middle school students tended to consume fast food "once or twice per week." Other studies on fast food consumption reported similar results [7,18,31,43]. Hamburgers were the fast food most often consumed at 1.05 times per month, closely followed by fried chicken at 1.02 times per month, and pizza at 0.97 times per month. This trend is supported by other studies. A study on fast food consumption among college students in Daejeon [32] reported the monthly frequencies of types of fast food consumption to be 2.7 for hamburgers, 2.1 for French fries, 1.8 for chicken, 1.5 for pizza, and 0.8 for doughnuts.

In this study, more boys (54.8%) ate fast food as snack and more girls (63.7%) ate fast food as a meal. Other studies have reported mixed results on this topic. Jeong and Kim [43] found that both male and female high school students ate fast food as a meal. However, other studies [26,28,31] found that more students ate fast food as a snack. Nutrition education about the energy content of fast food could help to prevent its overconsumption from eating fast foods as snacks.

This study found that fast food consumption by middle school students was closely associated with friends. Most subjects in this study answered that they ate fast food downtown (59.9%) rather than near their home or school. Jeong and Kim [43] found similar results among high school students. This may be related to the fact that participants in this study answered that they used fast food for special days (33.9%) or meeting friends (25.7%). In addition, 61.6% of the subjects said that they ate fast food with friends. Other studies [19,27,29,43] also found that fast food consumption was related to meeting or celebrating with friends. That is, middle school students in this study typically did not eat fast food in the context of everyday life. Therefore, effective nutrition education should provide other choices for meeting friends or celebrations.

The theory of Planned Behavior explained fast food consumption behaviors with a reasonable level of R2 (0.562 and 0.675 for each model). This study found a moderate attitude toward fast food consumption with a score of 24.55 out of 48. Items showing comparably strong levels of attitude were taste, store environment, familiarity, and saltiness. These items were also found to be important in other studies of fast food consumption. Yoon and Wi [27] found that clean, hygienic environments and good taste were important reasons for choosing fast food. Lee [7] found that elementary and high school students in Busan chose fast food because they liked the taste. Another study [18] in Busan also found that taste was chosen as the most important reason for consuming fast food.

As expected, friends appeared to be the most influential people for the participants' fast food consumption. Although the subjects' motivation to comply was similar for family, teachers, and friends, their normative belief was higher and more positive with friends than with family and teachers. This finding shows that nutrition education about fast food consumption for students should emphasize changing the norm among students.

The level of perceived behavioral control was also found to be moderate, with a score of 27.5 out of 52. In general, boys showed a higher level of perceived behavioral control (28.09) than girls (26.85), which means boys may continue fast food consumption regardless of external factors.

A Pearson correlation test was conducted to examine correlation among the constructs of the Theory of Planned Behaviors. This study found that higher intention, perceived behavioral control, attitude, and subjective norm led to higher rates of fast food consumption, as the theory describes. Positive correlations between these constructs were also found other studies [37,38,44,45], but the correlation coefficients in this study tended to be higher than those reported in other research.

Multiple regression analyses showed that behavioral intention was affected by subjective norms (b = 0.15) and perceived behavioral control (b = 0.56). Interestingly, attitude toward fast food did not significantly affect behavioral intention. Behavioral intention (b = 0.61) was highly associated with fast food consumption and perceived behavioral control (b = 0.19).

This study was limited by its cross-sectional nature. Participants' intention to use fast food was determined by asking whether they planned to use it within a month. A prospective study with a start and end point would garner more accurate information. Further research on fast food consumption should consider this time issue as well as possible ways to change subjective norms and provide alternatives to fast food restaurants for meeting friends.

Effective nutrition education programs result in behavioral changes. Such programs include components for addressing factors affecting the behaviors of the nutrition education targets. Therefore, research on the factors contributing to dietary behaviors should advance nutrition education. The purpose of this study was to identify the important factors affecting fast food consumption. Results indicated that providing alternatives to fast food stores and changing subjective norms regarding fast food may be key focus points in changing fast food consumption patterns among middle school students. Future nutrition education programs would benefit from including these issues regarding fast food consumption.

Figures and Tables

Table 8

Multiple regressions on consumption of fast food

1) Standardized parameter estimate

2) Behavioral Intention in this model was intention to use fast food in a month, shown in table 3.

Model df = 353 model F = 97.64, P = 0.000

3) Fast food consumption frequency in this model was total frequency of fast food consumption in a month, as shown in table 2. Model df = 353 model F = 224.88, P = 0.000

4) **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

References

1. Lee EJ, Choi HS. A study on the change of food service industry and pattern of dietary externalization in Korea. Korean J Hosp Adm. 2005. 14:355–367.

2. Labensky S, Ingram GG, Labensky SR. Webster's New World Dictionary of Culinary Arts. 1997. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall;146.

3. Han KS, Seo KM, Park HN, Hong SY. Issues of Korean restaurant industry by content analysis of food yearly statistics. Korean J Food Cult. 2004. 19:313–325.

4. Korea Statistic [Internet]. c2006. cited 2010 September 30. Seoul: Korean Statistical Information Service;Available from: http://kosis.kr/abroad/abroad_01List.jsp.

5. Cho CM, Han YB. Dietary behavior and fast-foods use of middle school students in Seoul. J Korean Home Econ Educ Assoc. 1996. 8:105–119.

6. Park MR, Kim SH, Wi SU. The consumption patterns of fast food in small cities. Korean J Food Cult. 1999. 14:139–146.

7. Lee JS. A comparative study on fast food consumption patterns classified by age in Busan. Korean J Community Nutr. 2007. 12:534–544.

8. Sim KH. Nutritional status and opinions about fast food among Korean youth. 1992. Daejon: Chungnam National University;[master's thesis].

9. Ahn MS, Chung HK, Kim AJ, Shin SM, Han KS, Woo NRY, Kim HJ. Meal Management. 2008. Seoul: Soohaksa Co.;230–250.

10. Ministry of Health, Welfare and Family Affaires. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. The Third Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey. 2008. Seoul: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;126–147.

11. Paeratakul S, Ferdinand DP, Champagne CM, Ryan DH, Bray GA. Fast-food consumption among US adults and children: Dietary and nutrient intake profile. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003. 103:1332–1338.

12. Kim K, Park E. Nutrient density of fast-food consumed by the middle school students in Cheongju city. Korean J Community Nutr. 2005. 10:271–280.

13. Park EJ, Kim KN, Cho JS. Dietary habits and nutrient intake according to the frequency of fast food consumption among middle school students in Cheongju area. Hum Ecol Res. 2005. 9:165–178.

14. Choi NJ. A Report on Nutrient Content and Consumption Patterns of Fast Food. 2003. Seoul: Korea Consumer Agency;13–27.

15. Kim NS, Kim SA. Comparative assessment of lipid composition by food table and chemical analysis in fast-foods. Chungnam J Hum Ecol. 1995. 8:28–39.

16. Pereira MA, Kartashov AI, Ebbeling CB, Van Horn L, Slattery ML, Jacobs DR Jr, Ludwig DS. Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet. 2005. 365:36–42.

17. Isganaitis E, Lustig RH. Fast food, central nervous system insulin resistance, and obesity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005. 25:2451–2462.

18. Choi MK. A study on the relationship between fast food consumption patterns and nutrition knowledge, dietary attitude of middle and high school students in Busan. Korean J Culinary Res. 2007. 13:188–200.

19. Shin EK, Kim SY, Lee S, Bae I, Lee H. Fast food consumption patterns and eating habits of 6th grade elementary school children in Seoul. J East Asian Soc Diet Life. 2008. 18:662–674.

20. Sim KH, Kim SA. Utilization state of fast-foods among Korean youth in big cities. Korean J Nutr. 1993. 26:804–811.

21. Park YS. Intake of snack by the elementary school children in Hansan-do area 1. Korean J Food Cookery Sci. 2003. 19:96–106.

22. Kang SA, Lee JW, Kim KE, Koo JO, Park DY. A study of the frequency of food purchase for snacking and its related ecological factors on elementary school children. Korean J Community Nutr. 2004. 9:453–463.

23. Jo JI, Kim HK. Food habits and eating snack behaviors of middle school students in Ulsan area. Korean J Nutr. 2008. 41:797–808.

24. Youn HS, Kwak HJ, Noh SK. A study on dietary behaviors, snack habits and dental caries of high school students in Gimhae, Kyungnam province. Korean J Nutr. 2008. 41:809–817.

25. Mo SM, Kim CI, Lee SY, Yoon EY, Lee KS, Choi KS. A study on dining out behaviors of fast foods - focused on Youido apartment compound in Seoul. J Korean Soc Diet Cult. 1986. 1:295–309.

26. Kim CY, Nam SR, Kwak TK. Evaluation of nutrient density for fast foods selected by middle and high school students in Seoul. J Korean Soc Diet Cult. 1990. 5:361–369.

27. Yoon HJ, Wi SU. A survey of college student behaviors on fast food restaurants. Korean J Food Nutr. 1994. 7:323–331.

28. Lyu ES, Lee KA, Yoon JY. The fast foods consumption pattern of secondary school students in Busan area. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 2006. 35:448–455.

29. You DR, Park GS, Kim SY, Kim HH, Lee SJ. Fast food consumption patterns-focused on college students in Taegu·Kyungbuk. J Korean Home Econ Assoc. 2000. 38:27–40.

30. Kim KW, Shin EM, Moon EH. A study on fast food consumption nutritional knowledge, food behavior and dietary intake of university students. J Korean Diet Assoc. 2004. 10:13–24.

31. Lee SS. A study on dietary behavior of children according to their preferences for fast food. Korean J Community Nutr. 2004. 9:204–213.

32. Kim KW, Ahn Y, Kim HM. Fast food consumption and related factors among university students in Daejeon. Korean J Community Nutr. 2004. 9:47–57.

34. Øygard L, Rise J. Predicting the intention to eat healthier food among young adults. Health Educ Res. 1996. 11:453–461.

36. Verplanken B, Herabadi AG, Perry JA, Silvera DH. Consumer style and health: the role of impulsive buying in unhealthy eating. Psychol Health. 2005. 20:429–441.

37. Hewitt AM, Stephens C. Healthy eating among 10-13-year-old New Zealand children: understanding choice using the theory of planned behaviour and the role of parental influence. Psychol Health Med. 2007. 12:526–535.

38. Kim KW, Shin EM. Using the theory of planned behavior to explain dairy food consumption among university female students. Korean J Community Nutr. 2003. 8:53–61.

39. Bae EY. The influence of fastfood on food culture and development of computer-assisted nutrition education program for teenager. 2006. Changwon: Changwon National University;[master's thesis].

40. Chong YK, Sung YK, Ryu IY. The effects of fast food customers' perceived risk on purchasing intention, attitude, & risk reduction behavior. Korean J Food Cult. 2009. 24:518–524.

41. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Korean Pediatric Society. Korean National Growth Charts. 2007. Seoul: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;124.

42. Ministry of Health and Welfare and Family Affairs. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007 National Health Statistics-The 4th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2008. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare and Family Affairs;164–198.

43. Jeong JH, Kim SH. A survey of dietary behavior and fast food consumption by high school students in Seoul. J Korean Home Econ Assoc. 2001. 39:111–124.

44. Åstrøsm AN, Rise J. Young adults' intention to eat healthy food: extending the theory of planned behavior. Psychol Health. 2001. 16:223–237.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download