Abstract

With the increase in multi-cultural families, Korea is seeing a rapid increase in immigrated housewives, who are closely related to food culture. However, studies for the diet of multi-cultural families, which is most closely related to our lives have not been sufficiently researched. With this background, this study conducted research for immigrated women nationwide about food cultures to provide the possibility which Korean food culture would be developed harmoniously with various foreign food cultures. In this study, the immigrated women seemed to have adapted to Korean food culture quickly, but they showed differences according to some conditions like countries they are from and the time they have been in Korea. To achieve this, we need to conduct consistent and in depth studies for food cultures in multi-cultural families so that we can make healthy development in food culture, harmonious with traditional Korean culture.

Dietary life itself shows how a nation has adapted to the specific region where the nation is located for thousands of years. Therefore, it is very helpful to know about the regional background of a country in order to understand a nation [1,2]. This means that a national dietary life is formed under social, economic and environmental influences within a country [3] and, at the same time, it is made through the interaction with other countries [4].

A national dietary culture is formed by integrating long existing traditional dietary patterns and food consumption patterns on a country's natural environment with newly introduced life style [5]. Food is closely related to human life as a part of culture. Dietary culture has evolved under the various factors, including regional, racial and religious differences [6]. Most nations preserve and maintain their own dietary culture, but they witness it changing continuously over time [7-9]. With the rising trend of globalization, foreign cultures and commodities are imported massively into South Korea. Through this expansion, Korean cuisine and dietary patterns are undergoing many changes today [10]. We may say that today we live in "one global community", but dietary habits still express notable local and cultural characteristics as well as a strong conservative inclination [11].

With the rising economic status of South Korea and the increasing of globalization, Korean wave, Hallyu, is gaining more and more popularity among people in the world. Hallyu was first mentioned in the 1990s and the term meant that 'Korean wave was flooding into the society'. Since then, Hallyu has been frequently used in order to refer to the boom of Korean pop culture. In particular, the term means that Korean TV dramas, fashion and music are gaining popularity among people in Asian countries such as China, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Vietnam and Thailand, and especially among the youth of these countries [12,13]. In Korea, the number of foreign workers and foreign wives who are married to Korean men has risen sharply. According to data from Statistics Korea 2009, the number of interracial marriages has grown steadily since the 1990s and has reached over 10,000 per year in 1995, 24,776 in 2003, and finally showed a dramatic increase of 36,204 in 2008 [14]. In this situation, exchanging traditional foods among nations helps to promote the mutual understanding and cultural exchange among nations [7,15-17].

In terms of dietary attitudes and dietary behaviors of immigrant wives, Kuak [18] said that most foreign wives who married Korean men prepared meals, considering their spouses and parents-in-law first, and that they chose food based on taste and volume rather than nutrition. According to the research of Jang [19], the proportion of people who answered, "I sometimes experienced shortage of food because of financial difficulties" was highest when they were asked about their dietary life patterns. This means that immigrant wives' families are likely to be low-income class. Lee [20] said that the longer immigrants stayed in Korea, the more they felt responsibility for their family and the more they were stressed. Immigrant wives were under stress and the fact of being under stress put negative effects on the condition of nutrition, eating habits and health of them. Kang [21] reported that immigrant wives experienced cultural difference in Korean cuisine and dietary patterns for the first time when they started to adapt themselves to Korean society. Most of them have difficulty with taste of food, recipes, groceries and dietary patterns which are different from their home country. As they stay longer in Korea, however, they become accustomed to Korean food culture much easier than to any other different cultural areas.

For research, the questionnaires were distributed to 600 immigrant wives of 37 multi-cultural centers of the nationwide YWCA and 443 survey questionnaires, which were answered completely, were used. For two months, from February 25th to April 22th 2009, well-trained researchers for this questionnaire visited multi-cultural centers or questionnaires were sent out by post. Researchers distributed questionnaires, which were given in five different languages such as Korean, English, Chinese, Japanese and Vietnamese. The questionnaires were explained in detail before letting immigrant wives complete them.

The research examined home environmental factors of those surveyed and used multiple choice question type in which immigrant wives chose two mostly used food products while cooking. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANEX)'s Dish-based Food Frequency Questionnaire was restructured appropriately to the study and recognition of Korean cuisine and food products was investigated [22]. Moreover, the study examined whether immigrant wives recognized BEST 12 dishes and knew how to cook them, the manner of table setting. BEST 12 dishes were out of "100 wonderful Korean cuisine", which were selected by Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. Finally, the frequency of eating their homeland's food, the way to cook the food, the reasons why they transform the way to cook the food, differences in table setting between their motherland and Korea, and difficult parts of Korean table manners among immigrant wives were examined.

The data collected for the analysis of the research results was handled by using SPSS version 14.0 k. First, basic statistics (frequency, %, ranking, average, and etc) were calculated based on the responses from those surveyed on each item of the questionnaire. Second, cross tabulation analysis (Chi-square statistics) and one-way ANOVA were conducted on the frequency and average of the questionnaire items, which require verifying awareness-difference among groups.

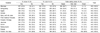

The findings on the General factors of those surveyed are shown on the Table 1. The largest number of those surveyed was from Vietnam, followed by China, the Philippines, Japan, Russia, Uzbekistan, Mongol and others. In terms of the length of residence, more than 60% of the total people questioned resided in Korean for less than 1 year and between more than 1 year and less than 3 years, followed by between more than 3 years and less than 5 years, between more than 5 years and less than 10 years, and more than 10 years. Thirty-two people answered that they lived in Korea for more than 10 years.

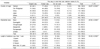

The findings on food products used in cooking based on the general factors are shown on the below Table 2. There were noticeable differences depending on the country of origin (P < 0.01) and residential area (P < 0.05) while there were not obvious gaps depending on the length of residence among immigrant wives. In particular, the research showed the high level of use of grains in all of the countries of origin, while in terms of meat only four Japanese housewives (6.35%) said that they use meat, which was a significantly low level. Fish was highly used among housewives from Southeast countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines where people eat seafood frequently.

The awareness level of foods depending on the country of origin is shown on the below Table 3. In terms do grain, there were noticeable distinctions among immigrant wives from different countries in the way they recognize rice (P < 0.05), barley/multigrain (P < 0.01), ramen or instant noodles (P < 0.01), noodles (P < 0.001), rice cake (P < 0.01). In terms of barley/mixed grains, females from Southeast countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines showed low level of awareness because those countries mainly plant rice. In terms of noodle, South Korean noodle, which is made of flour, was not well known to the females from Vietnam, for whom noodle is staple food along with cooked rice and both of them are made of rice [23].

In terms of meat, there was a clear distinction in terms of beef (P < 0.05), but there were almost no differences in terms of chicken and pork. South Asian countries including Vietnam and the Philippines showed lower level of awareness than Japan and China. This seems that the belief on doctrine of reincarnation and the idea of charitable deeds in South East Asia's Buddhist society has affected the Buddhists' awareness of meat. In particular, the lowest level of awareness of beef in South East Asian countries demonstrates that people do not kill water buffalos recklessly, which are indispensible animals for farming, compared to common livestock such as chickens and pigs. In other words, pigs, which were started to be raised 3,000 B.C. at the latest, have been an important main source of meat in tribal society in jungle and farming areas from the beginning, except Islamic regions [24,25].

In terms of vegetables, there was obvious differences in terms of raddish (P < 0.01) and red pepper (P < 0.01), unlike Chinese cabbage. In particular, most immigrant wives answered that they knew Chinese cabbage cuisine on the questionnaire. Chinese cabbage is highly recognized among them because it is grown and cooked in Vietnam, Philippines, China and Japan.

The findings on the recognition of Korean cuisine, possibility of cooking Korean food, and table setting styles are shown on the Table 4. According to the results, most immigrant wives answered that they knew all Korean cuisine on the questionnaire. Therefore, Korean cuisine is highly recognized among them. Bae and Jinlin [25] discovered that kimchi, bibimbab and bulgogi gained higher level of awareness through the survey on Korean food among foreigners residing in the U.S. This result shows again that bibimbab, kimchi, bulgogi, samgyetang, and kimbab enjoy higher level of awareness over 80% among Korean food. However, many of them answered that they could not cook the Korean cuisine. Seo et al. [17] found that students with cooking experiences of Korean food showed higher level of preference for Korean food than those without the experiences through the research on Korean Food Preference and the Improvement of Korean Restaurants for Japanese and Chinese Students in Korea. Han [26] found that most immigrated housewives had little confidence in their Korean food cooking skills, showing that only 17.9% of the respondents said their skills were "very good" and "good", meanwhile 41.1% said "not good" and "almost poor" through the research on Korean food cooking skills of foreign housewives. In terms of table setting, the results display that foreign wives who married Korean men understand each form of staple, side dish and snack well and use the different forms of food appropriately.

The findings on the frequency of eating their own national food are shown on the Table 5. There were obvious differences depending on the country of origin (P < 0.01), residential area (P < 0.01) and the length of residence (P < 0.01). The number of immigrant wives who answered that they eat their own national food once a month was highest, followed by once a week and almost never. Han [26] found that 26.8% of immigrated housewives enjoyed their own national dishes 1~3 times or not at all per month through the research on the frequency of taking their own national food among foreign housewives. Jang [19] found that the percentage of immigrated housewives who eat their own national food was only 3% for breakfast, 8% for lunch and 13% for dinner through the study on Dietary life of Female Marriage immigrants. This study reveals that the frequency of eating their own national food of foreign housewives is strikingly low.

The findings on the way to cook their own national cuisine among immigrant wives are shown on the Table 6. There are clear differences depending on the country of origin (P < 0.01), residential area (P < 0.01) and the length of residence (P < 0.01). The largest number of those surveyed said that they cook their national food in transformed Korean style. The second largest number of them answered that they cook the food in their traditional way, followed by people who said that they do not cook their national food.

The reasons why they changed the way to cook their own national food are shown on the Table 7. There was a noticeable difference depending on the country of origin while there were no differences depending on residence area and length of residence. The reasons why they change the way to cook the food are, first of all, the difficulty of finding food materials, followed by family members' rejection to unique flavor or taste, rejection of family members to food products, and the impossibility of cooking in their own national manner. Already being displayed in Kuak [18] and Sim [27], this shows the importance of consideration and psychological support from other family members when foreign housewives adapt to Korean culture. In the research of Jang [19], 40% of immigrated housewives responded they consider their husbands first and 28% of them said they think the entire family for the inquiry of whose preference they consider first when they prepare meals. Meanwhile, only 22% of respondents said they consider themselves first.

The findings on changes in table setting before and after immigration of wives to South Korea are displayed in the Table 8. Most foreign wives are used to spread out dishes on the table both before and after their immigration. In Japan, China and Thailand, people use spoons and chopsticks but in the Philippines, heavily influenced by Spain and America, most people use a knife and fork. The research, however, shows that 97.1% of immigrated housewives use spoons and chopsticks after their immigration. In addition, 86.9% of foreign housewives said they "sat on the chair to eat" before their immigration because people sit in the chair around the table to eat in Vietnam, the Philippines and China. However, 66.8% of foreign housewives responded that they "sit on the floor around the table when they eat" after their immigration into Korea. This demonstrates that immigrated housewives have adapted to Korean food culture well.

The findings on difficult Korean table manners among immigrant wives depending on the country of origin are shown on Table 9. There was a clear difference among wives in finding which Korean table manners are difficult to follow. Not to hold up a bowl with hands and to start to eat after the elderly started were revealed to be most difficult to get used to. In particular, Japanese people hold rice bowls with their left hands and eat with their right hands and they also bring their soup bowls to their mouths to drink soup. Therefore, more than 50% of immigrated housewives from Japan find it difficult "not to hold bowls with hands". 11.1% of immigrated housewives from the Philippines feel uncomfortable with "not using hands" because it is tradition to use hands when they eat and people still eat with their hands in some parts of the country.

The largest number of those surveyed was from Vietnam, followed by China, the Philippines, Japan, Russia, Uzbekistan, Mongol and others. In terms of the length of residence, more than 60% of the total people questioned resided in Korean for less than 1 year and between more than 1 year and less than 3 years, followed by between more than 3 years and less than 5 years, between more than 5 years and less than 10 years, and more than 10 years. Thirty-two people answered that they lived in Korea for more than 10 years.

The most used food product was grains with 32.3%, followed by vegetables, meat, fish and fruits. The number of those who answered that they have tried Korean food products or cuisine was significantly higher than that of those who said that they have never heard about or never tried any of Korean food. There was a noticeable difference among immigrant wives depending on their country of origin. In fact, higher number of wives from Vietnam or the Philippines answered that they have never heard about or never tried Korean cuisine and Korean food products than those from China or Japan. In addition, many of those surveyed answered that they could not cook 12 well-known Korean cuisines, except bibimbab. This result displays that some education is necessary. Meanwhile, immigrant wives understand the differences of each staple, side dish and snack, and applied them in an appropriate manner.

In terms of eating their own national food, the largest number of wives said that they eat the food once a month and it was as high as 22.3%, who said that they almost never eat their homeland's food. 46.7% of wives answered that they cook their own national food in transformed Korean style, 35.7% said that they cook the food in their traditional way and 14.2% said that they do not cook their own national food. The reasons why the wives put changes in their homeland's food are that it is difficult to find food materials, their family members reject the unique flavor, taste, even food products and the wives cannot cook the food as the way they did at their motherland.

In terms of table setting, 79.5% of the wives, who were used to placing dishes in time order before their immigration to South Korea, changed to spreading out dishes on the table without considering time order. 65.8% of the wives, who used table and sat on a chair, changed their lifestyle into sitting on the floor and 99.2%, who used fork and knife before immigration, became accustomed to using spoons and chopsticks. These findings display that immigrant wives were adapted well to Korean eating tools. Out of Korean table manners, immigrant wives found it difficult not to hold up bowls with hands, to eat after the elderly started to eat and to keep pace with others.

Based on these results, the author wants to make suggestions about the research of Korean cuisine and dietary patterns among multi-cultural family wives.

First of all, the education related to Korean cuisine and dietary patterns for multi-cultural family wives needs to consider differences such as the country of origin and the education should be continued. The results of the research showed differences in dietary life of immigrant wives depending on general factors such as the country of origin, the length of residence in Korea. Currently, Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family affairs offers customized service for multi-cultural families, which are designed to take account of life cycle of multi-cultural families. The system of this service needs to be applied to the education of Korean cuisine and dietary patterns as well. In fact, they are immigrant wives who manage food life of multi-cultural family and they need different dietary education at different time of their life from the moment when they come to Korea to the time when they form a family and rear a child.

In addition, although the results of the research showed that immigrant wives adapt themselves to Korean cuisine and food culture quickly, the frequency of eating their own national food was low because their family members disapprove. Therefore, not only education of Korean food culture for immigrant wives, but also comprehensive education of food culture for their children and spouses are essential in order to establish right dietary culture in multi-cultural family.

Finally, the research demonstrates that immigrant wives cook their own national food and Korean food in transformed ways. In the long term perspective, we might face new type of food culture with growing number of multi-cultural families. Therefore, we should develop our cuisine and dietary patterns in a right direction through persistent and profound study on dietary culture among multi-cultural families.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Joo NM, Kennon LR, Sim YJ, Lee KA, Jeong HS, Park SJ, Chun HJ. The Perception and preference of Americans residing in Korea for Korean traditional food. Journal of the Korea Home Economics Association. 2001. 39:19–23.

2. Park US. Factors of food adaptation and changes of food habit on Koreans residing in America. Journal of the Korean Society of Dietary Culture. 1997. 12:519–529.

3. Helen HG, Marjorie BW, Gail GH. Nutrition, Behavior and change. 1972. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

4. Carpo RH. Cultural anthropology; Understanding ourselves and other. 1993. 3rd ed. Guilford, CT: Dushkin publishing group.

5. Lim HS, Park MO, Lee SH. A study on the trends of food service culture and the direction for the development [master's thesis]. 2007. Seoul: Jangan University.

6. Kang DW. A Study for advancing into European market of Korean cuisine & the comparison between Korean cuisine culture and European cuisine culture. Korean J Culinary Res. 2003. 9:88–101.

7. Chung SS. Dietary change-food habits of Koreans in new haven [Doctor's thesis]. 1995. New England: The University of Connecticut.

8. Lee HK. Food habits of Koreans in United States [Doctor's thesis]. 1997. New York: New York University.

9. Sim YJ, Jung BM, Kim ES, Joo NM. A survey for the international spread of Korean food from the Korean residens in the U.S. Korean Journal of Food and Cookery Science. 2000. 16:210–215.

10. Jung YW, Lee SB. A Study on the application of multicultural cuisine to Korean food -focused on western preferences. Korean J Hosp Adm. 2008. 17:157–179.

11. Cha MA. Study on structural characteristics of Korea's food culture. Journal of Kyonggi Tourism Research. 1998. 173–190.

12. Cho Han HJ. Modernity, Popular Culture and East - West Identity Formation: A discourse analysis of Korean wave in Asia. Korean Cultural Anthropology. 2002. 35:3–40.

13. Park SK. International trade of Korean Wave [master's thesis]. 2010. Seoul: Ewha Woman's University;2.

14. Korea National Statistical Office. 2009 woman's life based on statistics - changes of international marriages. 2009. 9.

15. Han JS, Huh SM, Kim MH. American's acceptance of Korean foods. Journal of Resource Development. 1995. 14:93–99.

16. Han JS, Kim JS, Kim SY, Kim MS. A survey of Japanese perception of and preference for Korean foods. Korean Journal of Food and Cookery Science. 1998. 14:188–194.

17. Seo KH, Lee SB, Shin MJ. Research on Korean Food Preference and the Improvement of Korean Restaurants for Japanese and Chinese Students in Korea. Korean Journal of Food and Cookery Science. 2003. 19:715–722.

18. Kuak DH. Research to ingestion of food and an attitude from food and drink of Multicultural family [master's thesis]. 2008. Seoul: Wosong University;53–64.

19. Jang BS. A Study on dietary life of female marriage immigrants [master's thesis]. 2009. Seoul: Kyunghee University;20–21.

20. Lee SU. Association between stress, and nutritional and health status of female immigrants to Korea in multi-cultural families [master's thesis]. 2009. Seoul: Ewha Women's University;10–40.

21. Kang HJ. Immigrant Women's desire for expressing and preserving the mother culture and their identity [master's thesis]. 2007. Seoul: Sookmyung Women's University;46–47.

22. Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2007 KNHANEX's analysis of research on nutrition, Ministry of Health, Welfare and Family affairs. 2008. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANEXS).

23. Kim KT. A study on Vietnamese food culture. 1996. Southeast Asia Institute;129–168.

24. Cho HK. A study on Thai food culture. The Korean Ethnological Association. 2000. 4:205–233.

25. Bae YH, Jinlin Z. Marketing strategy for Korean restaurants in florida -through view of customers' preference, recognition and satisfaction. Journal of Food service Management. 2003. 6:85–100.

26. Han YH. Influential factor on Korean dietary life and eating behaviour of female marriage immigrants [master's thesis]. 2010. Seoul: Hanyang University;54.

27. Sim YH. The adoption process and transnational identity of international marriage women. 2008. Women's Institute of Hanyang University.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download