Introduction

Subjects and Methods

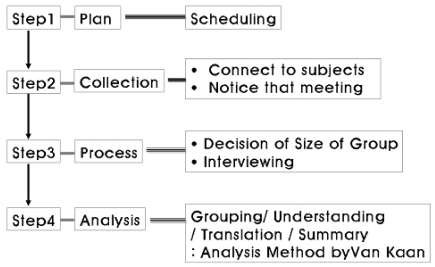

Study design

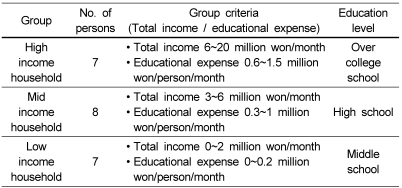

Selection of study participants

Study procedures

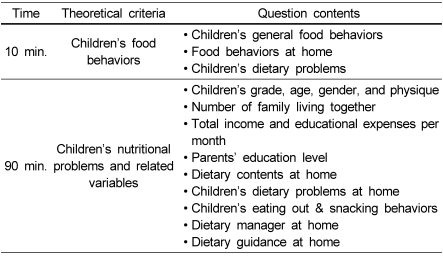

Preparation before interview

Interview process

Trial discussion before interview

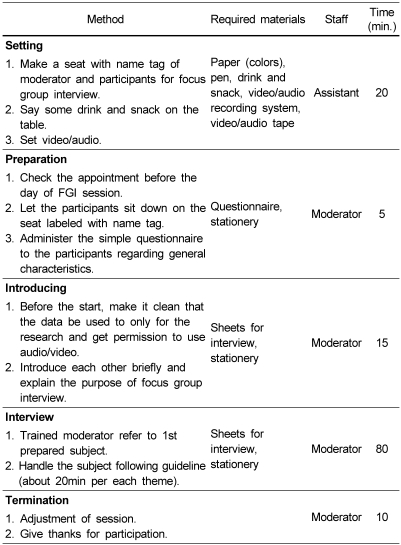

Performing interview

Preparation

Introduction

Discussion

Opening questions: Participants for the discussion introduced themselves. Their names and ages, number of children, and genders and grades of their children were introduced. It took about 10 minutes.

Introductory questions: Topics for discussion were introduced and then thoughts related to those topics were induced. Questions were made of what participants could find clues for their opinions by inducing first impression of participants on the topics of brainstorming.

Transition questions: Conversation was induced by important questions leading to the study. Another person's opinion on the topic was understood through these questions and participants were asked for their experiences in relation to the topic.

Key questions: More time was provided to these questions than to other questions so that participants could have enough time to talk about their thoughts or experiences.

Ending questions: When the discussion on related topics were finishing, the moderator arranged opinions generated from the discussion on related topics and confirmed participants for additional information or missing points.

Data analysis

All data obtained from the process of focus interview, that is, all data including verbal and non-verbal interaction used by participants in the focus group discussion were transcribed. In addition, the conversation of participants, responses and facial expression and attitudes of other participants during the conversation were recorded in detail. Transcribed data were copied and examined for the confirmation of important information after the original copy was saved.

Open coding was performed to search themes in all interview contents. Themes for interview content were selected and the criteria was established and then classified by themes. For the reliability of content analysis, investigators performed cross-validation of each other for the classification by themes for coding results.

Axial coding was performed to decide category and subcategory by the relationship among themes established in Step 2. Each theme was understood for the category largely relevant to the study problem, and further relationship among themes were searched to decide category and subcategory.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download