INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization's dietary guidelines emphasize that a sufficient vegetable intake can decrease the occurrence of noncommunicable diseases, such as diabetes, heart disease, and cancer [

123]. Furthermore, a sufficient vegetable intake has been emphasized as an essential aspect in most countries' dietary guidelines [

4]. In line with this trend, the Korean government is attempting to increase the vegetable intake of its citizens. One example of this is its Health Plan 2020, which includes the goal of having 50% of the population over six years of age consume more than 500 g of vegetables and fruits each day [

5]. However, despite such a plan, daily vegetable intake remains less than the recommended amount (the current daily average vegetable intake is approximately 294.2 g). In addition, the current average vegetable consumption of Korean adolescents (aged 12-18 years) is approximately 216.1 g, a level that has remained more-or-less constant in recent years [

6].

A possible reason for the low consumption of vegetables by adolescents is the current popularity of Western foods and food practices, involving an increased intake of processed foods and regular dining out, in Korea. Adolescents also prefer animal products or fast food over plant-based foods such as whole grains and vegetables [

78]; thus, the implementation of nutrition intervention to encourage adolescents to increase their vegetable intake is needed.

Food choices or preferences in childhood or adolescence can continue into adulthood; the food choices one makes in adolescence directly affects those in adulthood, when one becomes independent and responsible for managing their own diet [

910]. Thus, from the long-term perspective of improving national health and quality of life, it has become clear that adolescents require nutrition education, not only from educational experts but also from nutritionists.

Despite this need and the importance of nutrition education to promote vegetable intake, only 21.3% of adolescents received nutrition education or counseling in 2015; however, 44.8% of children aged 6-11 years received such information [

6]. In Korea, the factors regarding vegetable consumption in school-age children and adults has been previously reported [

111213], and self-efficacy has been proposed as a significant factor that could increase the vegetable consumption of those subjects [

1113]. However, there is a lack of studies with a psychological perspective that are based on nutrition education theory and that consider factors that influence adolescents' vegetable intake.

People's dietary behavior is a result of interactions among various influencing factors, such as individual and socio-cultural factors [

14]. Hence, identifying factors that influence behavioral changes is critical for the implementation of nutrition education for adolescents. By examining such influencing factors, primary targets and learning experiences that can be implemented as part of educational strategies can be efficiently designed.

The stages of change (SOC) construct relates to the stages of behavioral change proposed in the transtheoretical model (TTM), a model in which self-change in behavior is a process with five stages. The stages within the SOC construct are precontemplation (PC), contemplation (C), preparation (P), action (A), and maintenance (M). In addition, the TTM includes 10 change processes and two determinants for change: 1) decisional balance based on the pros and cons of change, and 2) self-efficacy. The behavioral change process can also be subdivided into cognitive and behavioral changes. The initial stage in a behavioral change tends to focus on cognitive changes, whereas the later stage focuses on behavioral changes. It has been proposed that behavioral changes, or strategies for such change, should be applied differently in these two stages because there are differences between socio-psychological and behavioral stages that depend on the health behavior in question [

314].

Numerous nutrition- and health-intervention studies have exclusively applied the SOC construct without considering the TTM's “processes of change” [

14]. The SOC construct provides for the implementation of more effective nutrition interventions by providing categories that classify subjects according to their psychological states and by providing information on the psychological and behavioral differences between people who practice dietary behaviors and those who do not, which is important in nutrition and health interventions [

31415]. However, obtaining exclusively socio-psychological elucidation of the process of self-change of a behavior has limitations associated with establishing strategies for the behavioral change. Thus, exploring behavioral change strategies by applying a structure based on the theory of planned behavior or social cognitive theory (SCT), which predict behavioral changes or their influencing factors, is required [

31415].

In this study, the SCT construct was applied to analyze the factors influencing vegetable preference. SCT is most extensively used in nutrition intervention and health promotion programs, and it has also been widely used in studies examining factors related to increasing vegetable intake in children and adolescents [

1416]. SCT suggests that an individual's current dietary behavior results from complex interactions between personal, behavioral, and environmental factors, and it provides a framework that allows the user to identify the determinants affecting a behavioral change. This enables the design of nutrition education that makes behavioral changes feasible.

According to Birch [

17], food preferences imply the selection of one of many items based on “liking” the selected item. Although food preferences are influenced by innate factors, they can be altered by learning and experience. Therefore, proposing educational strategies that are based on the elucidation of factors influencing vegetable preference is likely to contribute to an increase in vegetable consumption.

The purpose of this cross-sectional study is to suggest a stage-tailored education strategy for promoting vegetable consumption. This goal was pursued by exploring personal, behavioral, and environmental factors within the SCT components and identifying the SOC in vegetable preferences in adolescents.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects

This study was conducted in June and July 2014 on 1st- and 2nd-year high-school students from two schools located in the city of Gyeongsangnam-do, Korea. Four-hundred students participated in the study. The study conductor explained the study content to each class, after which the students completed self-administered questionnaires. Of the returned questionnaires, data from 398 (boys: 192, girls: 206) were used in the analysis. The study proposal was approved by the institutional review board at Changwon University (No. 1040271-201409-HR-013).

Measures

Stages of change

Questions aimed at evaluating the stages of behavioral changes related to vegetable intake were designed based on previous studies [

1318]. The first question was “Do you eat various kinds of vegetables?.” Subjects who responded “No” were questioned further, as follows; those who responded “No, I do not intend to eat various kinds of vegetables” to the question “Do you intend to eat various kinds of vegetables from now on?” were classified as PC, while those who responded “No, but I am planning on eating various kinds of vegetables in the near future (within six months)” were classified as C, and those who responded “Yes, I will eat various kinds of vegetables very soon (within one or two months)” were classified as P.

Returning to the responses to first question, “Do you eat various kinds of vegetables?,” those who responded “Yes, I began eating various kinds of vegetables recently (less than six months ago)” were classified as A, and those who responded “Yes, I have been eating various kinds of vegetables since I was child” were classified as M (

Fig. 1).

Social cognitive theory constructs, vegetable preference, and health-promoting dietary practice

The questionnaire variables consisted of personal (outcome expectation, self-efficacy, affective attitude), behavioral (knowledge), and environmental (vegetable accessibility at home and school, parenting practice) factors, which were used to determine the most useful factors across the SOC. Vegetable preference was assessed by using a scale that determined the degree to which an individual participant liked each of 23 different kinds of vegetable (determined by using a four-point Likert scale). To evaluate health-promoting dietary practice, additional sub-items were added, consisting of 18 items based on dietary guidelines for Korean adolescents. Detailed information on SCT variables, vegetable preference, health-promoting dietary practice, and general characteristics has been reported in a previous study [

19]; however, in this study, the sub-items relating to vegetable accessibility at school consisted of “Vegetable dishes are served in the lunch menu at school,” and “I can eat more vegetables at lunch time if I want.”

Statistical analysis

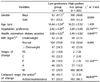

All data were analyzed by using SPSS 21 version (IBM Corporation), and the significance level was set at P < 0.05. In order to determine differences in vegetable preference variables, a cluster analysis (K-mean method) was conducted to divide subjects into subgroups depending on their preferences, and after considering the number of students within each subgroup, two main groups were chosen. In addition, in terms of SOC assessment, because there were few subjects in the PC, C, and P stages, each stage was subdivided into a pre-action stage and action/maintenance stages (A/M). For each group, frequency distributions were used to describe gender, body mass index (BMI), and SOC data for the categorical variables, whereas age, vegetable preference, the SCT variables, and health promotion dietary practice as continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations. The significance of the differences in measured variables between two vegetable preference groups was examined using t-test and chi-squared tests. Stepwise multiple-regression analysis was used to examine the determinants of vegetable preference among SCT variables over the subdivided SOC. In those regression analyses, the dependent variable was vegetable preference, which was applied as a continuous variable.

DISCUSSION

This study was conducted to elucidate the determinants that affect the vegetable preference of adolescents to suggest useful nutrition education strategies. In this study, we applied SCT components and SOC in order to establish stage-tailored educational strategies that can contribute to increasing the vegetable intake of adolescents.

Despite the fact that no significant association between vegetable preference and BMI was detected in our study results, a sufficient vegetable intake has been reported to have positive health effects, as it reduces the incidence of obesity and increases anti-oxidative effects in adolescents [

2021]. Consequently, promoting vegetable preference among adolescents as a means of encouraging their sufficient vegetable intake will contribute to health improvements in adolescents.

In this study, analyzing the stages of behavioral changes in the subjects in terms of vegetable preferences showed that most subjects in the HPG were in stage M (80.9%). However, in the LPG, although the percentage of subjects who were in stage M was lower (29.5%) than that in the HPG, it was higher than the percentages of the other stages within the LPG. The results of comparing SOC by gender showed similar trends, regardless of gender. Previous studies have shown that subjects in the M stage are likely to have higher vegetable intake than subjects in other stages [

318]. As there were significant differences in SOC between the groups, analyzing SCT factors related to SOC differences between groups can help develop a stage-tailored strategy suitable for enhancing vegetable intake.

When the SCT components were compared in each group, subjects in the A/M stage in the LPG were found to have higher mean scores in self-efficacy, affective attitude, vegetable accessibility at home, and vegetable accessibility at school than LPG subjects in the pre-action stage. This result showed that certain exposure factors, such as accessibility, could be important factors affecting vegetable preference in the initial behavioral stage. Subjects in the HPG showed significant differences in the mean values of self-efficacy, affective attitude, and parenting practice between A/M and pre-action stages, which indicates that, despite the independent tendencies of adolescents, parents may still be able to encourage adolescents to consume more vegetables in the later behavioral stage. In addition, this result reveals a typical characteristic associated with low self-efficacy and affective attitudes in the pre-action stage, that is, in each stage, those two factors foster the capability to execute behavioral change [

14]. In TTM, marked movements occur across each stage, and they depend on the motivation and self-efficacy of the subjects in relation to performing specific behaviors [

14]. Acting on motivation is decided by self-efficacy, which reflects the confidence to perform a behavior and which is promoted by cognitive behavioral processes, and evaluating pros and cons [

314]. Expecting a more positive affective effect from having a sufficient vegetable intake will contribute to progression to the M stage, as this effect increases the motivation of a subject to improve vegetable intake. As mentioned above, subjects in the A/M stage in the LPG had high scores in self-efficacy and affective attitude, which suggests that, compared to other factors, self-efficacy and affective attitude can be major influencing factors for increasing vegetable intake in adolescents, which has also been shown in other studies [

1113,

22]. In addition, Van Duyn et al. [

23] reported that self-efficacy and affective attitudes were the most important factors in increasing the consumption of vegetables and fruit.

As noted above, the subjects in the LPG's A/M stage were considered more likely to be exposed to vegetables at home and school than LPG subjects in the pre-action stage. Adolescents who attempt to design their own dietary environments at home or at school may face limitations. For example, the dietary environment at home has a close association with the diet patterns of adolescents, and vegetable accessibility has a significant correlation with vegetable intake [

2224]. In order to increase vegetable intake, strategies to increase the exposure, availability, and accessibility of vegetables in the environment surrounding an adolescent, including both home and school, are required.

Investigating the influencing factors for each of the subdivided SOC using stepwise multiple-regression analysis revealed differences between SCT components in the behavioral stages. In addition, the results suggested that a nutrition education strategy should be developed differently depending on the subject's SOC. Subjects in the pre-action stage can have their vegetable preference affected through self-efficacy and parenting practice, suggesting that the controlling feeding style may inversely affect vegetable preference in the initial behavioral stage. Savage et al. [

25] have suggested that a parentally restrictive feeding practice tends to be associated with negative eating behavior outcomes.

In subjects in the A/M stage, outcome expectation, affective attitudes, and accessibility at school were determinants of improving vegetable preference. When group differentiation was not included, affective attitudes, self-efficacy, and vegetable accessibility at school were included as determinants for improving vegetable preference. With regard to determinants that have significant effects on adolescents' vegetable preferences, an affective attitude is the predominant factor, and accessibility at school is another major determinant. Neumark-Sztainer et al. [

26] proposed that taste preference and the availability of fruits and vegetables at home were determinants of adolescents' vegetable and fruit intake. An affective attitude is based on feeling, and feeling and emotion regarding vegetable intake basically originate from direct experience of the taste of vegetables, thus our study results support the proposal by Neumark-Sztainer et al. [

26]. In addition, Neumark-Sztainer et al. [

26] also suggested that adolescents' vegetable intake is affected by their parents and by the home environment, even though adolescents seem to make food choices independently, outside of their parents' influence. In Korea, adolescents spend a large amount of time in school (especially high-school students, who arrive early in the morning and often attend self-study sessions at night), and eat at least two meals at school. Thus, vegetable accessibility at school is likely to have an important role in increasing adolescents' vegetable intake. Therefore, providing positive experiences with vegetables, in addition to frequently providing vegetables in school meals, can constitute critical strategies for increasing vegetable intake in adolescents.

Self-efficacy has been mentioned in several previous studies as being the most important factor in encouraging adolescents to practice health-promoting dietary behavior [

101113222627]. Our study results also showed that self-efficacy is a significant factor in terms of vegetable preference and intake. In order to increase self-efficacy, establishing a strategy for reviewing factors the impede vegetable intake behaviors and increasing confidence in executing vegetable intake-related behaviors is required. In terms of enhancing self-efficacy and affective attitude, behavior change strategies with “reframe perceptions of barriers and confidence in order to facilitate the performance of behaviors” and “promote reflection on anticipated emotions” have been suggested [

14].

Although this study has strengths related to the application of SCT and SOC constructs as theoretical frameworks for examining factors influencing increases adolescents' vegetable intake, there are limitations to the research. First, as the actual consumption patterns and the level of subjects' vegetable intake at home and school were not analyzed, objective evidence of a subject's stage of behavioral changes could not be obtained; hence, correlations between SOC, SCT, and the levels of vegetable intake should be investigated further. In addition, the socioeconomic backgrounds of the subjects were not assessed. Socioeconomic background is a factor that influences what and how the subjects eat and, therefore, can have an important effect on a subject's dietary habits [

14].

The importance of nutrition education related to vegetable preferences in adolescents has been emphasized in previous studies [

1923]. In order to impart an effective education, not only should information be provided, but also various educational strategies such as encouraging motivation, improving behavioral abilities and skill, and providing opportunities to participate should be provided; such actions are required for adolescents to acquire and practice healthy dietary behavior [

14]. Based on the analysis of adolescents' vegetable preferences and the SCT components in each stage of their behavioral changes, affective attitudes, vegetable accessibility at school, and self-efficacy were observed to be the predominant determinants in this study. Furthermore, the results suggest that school-based nutrition interventions that promote positive feelings or emotions toward vegetables and strategies that expose adolescents to positive and direct experiences with vegetables and enhance their confidence in behavioral change, can effectively contribute to an increase in vegetable intake as well as a broadening of vegetable preferences in adolescents.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download