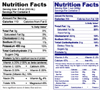

Since 1972, the content of major nutrients and the percent one serving provides of a standard reference value based on the recommended dietary allowances (RDAs) of the Food and Nutrition Board (FNB) of the National Academy of Sciences (

Federal Register, 1973) has been displayed on food products in the United States (

Fig. 1). When the U.S. FDA initiated voluntary nutrition labeling, it stated that the inclusion of a daily dietary intake standard was to enable consumers to determine the contribution a food would make to their daily intake of nutrients (

Federal Register, 1972). At the time, nutrition scientists from the American Institute of Nutrition proposed standards that were based on recommended intakes, recommending the use of the adult male standard (

Federal Register, 1972;

Federal Register, 1973). The current label values, the U.S. RDAs, were derived from nutrient recommendations from the seventh edition of the

Recommended Dietary Allowances published in 1968 (

National Research Council, 1968) for most nutrients.

It has always been recognized that a single set of values could not be considered reflective of the specific nutrient requirements of each consumer; however, the values are useful for comparing relative nutrient contributions of items so labeled to the overall diet (

Pennington & Hubbard, 1997). The U.S. FDA, following the expert advice previously mentioned, proposed that the U.S. RDAs be based on the following (

Federal Register, 1993): the highest 1968 RDA value for each nutrient for non-pregnant, non-lactating persons ages 4 y and older

1). This results in the DV being greater than the recommended intakes (RDAs) for some of the age and gender groups in the population (

Pennington & Hubbard, 1997). With the passage of the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990 (NLEA) by the U.S. Congress, it became mandatory for almost all processed foods to display the Nutrition Facts panel (

Federal Register, 1993). In 1994, with the passage by Congress of the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act, the same format was developed for dietary supplement ingredients.

As Korean nutritionists are aware, in 1994, the Food and Nutrition Board initiated a process to expand the RDAs to include other reference values (

Federal Register, 1973). Since 1997, periodic reports from the FNB have established multiple categories of nutrient reference values, dietary reference intakes (DRIs), which include not only recommended intakes, but also additional reference intake values for both the U.S. and Canada (

IOM, 1997). In 2002, Health Canada and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requested specific guidance from the FNB on how to appropriately use the DRIs in nutrition labeling. In November 2003 the IOM/FNB Committee on Use of Dietary Reference Intakes in Nutrition Labeling issued its report (

IOM, 2003).

IOM recommendations for incorporation of the dris into nutrition labeling

The IOM committee recommended two fundamental changes in the basis for the DV:

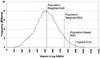

that the %DV be based on the estimated average requirement (EAR), one of the new DRIs, rather than the RDA (which continues to be one of the categories of DRIs); and

that the EAR used should be a population-weighted mean of EARs, rather than selecting the highest value of an EAR for any age-and-gender group.

The recommendations were also to use a population-weighted average for the Adequate Intake (AI) for nutrients for which no EAR was established (See

Fig. 2 for the quantitative representation of the relationship of these nutrient reference values).

The reasoning for these recommendations to use the EAR and base it on a population-weighted average is as follows:

"The best point of comparison for the nutrient contribution of a particular food is the individual's nutrient requirement. It is almost impossible to know the true requirement of any one individual, but a reasonable estimate can be found in the median of the distribution of requirements, or the EAR…. The EAR represents the best current scientific estimate of a reference value for nutrient intake based on experimental and clinical studies that have defined nutrient deficiency, health promotion, and disease prevention requirements….

"A level of intake above or below the EAR will have a greater likelihood of systematically over- or underestimating an individual's needs. The RDA is derived from the EAR and is defined to be 2 standard deviations above the EAR on the nutrient requirement distribution curve. Therefore the RDA is not the best estimate of an individual's requirement. For these reasons the committee recommends the use of a population-weighted EAR as the basis for the DV when an EAR has been set for a nutrient. This approach should provide the most accurate reference value for the majority of the population (

IOM, 2003)."

Of the 39 nutrients that have one or more of the categories of DRIs in the U.S./Canada reports, 19 nutrients have EARs; for 15 other nutrients, no EAR could be established, and thus no RDA was set. For this group, another category of DRIs representing a recommended intake, the adequate intake (AI), is provided for use in dietary guidance until such time as an EAR (and consequently, an RDA) may be established. For these nutrients, the IOM report recommends that the AI be used until an EAR is developed in future revisions of the DRIs.

Importance of determining the purpose of nutrition labeling

When multiple reference values are available, before evaluating which value is the most scientifically appropriate value to select, it is important to clearly articulate the purpose of nutrition labeling. There are many purposes for which nutrient reference values are needed; the one to which the current NRVs for Codex have been ascribed is to have values to be used in nutrition labeling. If the purpose and intent of nutrition labeling were limited to being able to compare the nutrient composition of one food item with another (for example, low fat milk with skim milk), then there is no need for the amount of a nutrient in a product to be given in terms of a reference value related to nutritional requirements or need. This is what is done when the amount is given per standard unit, such as 100 g. Based on the most recent discussion at the Codex meeting of the CFNSDU, it appears that there is an expectation that the values chosen are to be scientifically based and related to requirements. Given that now there are multiple reference values developed both here in Korea, in the Netherlands, in Australia/New Zealand, in the European Union, etc., it must be determined which category of values should be used and how should they be integrated. I see this as the charge to the Electronic Working Group which is coordinated by the Republic of Korea.

Given, then, that the NRVs are to be used for labeling, the question is what level of intake should be used? Five possibilities have been proposed: it can be

the average requirement of the average individual (the population-weighted EAR),

the average requirement of individuals in greatest (the highest EAR/day for any age/sex group)

the recommended intake of the average individual (the population-weighted RDA),

the recommended intake of 97.5% of the population (the population-based RDA), or

the recommended intake of individuals in greatest need (the highest RDA/day for any age/sex group).

If the purpose of nutrient labeling is to provide one reference value that is statistically the closest to the nutrient requirement of any given individual above the age of 3 years, then the EAR is the best reference value from which to derive an NRV, and to be closest to the average requirement, it should be a population-weighted mean of EAR values. Approximately half of individuals will require more, half will require less, and thus it is the closest number, on average within the population, to an individual's requirement.

If this is chosen, then, the actual NRV used within a country would vary depending on the age distribution of the country (as for many nutrients age is a surrogate factor for varying needs due to body size or gender), and thus what might be appropriate for a country which has a majority of individuals over the age of 30 years might not be relevant for a country where the majority were under 30 years.

The second approach, the highest EAR for any age or sex group, would give be a somewhat higher value than the population-weighted EAR in countries where more of the population was young, and would thus be more protective of adults for whom the EAR is typically larger for older individuals who are taller and have larger body sizes than children.

The third approach, the population-weighted RDA, would be a higher value than the population-weighted EAR, and would provide for a value which would meet the requirements of more individuals in the population.

If the goal were to cover the needs of almost all individuals in the population (a set percentage, perhaps 97.5%, or 2 standard deviations above the median requirement), then the population-based RDA would be used. This would meet the needs of all but a defined percentage.

The fifth approach, basing the NRV on the highest RDA for any age or sex group, would provide an amount that would meet the needs of all in the population, regardless of age/size.

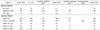

Thus the choice of approach depends on the purpose of nutrition labeling: if the intent is to provide an intake value which will meet the requirements of almost all who will be using the label in the population, then that value is the highest RDA or the population-based RDA. If the intent is to provide an intake value which is statistically the closest to the true average requirement of the population, then the population-weighted EAR is statistically the appropriate value. Population-weighting results in the requirements of fewer individuals in the population being met by the NRV than if the highest value had been chosen, regardless of whether it is based on the EAR or RDA (

Fig. 3).

When the highest RDA is chosen as the basis for the NRV (as has been past practice in the U.S.), the requirements of only 2-3% of one sub-group in the population (the one with the highest RDA) would not be met, thus covering the greatest number of individuals; however, if a population-weighted mean of RDAs is chosen, then more people in the population would not be covered, as the value would be less than if population-weighting had not been applied (and if a population-weighted EAR is used, the requirements of a vastly larger group within the population would not be met).

An additional issue is the use of a population-weighted Adequate Intake (AI) for nutrients for which there was not an EAR or RDA. The AI is defined as an amount that will meet the needs of all individuals in the specific age/lifestage group for which it is established, and thus it is similar to the RDA from the 7th edition upon which nutrient labeling in the U.S. has been based. If used as the basis for an NRV along with an EAR based approach, a mixture of reference values, derived in different ways would result: e.g., in the U.S. while the AI-based NRV for calcium would be 1,091 mg, the population-weighted EAR for vitamin C would be 63 mg, an amount thought to be inadequate for a portion of the population, particularly those who smoke10.

Examples of how the values change depending on the approach taken are given in

Table 1, representing data for the U.S. population using the U.S. DRIs.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download