Abstract

This study was to investigate utilization status of internet, health/nutrition websites among children, and to assess the needs for developing nutrition websites and education programs for children. The survey questionnaire was administered to 5-6th grade students (n=434) at two elementary schools. About 32% used the internet every day while 19.5% used it whenever they needed, showing significant differences in internet usage by gender (p<0.01). Although the subjects used the internet frequently, those who used health/nutrition websites were 23.3%. The purpose of using these sites were mainly 'to obtain health/nutrition information' (55%), 'to get information regarding weight control' (17%). Fifty-six percent of the users were satisfied with the nutrition websites, but only 30% said that they were helpful. The preferred topics in developing nutrition websites were assessment of obesity, exercise methods, weight control methods, nutrition information (e.g., diet for stature growth), dietary assessment and food hygiene. Girls showed more interest in these topics than boys (p<0.05). For school nutrition education, girls showed more interest than boys in topics for cooking snacks (p<0.001) and selecting snacks (p<0.05). In nutrition websites, subjects wanted to have information and game/quiz, as well as getting information using Flash animation. The favorite colors for screen and text were slightly different by gender (p<0.01). In school nutrition education, 89.5% of subjects liked to have activities (e.g., cooking, exercise, game). They also liked materials using computers, video and internet than printed materials. If nutrition education was done at schools, subjects wanted to receive 5.7 times of education per semester on average (mean length: 42.6 min./session). This study suggests that nutrition websites and education programs for children should include the topics such as assessment of obesity or diet, weight control and special information (e.g., diet for growth) as well as general information. In designing nutrition websites and programs, methods including game, quiz, Flash animation and activities (cooking, exercise) could be appropriately used to induce the interest and involvement of children.

Despite the importance of nutrition for school-aged children, many studies revealed the inadequate nutrition and poor eating habits of elementary school students. According to the Korea NHANES III (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III), dietary intakes of children aged 7-12 years were deficient in calcium (consuming 68.7% of RI, recommended intakes) and potassium (consuming 54% of RI). In contrast, the intakes of nutrients such as protein and sodium were excessive, reaching more than 200% of the recommended level. About 17% of children aged 7-12 years consumed 30 or more percent of energy from fat, and 8.5% of them were categorized as over-consumers of energy and fat (Department of Health and Welfare & Korea Health Industry Development Institute, 2006). Eating habits of elementary school students are characterized by high percentages of those who skip breakfast, not eating diverse foods, frequent consumption of instant foods or fast foods, and having snacks high in fat or sugars (Chung et al., 2004; Kang et al., 2004; Park et al., 2006; Sung et al., 2003).

Nutrition education for children is valuable in changing nutrition behavior and promoting health, considering that adequate eating behavior formed in childhood would continue to later life. For nutrition education to be effective, education materials also need to be developed carefully by being tailored to the characteristics and needs of the target population. With the development of information technology, the use of the internet has become popular in this country. Those who use the internet reached 75% in 2006; for those aged 6-19 years, 98.5% used the internet (National Internet Development Agency of Korea & Ministry of Information Communication Republic of Korea, 2007). Her and Lee (2003a) reported that elementary school children used the internet mainly for playing games or for social interaction with friends. As most children use the computer and the internet, it might also be a valuable tool for nutrition education. Recently, the internet has become the important sources of nutrition information (Lee et al., 2002b). Providing nutrition information and education through internet has advantages in that it reaches large numbers of people without the constraints of time and space. Some nutrition websites for children were well-designed and developed (Her & Lee, 2002; Hyun et al., 2003), however, the needs for nutrition websites for children are thought to be increasing.

In addition to nutrition education through online, education at schools also can be done more actively, since the school provides the adequate environment to acquire and learn desirable eating behaviors for children. However, only a few schools implemented nutrition education in classrooms; instead, nutrition education was done through sending prints home, using bulletin boards and education at school lunch programs (Kim & Lee, 2003; Yoon & Lee, 2001). Park et al. (2006) reported that only 4.2% of nationally-surveyed schools performed nutrition education by dietitians in classrooms or during extracurricular activities. In implementing nutrition education at schools, lack of education materials or counseling skills were identified as major barriers in a survey with dietitians at elementary schools (Ahn et al., 2007). Compared to these, Pérez-Escamilla et al. (2002) reported that 56% of schools studied in the U.S. implemented nutrition education in classrooms.

Since school nutrition teachers started to work at schools since 2006, nutrition education will be increasingly implemented from elementary to high schools in Korea. Therefore, it is needed to develop nutrition education programs tailored to the needs of children. In addition, education materials should be carefully developed to help the nutrition educator implement the education programs more effectively and efficiently. Considering the fact that internet play a role as information sources while nutrition education materials are lacking in the fields, it might be feasible and effective to use nutrition websites in school nutrition education. In a previous study (Ahn et al., 2007), we examined the needs of elementary school dietitians for developing a nutrition information site for elementary children. The purpose of this study was to investigate the needs of elementary school children to obtain the baseline information for developing nutrition websites and education programs. More specifically, we tried to examine the utilization status of the internet, health or nutrition websites among children, and investigate the needs of children in developing nutrition websites and education programs. We also examined if these needs were different by gender. This study would provide valuable data in developing educational websites and programs that contribute to the nutritional well-being of children.

This study was a cross-sectional survey and was conducted during July and August, 2006. Subjects for this study were a convenience sample, and were recruited from two elementary schools located in Seoul and Uijeongbu, Kyungki-do, which are in the northwestern area of the Republic of Korea. These two schools were chosen since the school personnel allowed to do the study after being informed of the study purpose and procedures. Subjects were 5th- and 6th-grade students from 14 classes at two schools. The investigator met with the class teachers and explained the study purpose and the ways of administering the survey. Subjects were asked to participate in the survey, and responded to the questionnaire, following instructions of the questionnaire. Data were obtained from all of the 5-6th grade students, 465 students at two schools (205 from school A and 260 from school B). Data with many incomplete items were excluded, and finally data from 434 students were used for statistical analysis (93.3%).

The survey questionnaire was based on and modified from the previous studies regarding needs assessment for developing nutrition information websites for elementary schools or adolescents (Her & Lee, 2003a; Hyun et al., 2003; Kim & Yoon, 1999; Kim et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2002a). The survey questionnaire included items to measure general characteristics of the subjects, status of internet utilization, status of using health or nutrition information websites, needs assessment for developing nutrition websites and school nutrition education programs.

General characteristics included items regarding gender, grade, age, residence area, exercise frequency and degree of TV watching. Status of internet utilization was assessed by asking questions such as frequency and time spent on internet use and purpose and place of internet use. Based on the experience of using health or nutrition websites, subjects were asked to respond to different questions. For example, users of health and nutrition websites responded to the items such as degree of using those sites, purpose of using, satisfaction with the sites, problems of nutrition sites, and helpfulness of those sites. Non-users of health and nutrition websites were asked to check the reasons for not using, and intention to use the nutrition sites in the future.

To investigate the needs of children regarding what they want in nutrition websites, preferred topics and methods in developing nutrition websites were asked. Scales on preferred topics consisted of 21 items of nutrition topics including general nutrition, dietary assessment, childhood obesity, selecting snacks, and reading nutrition labels. Each item was rated on a 3-point scale ranging from 1 (not interested) to 3 (interested). Items to consider in developing nutrition websites, such as effective methods to deliver nutrition information in the websites, favorite colors (screen, text) and desirable period for site update, were also asked.

To examine the needs of children for developing school nutrition education programs, preferred topics were asked. Scales on preferred topics consisted of 15 items of nutrition topics, similarly to the items stated above. Each item was rated on a 3-point scale ranging from 1 (not interested) to 3 (interested). In addition, survey questionnaire included items regarding experience of nutrition counseling with dietitians, preferred education methods, preferred nutrition education materials, education frequency and length per each session that they want. After constructing the survey questionnaire, items in the questionnaire were examined in terms of understanding and were slightly modified in words or sentences.

Data were analyzed using the SAS program (SAS package Version 8.2). Descriptive statistics were used to examine the distribution of study variables. To investigate if study variables, including general characteristics, utilization status of internet, health or nutrition websites, needs assessment for developing nutrition websites and education programs, differ by gender, chi-square test was done for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables. Statistical significance was tested at α =0.05.

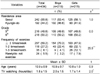

General characteristics of subjects are presented in Table 1. The mean age of subjects was 10.9 years. Of 434 children, 50.5% was boys; about half of them were the 5th grade students, and the rest half were the 6th grade students. 55.8% reside in Seoul and 44.2% live in Kyungki-do. There were not statistically significant differences in the distribution of grade or residence area by gender. Those who exercise three or more times per week were 59.2%, with higher percentages in boys than in girls (70.3% for boys, 47.9% for girls). Those who do not exercise or do rarely were 3.2% for boys and 7.9% for girls (p<0.001). The mean hours of TV watching was 1.8 hours per day, which was significantly higher in boys (2.0 hours/day) than in girls (1.7 hours/day, p<0.05).

Table 2 shows the utilization status of internet in the subjects. About 32% of subjects used the internet everyday, while 19.6% used it only when they needed. The distribution of internet use was different by gender; the percentages of using internet everyday was similar in boys and girls, but those who used it only when they needed were 14.2% for boys and 25.1% for girls (p<0.01). When they use the internet, they spent 1.3 hours each time on average; this was not significantly different by gender.

The main place for using internet was home (94.9%), both in boys and girls. The major purpose of using the internet was identified as 'to spend time or play game' (41.7%), 'to search data for homework' (33.8%), and 'to search information other than school work' (13.6%). The responses on this item were different by gender (p<0.001); for boys, 'spending time or playing game' was the major purpose of using internet (52.5% for boys vs. 31.0% for girls), while 'to search data for homework' was higher in girls (42.4%) than in boys (25.2%). Those whoever used health or nutrition websites were 23.3%, which was not significantly different by gender (Table 2).

Table 3 represents the results from the users of health or nutrition websites (n=101, 23.3%). About 69% used health or nutrition websites only when they needed. The common purpose of using these sites were 'to obtain health, nutrition information' (55%), 'to get information regarding weight control' (17%), and 'to do homework' (11%). By using nutrition websites, girls were more likely to get information regarding weight control than boys (21% vs. 11.6%), although this did not reach statistical significance. Fifty-six percent of users were very satisfied or satisfied with the nutrition websites they used, and 38% indicated the average satisfaction with the sites.

As to the problems of nutrition websites, the following was pointed out in the order of decreasing frequency; 'boring, uninteresting contents' (23%), 'difficult to understand the contents' (17%), 'lack of practical information' (17%), 'difficult to find the websites' (16%), and so on. With respect to the helpfulness of these sites, 30% and 58% of subjects responded that these were 'very helpful' and 'on average', respectively. 19.4% of users had experience of using nutrition counseling or Q&A sections in the websites. The distribution of satisfaction with the nutrition websites, problems of nutrition sites, helpfulness of these sites, and experience of using counseling or Q&A sections was not significantly different by gender. Seventy-six percent of users had intention to use these sites in the future; this intention was higher in girls (80.4%) than in boys (70.7%), although it did not reach statistical significance.

For non-users of health or nutrition websites (76.7%), reasons for not using were asked (Table 4). Major reasons were identified as 'obtain information through other media' (35.6%), 'not interested in health or nutrition' (33.8%), and 'do not know websites providing information regarding health or nutrition' (21.5%). For boys, these took 32.6%, 37.1%, 19.4% of responses respectively, and for girls, these explained 39.1%, 30.1%, and 23.7% of responses respectively. About 39% of non-users responded that they intend to use health or nutrition sites in the future, and this intention was significantly higher in girls (46.5%) than in boys (31.4%, p<0.01).

The preferred topics in developing nutrition websites for children are shown in Table 5. Interesting topics to the subjects included assessment of obesity (e.g., how to assess obesity, know my obesity index), exercise methods, proper weight control methods, special nutrition information (e.g., diet for stature growth, academic performance), dietary assessment (e.g., eating behavior, dietary intakes), and food hygiene/preventing foodborne diseases. Compared to boys, girls showed more interest in topics presented, and showed significant differences in topics such as assessment of obesity (p<0.001), special nutrition information, cooking snacks (p<0.01), proper weight control methods, childhood obesity, and link to other nutrition websites (p<0.05). In general, subjects were relatively not interested in items such as nutrition counseling and link to other nutrition sites.

As the useful methods in developing nutrition websites for children, the majority of subjects selected 'providing general information and game, quiz' (36.6%), 'providing general information and Flash animations' (31.4%, Table 6). When asked to choose the color among the response categories or to write the color for website screen, subjects responded that they liked green (24.3% of subjects), white (19.2%), blue (18.7%) and yellow (17.8%); Favorite colors were blue and green for boys, and green and white for girls (p<0.001). For text colors, black (47.0%) was the most favored color, followed by blue (17.0%) and green (16.7%). The preference for text colors were also different by gender (p<0.01). Subjects responded that nutrition websites be updated every month (39.2% of subjects) or every two weeks (35.6%).

Results regarding the preferred topics for school nutrition education are presented in Table 7. Similar to the topics for nutrition websites, assessment of obesity (e.g., how to define overweight or obesity, know my obesity index), exercise methods, special nutrition information (e.g., diet for stature growth, diet for academic performance), dietary assessment (e.g., assess my eating behavior, nutrient intakes), child obesity and adequate weight control were the topics that subjects expressed more interest in. In addition, subjects liked to know about cooking snacks or selecting snacks. In general, girls showed more interest in the topics presented. More specifically, girls compared to boys, were more interested in topics including assessment of obesity, childhood obesity and adequate weight control, cooking snacks (p<0.001), special nutrition information, selecting snacks, and dietary assessment (p<0.05).

About 17% of subjects responded that they had experience of nutrition counseling with dietitians at schools (Table 8). For the preferred nutrition education methods, 89.5% of subjects chose activities (e.g., cooking, exercise, games), which was high in girls (92.1%). As nutrition education materials, subjects liked materials using computers (moving pictures, CD) (37.5%), followed by video (25.2%), internet (16.2%) and booklets (13.9%). The preferred education methods or education materials were not significantly different between boys and girls. As the desired frequency of nutrition education, subjects responded that they wanted to receive nutrition education 5.7 times per semester on average; 6.1 times for boys and 5.4 times for girls. The mean of desired length for nutrition education was 42.6 minutes in a session.

This study examined the utilization status of the internet and health or nutrition websites, as well as the needs of children for developing nutrition websites and education programs among 5-6th grade students. Using the internet becomes a part of daily life, even in children. It appeared that subjects spent quite a time (1.3 hours each time) on searching and surfing the internet. The degree of internet use was similar to the previous study with children (Her & Lee, 2003a), but lower than that of adolescents (Kim et al., 2003). Children in this study used the internet mainly to spend time/play games or to get information for homework, indicating that the internet has become a tool for playing and for information sources in this age group.

Compared to the widespread use of the internet among children, it seemed that using health or nutrition websites was not common in this study. Percentages of nutrition website users (23.3%) were similar to that in Her and Lee's study (28%, 2003a) but lower than that in the Hyun et al.'s study (52%, 2003). Major reasons for using nutrition websites (to get information related to health/nutrition and weight control) were somewhat different from the previous studies (to do homework) with children or adolescents (Hyun et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2002a). As problems of nutrition sites, the most frequent response was 'difficult to understand the contents' in boys and 'boring, uninteresting contents' in girls. Based on these findings, nutrition websites should be planned and developed considering interest and understanding levels of children, as well as providing practical information that fits to the children's routines. In addition, nutrition websites should also be technically constructed so that children could search and surf in the sites easily. Consistently, Her and Lee (2003a) pointed out that little interest, difficult contents, and poor information are the major problems of dietary information sites for children.

Three-quarters of subjects have never used the health or nutrition websites in this study. The main reasons for not using websites were 'getting information from other sources', 'not interested in health or nutrition', and 'do not know websites providing information regarding health/ nutrition'. From these, it is necessary to publicize well-developed nutrition websites to children, parents and teachers, as well as developing nutrition websites for children. In addition, it is needed to help children pay more attention to one's health, nutrition information and related-behaviors. Three-quarters of nutrition website users and 39% of non-users showed the intention to use the nutrition websites in the future, suggesting that websites could be the adequate avenues for providing nutrition information and inducing behavioral changes for children. It is also needed to manage and update the sites continuously after developing them.

The preferred topics for nutrition websites were similar to those for nutrition education at schools. These included assessment of obesity, exercise methods, proper weight control methods, and information regarding diet for growth or for academic performance. Girls compared to boys, showed more interest in nutrition topics and were concerned about weight issues. In school nutrition education, subjects indicated that dietary assessment, cooking or selecting snacks are the favorite topics in addition to the topics mentioned above. It might be said that children liked topics that they can participate in during education sessions or while using nutrition websites. Study findings suggest that nutrition websites or education programs for children include sections regarding specific nutrition information reflecting their needs, sections for self-assessment (obesity or eating behavior), as well as providing general nutrition information. Similar to the present study, Her and Lee (2003a) reported that the most interesting nutrition information among the 4-6th grade students were growth in stature, diets for academic performance, adequate weight control, and cooking. A study with elementary school dietitians (Ahn et al., 2007) also showed similar results with the current study as the preferred topics for nutrition websites of children.

The current study showed that nutrition websites for children also include sections such as games, quizzes and Flash animations as well as general nutrition information. From this, it is clear that nutrition websites or education programs might be more effective by incorporating sections that induce the interest and appeals to children. Previous studies also revealed that children expressed interest in sections using games, quizzes, animations, and cooking in nutrition education using websites (Her & Lee 2003a; Her & Lee, 2003b; Kim & Hyun, 2006). In contrast, middle school or high school students liked to have game, moving pictures and Q&A sections in nutrition sites for adolescents (Kim et al., 2003).

To be attractive to the children, screen or text colors needs to be considered. Color preference was apparently different between genders, as in Her and Lee's study (2003a). As for the desirable site update periods, the majority of subjects (75%) in the present study chose every month or every two weeks. It is not practical and is difficult to renew or update the nutrition websites in a short period of time, however, sections such as selecting and cooking snacks and nutrition boards might be updated periodically by having new information and recipes with seasonal foods.

Besides developing nutrition websites for children, it is expected that nutrition education at schools or fields be increasingly implemented. However, only 16.6% of subjects in this study had experience of nutrition counseling with dietitians at schools, suggesting the needs and opportunity for nutrition counseling or education be expanded in this sample. Assessing the needs of children for school nutrition education might provide the baseline data for systematically developing education programs. As stated before, favorite topics for school nutrition education were not basically different from those for nutrition websites. As the education methods, most of the subjects liked to have activities including cooking, games and exercise. Lee et al. (2005a) suggested having cooking practice, songs, nutrition games and role playing as methods for nutrition education, and Lee (2003) also stressed the importance of incorporating activity-based learning (e.g., games, songs and story-based activities). Recently, Woo et al. (2006) reported that activity-based nutrition education was effective in changing food behaviors as well as increasing nutrition knowledge. Thus, the nutrition education might be constructed to induce participation of children as well as providing nutrition information.

Results regarding education materials indicated that children preferred computers or the internet to printed materials. Similar to this, the previous study (Lee et al., 2005b) revealed that children were interested in the internet or games in nutrition education, however, printed materials, boards and written messages to home were commonly used in nutrition education due to resource constraints (Yoon & Lee, 2001). Previous study with elementary school dietitians (Ahn et al., 2007) also revealed that dietitians wanted education materials such as CD or internet than booklets or leaflets. These results suggest that computer technologies (CD, nutrition websites) might be diversely used to design and develop nutrition education materials for children. Computer-assisted instruction or education could be an effective means for changing nutrition knowledge or behavior of children, as suggested in some studies (Kim & Hyun, 2006; Matheson & Achterberg, 2001).

Subjects in this study wanted to receive nutrition education 5.7 times per semester. Time for each nutrition education (42.6 minutes) was close to class hours for elementary school children, indicating that each session should consider the attention spans of children. Shin et al. (2006) reported that about 70% of 3-6th grade students wanted to get nutrition education at least once a month. Nutrition education should be implemented systematically and continuously to get the observable effect. Currently, it might be difficult to provide nutrition education during regular classes; instead, discretional activities or extracurricular activities might be the opportunity for nutrition education at schools.

Some limitations in interpreting study results should be noted. Study results were based on a convenience sample of elementary school children, who were recruited from two elementary schools in Seoul and Kyungki-do. Thus, the findings might not be generalized to other groups of children (e.g., younger children, those in other geographic areas). This study was done using a questionnaire, which mostly consisted of closed questions based on literatures; therefore, there were limitations in getting in-depth information regarding the needs of children. Future study might be planned using qualitative methodology (e.g., focus group interviews or in-depth interviews with children) to investigate further what children want in nutrition websites or education programs. Future study might be done with parents of the children, perhaps because parents' point of view regarding nutrition and health might be different from that of children.

Despite these limitations, this study showed that the internet could be the useful route for children to provide nutrition information and educational messages. In addition, this study suggests what kinds of topics or methods might be effectively applied, in designing and planning nutrition websites or planning education programs. For example, nutrition websites for 5-6th grade children might include submenus for weight control, assessment of obesity or eating behaviors, special topics (e.g., diets for growth, academic performance), cooking or selecting snacks, as well as general nutrition. These submenus should be developed considering the understanding levels of children, and provide practical information that fit the children's routines. Based on the finding that girls were more concerned about weight control issues and nutrition, websites might have sections addressing adequate weight control especially for girls. Although it is practically difficult to update websites regularly, submenus such as selecting and cooking snacks, nutrition boards might be periodically revised by posting recent issues and recipes with easily prepared foods or seasonal foods. In developing nutrition websites, sections that are attractive to children, such as games, quizzes and Flash animations should be considered. Through these sections, nutrition messages can be more interestingly and effectively delivered to children. Moreover, games or quizzes could be used to reinforce the messages presented in the websites or education programs. Nutrition websites for children should be constructed in a way that children find the sites easily and search the contents with interest. It is also important to publicize nutrition websites for children as well as for school nutrition teachers or parents. Through these approaches, nutrition websites might be effectively used as educational tools in nutrition education at schools as well as at home.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Ahn Y, Kim HM, Seo JS, Yoon EY, Bae HJ, Kim KW. Needs assessment for developing a nutrition information site for elementary school children among elementary school dietitians. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition. 2007. 12:405–416.

2. Chung SJ, Lee YN, Kwon SJ. Factors associated with breakfast skipping in elementary school children in Korea. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition. 2004. 9:3–11.

3. Department of Health and Welfare & Korea Health Industry Development Institute. The Third Korea National Health & Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES III), 2005 - Nutrition survey (I). 2006. Seoul. Republic of Korea: Department of Health and Welfare.

4. Her ES, Lee KH. Development of computer-aided nutritional education program for the school children. Korean Journal of Nutrition. 2002. 35:791–799.

5. Her ES, Lee KH. Utilization status of internet and dietary information of school children in Gyeongnam and Jeonbuk areas. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition. 2003a. 8:15–25.

6. Her ES, Lee KH. Effect-evaluation of nutritional education program using internet for school children. Korean Journal of Nutrition. 2003b. 36:500–507.

7. Hyun TS, Yon MY, Kim SH, Kim NH, An SM, Lee SM, Chi HJ, Sun MH, Oh CH, Wang SH, Hong MK. Development of a nutrition education website for children. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition. 2003. 8:259–269.

8. Kang SA, Lee JW, Kim KE, Koo JO, Park DY. A study of the frequency of food purchase for snacking and its related ecological factors on elementary school children. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition. 2004. 9:453–463.

9. Kim GM, Lee YH. A study on nutrition management of dietitian for school lunch program in Seoul and Incheon provinces. Journal of the Korean Dietetic Association. 2003. 9:57–70.

10. Kim HY, Yang IS, Lee HY, Kang YH. The analysis of internet usage for nutritional information by junior and high school students in Seoul. Korean Journal of Nutrition. 2003. 36:960–965.

11. Kim SH, Hyun TS. Evaluation of a nutrition education website for children. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition. 2006. 11:218–228.

12. Kim YJ, Yoon EY. Development and evaluation of nutrition education program through internet. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition. 1999. 4:546–553.

13. Lee JW, Seo JS, Kim KE, Ly SY. A needs assessment to develop website contents on nutritional information and counseling for Teenagers. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition. 2002a. 7:664–674.

14. Lee KA. Activity-based nutrition education for elementary school students. Korean Journal of Nutrition. 2003. 36:405–417.

15. Lee KH, Her ES, Woo TJ. Development of nutrition education textbook and teaching manual in elementary school. Journal of the Korean Dietetic Association. 2005a. 11:205–215.

16. Lee KH, Kang HJ, Her ES. Adolescent internet utilization status of dietary information in Kyungnam. Korean Journal of Nutrition. 2002b. 35:115–123.

17. Lee YM, Lee MJ, Kim SY. Effects of nutrition education through discretional activities in elementary school - Focused on improving nutrition knowledge and dietary habits in 4th-, 5th- and 6th-grade students-. Journal of the Korean Dietetic Association. 2005b. 11:331–340.

18. Matheson D, Achterberg C. Ecologic study of children's use of a computer nutrition education program. J Nutr Educ. 2001. 33:2–9.

19. National Internet Development Agency of Korea, Ministry of Information Communication Republic of Korea. 2006 Survey on the computer and internet usage. 2007. Accessed on 8/1/07. http://isis.nida.or.kr/index_unssl.jsp.

20. Park YH, Kim HH, Shin KH, Shin EK, Bae IS, Lee YK. A survey on practice of nutrition education and perception for implementing nutrition education by nutrition teacher in elementary schools. Korean Journal of Nutrition. 2006. 39:403–416.

21. Pérez-Escamilla R, Haldeman L, Gray S. Assessment of nutrition education needs in an urban school district in Connecticut: establishing priorities through research. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002. 102:559–562.

22. Shin EK, Shin KH, Kim HH, Park YH, Bae IS, Lee YK. A survey on the needs educators, learners and parents for implementing nutrition education by nutrition teachers in elementary schools. Journal of the Korean Dietetic Association. 2006. 12:89–101.

23. Sung CJ, Sung MK, Choi MK, Kim MH, Seo YL, Park ES, Baik JJ, Seo JS, Mo SM. Comparison of the food and nutrition ecology of elementary school children by regions. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition. 2003. 8:642–651.

24. Woo TJ, Her ES, Lee KH. Effect-evaluation of nutrition education textbook and teaching manual in elementary school. Journal of the Korean Dietetic Association. 2006. 12:299–306.

25. Yoon HS, Lee KH. Study on foodservice and nutrition management for elementary schools in Kyungnam and Ulsan -Nutrition management-. Journal of the Korean Dietetic Association. 2001. 7:237–247.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download