Abstract

This study analyzed Kimchi eating culture in 178 households with female middle school children located in Incheon and Seosan areas, investigated the Kimchi eating patterns of female middle school students, and also analyzed the differences in value recognition for Kimchi between mothers and their female middle school students. Results showed that 23.0% of subject households answered eat Kimchi at every meal and the main reason for eating Kimchi in most households was good for taste. Most households made their own Kimchi, and only 12.3% of households bought Kimchi. Subject households preferred hot and spicy taste (34.8%) and pleasing taste (20.2%), and 44.4% of middle school children answered as eating Kimchi at every meal, and the source for information on Kimchi was home in 51.6% and mass media in 33.7%, suggesting the lack of school education. Both mothers and their female middle school students placed high value on Kimchi for its nutritional aspect and on Kimchi from the market for its convenience. Mothers showed significantly higher value (p<0.05) on the storage aspect of Kimchi compared to their middle school students, and female middle school students showed significantly higher value (p<0.05) on the value recognition for Kimchi as an international food compared to their mothers. Also, the value for hot pepper powder was high among other additional ingredients, and both mothers and middle school students had high values for Kimchi stew among other food dishes using Kimchi, and middle school students showed higher values (p<0.001) on foreign dishes using Kimchi such as Kimchi pizza and Kimchi spaghetti compared to the mothers group. Therefore, based on these results, the development of educational programs on Kimchi is needed not only at home but also at schools, by re-emphasizing the importance of value recognition for KImchi in our food culture.

Food culture is unique to any country or any race which had begun with their culture and developed while being influenced by surrounding environments, that is, geographical and historical circumstances, and thus a unique dietary tradition has been established during the developmental process.

Kimchi is the center of eating habits of Koreans and a representative Korean food which uses several vegetables as ingredients and is aged through fermentation (Kim & Yoon, 2002; Lee et al., 1998). As the nutritional excellence of Kimchi has been reported recently, the interest in Kimchi has increased internationally and is widely known world-wide as a representative food of Korea. The interest in Kimchi for its scientific aspects has increased. Kimchi is used as a source of vitamins, minerals and dietary fiber. There are important roles in nutritional supply and health maintenance of Koreans such as the prevention of constipation, hyperlipidemia, lowering serum cholesterol, inhibition of oxidative modification of LDL, inhibition of thrombus, prevention of lipid peroxidation and also an antiaging effect (Kim & Lee, 2001).

Despite these advantages, the preparation and cooking of Kimchi have gradually reduced recently because of several social changes. Also, it has been reported that the changes in eating habits have relatively lowered our recognition and preference for Kimchi, our unique traditional food, which has raised some concerns (Kim & Yoon, 2002). The process of making Kimchi is complicated and takes a longer time than making other foods and is also difficult to make an even taste, and thus the need for commercially-made Kimchi has increased recently. The consumption of commercially-made Kimchi, compared to the annual total Kimchi demand, has increased 27.7% in 1997, 28.8% in 1998, 30.1% in 1999, and 31.3% in 2000 with ever increasing tendency annually (Kim & Lee, 2001).

Eating habits are most established before the adolescence and is greatly affected by dishes eaten at home during childhood and by experiences with foods during adolescence, which then contributes to food selection thereafter (Stasch et al., 1970). The recognition of foods established during this period can influence not only the future of individuals but also their future family members (Howe & Vaden, 1980). According to a study on Kimchi eating habits during the growing period (Song et al., 1995), reasons for eating Kimchi were good for health and our traditional food, showing positive recognition for eating Kimchi. It was also reported that Kimchi intake had increased from the recommendation for eating Kimchi from parents was stronger or grandparents living in the same household. Kimchi can have various tastes depending on the person making Kimchi, or weather, but the taste is greatly affected depending on the selection of good quality ingredients, mixing of the ingredients, methods and storage conditions. Song et al. (1995) reported that children liked Korean cabbage Kimchi most and disliked ingredients with strong flavor such as ginger, garlic, green onion, and salted fish, and thus it would be desirable to use Korean cabbage for making Kimchi rather than radish and to use less ingredients with strong flavors. Also, the type of Kimchi children wanted was somewhat sweet, less spicy, no strong flavor, well fermented Kimchi with fruits such as pears, apples, or mandarin oranges, and small pieces in size. In case of middle school students, it was reported that reasons for liking Kimchi were due to hot and spicy taste, crunching sensation, and sourish taste (Kim & Yoon, 2002). The preference for Kimchi in the aspect of degree of fermentation was well-fermented Kimchi (57.0%) (Song et al., 1995). The reason for preferring Korean cabbage Kimchi and cubed radish Kimchi could be interpreted as adaptation in taste due to the fact that most households prepared Kimchi using Korean cabbage and radish. If this phenomenon is true, children should be provided with opportunities for experiencing various types of traditional Kimchi as early as possible, not only to increase Kimchi consumption, but also to inherit the traditional culture for Kimchi. Also, it is considered that various types of Kimchi should be on the market and supplied in meal services because the ratio of home-made Kimchi has already decreased and that of commercially-made Kimchi in the market has increased.

It is necessary to make children have positive values for Kimchi from childhood, to show the process of making it at home, and to practice nutritional education and guidance for proper recognition while parents are eating meals with children. Studies on Kimchi so far have been interested in the ingredients (Cho, 1988; Yoon & Rhee, 1997), physical characteristics (Lee, 1988), storage & additional ingredients (Lee et al.,1998; Lee, 1988) and more, but studies on the recognition are very few. In addition, almost no comparative study on the recognition for Kimchi between mothers and their female middle school children in the same households was searched.

Thus, this study was performed to analyze the Kimchi eating patterns in subject households and to investigate the Kimchi eating patterns of female middle school children in subject households. Also, through comparative analysis for Kimchi between mothers and their children, the differences between generations in the recognition for Kimchi and eating patterns were investigated.

The research questions of this study were as follows:

First, what are Kimchi eating patterns in subject households?

Second, what are the recognition and eating patterns of Kimchi in middle school children?

Third, what is the difference in value recognition for Kimchi between mothers and middle school children?

This study was performed for 200 households with female middle school students, by selecting 100 households each in the Incheon and Seosan areas, to investigate the value recognition for Kimchi and the Kimchi eating patterns. The questionnaire was developed to each female middle school student and her mother in the same household. The survey was performed for 13 days from April 18 to April 30, 2005. The questionnaires were distributed to 200 households were collected from 178 households.

The questionnaire of this study was reconstructed for the purposes of the study based on the survey tool presented in the previous study (Kang & Han, 2002) and then modified and complemented through a preliminary study (n=50), to analyze the recognition for Kimchi and eating patterns in female middle school students and their mothers.

The contents of the survey included Kimchi eating patterns in subject households, Kimchi eating patterns of middle school children, and the differences in the recognition for Kimchi between mothers and their middle school children.

(1) For Kimchi eating patterns in subject households, the degree of Kimchi intake in subject households, reasons for eating Kimchi, and sources for Kimchi supply were investigated. Also, the degree of preference for Kimchi in subject households was investigated for the areas of type, taste, and degree of fermentation.

(2) Kimchi eating patterns of middle school children were analyzed. For the degree of recognition for Kimchi, and how to make Kimchi, sources for information on Kimchi, and the number of types of Kimchi recognized by middle school students were investigated. Also for the analysis of Kimchi eating patterns, the number of Kimchi intakes per day, Kimchi intake per meal, and major types of Kimchi intake were investigated.

(3) For the analysis of differences in values for Kimchi between mothers and their middle school children, each of 4 questions were asked for nutritional aspects, cooking aspects, economical aspects, preference aspects, and cultural aspects, respectively. Also, the degree of values following the addition of ingredients and seasonings and the degree of values for dishes using Kimchi were analyzed. The scores for the degree of recognition for Kimchi as food value were 1 point for strongly disagree, 2 points for disagree, 3 points for so-so, 4 points for agree, and 5 points for strongly agree, and the scores for the degree of preference for ingredients and seasonings and for dishes using Kimchi were I point for strongly dislike, 2 points for dislike, 3 points for so-so, 4 points for like, and 5 points for strongly like.

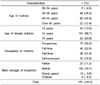

General characteristics of subjects were presented in Table 1. The age distribution of mothers in subject households showed 80 (44.9%) for 40~45 years, the highest ratio, and 68 (38.2%) for 35~40 years, and 22 (12.4%) for over 45 years. The age distribution of middle school children showed 101 (56.7%) for 14 years, the highest ratio, and 53 (29.8%) for 15 years, and 24 (13.5%) for 13 years. The occupation of mothers in subject households was in the order of housewife (39.3%), full-time job (22.5%), and self-employed (16.8%). The meal manager of household was mother (78.7%) and father (11.2%).

The degrees of recognition for Kimchi in subject households were investigated. As presented in Table 2, 41 households (23.0%) answered as eating Kimchi at every meal and 117 households (65.7%) answered as eating Kimchi at every meal if possible. Also, 11.3% of total subjects answered as not eating much. The results of reasons for eating Kimchi showed preference (good taste) (53.4%), general eating (19.6%), good for health (14.6%), and tradition (4.5%). The home-made Kimchi (45.5%) was the main source of supply and 12.3% of total subjects got commercially-made kimchi. The ratio of consumption of commercially-made Kimchi from the market was considerably high in this study.

The taste of Kimchi preferred by subject households was presented in the order of hot and spicy taste (34.8%) and refreshing taste (26.4%). In addition, pleasing taste was answered in 36 households (20.2%) and sourish taste was answered in 25 households (14.1%). We know that the preference taste of Kimchi is hot and spicy in this study Table 3.

The degree of recognition for Kimchi in female middle school students was presented in Table 4. Female middle school students answered for the knowledge on how to make Kimchi as little acknowledged in 122 students (68.5%) and well acknowledged in 22 students (12.4%). The channels of information on Kimchi answered by female middle school students were home in 92 students (51.6%) and mass media in 60 students (33.7%). In addition, school was answered only in 8 students (4.5%). The numbers of kinds of Kimchi that female middle school students knew was 4-6 in 70 students (39.3%) and 6-8 in 52 students (29.2%). This result showed that there was little role in education for Kimchi at school.

Kimchi eating patterns of female middle school students were shown in Table 5. For the number of Kimchi intakes per day, eat at every meal per day was answered in 79 students (44.4%), eat at two meals per day in 58 students (32.6%), and eat at one meal per day in 36 students (20.2%). The amount of Kimchi intake per meal was more than 5 pieces in 98 students (55.1%), 3~4 pieces in 57 students (32.0%), and 1~2 pieces in 18 students (10.1%). The kind of Kimchi most frequently taken was Korean cabbage Kimchi in 86.0% of total subjects.

The value recognition for Kimchi was analyzed in mothers and their female middle school students of same subject households. The value recognition for Kimchi was evaluated in 5 aspects for food scientific values of Kimchi, and also analyzed in the aspects of value recognition after the addition of ingredients and seasonings and for dishes using Kimchi.

The recognition of food scientific values of Kimchi was asked in 5 aspects including nutritional and health aspects, preferential aspects, cooking and storage aspects, economical aspects, and cultural aspects, with 4 questions for each aspect, and also comparative questions for Kimchi on the market were added for each aspect.

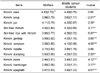

The results in the nutritional and health aspect, as presented in Table 6, were analyzed that both mothers (4.52) and female middle school students (4.50) showed higher agreement on the value for nutrition and health aspects of Kimchi. Thus in the aspects of Kimchi is nutritious and Kimchi is helpful in the prevention of diseases, both mothers and students showed higher agreements of over 4 points, without significant differences among groups. However, the recognition of Kimchi as a dieting food showed significantly higher agreement (p<0.001) in the mothers group (3.86) than in the students group (3.53). On the other hand, the question that Kimchi from the market was more nutritious than homemade Kimchi showed no difference between mothers (2.27) and students (2.23), showing overall low agreement.

The statistical results in the cooking and storage aspect showed that mothers (4.51) had significantly higher agreement (p<0.05) to the value of Kimchi has good storage than students (4.27). For the value Kimchi should be made at home, both mothers (4.35) and students (4.27) showed higher agreement. On the other hand, for the value various kinds of Kimchi are available, both groups showed lower agreements. For the value Kimchi on the market is convenient', mothers (3.57) showed significantly higher agreement (p<0.001) than students.

The statistical results in the economical aspect of Kimchi showed that mothers (4.04) had significantly higher agreement (p<0.05) than their students (3.70) for the item homemade Kimchi costs less. In addition, for items such as making Kimchi takes long time, one type of Kimchi is good enough for side dishes, and Kimchi on the market is more economical, both groups showed lower agreements.

The statistical results in the preferential aspect of Kimchi showed that both mothers (4.40) and students (4.29) had higher agreements for the item Kimchi is tasty, and mothers (2.17) had significantly higher agreement (p<0.001) than students (1.80) for the value item Kimchi is too hot (spicy). Also, for the item Kimchi has a unique flavor, mothers (2.50) showed significantly higher agreement (p<0.001) than students (1.99). On the other hand, for the item Kimchi from the market is more delicious, both groups showed lower agreements.

Both groups showed relatively higher agreements for the aspect that Kimchi is an everyday food that people always eat, and mothers (3.82) showed significantly higher agreements (p<0.001) than students (3.33) for the item Kimchi gets along well with other foreign foods. For the item Kimchi is an international food, students (4.09) showed significantly higher agreement (p<0.05) than mothers (3.73).

The degree of values for additional ingredients used in Kimchi was shown in Table 7. The results for the difference of values in mothers and their children depending on additional ingredients and seasonings were analyzed, in which items with the agreement of over 3 points were in the order of green onion (4.08), leek (3.99), leaf mustard (3.74), oyster (3.61), carrot (3.31), and perilla leaf (3.30) in mothers, and perilla leaf (3.32) and leek (3.16) in middle school students. It suggested a relatively higher preference for additional ingredients in mothers than in students. In the preference for seasonings, with the average of over 3 points, middle school students showed in the order of hot pepper powder (3.38) and sugar (3.12), and mothers showed in the order of hot pepper powder (4.22), garlic (4.08), salted fish (3.90), ginger (3.75), and sugar (3.25). Also, the degree of preference for seasonings was generally higher in mothers than in students, and both groups showed the highest preference for hot pepper powder among the seasonings.

Agreements in the values for dishes using Kimchi were analyzed as presented in Table 8. The degree of agreements for Korean dishes using Kimchi was high for Kimchi stew in both mothers and middle school students groups. Also, mothers group showed significantly higher degree of agreement for Kimchi stew among dishes using Kimchi than the students group. In addition, middle school students showed significantly higher agreement for items such as Kimchi soup, Kimchi pancake, stir-fried Kimchi. Kimchi ramyeon, and Kimchi dumpling compared to mothers. Also, foreign foods using Kimchi such as Kimchi pizza (p<0.001), Kimchi hamburger (p<0.05), and Kimchi spaghetti (p<0.001) all showed significantly higher agreement in middle school students than in mothers.

This study analyzed Kimchi eating patterns in 178 households with female middle school students located in Incheon and Seosan areas and investigated differences in value recognition for Kimchi between mothers and their middle school students.

The frequency of eating Kimchi in subject households showed that 23.0% of households answered as eating Kimchi at every meal and 65.7% answered as eating Kimchi at every meal if possible, and the main reason for eating Kimchi was mostly because of good taste. Most households answered as making Kimchi at home by themselves, but the ratio of consumption of commercially-made Kimchi from the market was considerably high. Respondents preferred the taste in the order of hot and spicy taste (19.1%), and refreshing taste (14.5%). They preferred Korean cabbage Kimchi (33.6%). According to the study by Han et al. (1998), 82.0% of high school students answered as eating Kimchi for sure or if possible, in which the recognition for Kimchi eating was similar to the tendency of this study, and 15.6% of students answered as not eating if possible, which was higher than similar response (7.9%) in this study. Some researches (Kim & Yoon, 2002; Kim et al., 2001) reported in the study on the recognition and preference for Kimchi among traditional Korean foods that, for the question whether Kimchi should be eaten at each meal, middle school students answered as should eat at each meal (35.8%) and may not eat (41.6%), and respondents in their 30s answered as should eat at each meal (48.5%) and may not eat (45.5%), and respondents over 40s answered as should eat at each meal (63.3%) and may not eat (30.6%), suggesting the difference in recognition between generations as shown in this study. In case of middle school students, it was reported that reasons for liking Kimchi were due to hot and spicy taste, crunching sensation, and sourish taste and the preference for the degree of hot (spicy) taste was in the order of hot taste (79.4%), not-so-hot taste (13.9%), and very hot taste (8.9%) in middle school students in Masan and Changweon areas (Kim & Yoon, 2002). These results are similar to ours. Changes in eating habits have brought the changes in the production and consumption of Kimchi. The conventional home-made Kimchi has been changed to commercialized and industrialized Kimchi, and the consumption of Kimchi has gradually decreased. Song et al. (1995) reported in the study on Kimchi consumption in the Busan area that 83.0% of elementary students thought they should eat Kimchi but only 68% answered that they actually liked Kimchi, and 14.0% of students answered that they disliked Kimchi. The intake per meal was reported as more than 5 pieces per meal in 26.5% of students and less than 1~2 pieces or none in 64.7% of students answered, showing the difference between the recognition for Kimchi eating and actual intake. In this result, the Kimchi intake per meal was more than 5 pieces' in 55.1% of total female middle school students. It is a higher intake than elementary school students by previous research (Song et al., 1995). Kim et al. (2002) reported 59.7% of middle school students in Masan and Changweon areas, and Park et al. (2000) reported 74.4% of female high school students, as the percentages of respondents who liked Kimchi.

The results of this study showed that female middle school students answered for the knowledge on how to make Kimchi as little acknowledged in 122 students (68.5%) and well acknowledged in 22 students (12.4%). The channels for information on Kimchi answered by middle school students were home (51.6%) and mass media (33.7%) and school (4.5%). According to previous studies, it was reported that female students thought Kimchi making as difficult task with higher agreement for the item making Kimchi is difficult (Lee et al., 1999). But 88.7% of respondents helped their mothers when making Kimchi, suggesting that making Kimchi at home can be considerably handed down to some extent. However, the desirable place for learning how to make Kimchi was answered most as from mother (88.0%) and only 3.0% of students answered as school, which was even less than 4.1% for self-learning.

For the recognition for Kimchi, both middle school students (4.50) and mothers (4.52) showed high degree of agreements for the item Kimchi is excellent in nutritional aspect. In the previous studies (Kii, 1997; Han et al.,1997), very high agreement for the item Kimchi is nutritious among general recognitions for Kimchi was reported, which showed similar a tendency as the results of this study. For the preferential aspect, both middle school students (4.29) and mothers (4.40) showed the highest degree of agreements for the item Kimchi is tasty. For the economical aspect, both middle school students (3.70) and mothers (4.14) showed the highest degree of agreements for the item homemade Kimchi costs less. Also for the cultural aspect, middle school students (4.09) placed more value on Kimchi is an international food compared to mothers (3.73). In the study with elementary school students (Song et al., 1995), for the reasons of eating Kimchi, 48% answered as good for health and 31.8% answered as our traditional food, showing positive recognition on Kimchi intake, and the preference for Kimchi in students seemed higher as the recommendation for Kimchi intake from parents was stronger. Also, it was reported that there was no significant differences in the preference for Kimchi depending on school grades, gender or family circumstances, but the presence of grandparents in the household was the most influential factor among others. Kim et al. (2002) pointed out that the value for Kimchi and the degree of preferences for various types of Kimchi and Kimchi-using foods were higher in middle school students as they had more knowledge on Kimchi and thus systematic education on Kimchi is needed at school and should be reflected in the classroom and nutrition education by school dietitians should be actively developed to promote the recognition for our traditional foods.

The statistical results in the recognition for commercially-made Kimchi in the market showed that respondents agreed on the fact that it was convenient. As the use of commercially-made Kimchi on the market has increased and the ratio of home-made Kimchi has gradually decreased, it is difficult to expect students to learn how to make Kimchi at home. There are some changes in the recognition for commercially-made Kimchi in the market depending on the time. A study in 1997 (Yoon et al., 1997) reported that the most suggested improvement in commercially-made Kimchi in the market was thought as hygienic aspect (80.8%), but a study in 1995 (Song & Han, 1999) reported that it was to maintain even taste and degree of fermentation (45.8%). In the study with female college students in the Busan area (Kim & Kim, 1998), the reason for not making Kimchi after marriage was not self-confident in making delicious Kimchi in 55.8% of the respondents, suggesting that the education for making Kimchi should be certainly needed at school. In particular, it is considered that education on the proper value for Kimchi and on how to make Kimchi in female students can prepare the foundation for fast and effective development of our traditional food, Kimchi.

The analysis for values by additional ingredients and seasonings showed that a generally higher preference for additional ingredients in mothers compared to their students. For the seasonings, both mothers and middle school students groups showed the highest agreements for hot pepper powder. The values for food dishes using Kimchi showed high agreement for Kimchi stew, and fusion foods using Kimchi (Kimchi pizza and Kimchi spaghetti) had higher values in middle school students. Thus, Korean food using Kimchi had higher preference than fusion foods using Kimchi, suggesting that foods with higher intake experience showed higher degree of preference and foods with lower intake experience showed lower degree of preference.

The following suggestions were made from the above results:

First, educational programs are needed not only at home but also at school to improve the recognition for Kimchi and eating patterns in female middles school students.

Second, the opportunity for eating Kimchi should be increased through the development of various foods using Kimchi.

Third, the contents on Kimchi among the curriculum of technology/home economics in the school education should be reviewed and emphasized by presenting basic data and thus students can acquire more scientific and better information and knowledge of Kimchi, a leading item of our food culture, through the development of educational programs and further establish desirable Kimchi eating patterns.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Cho Y. A Study on flavorous taste components in Kimchis on free amino acids. The Korean Journal of Culinary Research. 1988. 3:107–109.

2. Han JS, Joe YS. A Survey of high school students' awareness of and uses for Kimchi in Taegu area. Journal of the Korean Home Economics Association. 1998. 36:127–137.

3. Howe SM, Vaden AG. Factors differentiating participants and nonparticipants of the National School Lunch Program. J Am Diet Assoc. 1980. 78:451–457.

4. Kang SY, Han MJ. Consumption pattern of Kimchi in Seoul area. Korean Journal of Food and Cookery Science. 2002. 18:684–691.

5. Kim DM, Lee JH. Current status Korean Kimchi industry and R&D Trends. Food industry and Nutrition. 2001. 6:52–59.

6. Kim EH, Kim SR. A survey on the notion and intake of Kimchi among college Women. The Korean Journal of Food and Nutrition. 1998. 11:513–520.

7. Kim JA, Yoon HS. A survey on middle school students preferences for Kimchi in Masan and Changwon city. Journal of the Korean Dietetic Association. 2002. 8:289–300.

8. Kim JH, Park WP, Kim JS, Park JH, Ryu JD, Lee HK, Song YO. A survey on the actual state in Kimchi in Kyung-Nam (1)-The study of the preference of Kimchi and actual amounts of Kimchi intake. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Culture. 2000. 15:52–58.

9. Kim SY. Survey of American university students perception and preference for Kimchi. 1999. Yongnam University;MS thesis.

10. Lee CH. Macro- and microstructure of Korean cabbage leaves and their texture measurements. Korean Journal of Food Science Technology. 1988. 20:742–748.

11. Lee JY, Cho Y, Hwang IK. Fermantative characteristics of Kimchi prepared by addition of different kinds of minor ingredients. The Journal of Korea Society of Food and Cookery Science. 1998. 14:1–8.

12. Lee KH, Park ES. Intake and evaluation of commercial Kimchi and perception of learning methods making Kimchi among female high school students. The Korean Society of Human Ecology. 1999. 2:89–98.

13. Moon HJ, Lee YM. A survey on elementary, middle and high school student' attitude and eating patterns about Kimchi in Seoul and Kyunggido area. Korean Journal of Dietary Culture. 1999. 14:29–42.

14. Kii NS. Housewives' consumption aspects of Korean fermented foods in Taejon. Journal of Korean Society Food Science Nutrition. 1997. 26:714–725.

15. Park DK, Lee C, Yoon SI, Ha SS, Lee YN. Changes in the textural properties of Kimchi during fermentation. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Culture. 1989. 4:167–172.

16. Park ES, Lee KH. The intake, preference, and utilization of Kimchi in female high school students. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition. 2000. 5:89–98.

17. Song JE. A survey on perception and purchase about marketed Kimchi of housewives in Daegu area. The Journal of the Korean Home Economics Association. 1995. 33:121–128.

18. Song JE, Kim MS, Han JS. Effects of the salting of chinese cabbage on taste and fermentation of Kimchi. The Journal of Korean Society of Food and Cookery Science. 1995. 11:262–232.

19. Song YO, Kim EH, Kim M, Moon JW. A survey on the children notion in Kimchi (1)-Children preference for Kimchi-. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition. 1995. 24:758–764.

20. Stasch AR, Johnson MM, Spangler GJ. Food practices and preferences of some college students. J Am Diet Assoc. 1970. 57:523–527.

21. Yoon JS, Rhee HS. A study on the volatile flavor components in Kimchis. Korean Journal of Food Science Technology. 1997. 9:116–122.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download