Introduction

Obesity has become one of the central public health concerns globally. The prevalence of obesity has been on the rise among children and adolescents both in developed and developing countries (Flegal, 1999 & 2000; Kromeyer-Hauschild et al., 1999; Moreno et al., 2000; Ogden et al., 2006; Reilly & Dorosty, 1999; WHO, 2006). National data also indicate alarming rates of obesity prevalence in children and adolescents, peaking at 29.3% for the age group of 10-14 years (KMHW & KCDC, 2006). This trend of early onset of obesity associated with several health conditions including cardiovascular diseases, some cancers, diabetes, high blood pressure, and dyslipidemia puts a high order of priority on obesity prevention efforts targeting children and adolescents.

Although obesity prevention can be explained by a very simple concept of energy balance, modification of individuals' behaviors toward adequate energy balance is a very challenging topic due to complex links of obesity with individual, environmental, and behavioral contexts. Understanding how these diverse factors differ between obese and non-obese adolescents has interested a few investigators looking for smart guidelines to stop the obese epidemic (Chen et al., 2005; Gordon-Larsen, 2001). Along with the objective body weight status, the role of adolescents' subjective body satisfaction status in explaining the obesity-related context has also been studied (Mikkilä et al., 2003). This latter approach seems just as interesting as the former one, based on several investigations reporting some discordance between objective and subjective body status variables among adolescents (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 1997; Nowak, 1996; Rinderknecht & Smith, 2002; Story et al., 1994).

This pattern of observed body dissatisfaction in all body weight groups has been reported to be also a characteristic of elementary school children (Hill et al., 1994; Rinderknecht & Smith, 2002). However, previous studies have paid little attention to the roles that objective and subjective body status variables play in multi-faceted aspects around obesity. The elementary school year is a critical period for obesity control throughout a lifetime and is a surging period of obesity prevalence (KCDC, 2006).

The objective of this study, therefore, was to examine various aspects related to obesity across levels of body weight and body shape satisfaction among elementary school children. Specifically, we looked at obesity-toward attitudes, obesity-related nutritional knowledge, and practice of healthy eating behaviors. The pursuit of the study questions was conducted by a gender-specific approach.

Subjects and Methods

Subject Recruitment and Data Collection

Study subjects were recruited from 2 public elementary schools located in the suburban areas of Seoul (Koyang and Ansan, Kyunggi-do). A total of 5 fifth grade classes were chosen for participation in this study. The survey questionnaires were self-administered in the presence of teachers in charge of the participating classes. The researcher, in advance, met with the teachers to explain several issues about the survey administration in an effort to collect quality data. The survey took about 20-30 minutes to complete, and school supplies or snacks were given as an incentive. Out of 279 surveys collected, 19 were excluded from the analysis for this study due to a high proportion of unanswered survey items (>20%).

Questionnaire Development

The survey questionnaire was developed to be self-administered. It included several domains of questions including demographics, physical activity, body size and satisfaction, obesity-toward attitudes, obesity-related knowledge, and practice of eating behavior guidelines.

Weekly frequency of regular leisure-time physical activity was asked with response options of none, 1-2 times, 3-4 times and 5 times and more. Information on self-reported height (cm), weight (kg), and the degree of body satisfaction was attained. A percent value of ideal body weight (PIBW) was calculated for each subject using data from the Korean Pediatric Association (2000) for a standard body weight for height. Those with PIBW values less than 90 were categorized into an underweight group, from 90 to 110 into a normal weight group, and greater than 110 into an overweight/obese group. For grouping according to subjective body satisfaction status, those answered very satisfied or satisfied on the question of 'how much are you satisfied with your body shape (image)?' were categorized into a satisfied group, dissatisfied or very dissatisfied into a dissatisfied group, and so-so into a neutral group.

Survey items to estimate the obesity-toward attitudes were drawn up based on the Attitudes Toward Obese Persons Scale by Allison et al. (1991). It comprised 10 questions each of which was 5-point Likert-typed. Major themes in the questions include perceptions of obese persons as displaying negative personality, experiencing social problems, having low self-esteem, and possessing physical inferiority. The total score of the attitudes were calculated by summing up the scores of 10 questions for each subject, and thus could range from 10 to 50 with a lower score representing more negative attitudes.

A total of 10 questions (yes/no type) on the obesity-related knowledge were derived from review and modification of the Obesity Knowledge Quiz (Price, 1985). The questions were designed to estimate knowledge on etiology of obesity, diseases related to obesity, and weight management skills. A point was given for a correct answer, making a score of 10 a full mark.

A series of questions was developed to measure the level of compliance with the eating behavior guidelines for children issued by the Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Korea Health Industry Development Institute in 2003. The guidelines include 14 specific guidelines under 7 main guidelines, and these specific guidelines provided the frame for the question development. The specific guideline addressing to be aware of adequate height and weight for an age was excluded from constructing the questionnaire since this guideline does not actually focus on behavior but on knowledge. With thirteen 5-choice Likert-type items, the total score of practicing the eating behavior guidelines could span from 13 to 65. A higher score represents a better practice of the eating behavior guidelines.

The Cronbach's alpha coefficients of internal consistency for various sections of the survey were examined and found to be reasonable. The coefficients were 0.80, 0.71, and 0.76 for the sections of the attitudes, knowledge, and eating behaviors, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated as a mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and a frequency and proportion for categorical variables. Chi-square test was employed to examine the effects of gender on subjective and objective body status variables. To test a null hypothesis of no difference in the attitudes, knowledge, and dietary practice among three PIBW groups and body satisfaction levels, one-way analysis of variance was used. These comparative analyses were done gender-specifically at the 0.05 significance level. All the descriptive and comparative analyses were conducted using a SAS program (SAS Version 9.1, Cary, NC, USA)

Results

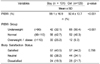

Table 1 presents general characteristics of a total of 260 participants (129 girls and 131 boys). Most had at least a working parent, rated their own health status as better than unhealthy, and had regular physical activity of more than once a week. The information suggests the study subjects are generally healthy children under ordinary parental care.

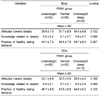

Means or distributions of subjective and objective body status variables are shown by gender in Table 2. Mean values of PIBW were within a normal range in both genders, but significantly higher in boys compared to girls (boys: 99.1 ± 16.9, girls: 92.4 ± 13.7, p < 0.001). Accordingly, proportions of underweight children and overweight/obese children in girls were greater and smaller, respectively. This difference of the distribution reached to statistical significance (p < 0.001). In spite of this gap in body weight status between boys and girls, data on a self-rated level of body shape satisfaction indicated no gender-difference. This disagreement between objective and subjective body status data seems to arise from the girls' rather negative perceptions of their body figure. That is, only 9.3% of the girls were objectively categorized as overweight/obese, but more than twice the number of girls reported dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with their body shape.

In consideration of this gender difference in the profile of subjective and objective body status variables, the next steps of the analyses were done gender-specifically. Mean scores of attitudes toward obesity, knowledge related to obesity, and practice of the eating behavior guidelines were compared among the three PIBW groups for both genders (Table 3). No statistically significant differences were detected in boys and girls.

Results from comparisons of mean scores of the attitudes, knowledge, and eating behaviors among subjective body satisfaction levels are presented in Table 4. There were no statistically significant differences in boys, either. However, girls who were dissatisfied with their body shape reported more negative attitudes toward obesity than the other groups (satisfied: 34.0 ± 6.5, dissatisfied: 29.0 ± 5.3, p=0.002). Mean scores of practice of healthy eating guidelines were, in addition, lower in the dissatisfied girls than in the satisfied girls (satisfied: 46.9 ± 6.5, dissatisfied: 42.4 ± 8.5, p=0.037). The knowledge score was not significantly dependent on the body satisfaction levels in girls.

Discussion

The present study compared the attitudes toward obesity, nutritional knowledge on obesity, and practice of the eating behavior guidelines between different levels of body weight and body shape satisfaction in 5th-grade boys and girls, adding to a rather scarce body of literature on the issue in this age group.

Our examination on distribution of objective body weight status and subjective body satisfaction status suggested a distinct gap between the two features among girls grounded on the girls' negative perceptions of their body figures. This result is consistent with others' previous findings. Hill et al. (1994) observed stronger discontent in body shape and desire for thinness among girls compared to boys in a cross-sectional study with 379 nine-year old children. Another larger cross-sectional examination of 868 third grade students reported an excess of overweight concerns which appeared to result in depressive symptoms in girls, but not in boys (Erickson et al., 2000). Kim et al. (2002) also found that more girls in a normal body weight range perceived themselves as overweight or obese than the boys did in a cross-sectional investigation among 2,590 children and adolescents in Jeju city. The consensus that girls are more likely to desire a thin body shape compared to boys by preadolescent period, hint that interventions to reduce obesity may need to reflect this early gender-difference. It also needs to be acknowledged that elementary school girls may be more dependent on their subjective body status in terms of several obesity-related issues.

This study observed scores of obesity-related knowledge and eating behaviors were not dependent on objective body weight status in either gender. Such lack of association between health, or nutritional knowledge, and body weight is not quite new information. Nutrition educators have long been aware of it from repetitive failure of traditional knowledge-based intervention strategies. Recent studies have also confirmed this lack of association. Gordon-Larsen conducted a stature-and age-matched pair study to compare various factors including physical activity, dietary intake, eating attitudes, and health knowledge between obese and non-obese adolescents aged 11 to 15 (2001). No significant matched-pair difference was found for the health knowledge score. In a large study based on a random sample of Australian children and adolescents also reported nutritional knowledge was not related to body mass index (O'Dea & Wilson, 2006).

Unlike the results on knowledge and body weight status, no significant disparity in eating behavior scores across the PIBW groups was somewhat unexpected. That is, a logical explanation should be that different body weight status is most likely to be contributed by different eating behaviors. Interestingly, however, the matched pair study by Gordon-Larsen (2001) also failed to find differences in dietary intake between obese and non-obese pairs. The gap between the observation and expectation is not fully understood at this point. Possible explanations may include lack of statistical power from a small sample size, the well-known flat slope syndrome (Gibson, 1990), and inherited limitation of a cross-sectional examination.

It is interesting to notice a gender-specific role of subjective body satisfaction status on the levels of obesity-toward attitudes and practicing eating guidelines. While body satisfaction status was not shown to have anything to do with the attitudes and eating behaviors in boys, our findings suggest it may be a significant factor affecting the attitudes and eating behaviors in girls. Directions of such relations in girls-more negative attitudes toward obesity and less healthy eating behaviors among girls with low body satisfaction level-make interpretation of the findings somewhat puzzling, though. A possible interpretation may be that girls with low body satisfaction levels are highly sensitive to their body weights, thereby build up negative attitudes toward obesity, but lack necessary behavioral skills or will. Based on the interpretation, it is suggested that nutritional educators can use information on body satisfaction status to identify girls requiring more imminent educational attention. In addition, specific and ready-to-applicable behavior-focused messages seem to be needed.

A couple of methodological constraints should be noted in interpreting the study findings. The current study may have limited generalizability because of the small sample size and the use of a convenience sample. The instrument tools to assess degrees of the obesity-toward attitudes, obesity-related knowledge, and practice of the eating behavior guidelines were not previously evaluated for reliability and validity in a population similar to our study subjects, presenting an issue of uncertainty of the findings. Notably though, internal reliability coefficients for the survey sections were found to be high.

In summary, the findings indicated that the level of obesity was not a distinguishing variable in the attitudes, knowledge, and eating behaviors for both boys and girls. Boys did not vary in terms of the attitudes, knowledge, and eating behaviors by body satisfaction status, either. Body satisfaction status was significantly related to girls' attitudes and eating behaviors, though such a relation was not observed for the knowledge. Those with lower body satisfaction were found to possess more negative attitudes toward obesity, but these negative attitudes were, somehow, accompanied by less practice of healthy eating behaviors.

Nutritional educators who promote obesity prevention or reduction among elementary school children can incorporate the results from this study into their intervention programs to improve effectiveness. Based on the findings from this study, a few recommendations for the intervention programs can be made: 1) Educational effort should pay prior attention to help build undistorted perceptions of ideal body shapes and obesity-toward attitudes, especially when targeting girls; 2) Delivering specific and ready-to-applicable behavior-focused messages rather than knowledge-based messages is likely to work better particularly for girls; 3) The messages need to be tailored by girls' body satisfaction status to boost effectiveness, and information on body satisfaction status can be used to identify girls requiring more imminent educational attention; 4) Educational programs should also concern boys in consideration of their higher obesity prevalence. Gender-specific approach is suggested based on our study results. While the body satisfaction-stratified approach is suggested for girls, our study findings support rather universal approach to boys as an economic method without compensating educational effect.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download