Abstract

Metabolic acid-base disorders are comnom clinical problems in ICU patients. Arterial blood gas analysis and anion gap (AG) are important laboratory data in approaching acid-base interpretation. When measuring the AG, several factors such as albumin have influence on unmeasured anions and unmeasured cations. If a patient has hypoalbuminemia, the AG should be adjusted according to the albumin level. High AG metabolic acidoses including lactic acidosis, ketoacidosis, and ingestion of toxic alcohols are common in ICU patients. The treatment target of lactic acidosis and ketoacidosis is not the acidosis, but the underlying condition causing acidosis. Gastric acid loss, diuretics, volume depletion, renal compensation for respiratory acidosis, hypokalemia, and mineralocorticoid excess are common causes of metaboic alkalosis. In chloride responsive metaboic alkalosis, volume and potassium repletion are mandatory.

Acid-base disorders may be the most common clinical problem in the ICU1). This review describes metobolic acidosis with high anion gap (AG), which contains lactic acidosis, ketoacidosis, and toxic ingestion. The final section also describes metabolic alkalosis.

Metablic acidosis is a clinical disturbance characterized by a low arterial pH, a reduced plasma HCO3- concentration, and compensatory hyperventilation. Severe metabolic acidosis represents detrimental clinical effects including hyperventilation, decreased cardiac contractility and cardiac output, cardiac arrhythmia, pulmomary edema with minimal volume overload, and depressed central nervous system (CNS) function.

Plasma HCO3- concentration should be assessed if a patient is suspicious for metabolic acidosis. A low plasma HCO3- concentration, however, is not diagnostic for metabolic acidosis, since it is also generated by renal compensation to chonic respiratory alkalosis. Measurement of the arterial pH can exclude chonic respiratory alkalosis.

The next stage of approach for patients with a metabolic acisois is calculation of serum AG, which is an estimate of increased unmeasured anions (UA) that helps to identify the cause of metabolic acidosis. The AG is used to determine whether metabolic acidosis is a result of an accumulation of non-volatile acids or a net loss of bicarbonate. All ions participate in electrochemical balance, including Na+, Cl-, HCO3-, unmeasured cations (UC) and UA. Thus,

AG = UA - UC = Na+ - (Cl- + HCO3-)

The normal value of the AG was originally set at 12 ± 4 mEq/L. With the adoption of newer automated systems that more accurately measure serum elecrolytes, the normal value of the AG is 7 ± 4 mEq/L2). This is a source of error in the interpretation of the AG.

Another source of error in the interpretation of the AG is albumin. Since hypoalbuminemia is common in ICU patients, the influence of albumin on the AG should be considered in all ICU patients. One of the methods of adjusting the AG in hypoalbuminemic patients is the following equation.

Adjusted AG = Observed AG + 2.5 × [normal albumin - measured albumin (g/dL)]3)

There are two types in metabolic acidosis, a high AG or a normal AG4). High AG metabolic acidosis is caused by addition of fixed acid to the extracellular fluid. The usual causes of high AG metabolic acidosis are lactic acidosis, ketoacidosis, end-stage renal failure, and toxic ingestion, including methanol, propylene glycol, and salicylates. Normal AG metabolic acidosis is a result of loss of HCO3- from the extracellular space, which is counterbalanced by a gain of Cl-. The common causes of a normal AG metabolic acidosis include diarrhea, early renal failure, infusion of large volume isotonic saline, renal tubular acidosis, acetazolamide, and fistulas between ureter and gestrointestinal (GI) tract.

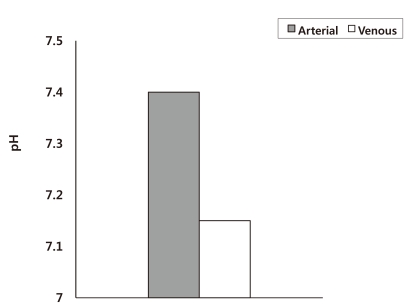

The evaluation of acid-base disorders usually relies on arterial blood gas analysis. However, arterial blood may not be an accurate reflection of the acid-base conditions in peripheral tissues, especially in hemodynamically unstable patients. Weil et al. reported that during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), the arterial blood has a normal pH, while the venous blood shows severe acidemia (pH = 7.15) (Fig. 1)5). Although these results are under extreme conditions, medical personal have to remember that the acid-base status of arterial blood may not be an accurate reflection of the acid-base conditions in peripheral tissues when performing CPR .

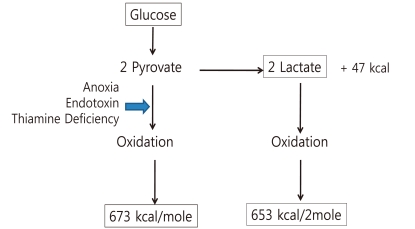

Lactate is the end product of anaerobic glycolysis. The anaerobic metabolism of 1 mole of glucose generates 47 kcal and 2 moles of lactate. The calories are 7% of energy yield from complete oxidation of glucose (673 kcal). Oxidation of 2 moles of lactate generates 652 kcal6). In critically ill patients, lactate generation could be used as a source of energy by the heart and CNS (Fig. 2).

Common etiologies of lactic acidosis in ICU patients are circulatory shock, sepsis, seizures, hepatic insufficiency, acute asthma, and malignancy. Thiamine deficiency and a variety of drugs can produce lactic acidosis including nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, acetaminophen, epinephrine, metformin, propofol, linezolid, and nitroprusside7).

There are many suggestive clues in the history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and response to therapy for the diagnosis of lactic acidosis. AG has to be elevated in lactic acidosis, but there are numerous reports of cases with normal AG lactic acidosis. Thus, AG should not be used as a screening test for lactic acidosis. Blood lactate concentration can be measured and levels above 4-5 mEq/L is abnormal. In patients with sepsis, a blood lactate level above 4 mEq/L may have prognostic value.

The primary goal of therapy in lactic acidosis is correction of the underlying metabolic abnormality. The principal fear of acidosis is that acidosis is a myocardial depressant. The role of HCO3- administration in lactic acidosis, however, has been a source of great controversy. HCO3- therapy has possible risks, including paradoxical intracellular acidosis due to CO2 generation, volume expansion, hypernatremia, and overshoot metabolic alkalosis8). There are several alternatives to HCO3- therapy, such as Carbicarb (Na2CO3 + NaHCO3), THAM (Tris-hydroxymethyl aminomethane), and dichloroacetate. However, published clinical experience with these agents is limited. Therefore, HCO3- has limited roles in the management of lactic acidosis. In the setting of severe acidosis (pH < 7.1) where the patient is deteriorating rapidly, HCO3- infusion can be attempted by administrating one-half of the estimated HCO3- deficit.

HCO3- deficit (mEq) = 0.6 × wt (kg) × (15 - measured HCO3-)

15 mEq/L is the end point for the plasma HCO3- to avoid overshoot alkalosis.

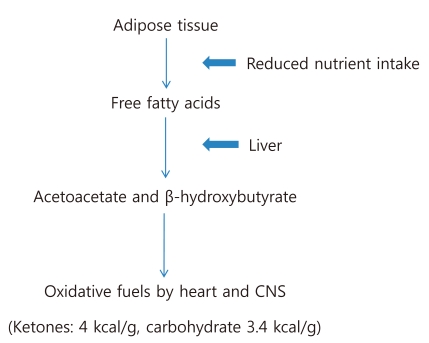

In conditions of reduced nutrient intake, adipose tissue releases free fatty acids, which are converted in the liver into ketones, acetoacetate (AcAc) and β-hydroxybutyrate (β-OHB). Both diminished activity of insulin and enhanced secretion of glucagon contribute to these changes9). Since oxidative metabolism of ketones generates 4 kcal/g, these ketones can be used as an energy source by the heart and CNS (Fig. 3). The normal concentration of ketones in the blood is less than 1 mg/dL, but blood ketone levels increase tenfold after 3 days of starvation. The concentration of AcAc and β-OHB in blood is determined by the following reaction:

AcAc + NADH ↔ β-OHB + NAD

The balance of this reaction favors the right side. The β-OHB : AcAc ratio ranges from 3 : 1 in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), to 8 : 1 in alcoholic ketoacidosis (AKA). The nitroprusside reaction is a commonly used method for detecting AcAc and acetone in blood and urine. A detectable reaction requires a minimum AcAc concentration of 30 mg/dL. Because this reaction does not detect the β-OHB, false negative results will be possible in spite of severe ketoacidosis10).

DKA is combined with hyperglycemia, but it may be mildly elevated or even normal in about 20% of the cases. Patients with AKA tend to be chronically ill and several comorbid conditions may be evident; including hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypophosphatemia, hypomagnesemia, hypoglycemia and mixed acid-base disorders. Initially, the increase in ketoacids produces an elevated AG. Fluid replacement therapy, however, promotes ketoacid excretion in the urine and increases Cl- reabsorption in renal tubules. This can result in low HCO3- concentrations despite resolving ketoacidosis. Therefore, monitoring the ΔAG : ΔHCO3- ratio as therapy can be more informative. 1.0 in this ratio means pure ketoacidosis. The ratio decreases toward 0 as the ketoacidosis is resolved and high AG metabolic acidosis is replaced by the hyperchloremic acidosis. Management of ketoacidosis is intravenous insulin in the case of DKA, infusion of glucose in the case of AKA, volume replacement, and electrolyte replacement. HCO3- therapy does not improve the outcome in ketoacidosis and is not recommended10, 11).

Ethylene glycol is an alcohol solvent used in antifreeze. This is the leading cause of death from chemical agents in the United States. Ethylene glycol is absorbed from the GI tract and metabolized by alcohol dehydrogenase (AD) in the liver producing to glycolic acid. This produces high AG metabolic acidosis. Serum lactate levels are also elevated in ethylene glycol poisoning because the formation of glycolic acid involves the conversion of NAD to NADH and this promotes the conversion of pyruvate to lactate12). The final metabolite of ethylene glycol is oxalic acid, which can react with calcium to form a calcium oxalate complex. Calcium oxalate crystals can damage the renal tubules and produce acute kidney injury.

Clinical presentation of ethylene glycol intoxication is nausea, vomiting, and inebriation, which mimic ethanol intoxication followed by acidosis, pulmonary edema, and cardiopulmonary dysfunction. Oliguric renal failure can be developed 24 hours after ingestion. Laboratory findings show a high AG metabolic acidosis with elevated osmolar gap. Serum lactate levels can be elevated. Hypocalcemia and calcium oxalate crystals in urine are present13).

Therapy is started based on high clinical suspicion. Treatment involves inhibition of AD with fomepizole or ethanol, and hemodialysis if necessary14). Adjunct therapy with thiamine and pyridoxine can divert glyoxylic acid to nontoxic metabolites.

Methanol (wood alcohol) is a common ingredient of shellac, varnish, windshield washer fluid, and solid cooking fuel. Methanol is rapidly absorbed from the GI tract and is metabolized by AD in the liver to formic acid. Tissues particularly susceptible to methanol are retina, optic nerve, and basal ganglia15).

Early signs are signs of inebriation. Many toxic manifestations including visual symptoms (decreased/blurred vision, snowfield blindness, scintillations, photophobia, and total blindness), depressed consciousness, coma, and generalized seizures are delayed 6-24 hours after ingestion. Examination of the eye reveals poorly reactive/unresponsive pupils, reduced acuity, optic disc hyperemia, retinal edema, increased blind spot, papilledema, and late optic atrophy.

Laboratory studies are similar with ethylene glycol intoxication. Pancreatic enzymes can be also elevated and elevated CPK from rhabdomyolysis has been reported.

Treatment is the same as ethylene glycol intoxication. Visual impairment is an indication for dialysis. Adjunct therapy with thiamine and pyridoxine is not indicated15).

Propylene glycol is used as a drug vehicle or diluents to enhance water solubility of many hydrophobic intravenous drugs including lorazepam, diazepam, esmolol, nitroglycerin, and phenytoin. About 45% of propylene glycol is excreted by the kidney and remainder metabolized by the liver. This alcohol is metabolized by AD to lactaldehyde and methylglyoxal, then to lactate and pyruvate16). ICU patients receiving high dose of these drugs for more than 2 days can produce lactic acidosis and acute kidney injury.

Signs of toxicity are agitation, coma, seizures, tachycardia, hypotension, and hyperlactatemia. This condition should be suspected in a patient with unexplained hyperlactatemia who is receiving a continuous infusion of high dose of these drugs for greater than 48 hours.

Treatment is discontinuation of suspected drugs and intermittent hemodialysis16).

Metabolic alkalosis is characterized by increased HCO3- concentration in extracellular space with compensatory increase in arterial PCO2. Loss of gastric secretions, diuretics, volume depletion, hypokalemia, organic anions, and chronic CO2 retention are responsible for most cases of metabolic alkalosis in ICU patients. The clinical consequences of severe metabolic alkalosis are neurologic manifestations, hypoventilation, and decreased systemic oxygenation.

Metabolic alkalosis is classified as chloride-responsive and chloride-resistant, according to the urinary Cl- concentration. Urine Cl- of chloride-responsive metabolic alkalosis is less than 15 mEq/L. Gastric acid loss, remote use of diuretics, volume depletion, and renal compensation for respiratory acidosis are common causes of this type of metabolic alkalosis. Chloride-resistant metabolic alkalosis is characterized by elevated urinary Cl- excretion (above 25 mEq/L). Causes of this type of metabolic alkalosis are mineralocorticoid excess or potassium depletion17).

Most of the metabolic alkalosis seen in ICU patients are chloride responsive. Cl- replacement is important therapy for metabolic alkalosis. Volume of normal saline needed is calculated by estimating the Cl- deficit17).

Cl- deficit (mEq) = 0.2 × wt (kg) × (normal Cl- - actual Cl-)

Volume of saline (L) = Cl- deficit/154

Since hypokalemia can promote metabolic alkalosis, correction of hypokalemia is important for correcting metabolic alkalosis. For patients who have severe metabolic alkalosis (pH > 7.55 with HCO3- > 40 mEq/L) and have failed correction of metabolic alkalosis by saline infusion or potassium replacement, dilute solution of HCl infusion is indicated. The amount of HCl is determined by estimating H+ deficit.

H+ deficit (mEq) = 0.5 × wt (kg) × (actual HCO3- - desired HCO3-)

The HCl solution for intravenous use is 0.1N HCl. It must be infused via central vein and the infusion rate should not exceed 0.2 mEq/kg/hr18). To manage the chloride-resistant metabolic alkalosis caused by mineralocorticoid excess, 5-10 mg/kg of acetazolamide can be used. Acetazolamide promotes potassium depletion and volume depletion19).

References

1. Gauthier PM, Szerlip HM. Metabolic acidosis in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 2002; 18:289–308. PMID: 12053835.

2. Winter SD, Pearson JR, Gabow PA, Schultz AL, Lepoff RB. The fall of the serum anion gap. Arch Intern Med. 1990; 150:311–313. PMID: 2302006.

3. Figge J, Jabor A, Kazda A, Fencl V. Anion gap and hypoalbuminemia. Crit Care Med. 1998; 26:1807–1810. PMID: 9824071.

4. Casaletto JJ. Differential diagnosis of metabolic acidosis. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005; 23:771–787. PMID: 15982545.

5. Weil MH, Rackow EC, Trevino R, Grundler W, Falk JL, Griffel MI. Difference in acid-base state between venous and arterial blood during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1986; 315:153–156. PMID: 3088448.

6. Brooks GA. Lactate production under fully aerobic conditions: the lactate shuttle during rest and exercise. Fed Proc. 1986; 45:2924–2929. PMID: 3536591.

7. Mizock BA, Falk JL. Lactic acidosis in critical illness. Crit Care Med. 1992; 20:80–93. PMID: 1309494.

8. Forsythe SM, Schmidt GA. Sodium bicarbonate for the treatment of lactic acidosis. Chest. 2000; 117:260–267. PMID: 10631227.

10. Charfen MA, Fernandez-Frackelton M. Diabetic ketoacidosis. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005; 23:609–628. PMID: 15982537.

11. Wrenn KD, Slovis CM, Minion GE, Rutkowski R. The syndrome of alcoholic ketoacidosis. Am J Med. 1991; 91:119–128. PMID: 1867237.

12. Gabow PA, Clay K, Sullivan JB, Lepoff R. Organic acids in ethylene glycol intoxication. Ann Intern Med. 1986; 105:16–20. PMID: 3717806.

13. Caravati EM, Erdman AR, Christianson G, et al. Ethylene glycol exposure: an evidence-based consensus guideline for out-of-hospital management. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2005; 43:327–345. PMID: 16235508.

14. Oh MS. Unconventional views on certain aspects of toxin-induced metabolic acidosis. Electrolyte Blood Press. 2010; 8:32–37.

15. Barceloux DG, Bond GR, Krenzelok EP, Cooper H, Vale JA. American Academy of Clinical Toxicology practice guidelines on the treatment of methanol poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2002; 40:415–446. PMID: 12216995.

16. Wilson KC, Reardon C, Theodore AC, Farber HW. Propylene glycol toxicity: a severe iatrogenic illness in ICU patients receiving IV benzodiazepines: a case series and prospective, observational pilot study. Chest. 2005; 128:1674–1681. PMID: 16162774.

18. Brimioulle S, Vincent JL, Dufaye P, Berre J, Degaute JP, Kahn RJ. Hydrochloric acid infusion for treatment of metabolic alkalosis: effects on acid-base balance and oxygenation. Crit Care Med. 1985; 13:738–742. PMID: 3928258.

19. Marik PE, Kussman BD, Lipman J, Kraus P. Acetazolamide in the treatment of metabolic alkalosis in critically ill patients. Heart Lung. 1991; 20:455–459. PMID: 1894525.

Fig. 1

The pH in Arterial and Venous Blood during Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

*Modified from the study of Weil MH et al. Ref. 5.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download