Abstract

Humeral medial epicondyle fractures constitute around 15% of pediatric elbow fractures. Up to 60% occur in association with elbow dislocations. Knowledge of potential imaging pitfalls when examining acute elbow fractures in children contributes significantly to accurate diagnosis. Nevertheless, management of missed pediatric medial epicondyle fractures has rarely been reported. We present an 11-year-old boy with a neglected and severely displaced medial epicondyle fracture with concurrent ulnar nerve palsy. We performed neural decompression, fragment excision, and muscular and capsuloligamentous reconstruction of the medial elbow. This study demonstrates that the surgical outcome of a late presenting fracture can be satisfactory in terms of function and neural recovery. It also underscores the importance of careful interpretation of elbow imaging including normal anatomic variants.

Medial epicondyle fractures of the distal humerus constitute 10%–15% of pediatric elbow fractures. These injuries frequently occur in association with intra-articular incarceration of the fracture fragment, elbow dislocation, ulnar nerve insult, and other upper limb fractures.12) These fractures are more common in boys. The peak age of occurrence is 11 to 12 years.12) Medial epicondyle fractures often occur as a result of an avulsion force and less frequently due to direct trauma.12) Medial epicondyle fractures have been classified into four types depending on the extent of medial epicondyle displacement and the presence of a concomitant dislocation: a small degree of avulsion (type I), a non-entrapped avulsed fragment at the level of the joint (type II), a fragment incarcerated in the joint (type III), and a fracture associated with elbow dislocation (type IV).3) A large systematic review on pediatric medial epicondyle fractures estimated the incidence of coexistent preoperative ulnar nerve affection in the acute setting to be 9.6%.4) Nevertheless, late presenting medial epicondyle fractures in association with preoperative ulnar nerve affection is extremely rare.56) The outcome and complications of such an injury pattern have been reported only twice in the English literature.56) The sophisticated developmental anatomy of the pediatric elbow may lead to misinterpretation of radiographs in the phase of acute trauma. Consequently, delayed diagnosis and institution of faulty treatment may be fraught with unfavorable prognosis and a potentially higher complication rate.156) The goal of this study is to underscore the extreme importance of accurate radioclinical evaluation of the acutely traumatized pediatric elbow. The specific aim is to reveal the functional outcome and potential for neural recovery of an 11-year-old boy with a neglected and severely displaced medial epicondyle fracture associated with ulnar nerve palsy.

The study was tacitly approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ain-Shams University Hospitals and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from the patient and his parents for being included in the study.

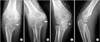

An 11-year-old boy presented to Pediatric Orthopedic of Ain-Shams University Hospitals complaining of painful restriction of right elbow motion 7 weeks after falling on his outstretched hand. The patient was initially managed by a posterior slab at another hospital based upon a provisional diagnosis of elbow sprain. On examination the right elbow was diffusely swollen and tender especially medially with a valgus attitude. We observed marked painful restriction of range of motion (ROM) at elbow, ranging 40°–80°. Forearm rotation was spared. We encountered classic signs of motor and sensory high ulnar nerve palsy. Orthogonal and oblique radiographs were taken of the elbow, and full forearm and elbow computed tomography scans were three-dimensional reformatted (Figs. 1 and 2). We decided to operate on the patient based on the presence of marked fracture displacement, ulnar nerve palsy, severe motion block at the elbow, and presumed valgus instability. We employed a classic medial approach to the elbow. The ulnar nerve was freed from adhesions. It was found to be subluxed with a significant localized swollen and contused segment commencing at the joint line just above the avulsed epicondylar fragment and extending proximally. The continuity of the nerve was preserved. We found the medial epicondyle avulsed from its bed and located at the level of the humeroulnar articulation strictly juxta-capsular. We excised the fragment. The humeroulnar articulation was inspected for cartilaginous fragments and the capsule and collaterals were sutured. The common flexor origin was reattached to the fracture bed by means of interosseous and posterior humeral periosteal sutures. The nerve was relocated into the anatomical position (Fig. 3).

A posterior slab was applied to the elbow in 90° flexion for 3 weeks. Then, a hinged elbow brace was applied for another 3 weeks permitting early gradual passive and assisted active ROM at the elbow. The patient was followed up for 1 year. We used the Mayo elbow performance score (MEPS) to assess postoperative functional outcome. In a recent study, the MEPS has been shown to be a reliable and accurate outcome instrument of elbow function.7) The MEPS measures four domains: pain, flexion arc, stability, and function. The total score is calculated to range from 0 (worst/poor) to 100 (best/excellent). Our patient exhibited complete pain relief, a flexion arc of 105° (10° to 115°), a stable elbow, especially to valgus stress in 20° of flexion, and no difficulty in executing activities of daily living; thus, his elbow performance was categorized as excellent. The ulnar nerve demonstrated full recovery of sensory and motor components, including recovery of the sensory distribution in the hand, finger clawing, first dorsal interosseous wasting, ulnar intrinsic muscles, and hypothenar muscle strength. Hand grip strength was normal. No symptoms or signs suggestive of ulnar nerve subluxation/snapping were encountered. These findings were verified by dynamic ultrasound examination. The ulnar nerve ultrasound showed residual segment contusion correlating with that shown on intraoperative images. The final postoperative radiographs, computed tomography scans, and ultrasound images are shown in Fig. 4.

Multiple radioclinical classification systems have been proposed for pediatric medial epicondyle fractures.124) However, no classification system takes into consideration the time elapsed from an acute injury to presentation. Although missed medial epicondylar fractures appear to be rare in the English literature,56) we deduce that such injuries may be considerably underreported. There are only two publications that report missed medial epicondylar fractures with coexistent ulnar nerve palsy with a time lag between the initial injury and presentation of 125) and 8 weeks after injury,6) respectively. These two case reports were associated with an elbow dislocation that was initially reduced by closed reduction. Interestingly, the incarcerated medial epicondylar fragment was not diagnosed due to misinterpretation of initial plain films and both cases presented with late ulnar nerve dysfunction.56) We encountered a similar clinical scenario in our patient except for the absence of concurrent elbow dislocation. Additionally, our patient did not have a typical intra-articular fragment incarceration. He had a fragment that was displaced to the level of the medial joint line strictly juxta-capsular. It is our assumption that capsular penetration or irritation by the fracture fragment significantly contributed to the marked motion block of the elbow when the patient presented to us.

The two above-mentioned reports56) demonstrated a satisfactory functional outcome and full ulnar nerve recovery following neural decompression. Furthermore, Lima et al.5) performed anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve and anatomic fragment reposition with a screw, in contrast to Haflah et al.6) who performed excision of epicondylar fragment without ulnar nerve transposition. The satisfactory functional results and full restoration of ulnar nerve deficits obtained in our patient are in line with those described in these two previous reports.56) We adopted a similar surgical strategy to that of Haflah et al.6) with regard to fragment excision without ulnar nerve transposition. We opted for excision of the compressing epicondylar fragment because of concerns about fragment size, vascularity, and potential fixation problems. We observed no valgus elbow instability, and a pain free elbow with inconsequential restriction of ROM. We found no symptoms suggestive of ulnar nerve subluxation. The complexity of radiographic evaluation of the pediatric elbow stems from the variable appearance and fusion of ossification centers. The trochlear ossification most often has a fragmented and irregular appearance and may resemble a traumatic intra-articular pathology.128) The final postoperative radiographs of our case depicted an irregular and fragmented appearance of the trochlear epiphysis that was almost fully cartilaginous and subtle on the preoperative radiographs. This described ossification pattern was clearly preceding the trochlear ossification of the uninjured elbow at the final follow-up. We speculate that such findings may be secondary to the accident and surgical trauma inflicted upon the injured elbow. Such trauma may have triggered the ossification process with regard to the timing of eruption and magnitude. Another explanation would be the reported occurrence of asymmetrical radiographic appearance of ossification centres within the same child.8)

The findings of our study and the two comparable publications lend support to the conclusion that in cases of neglected severely displaced pediatric medial epicondylar fractures with ulnar nerve dysfunction, a satisfactory functional outcome may be an achievable goal. There is a potential for full neural recovery following decompression and repair of medial stabilizers of the elbow. Misreading the radiographs of pediatric elbow injuries in the acute phase may prolong the treatment course and complicate management strategies.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Preoperative plain radiographs of the right elbow. Note that various degrees of forearm rotation in the anteroposterior (A, B, C) and oblique views (D) affect medial epicondylar fragment visualization (arrows). The depicted epicondylar fragment was shown to be equivalent in size to that of the normal elbow (see Fig. 4E). |

| Fig. 2Three-dimensional volume rendering computed tomography images (A, B) are apparently impressive of intra-articular fragment location. Note widening of the humeroulnar joint space. |

| Fig. 3Ulnar nerve status. (A) Intraoperative image. Note the contused segment (arrows) of the ulnar nerve, the retracted stump of the flexor-pronator mass after fragment excision (hollow arrow), and the medial epicondyle fracture bed (arrow head). (B) Preoperative photograph showing ulnar clawing. (C) One-year postoperative photograph demonstrating full resolution. |

| Fig. 4One-year follow-up imaging evaluation. Note the irregular fragmented appearance of the trochlear epiphysis (arrows) in the anteroposterior radiograph (A) and axial (B), sagittal (C), and coronal (D) computed tomography images. (E) Anteroposterior radiograph of the normal left elbow at the same follow-up session. Note the ossified medial epicondylar fragment (arrow) and absent trochlear epiphysis ossification. (F) Longitudinal ultrasound images of the right (RT) and left (LT) common flexor origin showing fanning of the right (injured) one due to reattachment. |

References

1. Pathy R, Dodwell ER. Medial epicondyle fractures in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015; 27(1):58–66.

2. Gottschalk HP, Eisner E, Hosalkar HS. Medial epicondyle fractures in the pediatric population. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012; 20(4):223–232.

3. Papavasiliou VA. Fracture-separation of the medial epicondylar epiphysis of the elbow joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982; (171):172–174.

4. Kamath AF, Baldwin K, Horneff J, Hosalkar HS. Operative versus non-operative management of pediatric medial epicondyle fractures: a systematic review. J Child Orthop. 2009; 3(5):345–357.

5. Lima S, Correia JF, Ribeiro RP, et al. A rare case of elbow dislocation associated with unrecognized fracture of medial epicondyle and delayed ulnar neuropathy in pediatric age. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013; 22(3):e9–e11.

6. Haflah NH, Ibrahim S, Sapuan J, Abdullah S. An elbow dislocation in a child with missed medial epicondyle fracture and late ulnar nerve palsy. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2010; 19(5):459–461.

7. Cusick MC, Bonnaig NS, Azar FM, Mauck BM, Smith RA, Throckmorton TW. Accuracy and reliability of the Mayo Elbow Performance Score. J Hand Surg Am. 2014; 39(6):1146–1150.

8. Keats TE, Anderson MW. Atlas of normal roentgen variants that may simulate disease. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders;2012.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download