This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to compare the results of arthroscopically guided suprascapular nerve block (SSNB) and blinded axillary nerve block with those of blinded SSNB in terms of postoperative pain and satisfaction within the first 48 hours after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair.

Methods

Forty patients who underwent arthroscopic rotator cuff repair for medium-sized full thickness rotator cuff tears were included in this study. Among them, 20 patients were randomly assigned to group 1 and preemptively underwent blinded SSNB and axillary nerve block of 10 mL 0.25% ropivacaine and received arthroscopically guided SSNB with 10 mL of 0.25% ropivacaine. The other 20 patients were assigned to group 2 and received blinded SSNB with 10 mL of 0.25% ropivacaine. Visual analog scale (VAS) score for pain and patient satisfaction score were assessed 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours postoperatively.

Results

The mean VAS score for pain was significantly lower 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours postoperatively in group 1 (group 1 vs. group 2; 5.2 vs. 7.4, 4.1 vs. 6.1, 3.0 vs. 5.1, 2.1 vs. 4.2, 0.9 vs. 3.9, and 1.3 vs. 3.3, respectively). The mean patient satisfaction score was significantly higher at postoperative 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours in group 1 (group 1 vs. group 2; 6.7 vs. 3.9, 7.4 vs. 5.1, 8.8 vs. 5.9, 9.2 vs. 6.7, 9.5 vs. 6.9, and 9.0 vs. 7.2, respectively).

Conclusions

Arthroscopically guided SSNB and blinded axillary nerve block in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair for medium-sized rotator cuff tears provided more improvement in VAS for pain and greater patient satisfaction in the first 48 postoperative hours than blinded SSNB.

Go to :

Keywords: Nerve block, Rotator cuff, Suprascapular nerve block, Rotator cuff tear arthropathy

Approximately 30%–70% of patients undergo severe postoperative pain after shoulder surgery.

12) Boss et al.

3) described that severe postoperative pain is frequently observed after rotator cuff repair particularly within the first 48 postoperative hours.

2) This postoperative pain is difficult to manage, but it should be managed with an early recovery procedure.

12) Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is one of the most commonly utilized postoperative pain control method; however, it has been frequently associated with adverse reactions, such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and sedation.

45) Local and regional blocks, such as interscalene brachial plexus block (IBPB), suprascapular nerve block (SSNB), and axillary nerve block (ANB), have been recommended to decrease postoperative pain in arthroscopic shoulder surgery.

5) IBPB has been demonstrated as one of the most efficient pain management tools among regional blocks for shoulder surgery.

6) However, it can bring about potentially grievous complications of the central or the peripheral nervous system.

5) Complications documented in the literature include rebound pain, failure in nerve block, and phrenic nerve palsy.

67) ANB is a recently introduced regional block procedure for shoulder pain control; however, the sensory area of the axillary nerve supplies only the lateral side of the shoulder.

58) The most widely used regional block for alleviating pain associated with shoulder surgery is SSNB.

258) Approximately 70% of the sensory nerves to the shoulder joint is supplied by the suprascapular nerve (SSN).

59)

The effects of SSNB have been well demonstrated in respective articles.

1011) However, this study is the first to compare SSNB performed under the guidance of arthroscopy and unguided SSNB.

The purpose of this study was to compare the outcomes of arthroscopically guided SSNB with those of unguided SSNB in terms of postoperative pain and satisfaction within the first 48 hours after arthroscopic repair in patients who had medium-sized full thickness rotator cuff tears. Our hypothesis was that arthroscopic guidance would facilitate efficient regional block for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair within 48 postoperative hours.

METHODS

A power analysis suggested that a total sample size of 36 patients (18 patients in each group) be sufficient to achieve a statistical power of 99% with a 2-sided α level of 0.05 to notice significant differences in the visual analog scale (VAS) score for postoperative pain at 8 hours after surgery, presuming an effect size of 1.58 (mean difference, 2.6; standard deviation, 1.7). The power analysis was based on a pilot study where the mean and standard deviation of VAS at 8 hours postoperatively was assessed in 18 patients.

Symptomatic medium-sized full thickness rotator cuff tears were repaired arthroscopically by a senior author (SHK) when the conservative and exercise treatment failed. Between January 2014 and July 2014, 40 patients who underwent arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs for medium-sized full thickness tears were included in the present study. Twenty patients were randomly assigned to group 1 and received arthroscopically guided SSNB and blinded axillary nerve block with 10 mL of ropivacaine. The other 20 patients were assigned to group 2 and received unguided SSNB with 10 mL of ropivacaine before arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Written informed consents were obtained from all patients to take part in this study and the Institutional Review Board of Ulsan University Hospital approved the study (No. 2015-09-021).

Patients with known stiffness, pre-existing suprascapular dyskinesis, glenohumeral arthritis, fracture around the shoulder, or any history of allergy to local analgesic agents were excluded. The inclusion criteria of our study were as follows: (1) a medium-sized full thickness rotator cuff tear that needed repair on preoperative magnetic resonance imaging and detailed radiological and physical examinations; (2) patients who received an intraoperative (group 1) or preoperative (group 2) regional block; and (3) more than 20 years of age. Patients were excluded if they (1) had a history of previous shoulder surgery and fractures around the shoulder; (2) had a concomitant neurologic disorder in the shoulder; and (3) stopped PCA before 48 hours postoperatively due to its adverse effects. Initially, 48 patients scheduled for rotator cuff tear repair were eligible to participate in the study, and all of them met the inclusion criteria. However, 2 patients rejected to participate and thus was excluded. Another patient had a previous history of lateral end fracture of the clavicle in the affected shoulder, and so the patient was excluded.

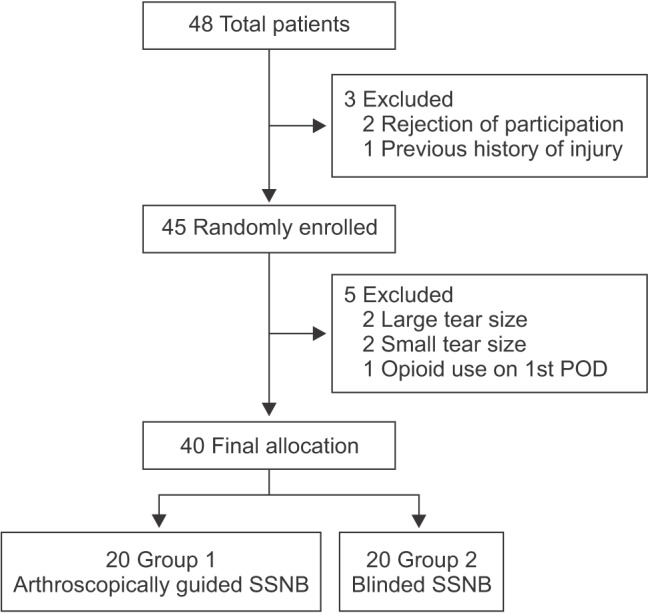

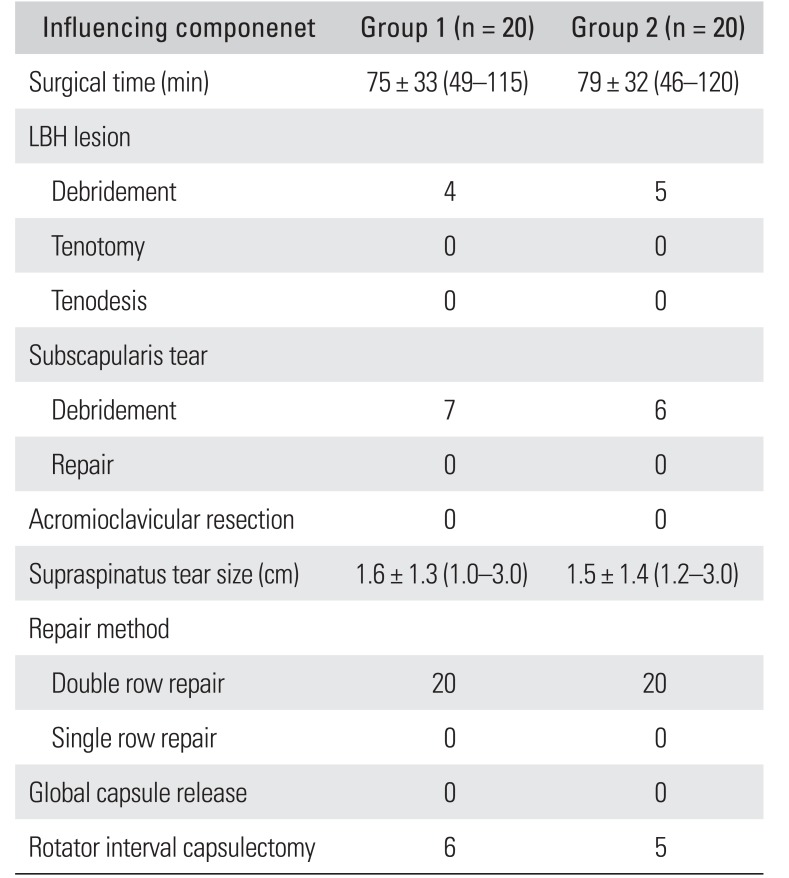

A computerized random sequence generator was used for randomization before surgery by an independent observer. The nurses, medical staff, patients, and research assistants were blinded to the mixtures of syringes used to administer the SSNB for double blinding. An independent observer prepared the syringes and passed them to a scrub nurse who was not involved in our study. Excluding the 3 patients, 45 enrollees were randomly assigned to each group. The patients, surgeons, and nurses who participated in the surgery were blinded to the group assignment. During the operation, 2 patients with an extending tear for shaving and a large-sized rotator cuff tear and another 2 patients with a small-sized rotator cuff tear were excluded from our study. One patient was also excluded because injection of opioid was requested by the patient due to severe postoperative pain on the day after surgery. Ultimately, 40 patients were included in our study. Among them, 20 patients were assigned to group 1 and the other 20 patients to group 2 (

Fig. 1).

| Fig. 1Flowchart for patient enrollment. POD: postoperative day, SSNB: suprascapular nerve block.

|

VAS score for pain, University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) shoulder score, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) shoulder score, Korean Shoulder Elbow Society (KSS) shoulder score, height, and weight were assessed before surgery.

The SPSS ver. 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis with a significance level set at p < 0.05. The collected data exhibited normal distribution in both groups. Statistical analyses were preformed using a student t-test for independent samples and a nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-test.

Surgical Techniques

Patients were placed in the beach chair position in the operating room. Preemptive SSNB, axillary nerve block and intraoperative SSNB were performed under arthroscopic guidance in group 1 and preoperative SSNB was performed without guidance in group 2. PCA was set at a fixed dose: continuous dose, 0.5 mL/hr; total volume, 60 mL (fentanyl + necupam + normal saline [NS] + Nasea injection [0.6 mg; PT Astellas Pharma Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia]); loading dose, 0.5 mL; and lockout time, 15 min. If an increment of the VAS score for pain was observed in the patient between 1 and 48 hours after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, rebounding postoperative pain was suspected.

210) VAS score for pain, satisfaction score of the patients was measured 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours postoperatively. VAS score for pain was rated from 0 (no pain) to 10 (most severe pain).

2) Satisfaction score of the patients was also rated from 0 (unsatisfactory) to 10 (most satisfactory).

5)

In group 2, SSNB was performed preoperatively without arthroscopic guidance. The patient was seated in a 70-degree beach chair position (

Fig. 2). After skin preparation with povidone-iodine, one senior author (SHK) injected 10 mL of 0.25% ropivacaine,

1213) using a 25-gauge spinal needle. The entry point of the SSNB was the midpoint between the anterolateral margin of the acromion and the medial end of the scapular spine (

Fig. 3). When the spinal needle penetrated the transverse scapular ligament, the suprascapular notch was identified and the syringe was retracted slightly to prevent arterial injection because the suprascapular artery was located just above the suprascapular notch. To avoid the possibility of diffusion of the anesthetic solution to the anterior and posterior aspects in the intraarticular space, the needle was placed on the suprascapular notch during injection.

| Fig. 2Beach chair position.

|

| Fig. 3Suprascapular nerve block (SSNB) was performed before surgical procedure in group 2 with the patient positioned in a beach chair. The X mark indicates the introducing point of SSNB, which is located in the middle between the anterolateral edge of the acromion and the superior edge of the medial scapular spine. Bony landmark was outlined with blue line.

|

In group 1, SSNB was performed under arthroscopic guidance. The patient was placed in the beach chair position under general anesthesia. The superficial anatomy and bony landmarks of the shoulder were identified to outline the acromion, the scapular spine, the clavicle, and the coracoid process. The SSN and axillary regional blocks were performed preemptively. The entry point of the axillary nerve block was the intersection between a transverse line 2 cm above the axillary fold and a vertical line below the posterolateral margin of the acromion. At approximately 1.5 cm medial and 2 cm inferior to the posterolateral edge of the acromion, a standard viewing portal was made, and the blunt trocar and obturator were inserted through it. An arthroscope was introduced and a diagnostic arthroscopy was carried out. In patients who required arthroscopic subacromial decompression with acromioplasty, the coracohumeral ligament was released behind the coracoid. Under visualization through the posterolateral, the vascularized fat pad and soft tissue were removed through the anterolateral or Neviser portal using a radiofrequency device (VAPR; DePuy, Raynham, MA, USA) or a shaver alternatively. The transverse scapular ligament (TSL) was identified just medial to the base of coracoid process and the coracoclavicular ligament (trapezoid and conoid ligaments). However, TSL release was not performed because the SSN was protected by a small elevator or a Wissinger rod (Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) through the Neviser portal. A 20-gauge Hemovac catheter was introduced

via the Neviser portal into the suprascapular notch adjacent to the SSN. A bolus of 10 mL of 0.25% ropivacaine was injected adjacent to the SSN. Repeated injection was performed 12 hours interval. Then, arthroscopic rotator cuff repair was performed using suture anchors (

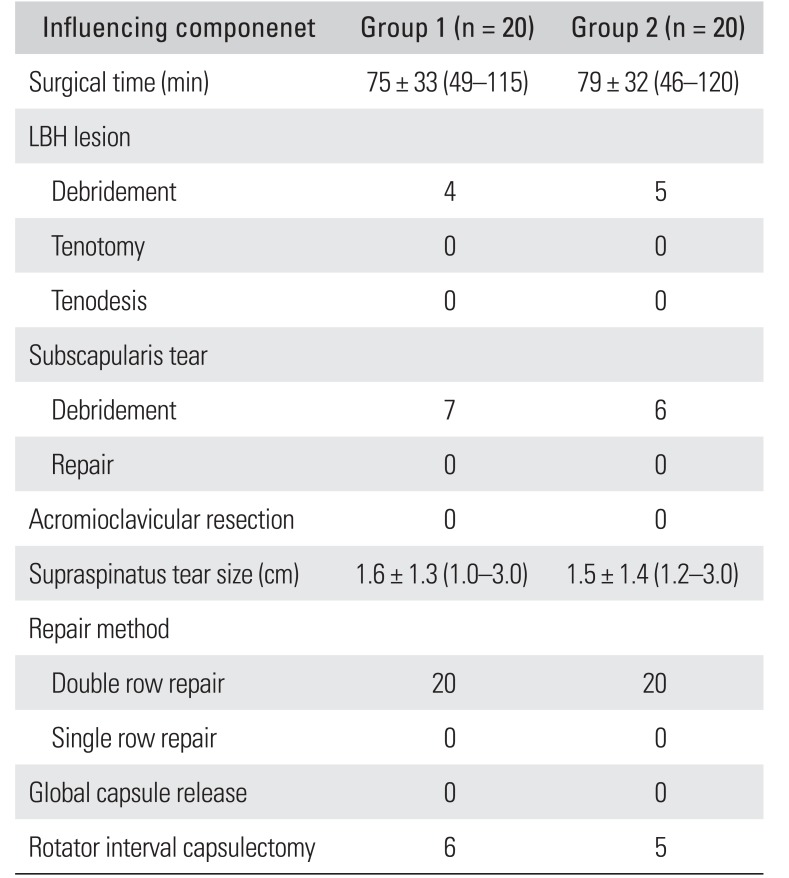

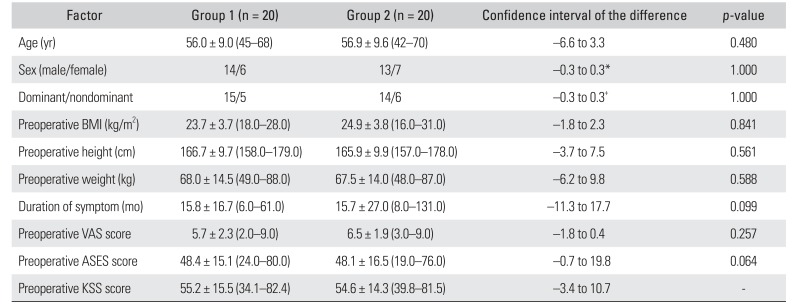

Table 1).

Table 1

Features of the Surgery

|

Influencing componenet |

Group 1 (n = 20) |

Group 2 (n = 20) |

|

Surgical time (min) |

75 ± 33 (49–115) |

79 ± 32 (46–120) |

|

LBH lesion |

|

|

|

Debridement |

4 |

5 |

|

Tenotomy |

0 |

0 |

|

Tenodesis |

0 |

0 |

|

Subscapularis tear |

|

|

|

Debridement |

7 |

6 |

|

Repair |

0 |

0 |

|

Acromioclavicular resection |

0 |

0 |

|

Supraspinatus tear size (cm) |

1.6 ± 1.3 (1.0–3.0) |

1.5 ± 1.4 (1.2–3.0) |

|

Repair method |

|

|

|

Double row repair |

20 |

20 |

|

Single row repair |

0 |

0 |

|

Global capsule release |

0 |

0 |

|

Rotator interval capsulectomy |

6 |

5 |

Subacromial decompression and arthroscopic rotator cuff repair were conducted in all patients who were enrolled in this study. The same senior surgeon (SHK) who specialized in shoulder and sports medicine performed all procedures. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair was performed using a 5.0-mm Bio-Corkscrew suture anchor (Arthrex) and a 4.75-mm Bio-SwiveLock (Arthrex).

Postoperative Care

The cannula was removed at 48 hours after surgery. The operated shoulders were protected with the UltraSling (DJO Global, Vista, CA, USA) for 6 postoperative weeks, and the same postoperative exercises were prescribed in both groups.

The rehabilitation program including postoperative exercises was personalized according to the tissue quality of the medium-sized rotator cuff tear. An abduction pillow brace was used for shoulder immobilization in all patients postoperatively, and patients were cautioned to keep the shoulder in neutral rotation and 40° abduction.

Go to :

RESULTS

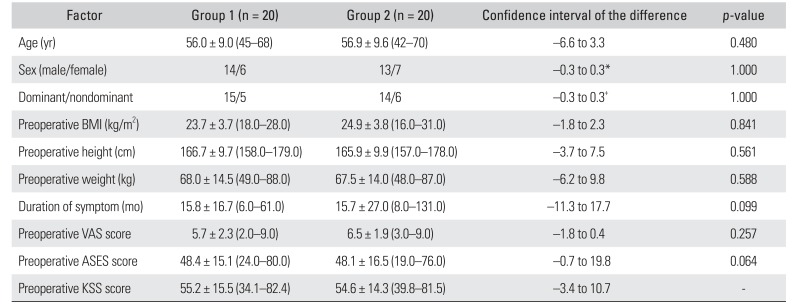

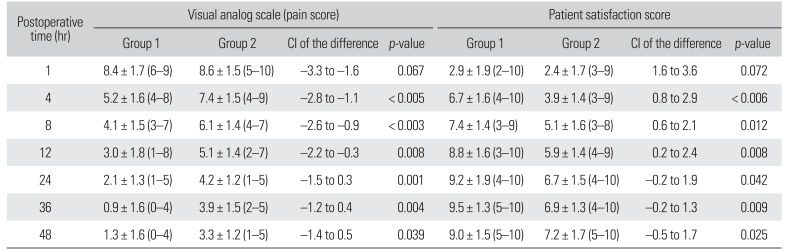

The overall demographic data, such as the symptom duration, mean age, preoperative VAS, ASES, UCLA, KSS, and body mass index (BMI), demonstrated no statistically significant differences between 2 groups. In group 1, the mean patient age was 56.0 ± 9.0 years (range, 45 to 68 years), and the mean BMI was 23.7 ± 3.7 kg/m

2 (range, 18.0 to 28.0 kg/m

2). In group 2, the mean age was 56.9 ± 9.6 years (range, 42 to 70 years) and the mean BMI was 24.9 ± 3.8 kg/m

2 (range, 16.0 to 31.0 kg/m

2) (

Table 2).

Table 2

Patient Demographics

|

Factor |

Group 1 (n = 20) |

Group 2 (n = 20) |

Confidence interval of the difference |

p-value |

|

Age (yr) |

56.0 ± 9.0 (45–68) |

56.9 ± 9.6 (42–70) |

–6.6 to 3.3 |

0.480 |

|

Sex (male/female) |

14/6 |

13/7 |

–0.3 to 0.3*

|

1.000 |

|

Dominant/nondominant |

15/5 |

14/6 |

–0.3 to 0.3+

|

1.000 |

|

Preoperative BMI (kg/m2) |

23.7 ± 3.7 (18.0–28.0) |

24.9 ± 3.8 (16.0–31.0) |

–1.8 to 2.3 |

0.841 |

|

Preoperative height (cm) |

166.7 ± 9.7 (158.0–179.0) |

165.9 ± 9.9 (157.0–178.0) |

–3.7 to 7.5 |

0.561 |

|

Preoperative weight (kg) |

68.0 ± 14.5 (49.0–88.0) |

67.5 ± 14.0 (48.0–87.0) |

–6.2 to 9.8 |

0.588 |

|

Duration of symptom (mo) |

15.8 ± 16.7 (6.0–61.0) |

15.7 ± 27.0 (8.0–131.0) |

–11.3 to 17.7 |

0.099 |

|

Preoperative VAS score |

5.7 ± 2.3 (2.0–9.0) |

6.5 ± 1.9 (3.0–9.0) |

–1.8 to 0.4 |

0.257 |

|

Preoperative ASES score |

48.4 ± 15.1 (24.0–80.0) |

48.1 ± 16.5 (19.0–76.0) |

–0.7 to 19.8 |

0.064 |

|

Preoperative KSS score |

55.2 ± 15.5 (34.1–82.4) |

54.6 ± 14.3 (39.8–81.5) |

–3.4 to 10.7 |

- |

There was no statistically significant difference in age, sex, weight, and height between group 1 and 2. One patient in group 1 and 2 patients in group 2 had nausea; however, the nausea was tolerable in all cases. Other complications, such as paresthesia, were not noticed until at least 3 months postoperatively.

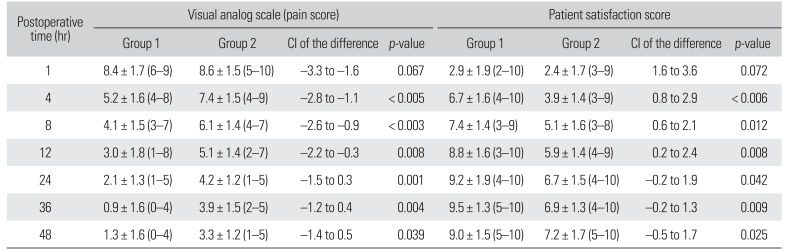

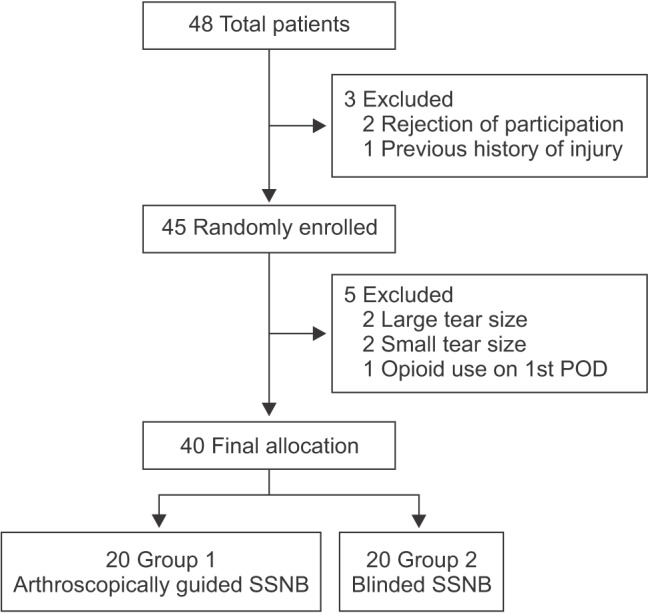

The mean postoperative satisfaction score of patients showed a progressive increment over time, whereas the mean postoperative VAS score demonstrated a progressive decrement in both groups (

Table 3).

Table 3

Visual Analog Scale Score and Patient Satisfaction Score of the Two Groups

|

Postoperative time (hr) |

Visual analog scale (pain score) |

Patient satisfaction score |

|

Group 1 |

Group 2 |

CI of the difference |

p-value |

Group 1 |

Group 2 |

CI of the difference |

p-value |

|

1 |

8.4 ± 1.7 (6–9) |

8.6 ± 1.5 (5–10) |

–3.3 to –1.6 |

0.067 |

2.9 ± 1.9 (2–10) |

2.4 ± 1.7 (3–9) |

1.6 to 3.6 |

0.072 |

|

4 |

5.2 ± 1.6 (4–8) |

7.4 ± 1.5 (4–9) |

–2.8 to –1.1 |

< 0.005 |

6.7 ± 1.6 (4–10) |

3.9 ± 1.4 (3–9) |

0.8 to 2.9 |

< 0.006 |

|

8 |

4.1 ± 1.5 (3–7) |

6.1 ± 1.4 (4–7) |

–2.6 to –0.9 |

< 0.003 |

7.4 ± 1.4 (3–9) |

5.1 ± 1.6 (3–8) |

0.6 to 2.1 |

0.012 |

|

12 |

3.0 ± 1.8 (1–8) |

5.1 ± 1.4 (2–7) |

–2.2 to –0.3 |

0.008 |

8.8 ± 1.6 (3–10) |

5.9 ± 1.4 (4–9) |

0.2 to 2.4 |

0.008 |

|

24 |

2.1 ± 1.3 (1–5) |

4.2 ± 1.2 (1–5) |

–1.5 to 0.3 |

0.001 |

9.2 ± 1.9 (4–10) |

6.7 ± 1.5 (4–10) |

–0.2 to 1.9 |

0.042 |

|

36 |

0.9 ± 1.6 (0–4) |

3.9 ± 1.5 (2–5) |

–1.2 to 0.4 |

0.004 |

9.5 ± 1.3 (5–10) |

6.9 ± 1.3 (4–10) |

–0.2 to 1.3 |

0.009 |

|

48 |

1.3 ± 1.6 (0–4) |

3.3 ± 1.2 (1–5) |

–1.4 to 0.5 |

0.039 |

9.0 ± 1.5 (5–10) |

7.2 ± 1.7 (5–10) |

–0.5 to 1.7 |

0.025 |

The mean VAS score at postoperative 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours was significantly lower (p < 0.005, p < 0.003, p = 0.008, p = 0.001, p = 0.004, and p = 0.039, respectively) in group 1 than group 2. The mean satisfaction score at postoperative 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours (p < 0.006, p = 0.012, p = 0.008, p = 0.042, p = 0.009, and p = 0.025, respectively) was significantly higher in group 1 than group 2.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

The principal finding of this study was that SSNB under arthroscopic guidance and preemptive blinded SSNB and axillary nerve block was more effective for postoperative pain management after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair than blinded SSNB.

In spite of pain management with multimodal analgesia, one third of patients with arthroscopic rotator cuff repair experience severe postoperative pain on the first day after surgery.

14) Immediate management of postoperative pain would be important for early rehabilitation and could significantly decrease the duration of admission after arthroscopic shoulder surgery. The duration of postoperative stay in patients who have arthroscopic shoulder surgery is mainly determined by excessive pain.

15) Thus, appropriate postoperative pain control is one of the major factors that can influence the length of stay.

16)

In shoulder surgery, a continuous infusion pump of analgesia has been described as an effective tool for postoperative pain management. However, in recent reports by Schwartzberg et al.

17) and Coghlan et al.,

18) the use of a continuous subacromial infusion pump resulted in no detectable pain reduction after arthroscopic shoulder surgery. In addition, some complications have been reported, such as leakage, infection, and chondrolysis.

151920) On the other hand, Busfield et al.

21) reported that the subacromial pain pumps could be used safely in arthroscopic shoulder surgery in the short-term, and the only complication was external catheter breakage. In our study, we used a single bolus infusion in our patients. The most effective tool for postoperative pain control is known as interscalene brachial plexus block (ISB), but it showed a relatively short duration compared with SSNB. DeMarco et al.

22) reported that the benefit of ISB for postoperative pain control disappeared 12 hours after surgery. In addition, it has often been associated with complications, such as phrenic nerve palsy

267) and delayed vocal fold paralysis.

23)

SSNB is another type of peripheral nerve block that is most widely used and provides pain relief in arthroscopic shoulder surgery.

2581011) SSNB at the suprascapular notch was performed using an unguided method

58) or under the guidance of electrophysiology,

24) fluoroscopy,

25) ultrasonography,

12) or computed tomography (CT)

26) in previous studies. Unguided or CT-guided SSNB injections into the shoulder showed a relatively low accuracy of 10% to 50%.

2627) Recently, Ko et al.

24) reported that there were no outstanding differences between the ultrasonographically guided SSNB and electrophysiologically guided SSNB in a randomized controlled trial.

In a report of Taskaynatan et al.,

28) the accuracy of ultrasound-guided SSNB assessed with neurostimulation was considered successful in 5 and semi-successful in 19 of 27 patients. Ultrasonographically guided SSNB and ANB that have the merit of being radiation-free real-time procedures have been used in recent studies, which verified the local anesthetic was infiltrated around the suprascapular notch, the suprascapular artery and nerve, and the posterior circumflex humeral artery.

121329) Gorthi et al.

12) reported ultrasonographically guided SSNB resulted in better shoulder scores than unguided SSNB at 1-month follow-up, and the latter method resulted in 2 cases of arterial puncture and 3 cases of direct nerve injury with neurologic deficit for 2 postoperative months.

SSNB for postoperative pain relief in arthroscopic shoulder surgery is a new modality.

30) Lee et al.

11) reported that arthroscopically assisted continuous SSNB was highly effective in controlling postoperative pain after shoulder surgery. According to our current study, SSNB performed under arthroscopic guidance was also very effective in controlling postoperative shoulder pain in patients with repaired rotator cuff tears.

ANB is a recently introduced advanced method for shoulder pain control.

25829) Lee et al.

11) reported that ultrasonographically guided ANB combined with SSNB in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair showed an improvement in VAS in the first 24 hours after surgery compared with SSNB alone. In the study,

11) the combination of SSNB and ANB tended to reduce rebound shoulder pain compared with SSNB alone.

Jeske et al.

10) described that SSNB with 10 mL of 1% ropivacaine had a duration of 24 to 48 hours. In our study, the duration of SSNB with 10 mL of 0.25% ropivacaine was 24 to 48 hours. The PCA was injected slowly at a low fixed dose: continuous dose, 0.5 mL/hr; total volume, 60 mL (fentanyl + necupam + NS + Nasea 0.6 mg); loading dose, 0.5 mL; and lockout time, 15 min to eradicate any bias derived from PCA. However, the patient could control the routine PCA in another article. Although in the study by Lee et al.

11) using a routine PCA, 12 patients had nausea and 3 patients had vomiting among 75 patients, there were only 3 patients with tolerable nausea, which was the reason why we used the low fixed dose of PCA.

Our study had a few weaknesses. First, the scoring methods used, such as VAS for pain, KSS, UCLA, and ASES, were subjective. However, all previous papers on regional block for postoperative pain control employed subjective scores; therefore, we considered VAS score as a dependable parameter of pain in the postoperative period after shoulder arthroscopy. Second, we administered PCA intravenously and intraarticular injection of triamcinolone 20 mg in patients with severe synovial hypertrophy in the rotator interval and axillary pouch of the shoulder. However, the intravenous PCA and intraarticular triamcinolone injection were carried out at a constant low dose to decrease the potential for bias that can distort the outcomes. The rebound pain phenomenon that can influence postoperative pain of the shoulder arthroscopy decreased when intraarticular triamcinolone injection was implemented. The strength of this study was as follows: group 1 and group 2 were not statistically significantly different in terms of demographics (p = 0.076) and KSS (p = 0.064), UCLA (p = 0.067), and ASES scores (p = 0.069); therefore, the influence of baseline characteristics on the results could be minimized. In addition, all the procedures of regional block and arthroscopy were implemented by one senior orthopedic surgeon who specialized in shoulder and sports medicine, which contributed to reducing the possibility of bias; however, further studies are warranted to determine whether our results can be reproduced in other hospitals.

In conclusions, arthroscopically guided SSNB and preemptive blinded SSNB and axillary nerve block in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair for medium-sized rotator cuff tears was more effective in improving VAS for pain in the first 48 hours after operation than blinded SSNB.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download