Abstract

This case demonstrates a rarely reported bilateral scapulohumeral bony ankylosis. A young woman developed extensive heterotopic ossifications (HOs) in both shoulder joints after being mechanically ventilated for several months at the intensive care unit in a comatose status. She presented with a severe movement restriction of both shoulder joints. Surgical resection of the bony bridges was performed in 2 separate sessions with a significant improvement of shoulder function afterwards. No postoperative complications, pain, or recurrence of HOs were noted at 1-year follow-up. Mechanical ventilation, immobilization, neuromuscular blockage, and prolonged sedation are known risk factors for the development of HOs in the shoulder joints. Relatively early surgical resection of the HOs can be performed safely in contrary to earlier belief. Afterwards, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or radiation therapy can be possible treatment modalities to prevent recurrence of HOs.

In literature, several terms are used to describe the formation of ossifications around joints, e.g., ectopic calcification, myositis ossificans, and periarticular ossifications. In the current medical literature, the term "heterotopic ossifications" is mostly used; however, no consensus regarding the definition has been made. Most authors define it as "formation of lamellar bone inside soft-tissue structures where bone normally does not exist."

Heterotopic ossifications (HOs) were first described by Patin in 1692 in children with myositis ossificans progressiva and Ceillier and Dejerine first noted and treated ossifications around joints in paraplegic soldiers during the first world war.

HOs might develop in several conditions. Three subtypes of HOs are described: traumatic, genetic, and neurogenic. Traumatic HOs occur in response to injuries or an operative intervention. Fractures of the acetabulum or (dislocation) fractures of the elbow joint treated with open reposition internal fixation are known for the development of HOs. Burns that limit joints, in particular the elbow joint, are also a traumatic event known for the development of HOs. And finally, HOs are frequently seen after implantation of a hip or elbow prosthesis.1)

Genetic HOs occur in patients with rare inherited diseases like fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva or progressive osseous heteroplasia, with multiple HOs developing throughout the body. The formation of neurogenic HOs occurs in response to injury to the central nervous system (CNS) with an incidence of 10%–20% in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) and 20% in spinal cord injured (SCI)-patients.2) Infrequently, HOs appear after admission at intensive care unit (ICU) in pancreatitis, Guillain-Barre, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).3)

We present a unique case of heterotopic ossifications in both shoulder joints of a young female who survived metastasized choriocarcinoma complicated with an ARDS, for which she required prolonged mechanical ventilation at ICU. The surgical method is discussed and a review of literature concerning the etiology and preventive measures is done.

A 40-year-old woman presented with a painless movement restriction of both shoulder joints, complicating activities in daily life such as personal hygiene and lifting her child.

One year ago, 5 days postpartum, respiratory insufficiency developed. She was admitted to the ICU and diagnosed with metastasized choriocarcinoma (lungs, liver, and kidney). Curative chemotherapy was started. She developed ARDS, further complicated by multiple organ failure, critical illness polyneuropathy, and bowel perforations, necessitating mechanical ventilation, alternating prone, and supine positions for several months for a better ventilation of the lungs. After 3 months, she was discharged and rehabilitation was initiated.

On examination, there was a global atrophy of shoulder musculature, with a fixed position of both shoulders at 20° of abduction and 45° of internal rotation. Shoulder movement was exclusively scapulothoracic. Active abduction was 60° bilaterally, and anteflexion was 45° in the right shoulder and 90° in the left shoulder (Fig. 1). No neurovascular deficits were present.

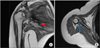

X-rays of both shoulder joints showed an identical osseous mass between the humerus and scapula (Fig. 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 3) and three-dimensional reconstruction computed tomography images (Fig. 4) showed complete bony bridges, located in the teres minor muscles. Also, isolated ossifications in the subscapularis muscles and avascular necrosis (AVN) of both humeral heads were demonstrated. The AVN of the humeral heads was thought to be a consequence of the corticosteroid therapy at the ICU or, less likely, changes in vascularization due to compression or traction by the bony bridges.

Surgical resections of the osseous bridges via posterior approaches in 2 separate sessions were planned, starting with the left, nondominant side (Fig. 4). Five months later, her right shoulder was operated in the same manner.

A posterior vertical incision was made from the posterolateral edge of the acromion in the direction of the axilla. After dissecting the subcutis and fascia, the posterior part of the deltoid muscle was mobilized. A large ossification appeared, which coursed the route of the teres minor muscle. A release of the triceps muscle was performed to gain full insight into the ossification. The native scapula was identified and dissection continued to the posterior side of the humerus, craniolateral to the axillary foramen. The bony bridge between the humerus and scapula was completely freed. A vertical osteotomy was performed along the lateral margin of the scapula, using an osteotome. The radial nerve coursed flush behind the ossification and was carefully protected while removing the bone, sometimes necessitating the use of a punch (Fig. 5). Nearly complete resection of the bony bridge was achieved without nerve damage, which improved the abduction immediately in contrast to rotation, which showed no improvement. The absence of rotation was thought to result from a frozen shoulder, since the ossification of the subscapularis muscle did not connect with surrounding bones, as seen on the MRI. After gentle manipulation, full rotation could be achieved. The shoulder joint was infiltrated with a corticosteroid and a local anesthetic, and the deep and superficial layers were closed with soluble sutures. Postoperative treatment was functional without any movement restrictions, guided by pain and under the supervision of a physiotherapist. We prescribed a 2-week course of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID; diclofenac 2dd 75 mg) to prevent recurrence of heterotopic ossifications.

At follow-up visits, the patient demonstrated a significant improvement of shoulder function with 160° of abduction bilaterally, of which 90° glenohumeral motion, 90° of internal rotation and 10° of external rotation. She was able to take care of her hygiene and lift her child again (Fig. 6). Strength of the rotator cuff was graded 5/5 when evaluated with the Medical Research Council Scale, and no postoperative complications, pain, or recurrence of HOs were noted on 1-year follow-up X-rays (Fig. 7). The AVN of the humeral heads was managed conservatively due to lack of symptoms.

The pathophysiology of the formation of HOs remains unclear and seems to be multifactorial. A traumatic event, genetic predisposition, and inflammatory factors are proposed as causal factors. According to Chalmers et al.,4) at least 3 criteria should be met to develop HOs: (1) the presence of osteoprogenitor cells; (2) inductive signal paths; and (3) a permissive environment which is favorable to osteogenesis. Although differences exist, these components closely mirror the critical components of fracture healing.

If our case is to be categorized in one of the subtypes, we think the neurogenic HOs appear to be the most appropriate category even though there was no direct damage to the CNS, since the ossifications seemed to have developed as a consequence of her comatose status.

The relationship between CNS and bone is not completely understood but what is clear is that specific neurotransmitters have a direct effect on bone metabolism by differentiating the progenitor cells, hereby upregulating the osteoblastic activity. It is for example known that long-bone fractures in TBI-patients have a two-fold faster union rate and up to 50% more callus formation. In TBI- and SCI-patients, two-thirds of the HOs develop in the hip, followed by formation of HOs around the knee and elbow joint. HOs of the shoulder joint after CNS-lesions are less frequently seen with an incidence described by Pansard et al.5) of 3.5%.

A comparable case is presented by An et al.6) A 38-year-old woman complained of a stiff right shoulder, caused by HO, 3 years after admission at ICU for 13 months in total following encephalitis. Her shoulder joint was severely limited in range of motion (ROM) and also adducted and internally rotated in neutral position. The authors believe that functional immobility seems to be an important factor in the pathogenesis. The specific functional restriction of the shoulder (internal rotation and adduction) described in the case leads us to believe that the posture of our patient during the immobilization period did play a significant role in the ankylosis of the joint.

Christakou et al.3) also reports immobilization as a potential risk factor, since it has been linked with disuse atrophy and a pro-inflammatory state which is a permissive environment to HO as described by Chalmers et al.4) and Christakou et al.3) additionally considers an important role for neuromuscular blockage in the occurrence of HOs as a pharmacological paralysis, which could parallel with damage to the CNS. Another factor associated to HO is mechanical ventilation. Patients who had been in mechanical ventilation for a longer period seem to be at a greater risk for the development of HOs. The pH-alterations as a consequence of respiratory alkalosis and acidosis change the calcium and phosphate salts precipitation which is thought to accelerate fracture union. Nauth et al.2) also confirmed that prolonged mechanical ventilation and coma contribute to an increased risk of HO-formation.

The role of physical therapy in patients with HOs remains controversial. There are those who believe that aggressive passive ROM exercises may lead to an increase of bone formation, because traumatic events may induce ossifications. In this context, Kir and Ozdemir7) described ossifications around shoulder joints in military recruits. They performed rifle drill exercises and developed ossifications around the contact area of the rifle.

It seems that immobilization seems to be an associated factor for the development of HOs, but too aggressive mobilization as well. Most authors therefore agree that 'gentle' physical therapy leads to better function and prevention of ankyloses.

According to Garland,8) resection of a HO in the shoulder joint is seldom necessary since ankylosis is uncommon. He found the HO in the shoulder joint invariably located inferomedial to the joint. Our case, however, presented with a complete bony bridge scapulohumeral, indeed inferomedial to the joint, but a more progressed and aggressive form of heterotopic ossification than those described by Garland.8) Furthermore, the ossification coursed the route of the teres minor muscle. In other joints, the most common and pathognomic location of heterotopic ossifications are mostly within the ligaments or capsular portions of the joint; e.g., in the elbow joint, the radial and ulnar collateral ligaments are the most common site of HO as well as the coronoid fossa.9)

In view of the high incidence of recurrence of the HOs, a delay in treatment was usually advised until the bony mass reaches radiological maturity and biological silence. Some authors believe that the alkaline phosphatase levels should normalize and the heterotopic bone should be quiescent on the bone scan.1) Recent literatures, however, suggest that early surgical excision with secondary prophylaxis (i.e., NSAIDs or radiation therapy [RT]) is safe. No need to wait for HO maturity, which confers several advantages such as easier surgery, more effective rehabilitation, and improved health of articular cartilage and surrounding bone. And overall, less recurrence of HOs is seen in patients with good neurological recovery and motor function.58)

Pansard et al.5) studied HOs in shoulder joints after CNS damage. In 16 of the 357 TBI-patients with HOs in multiple joints, the shoulder joints were affected. Ketoprofen was given for 10 days postoperatively. No RT was prescribed and no recurrence of HOs was reported.

NSAIDs and RT are both efficacious in the prevention of HO around hip prosthesis. The effect of NSAID therapy is based on a suppression of the prostaglandin system and therefore on the suppression of the inflammatory reaction that occurs postoperatively. Complications such as renal failure and gastrointestinal problems should be considered when prescribing these drugs. Postoperative radiation after hip replacements prevents conversion of precursor cells to bone-forming cells.10) To our knowledge, no study is reported that describes the effect of either radiation therapy or NSAIDs specifically on HOs in the shoulder joints. In the literature regarding hip implant related HOs (severe grade III/IV), those treated with RT are marginally more effectively prevented than with NSAIDs. On the contrary, several disadvantages of RT have also been described, such as wound healing problems, secundary malignancies, logistic problems, and costs.10)

In conclusion, we presented a rare case of bilateral scapulohumeral ankylosis. Crucial criteria of Chalmers et al.4) for the development of HOs were met and we identified immobilization, neuromuscular blockage, mechanical ventilation, and prolonged sedation as associated risk factors. We discussed the unique localisation and progressive nature of the bony bridges. Contrary to previous belief there was good evidence in favour of relatively early surgery, which was successful in this case. Recurrence of HO can be prevented by NSAIDs and/or RT; however, these are not feasible in all patients.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Preoperative range of motion of the arms. (A) Neutral position. (B) Maximal abduction. (C) Maximal anteflexion. |

| Fig. 3Magnetic resonance imaging showing avascular necrosis of the humeral head and isolated ossifications in the subscapularis muscle (red arrow) in the coronal plane (A) and a complete bony bridge located in the teres minor muscle (blue arrow) in the transverse plane (B). |

| Fig. 4Three-dimensional computed tomography reconstruction image showing isolated ossifications in the subscapularis muscle (red arrow) and the complete bony bridge in the teres minor muscle (blue arrow). |

| Fig. 5(A) Resection of the bony bridge via posterior approach with an osteotome. (B) Identification of the radial nerve in close proximity to the bony bridge (arrow). |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the patient and her family for giving permission to anonymously present this case.

References

1. Tsionos I, Leclercq C, Rochet JM. Heterotopic ossification of the elbow in patients with burns: results after early excision. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004; 86(3):396–403.

2. Nauth A, Giles E, Potter BK, et al. Heterotopic ossification in orthopaedic trauma. J Orthop Trauma. 2012; 26(12):684–688.

3. Christakou A, Alimatiri M, Kouvarakos A, et al. Heterotopic ossification in critical ill patients: a review. Int J Physiother Res. 2013; 1(4):188–195.

4. Chalmers J, Gray DH, Rush J. Observations on the induction of bone in soft tissues. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1975; 57(1):36–45.

5. Pansard E, Schnitzler A, Lautridou C, Judet T, Denormandie P, Genet F. Heterotopic ossification of the shoulder after central nervous system lesion: indications for surgery and results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013; 22(6):767–774.

6. An HS, Ebraheim N, Kim K, Jackson WT, Kane JT. Heterotopic ossification and pseudoarthrosis in the shoulder following encephalitis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987; (219):291–298.

7. Kir MC, Ozdemir MT. Myositis ossificans around shoulder following military training programme. Indian J Orthop. 2011; 45(6):573–575.

8. Garland DE. A clinical perspective on common forms of acquired heterotopic ossification. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991; (263):13–29.

9. Zeckey C, Hildebrand F, Frink M, Krettek C. Heterotopic ossifications following implant surgery: epidemiology, therapeutical approaches and current concepts. Semin Immunopathol. 2011; 33(3):273–286.

10. Sell S, Willms R, Jany R, et al. The suppression of heterotopic ossifications: radiation versus NSAID therapy: a prospective study. J Arthroplasty. 1998; 13(8):854–859.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download