Abstract

A 30-year-old male was involved in a car accident. Radiographs revealed a depressed marginal fracture of the medial tibial plateau and an avulsion fracture of the fibular head. Magnetic resonance imaging showed avulsion fracture of Gerdy's tubercle, injury to the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), posterior horn of the medial meniscus, and the attachments of the lateral collateral ligament and the biceps femoris tendon. The depressed fracture of the medial tibial plateau was elevated and stabilized using a cannulated screw and washer. The injured lateral and posterolateral corner (PLC) structures were repaired and augmented by PLC reconstruction. However, the avulsion fracture of Gerdy's tubercle was not fixed because it was minimally displaced and the torn PCL was also not repaired or reconstructed. We present a unique case of pure varus injury to the knee joint. This case contributes to our understanding of the mechanism of knee injury and provides insight regarding appropriate treatment plans for this type of injury.

Complex knee injuries are not common and the injury patterns vary; thus, management principles for the treatment of individual complex knee injuries have not been established.1) Complex knee injuries are usually the result of high-energy knee injuries caused by accidents or sport mishaps at all levels of competition. For any type of knee injury, an understanding of the mechanism of injury is important for detecting associated or occult lesions and for establishing an appropriate management plan.2,3) On the other hand, the imprint of the injury, as determined during radiographic examinations, can be utilized to reconstruct injury situations, for example, small bony lesions on a plain radiograph or bone contusions on magnetic resonance (MR) images often provide essential clues regarding the injured structures, for example, the presence of a Segond fracture in cases of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury,3,4) or the presence of the arcuate sign in cases of injury to the posterolateral corner (PLC) structures.5)

Here, we present a case of complex knee injury with a pure varus mechanism, which entailed a depressed marginal fracture of the medial tibial plateau by compression and avulsion fractures of Gerdy's tubercle and the fibular head, and tear of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) and the posterior horn of the medial meniscus. The mechanism of injury, its implications, the relevance of the associated lesions, and management principles are discussed.

A 30-year-old male was involved in a car accident. He was standing beside the door on the passenger side to guide parking, when unexpectedly, the car reversed quickly, and his left leg was trapped under the front passenger side wheel, which exerted a severe varus force on his left knee joint. He was immediately transported to the emergency room of our institute.

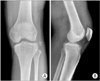

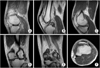

On admission, an immediate neurovascular examination excluded urgent medical problems and distal sensory, motor, and circulatory disturbances. Gross bruising and diffuse swelling were observed on the knee joint, especially on the lateral side, but no external wound was observed. The arc of motion and ligament integrity could not be checked due to severe pain and muscle guarding. Plain radiographs revealed a depressed marginal fracture of the medial tibial plateau and an avulsion fracture of the fibular head (Fig. 1). MR imaging confirmed the presence of these bony lesions. In addition, it revealed an avulsion fracture of Gerdy's tubercle, PCL rupture, and tear of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus, attachments of the lateral collateral ligament (LCL), and the biceps femoris tendon attached onto the avulsed fibular head (Fig. 2). Overall, a compressive lesion was present in the medial compartment and avulsive lesions were present in the lateral compartment.

Surgery was performed at 10 days after injury. An examination under anesthesia revealed severe instability of the knee, which included grade 3 posterior instability at 90° and 20° of knee flexion, grade 3 varus instability at 0° and 30° of knee flexion, and severe posterolateral rotatory instability. Through a medial longitudinal incision, the depressed marginal fracture of the medial tibial plateau was exposed, elevated, and the metaphyseal defect was filled with a bone graft, and then stabilized with a cannulated screw and washer. In addition, the semitendinosus tendon was harvested using a closed-end graft harvester for PLC reconstruction. PLC structures were exposed using a lateral curvilinear incision. Grossly, the LCL and biceps femoris tendon were totally avulsed from the fibular attachment with comminuted small bone fragments and rupture of the posterolateral capsule. Briefly, the peroneal nerve was first identified and protected. From the anterior surface of the remaining fibular head, a guide pin for a fibular tunnel was passed aiming at the posterior and inferior surfaces of the fibular head, and then, a 6-mm diameter tunnel was made using a cannulated reamer and the prepared semitendinosus tendon was passed through the tunnel. As the avulsed fibular head was comminuted, direct repair or fixation of the avulsed structures was not feasible. Thus, the LCL and biceps femoris tendon were secured by placing whipstitches with 1-0 nonabsorbable sutures, which were then passed through the fibular tunnel, and the structures were reduced at their origins and stabilized by tying the sutures. To obtain better stabilization, the tissues on the avulsed fragments and the LCL and biceps tendon were sutured to soft tissues of the fibular head, and then a 4.0 mm cannulated buttress screw was used for fixation from just above the largest fragment to the tibia. Finally, we completed the augmented reconstruction of the LCL and popliteofibular ligament component of the PLC using a figure-of-8 fibular sling method as follows: a Steinmann pin was first fixed between the LCL femoral attachment and the popliteus tendon attachment, and the semitendinosus tendon graft was wrapped around the Steinmann pin to check isometry. During knee motion, from full extension to 110° of knee flexion, we confirmed that the graft excursion did not exceed 2 mm. After confirming optimal isometry, the tendon limb from the anterior portion of the fibular tunnel was placed just posterior to the tested point, while the limb from the posterior portion of the tunnel was placed just anterior to the tested point. The limbs were then fixed using a spiked washer and screw technique with the knee held in 20° of flexion and neutral rotation (Figs. 3 and 4).

The fracture of Gerdy's tubercle was not fixed because it was minimally displaced. We also did not repair or reconstruct the PCL, because after repair and augmented reconstruction of PLC structures, we confirmed complete stabilization of the knee in full extension to 60° of flexion without any posterior subluxation of the tibia, and we also expected healing of the PCL during the immobilization period. After surgery, the knee was placed in an immobilizer in full extension for 4 weeks, during which weight bearing was not allowed. From 5 weeks after surgery, partial weight bearing with a crutch was allowed, and full weight bearing was started from 12 weeks after surgery. Isometric quadriceps muscle exercises were started immediately and a range of motion program and closed kinetic chain exercises were also started from 5 weeks after surgery. At 2 years, the patient had achieved full range of knee motion (full extension to 140° of flexion) without subjective instability. He did not have posterolateral instability and grade 1 instability in the posterior drawer test even without PCL surgery, and he was able to participate in his previous sports activities (jogging, hiking, and golfing) without discomfort (Fig. 5).

Understanding the mechanism of knee injury is important because it allows detection of associated and occult lesions,, and it helps knee surgeons to establish appropriate management plans to treat the injuries present,2,3) guides rehabilitation protocols, provides an indication of the ultimate outcome, and helps in developing an injury prevention strategy. The major forces acting on the knee joint include translation (anterior or posterior), angulation (varus and valgus), rotation (internal and external), hyperextension, axial loading, and direct blow. Most knee injuries occur as a result of a combination of two or more of these forces.2,3) In previous studies of a mechanism-based pattern approach using MR images, pure varus injury was reported very rarely as varus forces are usually accompanied by rotation.3,4) These studies did not mention combined PCL injury caused by this type of injury mechanism3,4) and no other study in the literature has reported pure varus injury. The current case report provides useful information regarding the resultant lesions caused by a pure varus knee injury mechanism, and helps understand the fundamental anatomical characteristics of the medial and lateral compartments of the knee joint.

The depressed marginal fracture of the medial tibial plateau observed in our case deserves attention. Marginal fractures of the medial tibial plateau have been attributed to different location-dependent mechanisms. For example, lesions in the anterior portion have been attributed to hyperextension with hyperextension in varus,6) while those in the posterior portion were attributed to avulsion of the semimembranosus tendon7) or to a compression fracture (Fig. 6).8) Mid-marginal fractures of the medial tibial plateau can differentiate between an avulsion and compression induced injuries. Previously, the lesions in the mid-portion of the medial plateau margin were described as 'reverse Segond fractures', which often accompany rupture of the PCL and the posterior horn of the medial meniscus.2,9) These lesions result from avulsion of the deep medial collateral ligament by flexion, varus, and internal rotation.9) However, the medial marginal fracture in the described case differs from previously described 'reverse Segond fractures' even with combined injury of the PCL and the posterior portion of the medial meniscus, because the fracture was caused by compression rather than by avulsion. The tensile avulsion fracture in the lateral compartment in our case also deserves attention. Anteriorly, Gerdy's tubercle can be avulsed by the iliotibial band. Avulsion fractures of Gerdy's tubercle can occur due to small avulsions, as in the present case, or due to large avulsions involving the plateau fracture.2) Segond fractures occur at the mid-lateral margin of the lateral tibial plateau as a result of avulsion of the anterior oblique band of the LCL due to excessive flexion, varus, and external rotation.3) Posteriorly, avulsion fractures of the fibular head can be caused by small avulsions of the styloid process, or by avulsion of the arcuate complex (the 'arcuate sign'), or by a large avulsion of the conjoined tendons of the LCL and biceps femoris.5) On the other hand, comminuted fracture of the fibular head also occurs during compressive failure resulting in a high-energy plateau fracture. The described case showed a small avulsion of Gerdy's tubercle and a large avulsion of the fibular head, which is compatible with the exertion of a pure varus force on the entire lateral compartment (Fig. 7).

No consensus has been achieved regarding the principle for managing complex knee ligament injuries. Regarding early vs. delayed reconstruction, previous studies found that early repair or reconstruction of acute complex knee ligament injuries seems to provide a more favorable outcome than delayed reconstruction.10) Regarding repair vs. reconstruction, particularly for acute PLC injuries, recent studies have demonstrated that repair alone of PLC structures results in significantly higher failure than early reconstruction, which suggests that early reconstruction of the PLC is a more reliable option than repair alone for acute PLC injuries.1) In the described case, we performed primary repair and augmented reconstruction of the PLC structures during the acute stage, and obtained an excellent short-term outcome. We believe that early repair of all available PLC structures, particularly when there is combined injury to the biceps tendon and/or popliteus tendon, and simultaneous augmented reconstruction of the key PLC ligament structures is a better option than repair alone or reconstruction alone for this type of injury.

In the described case, we did not perform repair or reconstruction for the combined PCL injury. After completing surgery for the PLC structures, we found that the knee was completely stable from full extension to 60° of flexion without any posterior subluxation of the tibia. Accordingly, we did not perform early surgery for the injured PCL in view of its healing capacity and our intention of performing delayed reconstruction if the patient had high-grade posterior instability. As was expected, the patient had only mild posterior instability even without surgery for PCL at 6 months after surgery. Nevertheless, a longer follow-up is required before we can confidently state that our strategy is justified.

We presented a case of pure varus knee injury, which resulted in a compressive depressed marginal fracture of the mid-medial tibial plateau and avulsion fractures of Gerdy's tubercle and the fibular head and tear of the PCL and posterior horn of the medial meniscus. We believe that this case contributes to our understanding of varus type knee injury and related pathologies, and demonstrates the importance of devising appropriate treatment plans.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) plain radiographs showing a mid-marginal fracture of the medial tibial plateau and an avulsion fracture of the fibular head. |

| Fig. 2Sagittal (A-C), coronal (D, E), and axial (F) magnetic resonance imaging scans (proton density; repetition time = 3,900 msec, echo time = 15 msec). (A) An undisplaced, minimal avulsion fracture was clearly seen. (B) Although the anterior cruciate ligament maintained its integrity, the posterior cruciate ligament was torn, whereas the lateral meniscus was intact (A). (C) The posterior horn of the medial meniscus was torn. (D) A compressive mid-marginal fracture of the medial tibial plateau was also present. The avulsed fibular head had attachments to the lateral collateral ligament (D) and the biceps femoris tendon (E). (F) Marginal fracture of the medial plateau and avulsion fracture of Gerdy's tubercle were obvious on the axial image of the tibial plateau. |

| Fig. 3Surgical treatment for posterolateral corner (PLC) injury in the current case. (A) The PCL was exposed by a longitudinal curvilinear incision and the peroneal nerve was identified and protected. (B) The avulsed lateral collateral ligament and biceps tendon were secured using whipstitches, which were then passed through the fibular tunnel for PLC reconstruction, and the structures were reduced at their origins and stabilized by tying the sutures. (C) Finally, we completed the augmented reconstruction of the lateral collateral ligament and popliteofibular ligament component of the PLC using a figure of 8-fibular sling method. |

| Fig. 4Postoperative anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs showing reduction of the marginal fracture of the medial tibial plateau and the avulsed fibular head and adequate reconstruction of posterolateral structures. |

| Fig. 5Postoperative 2-year anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs showing bony union of medial tibial plateau and minimal osteoarthritic change. |

| Fig. 6Schematic illustration of the compressive marginal lesion of the medial tibial plateau (I, II, III) and avulsive marginal lesions of the lateral tibial plateau (IV, V, VI, VII). I: at the anterior portion by hyperextension varus, II: at the mid-medial portion by pure varus, III: at the posterior portion, which could have occurred via compression or avulsion mechanism by the semitendinosus, VI: avulsion of Gerdy's tubercle by the iliotibial band, V: Segond fracture cause by avulsion fracture of the lateral capsular ligament or anteroinferior band of the lateral collateral ligament, VI: avulsion of the anteroinferior portion of the fibular head by the conjoined tendon of the lateral collateral ligament and biceps femoris tendon, VII: avulsion of the styloid process of the fibular head by the arcuate complex. |

References

1. Levy BA, Dajani KA, Morgan JA, Shah JP, Dahm DL, Stuart MJ. Repair versus reconstruction of the fibular collateral ligament and posterolateral corner in the multiligament-injured knee. Am J Sports Med. 2010; 38(4):804–809.

2. Gottsegen CJ, Eyer BA, White EA, Learch TJ, Forrester D. Avulsion fractures of the knee: imaging findings and clinical significance. Radiographics. 2008; 28(6):1755–1770.

3. Hayes CW, Brigido MK, Jamadar DA, Propeck T. Mechanism-based pattern approach to classification of complex injuries of the knee depicted at MR imaging. Radiographics. 2000; 20 Spec No:suppl 1. S121–S134.

4. Hayes CW, Coggins CA. Sports-related injuries of the knee: an approach to MRI interpretation. Clin Sports Med. 2006; 25(4):659–679.

5. Lee J, Papakonstantinou O, Brookenthal KR, Trudell D, Resnick DL. Arcuate sign of posterolateral knee injuries: anatomic, radiographic, and MR imaging data related to patterns of injury. Skeletal Radiol. 2003; 32(11):619–627.

6. Yoo JH, Kim EH, Yim SJ, Lee BI. A case of compression fracture of medial tibial plateau and medial femoral condyle combined with posterior cruciate ligament and posterolateral corner injury. Knee. 2009; 16(1):83–86.

7. Chan KK, Resnick D, Goodwin D, Seeger LL. Posteromedial tibial plateau injury including avulsion fracture of the semimembranous tendon insertion site: ancillary sign of anterior cruciate ligament tear at MR imaging. Radiology. 1999; 211(3):754–758.

8. Vanek J. Posteromedial fracture of the tibial plateau is not an avulsion injury: a case report and experimental study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994; 76(2):290–292.

9. Engelsohn E, Umans H, Difelice GS. Marginal fractures of the medial tibial plateau: possible association with medial meniscal root tear. Skeletal Radiol. 2007; 36(1):73–76.

10. Chhabra A, Cha PS, Rihn JA, et al. Surgical management of knee dislocations: surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005; 87:Suppl 1. (Pt 1):1–21.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download