Abstract

Partial or complete absence of the posterior arch of the atlas is a well-documented anomaly but a relatively rare condition. This condition is usually asymptomatic so most are diagnosed incidentally. There have been a few documented cases of congenital defects of the posterior arch of the atlas combined with atlantoaxial subluxation. We report a very rare case of congenital anomaly of the atlas combined with atlantoaxial subluxation, that can be misdiagnosed as posterior arch fracture.

Congenital defect of the posterior arch of the atlas is an uncommon condition but its characteristics have been well described. Geipel1) reported that clefts of the posterior arch occurred in 4% of 1,613 autopsies. These anomalies are considered by some to be benign. Almost all cases have been discovered incidentally.2) However, when evaluating an acute neck trauma, it is important to be aware of these cervical congenital anomalies because of the possibility of misdiagnosing them as a fracture and/or dislocation. In this report we will discuss a very rare case of congenital anomaly of the atlas which could have been mistaken as a posterior arch fracture of the atlas combined with atlantoaxial subluxation after a traffic accident.

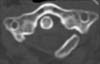

A 28-year-old woman was referred to the emergency department with left hip pain, wrist pain and neck pain after being involved in a traffic accident. On physical examination, her neurologic system showed no abnormal findings. Roentgenographic studies showed left acetabular fracture and left distal radius fracture. A lateral cervical radiograph taken initially in the investigations suggested posterior arch fracture (Fig. 1). A trans-oral anterior-posterior view of the atlas revealed an atlantoaxial subluxation (AAS) (Fig. 2). Computed tomography (CT) images with three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction demonstrated the absence of the posterior arch and the presence of a persistent posterior tubercle. Like the cervical radiograph, there were signs of AAS in the CT images (Figs. 3 and 4). Magnetic resonance images (MRI) showed no definite evidence of rupture of the alar or transverse ligament or soft tissue swelling (Fig. 5).

No evidence of traumatic injury was shown on whole body bone scinitigraphy (Fig. 6). The patient's neck pain resolved spontaneously. Post-recovery flexion and extension films revealed the absence of the posterior arch of the atlas but there was no evidence of atlantoaxial instability (Fig. 7). The patient was asymptomatic at a follow-up visit six months after the accident.

There are three ossification centers of the atlas: the anterior ossification center, that forms the anterior tubercle, and two lateral centers, from which the lateral masses and the posterior arch form.2) In 2% of the population, a fourth center forms the posterior tubercle. By the seventh gestational week, the lateral centers have extended dorsally to form the posterior arch. At birth, the posterior arches are nearly fused except for several millimeters of cartilage, and union occurs between the ages of 3 and 10 years.3) The anterior center unites with the lateral centers at 5 to 9 years of age. Defects of the posterior arch are assumed to occur because of a failure of local chondrogenesis rather than subsequent ossification.1,2)

Currarino et al.4) described an anatomical classification of posterior arch defects of the atlas (Table 1). The type A anomaly is the most frequent form (> 95%), and fusion defects of C1 hemiarches can affect 3% to 5% of the population.5) Our patient was found to have a type C defect.

Patients are most commonly asymptomatic, though the defect can cause chronic cervical pain, headache, and Lhermitte sign.6) Cervical myelopathy is also possible and has been reported in several cases,6,7) especially with types C and D of the Currarino classification, which are both associated with the presence of a posterior osseous fragment.

Diagnosis is usually made as a casual finding in asymptomatic patients. In other cases, the defect is observed after lateral cervical radiography after a minor accident8) where the defect can be mistaken for a cervical fracture. On imaging, fractures demonstrate irregular edges with associated soft tissue swelling, while the congenital clefts are smooth with an intact cortical wall and have an absence of soft tissue swelling.9) Magnetic resonance imaging is reserved for cases where any neurologic abnormality is observed or there is a suspicion of myelopathy.

Treatment is normally conservative; surgery is indicated when patients present atlanto-axis instability and spinal cord compromise.7) Some authors, however, recommend early surgical intervention in patients with types C and D (with posterior osseous fragment) to avoid accumulative spinal injury.6) Another reason is that type C and D are likely to cause transient quadriparesis after minor trauma including even inappropriate positioning of the head and neck.

Only two cases of cervical instability associated with these congenital anomalies have been reported. Park et al.9) reported a 57-year-old man who had bipartite atlas discovered during an ophthalmologic evaluation. A transoral anterior-posterior view of the atlas revealed an AAS. The patient did not undergo any treatment because he had minimal symptoms. Schulze and Buurman10) described a 48-year-old female who had complete absence of the posterior arch of the atlas discovered during a metastatic survey. Flexion and extension films revealed a moderate amount of atlantoaxial instability, as evidenced by an increase in the atlantodental interspace. The patient was asymptomatic, and did not undergo any treatment.

In this case, the authors initially suspected both a traumatic event and a congenital anomaly as the cause of the atlantoaxial subluxation. Because cases of atlantoaxial subluxation due to trauma can be fatal, immediate surgical intervention is sometimes needed. Further investigation is essential for improving the accuracy of diagnosis. CT, MRI or other scans are usually needed.

In spite of the low incidence of congenital anomaly of the atlas, surgeons must keep the possibility of its existence in mind when suspecting traumatic atlantoaxial subluxation in a patient.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 3

Axial computed tomography at the level of C1 showing absent posterior arch of the atlas and atlantoaxial subluxation.

Fig. 5

T2-weighted magnetic resonance images showing no definite evidence of rupture of alar or transverse ligament and soft tissue swelling.

Fig. 7

Flexion and extension radiographs showing absence of the posterior arch of the atlas without evidence of atlatoaxial instability (arrow).

Table 1

Classification of the Congenital Anomalies of the Posterior Arch of the Atlas according to Currarino et al.4)

References

1. Geipel P. Zur kenntnis der Spina bifida des Atlas. Forstschr Rontgenstr. 1930; 42:583–589.

2. Logan WW, Stuard ID. Absent posterior arch of the atlas. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1973; 118(2):431–434.

3. Connor SE, Chandler C, Robinson S, Jarosz JM. Congenital midline cleft of the posterior arch of atlas: a rare cause of symptomatic cervical canal stenosis. Eur Radiol. 2001; 11(9):1766–1769.

4. Currarino G, Rollins N, Diehl JT. Congenital defects of the posterior arch of the atlas: a report of seven cases including an affected mother and son. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994; 15(2):249–254.

5. Phan N, Marras C, Midha R, Rowed D. Cervical myelopathy caused by hypoplasia of the atlas: two case reports and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1998; 43(3):629–633.

6. Sagiuchi T, Tachibana S, Sato K, et al. Lhermitte sign during yawning associated with congenital partial aplasia of the posterior arch of the atlas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006; 27(2):258–260.

7. Klimo P Jr, Blumenthal DT, Couldwell WT. Congenital partial aplasia of the posterior arch of the atlas causing myelopathy: case report and review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003; 28(12):E224–E228.

8. O'Sullivan AW, McManus F. Occult congenital anomaly of the atlas presenting in the setting of acute trauma. Emerg Med J. 2004; 21(5):639–640.

9. Park SY, Kang DH, Lee CH, Hwang SH. Combined congenital anterior and posterior midline cleft of the atlas associated with asymptomatic lateral atlantoaxial subluxation. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2006; 40(1):44–46.

10. Schulze PJ, Buurman R. Absence of the posterior arch of the atlas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980; 134(1):178–180.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download