Abstract

During imaging studies or surgical procedures, anomalous forearm and wrist muscles are occasionally encountered. Among them, the flexor carpi radialis brevis is very rare. Because the trend is growing toward treating distal radius fractures with volar plating, the flexor carpi radialis brevis is worth knowing. Here, we report two cases with a review of the literature.

Various anatomical anomalies of musculotendinous structures around the wrist are known.1) They are often found by chance during imaging studies and surgical procedures, and sometimes perceived when they cause certain pathologic conditions, such as compression neuropathy.1,2) The flexor carpi radialis brevis (FCRB) is one of the rare anomalous muscles. As volar plating for distal radius fractures is becoming popularized, surgeons are more likely to meet the FCRB. Here, we report two cases of the FCRB with a review of the literature.

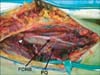

A 55-year-old woman presented with painful limitation of motion of her right wrist. She had fallen on the stairs the previous day. Clinical and radiographic evaluation revealed a comminuted distal radius fracture. It was planned to treat the fracture by open reduction and internal fixation with volar plating. The surgery proceeded as planned with endotracheal general anesthesia. The standard volar approach was performed. The surgical dissection began with identification of the flexor carpi radialis (FCR) tendon. After the tendon sheath was released, the FCR tendon was retracted, and the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) tendon was identified. Usually, the pronator quadratus (PQ) and the fracture can be seen through the interval between the FPL and the brachioradialis (BR). But in this case, there was an anomalous musculotendinous structure between the FPL and the BR (Fig. 1). The functions of the FPL and the anomalous muscle were checked by tensioning them, respectively. Tension on the anomalous muscle flexed the wrist without thumb motion. Based on the anatomic location and function of this anomalous muscle, it was thought to be the FCRB. Because the patient had consented only to the procedures related to the distal radius fracture, we did not perform further anatomical dissection beyond that required for internal fixation of the distal radius fracture. The flexor tendons and the median nerve were ulnarly swept, and the FCRB was retracted radially, to expose the PQ. The PQ was released from its radial insertion, and ulnarly reflected to expose the fracture; and then volar plate fixation was performed, as usual. Because the FCRB did not act as a hindrance to the volar plate fixation, additional procedure for the FCRB was not needed.

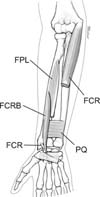

A 49-year-old woman injured her left forearm, while making up her room, when a box fell on her left forearm. Plan radiographs showed shaft fractures of the radius and ulna. She underwent open reduction and internal fixation under endotracheal general anesthesia. For the radius shaft fracture, the standard volar approach was used. As in case 1, the FCRB was found between the FPL and the BR (Fig. 2). Because the surgical approach was more proximal and longer, the origin of the FCRB was exposed. The FCRB originated from the volo-radial border of the radius between the radial insertion of the PQ and the origin of the FPL. It was distinct from the PQ and the FPL without connection. Distally, it ran superficial to the PQ, and radial to the FPL. The functions of the FCR, FPL, and FCRB were checked by tensioning them, respectively. After stripping the radial insertion of the PQ, the plate fixation was performed without difficulty. Because it was not within the scope of the surgery, we did not perform further dissection on the distal insertion of the FCRB.

The FCRB is a rare anomalous muscle of the wrist. From the 19th century, it has been described in several cadaveric dissection studies, especially in Japanese literature.3,4) It was first described by Fano in 1851, and the name of flexor carpi radialis brevis vel profundus was given by Woods in 1867.3) The incidence of the FCRB has been reported to be 2.6% to 7.5%.4) The FCRB originates from the lower one-third of the radius on its volar surface, or volo-radial border between the origin of the FPL and the insertion of the PQ, and it inserts into the base of the second or third metacarpal. But, its insertion is subject to frequent variations, and may be into any metacarpal base except the first or fifth, and radial side carpal bones, such as the scaphoid, trapezium, trapezoid, and capitate.3) The FCRB is innervated by the anterior interosseous nerve.1,3) While the FCR is superficial to the deep fascia in the same plane with the palmaris longus, the FCRB is located in the deep compartment, and occupies the space between the FPL and the BR, superficial to the PQ. The FCRB is composed of chubby fusiform muscle belly and relatively short tendon. The muscle belly of the FCRB is noticeable by its presence in the distal forearm, where tendinous and neurovascular structures are predominant. When it enters the hand, it passes the special osteofibrous tunnel of the FCR, which is separated from the carpal tunnel, and formed by the attachment of the flexor retinaculum to the two borders of the groove on the trapezium.2,5,6) Fig. 3 is an anatomical illustration showing the relationship between the FCRB, FPL, FCR, and PQ. The FCR may have origins from the tendon of biceps, lacertus fibrosus, brachialis, the coronoid process of the ulna, and the anterior oblique line of the radius.6) But, such a case is extremely rare; and even if it arises from the anterior oblique line of the radius, it should be superficial to the flexor digitorum superficialis.3) So, the FCRB can be distinguished from a split-off accessory head of the FCR. Unusual variations of the FCRB have been described. Dodds1) reported a case in which the FCRB originated from the distal radial metaphysis, occupying the position of the radial insertion of the PQ, and causing hypoplasia of the PQ. Nakahashi and Izumi4) described the FCRB that passed the wrist through the carpal tunnel, and interconnected to the extensor carpi radialis brevis between the bases of the second and third metacarpals.

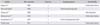

Recently, as volar plating of distal radius fractures is becoming popularized, surgeons have more likelihood of meeting the FCRB. In a review of the English literature, we found only ten clinical cases; and all the cases were reported after 2006.2,7,8,9,10) The published case reports, including our two cases, are summarized in Table 1. Among them, seven cases were related to the distal radius fracture.7,9) One case was discovered during surgical treatment of a wrist laceration,8) and the remaining two cases were presented as a painful swelling or mass caused by tenosynovitis of the FCRB.2,10) Anomalous muscles in the hand and wrist often arouse compression neuropathy. The FCRB may also cause anterior interosseous nerve compression.5) But because the compression site is far distal to its branches supplying the FPL and the flexor digitorum profundus, it rarely-if ever-evokes clinically significant symptom.1) Moreover, because the FCRB is usually located in the osteofibrous tunnel of the FCR, which is outside of the carpal tunnel, it is less likely to cause carpal tunnel syndrome.2) In contrast, the FCRB can cause tenosynovitis. In a case report of the FCRB that presented as a painful mass, Peers and Kaplan2) described extensive tendinosis and tenosynovitis of the FCRB and the FCR, and performed complete excision of the FCRB in its entirety. Kosiyatrakul et al.10) also reported a case of tenosynovitis of the FCRB. In any event, symptomatic FCRB is extremely rare. To our knowledge, there has been no case except the two cases mentioned above.2,10)

The clinical significance of the FCRB is its proximity to the standard volar approach for the distal radius fracture.7,9) As the trend toward treating distal radius fractures with volar plating is growing, it is important for surgeons to be aware of this anomalous muscle. In the author's experience, volar plate fixation of the distal radius has not been interrupted by the FCRB. Kang et al.7) and Mantovani et al.9) also mentioned that the presence of the FCRB neither required additional procedures, nor induced intraoperative or postoperative complications. But, even if a volar plate fixation will not be affected by the presence of the FCRB, knowledge about this anomalous muscle will be helpful to prevent surgeon's perplexity, when faced with this muscle. In that case, tensioning test of the suspected tendon is informative.

Mantovani et al.9) reported six cases of the FCRB in 172 distal radius fractures (3.5%). We performed volar plating for 71 cases of the distal radius fracture between 2008 and 2010. So, the incidence of the FCRB was 2.8%. As Mantovani et al.9) pointed out, further clinical reports and anatomical studies will be needed, to determine the exact incidence within the wider population.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1The wrist crease and hand are on the left side of the photograph. The flexor carpi radialis brevis (FCRB) runs between the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) and the brachioradialis. FCR: flexor carpi radialis. |

| Fig. 2The wrist crease and hand are on the right side of the photograph. The flexor carpi radialis brevis (FCRB) originates from the volo-radial border of the distal one-third of the radius, and runs superficial to the pronator quadratus (PQ). The fracture is marked with a white arrowhead. |

| Fig. 3Anatomical illustration of the flexor carpi radialis brevis (FCRB). The mid portion of the FCR is cut. The FCRB originates between the origin of the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) and the insertion of the pronator quadratus (PQ). The FCRB runs superficial to the PQ, and enters into the osteofibrous tunnel of the FCR. |

References

1. Dodds SD. A flexor carpi radialis brevis muscle with an anomalous origin on the distal radius. J Hand Surg Am. 2006; 31(9):1507–1510.

2. Peers SC, Kaplan FT. Flexor carpi radialis brevis muscle presenting as a painful forearm mass: case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2008; 33(10):1878–1881.

3. Carleton A. Flexor carpi radialis brevis vel profundus. J Anat. 1935; 69(Pt 2):292–293.

4. Nakahashi T, Izumi R. Anomalous interconnection between flexor and extensor carpi radialis brevis tendons. Anat Rec. 1987; 218(1):94–97.

5. Spinner M. Injuries to the major branches of peripheral nerves of the forearm. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders;1979. p. 192–193.

6. Tountas CP, Bergman RA. Anatomic variations of the upper extremity. New York: Churchill Livingstone;1993. p. 139–140.

7. Kang L, Carter T, Wolfe SW. The flexor carpi radialis brevis muscle: an anomalous flexor of the wrist and hand. A case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2006; 31(9):1511–1513.

8. Chong SJ, Al-Ani S, Pinto C, Peat B. Bilateral flexor carpi radialis brevis and unilateral flexor carpi ulnaris brevis muscle: case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2009; 34(10):1868–1871.

9. Mantovani G, Lino W Jr, Fukushima WY, Cho AB, Aita MA. Anomalous presentation of flexor carpi radialis brevis: a report of six cases. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2010; 35(3):234–235.

10. Kosiyatrakul A, Luenam S, Prachaporn S. Symptomatic flexor carpi radialis brevis: case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2010; 35(4):633–635.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download