Abstract

Nodular fasciitis is a benign, reactive myofibroblastic tumor that is often mistaken for a sarcoma because of its histological appearance and rapid growth. Involvement of a finger is extremely rare. We report a case of nodular fasciitis of the thumb, accompanied by bone erosion. Magnetic resonance findings suggested the possibility of a malignancy, which could have led to misdiagnosis as a malignant soft tissue sarcoma. Instead, the lesion was treated by excisional biopsy, which confirmed nodular fasciitis. There has been no evidence of local recurrence at recent follow-up, 1 year after surgery. This case illustrates that, to avoid unnecessarily aggressive surgery, nodular fasciitis must be included in the differential diagnosis for any finger lesion that resembles a sarcoma, even if bone erosion is present.

Nodular fasciitis is a benign, reactive, subcutaneous fibroblastic tumor that may be mistaken for a sarcoma because of its rapid growth and aggressive histological appearance.1-3) This lesion is most often found in the forearm, and involvement of the thumb is extremely rare.4) We present a case of nodular fasciitis producing erosion of the cortical surface in the proximal phalanx of the thumb.

A 30-year-old, right-hand dominant woman was presented with a rapidly growing mass of the right thumb, without any history of trauma. She had first noticed a small mass in the dorsoradial aspect of the right thumb approximately one month ago. There was no generalized fever or local inflammatory signs. Her medical and family histories were unremarkable. On physical examination, a 2 × 2 cm sized solid nontender mass was present on the radial side of the proximal phalanx of her right thumb. There was no local heating, redness, or discharge (Fig. 1). Range of motions of the thumb and the neurovascular status were normal.

Radiographs of the right thumb showed a well-marginated cortical erosion of the radial aspect of the proximal phalanx with soft tissue swelling (Fig. 2). On magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, the well-defined mass measured 1.4 × 2.3 × 1.5 cm, and isointense on T1-weighted images and heterogeneously high signal intensity on T2-weighted images (Fig. 3). After a gadolinium contrast injection, the lesion presented diffuse enhancement, but some areas were not enhancement (Fig. 4). Although the lesion was not aggressive in radiologic studies and the size of the mass was less than 3 cm, we performed an incisional biopsy of the mass to rule out a sarcoma.

At operation, the well-circumscribed, pear-shaped mass had compressed the digital neurovascular bundle and had eroded the radial side of the proximal phalanx. The soft tissue mass was easily isolated from the surrounding soft tissues. Next, we performed a complete excision of the mass. The intraoperative biopsy was not suspicious malignancy.

On histopathological examination, the specimen showed a well-circumscribed lesion alternating abundant spindle cells admixed with hyalinized hypocellular areas. The high-power view showed plump, randomly orientated spindle cells surrounded by myxoid stroma. Although cellularity of the lesion was high, hyperchromatism and variations in the size and shape of the nuclei were mild. Mitotic activity ranged from 5 to 10 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields, with no atypical forms identified (Fig. 5). In immunohistochemical studies, the spindle cells were positive for vimentin and alpha-smooth muscle actin (Fig. 6). At the recent one-year follow-up after surgery, there was no evidence of local recurrence or of distant metastasis.

Nodular fasciitis was first described by Konwaler et al.5) in 1955. It is a benign proliferation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Its pathogenesis is unclear, but it may be triggered by trauma or a local inflammatory process. Nodular fasciitis is a self-limiting reactive process, not a true neoplasm.1,6) It most often occurs in young adults, between 20 to 40 years of age, and rarely in old adults over 60 years of age.1) It typically involves the upper extremity (48%), trunk (20%), head and neck (17%), and the lower extremity (15%).2,6) Nodular fasciitis is rare in the hands and feet, and very rare in the fingers.1-3) Clinically, nodular fasciitis is characterized by rapid growth, and sometimes accompanied by pain and tenderness. The lesions appear as solitary, well-circumscribed, round to oval, superficial small nodules less than 2 cm in diameter.1) Nearly all nodules have been effectively treated by local excision. Recurrence is rare and occurs in 1-2% of all patients.3)

MR features of nodular fasciitis are nonspecific. The lesions of nodular fasciitis appears as well-defined, round to oval masses. Histological variability in tissue composition and cellularity may account for varying MR features.2,4) Histologically, younger nodular fasciitis lesions of fibroblastic proliferation is associated with a myxoid matrix rich in acid mucopolysaccharide.7) Older lesions tend to present a more fibrous histology. In this regard, nodular fasciitis can be subdivided into three lesions: myxoid (type 1), cellular (type 2), and fibrous (type 3). Myxoid and cellular lesions are iso- to hyperintense to skeletal muscle on T1 weighted images and iso- to hyperintense to fat on T2 weighted images. Fibrous lesions are markedly hypointense on T1 and T2 images.7) Following a gadolinium injection, nodular fasciitis usually shows diffuse or peripheral enhancement. Differential diagnoses on MR images include glomus tumor and neurogenic tumor. Since these tumors usually show nonspecific MR imaging features, a surgical biopsy is needed to obtain proper diagnosis.

Microscopically, nodular fasciitis consists predominantly of plump, immature fibroblasts that are arranged in short irregular bundles and fascicles, accompanied by a dense reticulin meshwork with small amounts of mature collagen. Although mitotic figures are fairly common, atypical mitosis is virtually never seen.1,6) A chief diagnostic criterion is the abundance of ground substance, which gives a loosely textured feathery pattern, similar to the appearance of a tissue culture.6) Immunohistochemical stains for desmin, cytokeratin, and S-100 are typically negative in nodular fasciitis.2,3)

Nodular fasciitis in the hand needs to be distinguished from other tumorous lesions. A giant cell tumor of tendon sheath can be differentiated from nodular fasciitis clinically by a slow growth of the tumor and fixity to underlying tendon.8) MR features of giant cell tumor of tendon sheath are highly specific, which is low signal intensity on T2-weighted images, such as pigmented villonodular synovitis. Histologically, it is characterized by a pleomorphic cell population, which includes lipid-laden foam cells, multinucleated giant cells, and round or polygonal stromal cells, which are quite distinct from the histological features of nodular fasciitis.8)

Nodular fasciitis in the hand is also often mistaken for a soft tissue sarcoma, such as malignant fibrous histiocytoma or fibrosarcoma, because of its rapid growth, rich cellularity, and high mitotic activity.2,3,6) Thus, an incisional biopsy is usually recommended for a definite diagnosis. Unlike malignant histiocytoma, nodular fasciitis can be recognized by its more loosely arranged short bundles of fibroblasts and its prominent myxoid matrix. Additionally, the long, sweeping fascicular or herringbone pattern of malignant spindle cells, typical of fibrosarcomas, is never observed in nodular fasciitis.2)

Cortical erosion is associated with a large range of soft tissue tumors and other conditions. To the best of our knowledge, bone involvement associated with nodular fasciitis in the hand has been described in a few reports.9,10) Most occurrences of nodular fasciitis are indeed superficial, subcutaneous or fascia based, and distant from bone and periosteum. Moreover, nodular fasciitis usually presents as a rapidly growing mass leading to prompt surgical excision before bone involvement secondary to remodeling might be observed.9)

We experienced a very rare case of nodular fasciitis in the hand, associated with cortical erosion. Since this lesion may be confused with other neoplastic disease, we should emphasize the importance of a careful radiologic and histologic evaluation to avoid unnecessary aggressive surgery.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

A photograph showing the soft tissue mass, approximately 2 cm in diameter and located on the radial side of the proximal phalanx of the right thumb.

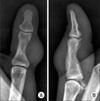

Fig. 2

(A) Anteroposterior and (B) lateral plain radiographs reveal the bone erosion of the radial side proximal phalanx close to the soft tissue mass.

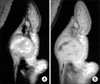

Fig. 3

Magnetic resonance images reveal that the well-circumscribed soft tissue mass, measuring 1.4 × 2.3 × 1.5 cm, has invaded the cortex and bone marrow of the mid-shaft of the proximal phalanx. The mass shows (A) iso-signal intensity on T1-weighted images, (B) heterogeneous, slightly high, signal intensity on T2-weighted images, and (C) strong enhancement on enhanced T1-weighted images.

Fig. 4

The mass shows some areas with (A) high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, and (B) no enhancement on enhanced T1-weighted images. This suggests that the mass might include necrotic or hemorrhagic components.

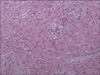

Fig. 5

A high-power view shows plump, randomly oriented spindle cells surrounded by myxoid stroma. Although cellularity of the lesion was high, hyperchromatism and variation in the size and shape of the nuclei were mild. Mitotic activity ranged from 5 to 10 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields, with no atypical forms identified (H&E, × 200).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to L. Malick for assistance with the final writing of this article.

References

1. Bernstein KE, Lattes R. Nodular (pseudosarcomatous) fasciitis, a nonrecurrent lesion: clinicopathologic study of 134 cases. Cancer. 1982. 49(8):1668–1678.

2. Katz MA, Beredjiklian PK, Wirganowicz PZ. Nodular fasciitis of the hand: a case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001. (382):108–111.

3. Rankin G, Kuschner SH, Gellman H. Nodular fasciitis: a rapidly growing tumor of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1991. 16(5):791–795.

4. Wang XL, De Schepper AM, Vanhoenacker F, et al. Nodular fasciitis: correlation of MRI findings and histopathology. Skeletal Radiol. 2002. 31(3):155–161.

5. Konwaler BE, Keasbey L, Kaplan L. Subcutaneous pseudosarcomatous fibromatosis (fasciitis). Am J Clin Pathol. 1955. 25(3):241–252.

6. Shimizu S, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Nodular fasciitis: an analysis of 250 patients. Pathology. 1984. 16(2):161–166.

7. Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD. Imaging of soft tissue tumors. 1997. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders;143–186.

8. Singh R, Sharma AK. Nodular fasciitis of the thumb: a case report. Hand Surg. 2004. 9(1):117–120.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download