Abstract

Background

Hemophiliacs have extrinsic tightness from quadriceps and flexion contractures. We sought to examine the effect of a focused physical therapy regimen geared to hemophilic total knee arthroplasty.

Methods

Twenty-four knees undergoing intensive hemophiliac-specific physical therapy after total knee arthroplasty, at an average age of 46 years, were followed to an average 50 months.

Results

For all patients, flexion contracture improved from -10.5 degrees preoperatively to -5.1 degrees at final follow-up (p = 0.02). Knees with preoperative flexion less than 90 degrees were compared to knees with preoperative flexion greater than 90 degrees. Patients with preoperative flexion less than 90 degrees experienced improved flexion (p = 0.02), along with improved arc range of motion (ROM) and decreased flexion contracture. For those patients with specific twelve-month and final follow-up data points, there was a significant gain in flexion between twelve months and final follow-up (p = 0.02).

Deficiency of clotting factors in hemophilia leads to recurrent bleeds in the synovial joints, oft en initiated through minimal trauma or even routine daily activity. Hemarthroses account for as much as 80% of hemorrhages seen in hemophiliacs,1) and the knee is the most common joint affected.2) Along with joint destruction and synovial hypertrophy, 3) fibrosis and contractures may occur as secondary complications of recurrent bleeds4) and result in significant pain and functional disability.5)

Multiple surgical interventions have been utilized to treat hemophiliac arthropathy in the knee, with total knee arthroplasty (TKA) becoming a safe and successful option for end-stage hemophiliac arthropathy.6) TKA is the most common procedure in hemophiliacs.7) Unlike other patients undergoing TKA, hemophiliac TKA patients have greater challenges, due to potential musculoskeletal bleeding complications in their postoperative rehabilitation.7,8) Hemophiliac patients suffer from widespread joint and soft tissue damage,9) and chronic inflammation leads to flexion deformity.4) As such, hemophiliacs have long-standing extrinsic tightness due to quadriceps/flexion contractures.

The surgical armamentarium for hemophiliac arthropathy is broad. Surgical treatment includes pseudotumor excision, synovectomy, soft tissue contracture release, tendon reconstruction, osteotomy, arthrodesis, and amputation.7) Many of these surgical modalities are undesirable or fraught with complications. For example, synovectomy is oft en complicated by recurrent joint bleeds from retained synovial tissue that leads to continued range of motion (ROM) limitations and chronic synovitis.4,5) In addition, once patients develop severe arthropathy, with significant osseous changes, TKA offers a more reliable solution for pain control and increased function.5) Like the patient who suffers from osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, once osseous changes occur, TKA becomes the best option.

When it comes to determining the success of TKA performed in a hemophiliac patient, preoperative ROM is the most important variable influencing outcomes.9) Historically, hemophiliac contractures have been corrected via surgical releases such as modified V-Y quadricepsplasty and/or posterior capsular release. However, these surgical options have fallen out of favor. Instead, attention has been focused onto TKA to address bony pathology, along with focused postoperative physical therapy (PT).

In the osteoarthritic patient who undergoes a TKA, literature has shown no significant improvements in ROM beyond twelve to eighteen months postoperatively.10) We hypothesized that hemophilic patients, through intensive postoperative therapy and intensive stretching of the quadriceps mechanism, may experience ROM improvements beyond a year and a half postoperatively. This study aims to 1) determine the ROM outcomes, especially after two years postoperatively, in hemophiliac patients after TKA, and 2) whether long-term improvements could be realized under the guidance of a therapist with experience working with this unique patient population.

This study evaluated twenty-four knees in fifteen patients who underwent TKA. The study was approved by the institutional review board. All surgeries were performed by a single fellowship-trained adult reconstruction surgeon. A standard medial parapatellar approach was used for all patients. A posterior stabilized (PS) prosthesis was used in all patients. The first four knees in three patients received a Press Fit Condylar PS implant (DePuy Inc., Warsaw, IN, USA); the remainder of the cohort was implanted with a NexGen Legacy PS prosthesis (Zimmer Inc., Warsaw, IN, USA).

Preoperative function and postoperative outcomes were quantitatively measured. Knee ROM data included passive flexion contracture, further flexion, and total knee arc ROM (knee flexion minus flexion contracture). These values were collected at the preoperative visit, as well as at approximately twelve and twenty-four months postoperatively. Knee motion gain was measured by subtracting knee arc at the preoperative time from the knee arc at twelve and twenty-four months, respectively. Finally, both preoperative (Fig. 1) and postoperative (Fig. 2) radiographs were obtained. Patient demographics, gender, age, duration of symptoms, and prior orthopedic surgeries were recorded. Any complications, such as infection or need for revision surgery, were documented.

Demographics were analyzed descriptively. Student's t-test was used to compare outcomes and ROM parameters at various follow-up time points. All statistics were calculated with SPSS ver. 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Key differences exist for the surgical management of hemophilia patients compared to the general population. These patients oft en have contracted and atrophied quadriceps as well as extensive intra-articular knee adhesions which compromise exposure. Care must be taken to avoid patellar tendon avulsion during exposure. A standard midline incision with median parapatellar arthrotomy is utilized. Release of intra-articular adhesions combined with tibial external rotation and a generous medial subperiosteal release diminishes tension on the patellar tendon and allows less forceful exposure minimizing the risks of fracture of the thin and osteopenic diaphysis often present in these patients. An extensive synovectomy, posterior capsular release, and medial and lateral gutter releases is generally required. A lateral retinacular release is often useful to minimizes tension on the patellar tendon during exposure and allow appropriate tracking and improved flexion postoperatively. Although a quadriceps snip is rarely necessary, we prefer to avoid tibial tubercle osteotomies in these patients due to concern for increased bleeding and compartment syndrome. Great care must be exercised to minimize the risk of neurovascular injury. The neurovascular structures in the popliteal fossa may be adherent to the posterior capsule. Joint contracture, fibrosis of muscles from intramuscular hematomae, and synovial hypertrophy may all affect the soft tissues and resulting soft-tissue balance. Indeed, arthrofibrosis, rather than instability, is generally the main challenge with hemophiliac arthropathy. The suprapatellar adipose tissue covering the distal femur should be preserved because it is a barrier to quadriceps adhesion. In patients in whom it has been replaced by fibrous tissue, restoration of motion is especially challenging. Bony erosion and periarticular cysts compromise bonestock, and may lead to intra-operative fracture with aggressive maneuvers. Epiphyseal hyperemia and synovial hypertrophy may cause widening of the distal femur compared to relatively narrow diaphyses. Severe patellar thinning may obviate the implantation of a patellar prosthesis. Angular deformity is quite common in advanced stages of disease, and tibial slope may be affected by long-standing flexion contractures. Cutting the tibia first may facilitate exposure for severe cases. At all points intra-operatively, meticulous hemostasis is essential. The surgeon may consider antibiotic-impregnated cement, as well as the use of surgical drains. A compressive wrap is utilized in the operative dressings, and a posterior splint may be used for the first couple postoperative days to protect a fragile soft tissue envelope. A careful series of postoperative examinations is important, as nerve palsy is a theoretical concern. Mechanical deep venous thromboembolic prophylaxis is used in light of the propensity for postoperative bleeding.

A careful preoperative assessment must be performed by a hematologist, including a pre-screen for neutralizing antibodies/factor inhibitors versus the potential recommendation for recombinant therapy. Ideally, this hematologist is familiar with the perioperative needs of the hemophiliac patient and will be available for inpatient consultation. The surgical team must also confirm that adequate factor stores are available at the inpatient pharmacy. Appropriate anesthesia consultation, including appropriate postoperative pain management, should be carefully planned and preoperative consultation with a pain management specialist is useful. Medical co-management of concomitant diseases like HIV and Hepatitis C proves important, and patients with these diseases should be counseled on the increased risks of postoperative infections. For maintenance of appropriate factor levels, home infusion monitoring may be needed for up to two weeks postoperatively.

All patients in this study met with the hemophilia treatment center physical therapist before and after surgery. The patients received PT starting on postoperative day one. Therapy sessions were carefully coordinated with factor replacement, and each session was matched to the patient to avoid exacerbation of pain or wound condition/hemostasis. The patients received at least one therapy session per day while hospitalized. Individualized home exercise programs were then provided upon discharge, and, in some cases, outpatient PT was initiated. Outpatient physical therapy was initially prescribed for four to six weeks postoperatively and tailored to the specific patient's needs and ROM. The patients attended regular visits with an outpatient therapist with extensive experience in managing hemophiliac patients and were followed periodically with this therapist for up to two years postoperatively. Physical therapy exercises typically included isometrics for the quadriceps, hamstrings and gluteal muscles, active and passive knee ROM exercises, and progressive resistive lower extremity exercises as the patient progressed. In addition, patients were instructed in adjuvant self-patellar mobility and scar management techniques in most cases. Functional mobility was also addressed, including the appropriate use of gait aids and adaptive equipment as necessary. While the therapy program used in this study has similarities to those employed in other studies, a particular difference may lie in the frequent follow-up, and the focus on quadriceps stretching/extrinsic tightness undertaken by a physical therapist experienced in hemophiliac arthropathy and post-surgical care. No patients required manipulation under anesthesia.

The mean patient age was 46 years old (range, 27 to 68 years; standard deviation [SD], 11). The average follow-up for patients was 50 months (range, 24 to 179 years; SD, 42). When analyzing ROM data for all patients collectively, there was no difference between preoperative flexion/arc (flexion minus flexion contracture) ROM and flexion/arc ROM at final follow-up. There was a significant difference between flexion contracture preoperatively and flexion contracture at final follow-up (p = 0.02). Flexion contracture, on average, improved from -10.5 degrees preoperatively (range, -30 to 2 degrees; SD, 10.2) to -5.1 degrees at final follow-up (range, -25 to 0 degrees; SD, 6.1) (Table 1).

Knees were further stratified into two groups: knees with preoperative flexion less than 90 degrees (11 knees in 8 patients; mean, 73 degrees) and knees with preoperative flexion greater than 90 degrees (13 knees in 9 patients; mean, 111 degrees); there was a significant difference between the means of the preoperative flexion between these two groups (p = 0.004). In those patients with preoperative flexion less than 90 degrees (mean, 73 degrees), there was a significant improvement in flexion from preoperative evaluation (range, 30 to 90 degrees; SD, 22.2) to final follow-up (mean, 88 degrees; range, 50 to 122 degrees; SD, 23.6; p = 0.02) (Table 2). Table 3 presents the specific ROM values for those patients with preoperative flexion greater than 90 degrees. For those patients with specific twelve-month and final follow-up data points (9 knees in 7 patients), there was a significant gain in flexion between twelve months and final follow-up (p = 0.02).

There were no nerve palsies or significant postoperative bleeding. There were no progressive radiolucent lines or hardware failure on postoperative radiographic assessment. There was one complication in the cohort. A 53-year-old African-American male experienced a periprosthetic joint infection in one of the two TKAs that had been performed. This TKA was explanted 42 months after the index TKA. He underwent replantation 10 months later in a two-stage process. At 59 months follow-up status post the second stage of reimplantation, there were no clinical issues or persistent infection.

The knee is the most commonly affected joint in hemophiliac bleeds,2) and the use of TKA in hemophiliac patients has shown great promise in reducing disability2,4,5,7,8) since the first TKA was performed on a hemophiliac in 1973.11,12) For the majority of hemophiliac patients who have undergone TKA, results have been described as favorable.13) However, many authors have reported a high rate of early and late complications, oft en related to infection and aseptic loosening.7,13,14) Restricted ROM is also a common concern seen in hemophiliac TKA. This study aimed to characterize the mid-term ROM results in this population, and to explore whether intensive physical therapy and stretching of the quadriceps mechanism could affect late postoperative ROM results.

Studies have noted much success with joint replacement surgery in patients with hemophilia.2,7,8,13) Silva and Luck13) evaluated 90 TKAs in 68 patients and found that 97% of patients had good or excellent Knee Society functional scores. The average flexion arc improved from 59 degrees to 69 degrees in the early postoperative phase, and then to 75 degrees at the latest follow-up of two years.13) Flexion contracture also improved from 18 degrees preoperatively to 9 degrees in the early postoperative phase and 8 degrees later.14) Similarly, Chiang et al.7) looked at 35 TKAs in 26 patients with mean preoperative ROM at 63.2 degrees and mean flexion contracture of 15 degrees. These variables improved to a mean postoperative ROM of 79.8 degrees and mean flexion contracture of 5.5 degrees.7) The patients in our study saw a comparable improvement with both flexion contracture and further flexion ROM gains. However, despite these obvious improvements in knee function, many authors cite the complications seen with TKA surgery in the hemophiliac patient. In the study of Chiang et al.,7) a failure rate of 14.3% was seen. If inadequate ROM was included in the definition of failure, the failure rate jumped to 22.9%. In fact, many authors consider inadequate ROM as one of the largest challenges in hemophiliac TKA.4,5,7,8,13) In the case of functional outcomes, restrictions in ROM were the most limiting factor in the Knee Society scores recorded in hemophiliac TKA patients.13,15) Increased stiffness seen in hemophiliacs has contributed to unsatisfactory gains in ROM following TKA.16) This stiffness tends to be the result of both intra- and extra-articular contractures associated with the recurrent bleeding and subsequent fibrosis that occurs in the joints and muscles of the lower extremity.17-19)

Many techniques have been incorporated into the TKA of hemophiliacs in order to overcome ROM shortcomings. Many focus on the knee joint itself: the structures posterior to the axis of knee rotation, such as the posterior capsule, posterior cruciate ligament, and hamstring tendons are often released to address contractures.4) While these structures are responsible for the flexion deformity seen in hemophiliac knees, their release and removal alone are not effective.20) Knees with hemophiliac arthropathy are characterized by the presence of arthrofibrosis that limits ROM by forming bands of scar tissue between the quadriceps mechanism and the distal femur.17) As such, it is not always the knee joint itself that contains the limiting factor. Oft en, the musculature of the upper leg limits ROM, and quadricepsplasty has been employed to address this extrinsic tightness.

Rehabilitation after surgery is, in fact, a key component to a patient's success. Incorporating a rigorous and appropriate physiotherapy for hemophiliac patients undergoing TKA is important to the success and gains in their ROM. However, the use of rehabilitation therapy is one of the least studied aspects of perioperative management in TKA.17) This lack of research hinders the surgeon's ability to facilitate the direction of physiotherapy after TKA.21) Historically, the preoperative ROM for patients undergoing TKA was the best predictor of their postoperative ROM.9) Patients with a preoperative flexion of less than 50 degrees often achieved a maximum flexion range of only 90 degrees, whereas those with a preoperative flexion greater than 65 degrees achieved between 100-130 degrees of flexion postoperatively.22) Lobet et al.17) found that a deficit in extension postoperatively was more likely present in knees with significant flexion contracture preoperatively. In contrast, Mockford et al.10) found that patients tended to migrate towards a "middle range," where those with poor preoperative flexion gained flexion after TKA, while those with satisfactory preoperative flexion lost theirs. Similarly, Lizaur et al.23) found that patients with the stiffest knees were afforded the greatest improvements. In our study, those patients with the poorest flexion benefited the greatest from an intense postoperative rehabilitation course, with a focus quadriceps stretching performed by a therapist familiar with the hemophiliac population.

Although limited in number, previous studies looking at PT regimens have shown positive ROM gains in patients. A study by Shoji et al.24) found that patients who underwent organized daily PT for one month after TKA had better knee flexion at two to nine years follow-up than patients with only two weeks of organized physiotherapy. Similarly, Moffet et al.25) emphasized the effectiveness of intensive functional rehab, with those receiving twelve sessions between two and four months showing less pain and stiffness in comparison to those who did not. Results such as these have led some authors to suggest that long term rehabilitation protocols be recommended for all hemophiliacs with a TKA. It should focus on restoring ROM in flexion and extension, muscular strengthening, and proprioceptive performance.17) While flexion contracture in osteoarthritic patients may be best improved at the time of surgery,23) hemophiliacs may also benefit from soft tissue stretching post-surgery.

It is of critical importance that surgeons be aware of the potential for later improvements in ROM in long-standing extrinsic knee contracture. This data may suggest an increased threshold prior to considering a quadricepsplasty, which acutely lengthens the quadriceps at the expense of either quadriceps weakness or an extensor lag. Instead of quadricepsplasty as a first-line treatment, hemophiliac patients may rather undergo TKA alone with aggressive but appropriate postoperative rehabilitation to realize increased ROM benefits. While not directly studied here, these improvements in ROM may also occur in juvenile idiopathic arthritis or other childhood onset conditions where extrinsic muscle shortening limits ROM.

There are limitations to this study. This retrospective study involves a relatively small patient cohort given the low numbers of hemophilic TKA versus the general population. Moreover, this condition and its management is generally limited to institutions that have hemophilia treatment centers that are adequately equipped to provide coordinated, multidisciplinary care. While TKA in hemophiliacs is not common in community-based practices, the PT principles and postoperative gains in motion - and the intra-operative and postoperative distinctions from the osteoarthritic or rheumatoid population - are important. More study in larger numbers is needed to confirm this initial observation in hemophiliac arthropathy, along with other conditions with extrinsic tightness, including juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

In conclusion, the rehabilitation after hemophiliac TKA patients is challenging. Hemophiliacs may experience ROM improvements with intensive stretching of the quadriceps mechanism and hamstrings to a more functional length. Those patients with the poorest preoperative flexion (less than 90 degrees) realized the greatest gains. Importantly, this study provides motivation for hemophiliac patients in terms of long-term improvements after total knee arthroplasty.

Figures and Tables

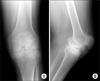

Fig. 1

Preoperative anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs demonstrating severe arthropathy of the knee secondary to hemophilia.

Fig. 2

Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of the knee at six year follow-up examination.

Table 2

Range-of-Motion Values for Patients with Preoperative Flexion Less than 90 Degrees (n = 11 knees)

References

2. Norian JM, Ries MD, Karp S, Hambleton J. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthropathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002. 84(7):1138–1141.

3. Siegel HJ, Luck JV Jr, Siegel ME, Quinones C. Phosphate-32 colloid radiosynovectomy in hemophilia: outcome of 125 procedures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001. (392):409–417.

4. Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Correction of fixed contractures during total knee arthroplasty in haemophiliacs. Haemophilia. 1999. 5:Suppl 1. 33–38.

5. Bae DK, Yoon KH, Kim HS, Song SJ. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthropathy of the knee. J Arthroplasty. 2005. 20(5):664–668.

6. Legroux-Gerot I, Strouk G, Parquet A, Goodemand J, Gougeon F, Duquesnoy B. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthropathy. Joint Bone Spine. 2003. 70(1):22–32.

7. Chiang CC, Chen PQ, Shen MC, Tsai W. Total knee arthroplasty for severe haemophilic arthropathy: long-term experience in Taiwan. Haemophilia. 2008. 14(4):828–834.

8. Figgie MP, Goldberg VM, Figgie HE 3rd, Heiple KG, Sobel M. Total knee arthroplasty for the treatment of chronic hemophilic arthropathy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989. (248):98–107.

9. De Kleijn P, Blamey G, Zourikian N, Dalzell R, Lobet S. Physiotherapy following elective orthopaedic procedures. Haemophilia. 2006. 12:Suppl 3. 108–112.

10. Mockford BJ, Thompson NW, Humphreys P, Beverland DE. Does a standard outpatient physiotherapy regime improve the range of knee motion after primary total knee arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2008. 23(8):1110–1114.

11. Lachiewicz PF, Inglis AE, Insall JN, Sculco TP, Hilgartner MW, Bussel JB. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985. 67(9):1361–1366.

12. Luck JV Jr, Kasper CK. Surgical management of advanced hemophilic arthropathy: an overview of 20 years' experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989. (242):60–82.

13. Silva M, Luck JV Jr. Long-term results of primary total knee replacement in patients with hemophilia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005. 87(1):85–91.

14. Goddard NJ, Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Wiedel JD. Total knee replacement in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2002. 8(3):382–386.

15. Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Total knee replacement in haemophilic arthropathy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007. 89(2):186–188.

16. Tamurian RM, Spencer EE, Wojtys EM. The role of arthroscopic synovectomy in the management of hemarthrosis in hemophilia patients: financial perspectives. Arthroscopy. 2002. 18(7):789–794.

17. Lobet S, Pendeville E, Dalzell R, et al. The role of physiotherapy after total knee arthroplasty in patients with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2008. 14(5):989–998.

18. Atkins RM, Henderson NJ, Duthie RB. Joint contractures in the hemophilias. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987. (219):97–106.

19. Miller MD. Review of orthopaedics. 2004. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders.

20. Sheth DS, Oldfield D, Ambrose C, Clyburn T. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthropathy. J Arthroplasty. 2004. 19(1):56–60.

21. Naylor J, Harmer A, Fransen M, Crosbie J, Innes L. Status of physiotherapy rehabilitation after total knee replacement in Australia. Physiother Res Int. 2006. 11(1):35–47.

22. Defalque A, Lobet S, Pothen D, Hermans C, Poilvache P. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthroplasty: retrospective study of the functional improvement. In : Word Federation of Hemophilia 9th Musculoskeletal Congress; 2005 July 9-11; Istanbul, Turkey.

23. Lizaur A, Marco L, Cebrian R. Preoperative factors influencing the range of movement after total knee arthroplasty for severe osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997. 79(4):626–629.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download