Abstract

Trigger point injection is a simple procedure that is widely performed for relieving pain. Even though there are several complications of trigger point injection, myositis ossificans has not been documented as one of its complications. We treated a patient who suffered from painful limitation of elbow motion and this was caused by myositis ossificans between the insertions of brachialis and supinator muscles after a trigger point injection containing lidocaine mixed with saline, and we also review the relevant medical literature.

Trigger point injection (TPI) has been proved to be useful to relieve myofascial pain that is unresponsive to several medical treatments. TPI using lidocaine or steroid injection with a 24 or 26 gauge needle to the trigger point results in favorable pain relief. Although TPI is known to be a relatively safe procedure, several complications caused by TPI such as aggravation of localized pain at the site of injection, hematoma, infection and hypokalemic paralysis have all been reported.1)

Heterotopic ossification refers to the formation of mature lamellar bone in nonosseus tissue and it can occur in anywhere of the body. Myositis ossificans (MO) is defined as abnormal formation of bone in inflammatory muscle. MO can often be misdiagnosed as intramuscular hematoma or simple contusion, which might lead to poor outcomes. Furthermore, when the MO particularly occurs near a joint, it causes a functional deficit in addition to the pain. The common causes of MO are direct trauma, including fracture and dislocation, burns and neurologic injuries such as brain trauma or spinal cord injury. However, MO caused by TPI has not been documented as a complication of TPIs.

We treated a patient who suffered from painful limitation of elbow motion and this was caused by MO between the insertion of the brachialis and supinator muscles after TPI containing lidocaine mixed with saline. We also review the relevant medical literature.

A 31-year-old male patient visited the outpatient clinic suffering from mild pain at his left elbow and he had had this pain for the previous 3 weeks. He was a businessman without a history of trauma. His medical history was unremarkable and he had not participated in any regular sports activities that may have caused repetitive trivial trauma on his left elbow joint. About 3 weeks prior to visiting the hospital, mild pain on the anterior aspect of the elbow muscle occurred after casually catching and throwing a ball. He was treated for his elbow pain by TPI containing 0.5 mL of 2% lidocaine and 1.5 mL of normal saline at another hospital. At 2 weeks after injection, swelling, redness and pain of his left elbow had developed. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and physical therapy for 2 weeks were prescribed at the same hospital, but the symptoms were aggravated and he was finally referred to our hospital.

On the initial visit to our outpatient clinic, the physical examination revealed moderate swelling, local heating, redness and tenderness at the left elbow joint. The range of motion of the elbow joint was also decreased. Extension of 20 degrees and further flexion of 130 degrees were measured. There were no motor deficits or neurologic symptoms. There was no palpable mass around the elbow joint. Considering his injection history and the clinical findings, we presumed the probable diagnosis was infection such as cellulitis or septic arthritis. Therefore, laboratory studies for infectious disease, including blood tests, a plain radiograph and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), were evaluated. The laboratory tests were unremarkable except for an increased erythocyte sediment rate (ESR); the white blood count was 8,300/uL (neutrophils, 55.8%; monocytes, 7.2%; eosinphils, 0.8%; basophils, 0.4%), the ESR was 32 mm/hour and the C-reactive protein was 0.3 mg/dL. The plain radiograph of the left elbow joint showed moderate swelling of the soft tissue around the elbow joint, but the other findings were nonspecific (Fig. 1). MRI revealed a suspicious lesion between the insertion of the brachialis and supinator muscles and this was regarded as inflammatory tissue without formation of an abscess pocket. This lesion showed low signal intensity on the T1-weighted image, high signal intensity on the T2-weighted image and strong enhancement by gadolinium-DTPA (Fig. 2). Therefore, a provisional diagnosis of deep soft tissue infection was made and empirical IV antibiotics therapy consisting of flomoxef sodium 1 gm and isepamicin sulfate 200 mg was started every 8 hours at 3 days after an admission.

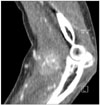

Despite conservative treatments for 2 weeks, the pain and limitation of motion were aggravated. At about 6 weeks after TPI, the range of motion was restricted to extension of 30 degrees and further flexion of 90 degrees. A palpable mass (4 × 5 cm in size) was found on the anterior aspect of the elbow. Ultrasonography was performed to differentiate between infection and other diseases. Ultrasonography showed a hypoechoic area with irregular margins and posterior shadowing (Fig. 3). Because these findings increased the possibility of calcification, computed tomography (CT) was done for further evaluation of the lesion showing calcification. On CT, a 4 × 4.6 cm sized high-density mass that was enhanced at 24 Hounsfield units and that was consistent with calcification was found between the brachialis and supinator muscles (Fig. 4). According to the radiographic evaluations, we made a final diagnosis as MO of the elbow muscle. We planned to delay surgical management until the mass was fully mature. However, the limitation of elbow motion was more aggravated and his severe elbow pain was not relieved by medications. The authors believed that surgical excision would be helpful to prevent stiffness of the elbow joint and avoid compression of the adjacent neurovascular structure. At 8 weeks after TPI, surgical excision was performed through the anterior approach. The mass was easily isolated without adjacent muscular or neurovascular injuries. Grossly, the excised mass had dark brown colored soft tissue on the peripheral portion and a white central lesion and its size measured 3.5 × 3 × 1.5 cm. The histological findings demonstrated extensive osteoid formation rimmed by osteoblasts and a few inflammatory cells. The rough zoning and inconspicuous cellular atypia were features for MO rather than extraskeletal osteosarcoma (Fig. 5).

We prescribed NSAIDs (indomethacin) and radiation therapy. Radiation therapy started from postoperative 1 day and this was performed for 3 days (daily dose, 200 cGy; total dose, 600 cGy). His symptoms improved considerably after surgical excision. The full range of elbow motion was restored 2 months after the surgical excision. At the 3 years follow-up, the patient had no recurrence of pain and he had full range of motion.

We successfully treated a patient who had traumatic MO between the brachialis and supinator muscles after TPI. MO of the elbow joint is usually related to remarkable trauma. Thompson and Garcia2) reported that MO developed in 3% of all patients with elbow dislocations without fractures and in 20% of all dislocations combined with fractures. But in this report, MO developed at the elbow after TPI without predisposing factors like definite trauma or repeated trivial injuries. MO as a complication of injection is a rare complication and there are not many such reports in the medical literature. Kaminsky et al.3) reported MO that occurred in a foot after a single steroid injection to treat pain in the plantar arch. Gunduz et al.4) reported MO in the quadriceps muscles due to repeated injections of low-molecular weight heparin for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis. Schroder et al.5) reported on three infants who showed severe calcification in thigh injection sites following daily vitamin E injections for the first 3 weeks of life. Although the causes and mechanism of MO induced by needling remain unclear, we can hypothesize that the MO in our patient began with hemorrhage or hematoma caused by needling, and lidocaine may have had a role as a chemical reactant. Therefore, needling may cause hemorrhage, release of calcium from muscle, vascular stasis and tissue hypoxia, which are local factors for inducing MO.

MO typically presents with pain and an enlarging mass in the affected areas. Edema, warmth, redness, fever and a restricted range of motion are common features of MO. Because of its clinical manifestations, MO may occasionally be misdiagnosed as deep vein thrombosis or infectious disease, including cellulitis or osteomyelitis. MO is sometimes confused with malignant tumor such as a sarcoma. However, MO can be distinguished from malignant tumor by its unique histological finding, called 'zonal phenomenon.' Radiographs are the preferred method for the initial assessment for MO. Soft tissue swelling is the earliest radiographic finding. An abnormal finding like calcification usually appears after 2 to 3 weeks, but often an abnormal finding may be not seen until 4 to 5 weeks after injury. However, our radiographs obtained at 4 weeks after TPI didn't show calcification and instead they showed soft tissue swelling. In general, the MRI findings in MO are rather nonspecific owing to different phases.6) Some authors6,7) have postulated that a low signal intensity rim on T1 and T2-weighted images are a common finding that reflect the beginning of peripheral calcification in MO. However, this finding did not appear in our patient, although the histological findings showed peripheral osteoid formation. Ultrasonography is not generally used to assess MO, but this patient underwent ultrasonography 3 weeks after admission to evaluate any changes like abscess formation. We incidentally observed a lesion that was suspected to be calcification and we performed CT to evaluate its size and position.

The treatment of MO is based on conservative management. NSAIDs such as indomethacin are commonly used. Wieder8) reported successful outcomes for the treatment of MO using acetic acid iontophoresis. Radiation therapy has been established in the treatment for MO. It is thought that radiation inhibit the fast-dividing osteoprogenitor cells from differentiating into osteoblasts. Low doses below 1,000 cGy of radiation have been established as effective treatment for MO without any risk of radiation-induced sarcoma.9) In this case, we performed 600 cGy of radiation therapy after mass excision.

The timing of surgical intervention is still being debated because operating during the active phase can be another risk factor for recurrence. In general, surgical excision is recommended when the lesions are completely mature on a 3-phase bone scan, there is a normalized level of alkaline phosphatase or the absence of acute symptoms. However, early surgical excision is recommended when severe joint ankylosis is anticipated due to rapid and significantly limited range of motion. We decided on surgical intervention 8 weeks after the symptoms developed because the patient had aggravating pain and progressive limitation of the range of motion. We think that operative treatment might be considered to prevent ankylosis of a joint or poor outcomes when stiffness of a joint rapidly develops. Viola and Hastings10) recently reported satisfactory results with early intervention 3 to 6 months after injury.

The initial diagnosis of this patient was undefined because this patient was referred from another hospital after the symptoms were aggravated. Considering the patient's history, the most probable diagnosis could be lateral epicondylitis. Even though TPI is generally performed for the treatment of myofascial tenderness points, which are defined as hyperirritable points located within a taut band of any skeletal muscle or fascia, TPI would be inappropriate for the initial treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Although TPI is known to be a relatively safe procedure, an accurate diagnosis should be made before TPI to prevent the overuse of TPI.

We experienced a patient who had MO in the elbow without any predisposing factors except TPI containing lidocaine, and we obtained a good clinical outcome after early surgical intervention. Although MO of the elbow commonly occurs after severe or repetitive trivial trauma, TPI containing lidocaine also can lead to MO.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

The preoperative anterior/posterior and lateral radiographs showed soft tissue swelling without a bony lesion.

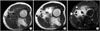

Fig. 2

Magnetic resonance imaging noted a suspicious lesion between the insertion of the brachialis and supinator muscles, and this lesion was regarded as inflammatory tissue without formation of an abscess pocket. This lesion showed (A) low signal intensity on the T1-weighted axial image, (B) high signal intensity on the T2-weighted axial image and (C) a strongly enhanced T1-weighted axial image by gadolinium-DTPA.

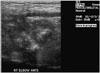

Fig. 3

Ultrasonography demonstrated a hypoechoic area with irregular margins and posterior shadowing.

References

1. Cheng J, Abdi S. Complications of joint, tendon, and muscle injections. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag. 2007. 11(3):141–147.

2. Thompson HC 3rd, Garcia A. Myositis ossificans: aftermath of elbow injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1967. 50:129–134.

3. Kaminsky SL, Corcoran D, Chubb WF, Pulla RJ. Myositis ossificans: pedal manifestations. J Foot Surg. 1992. 31(2):173–181.

4. Gunduz B, Erhan B, Demir Y. Subcutaneous injections as a risk factor of myositis ossificans traumatica in spinal cord injury. Int J Rehabil Res. 2007. 30(1):87–90.

5. Schroder H, Schulz M, Aeissen K. Muscular calcification following injection of vitamin E in newborn infants. Eur J Pediatr. 1984. 142(2):145–146.

6. Shirkhoda A, Armin AR, Bis KG, Makris J, Irwin RB, Shetty AN. MR imaging of myositis ossificans: variable patterns at different stages. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1995. 5(3):287–292.

7. De Smet AA, Norris MA, Fisher DR. Magnetic resonance imaging of myositis ossificans: analysis of seven cases. Skeletal Radiol. 1992. 21(8):503–507.

8. Wieder DL. Treatment of traumatic myositis ossificans with acetic acid iontophoresis. Phys Ther. 1992. 72(2):133–137.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download