Abstract

Background

There is a worldwide tendency of an increasing prevalence of obesity. Therefore, this study aimed at determining whether such a trend exists among cerebral palsy (CP) patients. We also tried to compare this trend with the trend in the general population. We also discuss the importance of obesity trends in CP patients.

Methods

This retrospective study was performed on 766 ambulatory patients who were diagnosed with CP since 1996 in our institution. The associations among the prevalence of obesity and the body mass index, age, gender, the type of CP, the gross motor function classification system and the time of survey were investigated.

Results

The overall prevalence of obesity was 5.7%, and the overall prevalence of obesity together with being overweight was 14.6% for the ambulatory patients with CP. The prevalence of obesity and of obesity together with being overweight did not show a statistically significant temporal increase. On the other hand, age and gender were found to affect the body mass index of the ambulatory CP patients (p < 0.001 and 0.003, respectively).

Conclusions

The extent of obesity and being overweight in the ambulatory patients with CP in this study was far less than that reported in the United States (US). In addition, it appears that the differences of the prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents between those with and without CP are disappearing in the US, whereas the differences of the prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents between those with and without CP seem to be becoming more obvious in Korea. Accordingly, care should be taken when adopting the data originating from the US because this data might be affected by the greater prevalence of obesity and the generally higher body mass indices of the US.

The prevalence of obesity continues to increase worldwide.1) The Korean National Growth Charts (2007) show that the prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents was 9.7% in 2005, which is 1.7 times higher than 5.8% reported in 1997.2) According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which have monitored the prevalence of obesity in the United States (US) since the early 1960s, the prevalence of being overweight among children and adolescents has more than tripled during the past three decades.3,4)

Cerebral palsy (CP) is defined as a group of activity-limiting disorders associated with the development of movement and posture. These disorders are attributed to non-progressive disturbances that occur in the fetal or infant brain during development. Furthermore, the motor disorders of CP are often accompanied by disturbances of sensation, cognition, communication, perception and/or behavior, and a seizure disorder.5)

Children with CP used to be considered small for their age in terms of height and weight. However, Rogozinski et al.6) reported that the prevalence of obesity among ambulatory children with CP has increased over a decade in the US, i.e., from 7.7% during 1994-1997 to 16.5% during 2003-2004. Furthermore, it has been reported that being overweight and the risk of being overweight among the patients with CP is greater than that of the general population.7) However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has documented the prevalence of obesity in ambulatory Korean children with CP.

The purposes of this study were to characterize the trends in the prevalence of obesity and in the body mass index (BMI) of Korean children and adolescents with CP, and to determine the relationships between obesity and gender, age, the physical classification of CP and the functional level (as determined by the gross motor function classification system [GMFCS]). In addition, we compared the trends in the prevalence of obesity among ambulatory children and adolescents with CP with those of children in the general population in Korea and the US.

This study was conducted retrospectively. Our hospital is a tertiary referral center for patients with CP. The inclusion criteria were as follows: the patients who were admitted since 1996, they were ambulatory patients with CP (GMFCS8) levels I-III), their age was between 2 to 19 years and the availability of body weight and height data. A total of 766 patients were enrolled in this study. We documented the time of measurement, the age at measurement, the body weight, height and gender, the physical classification of CP, i.e., unilateral involvement (hemiplegia or monoplegia) or bilateral involvement (diplegia, triplegia or quadriplegia), and the GMFCS level for each patient by chart review. The times of measurement were categorized as follows: the 1st period from 1996 to 2000 (n = 196, 25.6%), the 2nd period from 2001 to 2005 (n = 323, 42.2%) and the 3rd period from 2006 to September 2008 (n = 247, 32.2%). We then divided the patients into 3 groups based on age at the time of measurement: 2 to 6 years as the 1st age group (n = 261, 34.1%), 7 to 12 years as the 2nd age group (n = 344, 44.9%) and 13 to 19 years as the 3rd age group (n = 161, 21.0%). The GMFCS levels were retrospectively evaluated based on chart reviews of the functional statuses.

Obesity was defined as a BMI > the 95th percentile on the gender specific BMI-for-age growth charts,9) or as an absolute BMI of > 25 kg/m2. Being overweight was defined as a BMI > the 85th percentile, but < the 95th percentile according to the gender specific BMI-for-age growth charts.2,9) BMI percentiles were calculated according to the 2007 Korean Children and Adolescents Growth Standard.10) Using the data from the 2003-2004 NHANES and a previous study,6) the prevalence of obesity was compared between the ambulatory children and adolescents with CP and the general children and adolescents in Korea and the US.

The data was analyzed using SPSS ver. 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The two-sample t-test was used to compare the means of two independent variables, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the means of three or more independent variables. Duncan's test and Dunnett's T3 test were used for post-hoc analysis, and Pearson's chi-square test for two independent frequencies and Cochran's Q test for three or more independent frequency were used to compare prevalences. Statistical significance was accepted for p < 0.05.

The patients' characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean body weights and mean heights of the ambulatory patients with CP increased over the study period. The overall body weight and height increased significantly by 14.2% and 5.0%, respectively, between the 1st and 3rd periods (p = 0.009 and 0.002, respectively).

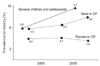

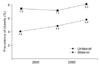

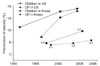

However, this change was no surprise because the mean age of the 3rd period was higher than that of the 1st period. The overall prevalence of obesity was 5.7% (44/766) and the overall prevalence of obesity together with being overweight was 14.6% (112/766). However, the prevalence of obesity and being overweight did not change significantly over the study period (p = 0.814 for obese, p = 0.665 for obese and overweight). In addition, no significant increase in the prevalence of obesity or in the BMI for each characteristic was observed between the three study periods (Tables 2 and 3). However, the BMI was found to significantly increase with age (p < 0.001, from 16.1 kg/m2 for 2-6 year olds to 20.0 kg/m2 for 13-19 year olds), and the BMI was also significantly greater for males than for females (p = 0.003, 17.8 kg/m2 for males and 17.0 kg/m2 for females). Nevertheless, the prevalence of obesity was not found to be significantly related to age (p = 0.149, 5.7% in 2-6 year olds and 8.7% in 13-19 year olds), gender (p = 0.098, 6.8% for males and 3.9% for females) (Fig. 1), the type of CP (p = 0.191, 7.6% for unilateral involvement, 5.1% for bilateral involvement) (Fig. 2), and the GMFCS level (p = 0.426, 6.1% for level I or II, and 4.5% for level III). The BMI was also not significant affected by the type of CP (p = 0.408, 17.7 kg/m2 for unilateral involvement, 17.4 kg/m2 for bilateral involvement) or the GMFCS level (p = 0.191, 17.6 kg/m2 for level I or II, 17.2 kg/m2 for level III). The prevalence of obesity has tended to converge in the US, but in Korea it has tended to diverged (Fig. 3).

Even though the prevalence of obesity among ambulatory CP patients in the US is significantly increasing, in this study, there was no significant increase of the prevalence of obesity in Korean patients. Furthermore, the extents of obesity and being overweight were far less than those reported in the US. In addition, it appears that differences of the prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents between those with and without CP are disappearing in the US, whereas the prevalence of obesity in Korean children and adolescents between those with and without CP seems to be becoming more obvious (Fig. 3). For some kinds of diseases, the Korean government and medical service administrators have tended to accept the policies adopted in the US. However, as is shown by the present study, the data can be misleading if it is extracted from a distant source without consideration of the local environment such as the prevalence of obesity, etc. Accordingly, care should be taken when adopting data originating from the US because it might be affected by a greater prevalence of obesity and the generally higher body mass indices. However, it is also possible that the prevalence of obesity among ambulatory CP patients in Korea will increase to the levels in the US. Accordingly, we advocate that the prevalence and trends of obesity in CP patients should be monitored. The BMI of CP patients showed a significant increase with age (p < 0.001) and the BMI was higher among males than among females (p = 0.003). This trend was similar with that of the general children/adolescents in Korea.2,9,10) We believe that the prevalence of obesity was not significantly different between each of the age groups and between each gender because the gender specific BMI according to age/growth charts, which are used to define obesity, is higher for males than for females and it is also higher for older ages than for younger ages.

Taylor et al.11) found that obese children self-reported greater impairment of mobility than did children who were not obese. There's some possible explanation that such a result is due to the relatively insufficient muscle strength and increased cardiorespiratory effort required for over-weighted persons.12-14) CP is a neuromuscular disorder that causes limitations of activity,5) so it may be substantially more challenging for CP patients with a higher BMI to perform activities than it is for other CP patients with a lower BMI (same height with a lower weight). Notably, Gough et al.15) found that non-operative intervention may be less effective in ambulant males with bilateral spastic CP than ambulant females with bilateral spastic CP, and additionally, ambulant males with bilateral spastic CP are more likely to have surgery recommended than the ambulant females with bilateral spastic CP and who are of similar gestational and chronological ages and who have similar GMFCS levels. Although this study was performed just on ambulatory CP patients in one institution, we think the fact that the higher BMI in males than that in females could be one possible explanation for such a poorer result for the males with CP than that for the females with CP.

Some weaknesses of this study should be considered. First, this study was clinic-based study in a single institution, and so may not reflect the general population. However, no previous study has been conducted on obesity among CP patients in Korea, and so we believe that this study represents a significant advance in our understanding. Second, because the body weight and height were only available for the admitted patients, the non-admitted patients with CP were excluded from this study. Finally, the GMFCS levels were not checked at admission, rather, they were retrospectively checked by chart review. On reviewing the charts for checking the GMFCS levels, we found out that we were unable to determine whether 44 (5.7%) patients were of GMFCS level I or II, but in no case did we fail to differentiate the patients of level II or III (Table 1). Based on our findings, the proportion of undeterminable GMFCS levels decreased with time (16.8% in the 1st period, 3.4% in the 2nd period and 0% in the 3rd period). Thus, we believe that before the development of the GMFCS in 1997, physicians paid more attention to whether patients could walk with/without orthosis, which would differentiate GMFCS levels II and III better than whether patients could walk a long distance or run, which would differentiate GMFCS level I and II, but we believe that after the development of the GMFCS, physicians started to pay more attention than before to whether patients could walk long distances or run.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

The prevalence of obesity in male and female Korean ambulatory children and adolescents with cerebral palsy (CP) by the year. 'General children and adolescents' means the general children and adolescents in Korea, 'Males with CP' means male Korean ambulatory children and adolescents with CP, 'Females with CP' means female Korean ambulatory children and adolescents with CP. The prevalence of obesity in males was higher than that of the females at all times. Although the BMI showed significant difference between the males and females (p = 0.003, not shown as a graph), the differences between the prevalence of obesity in the males and females were not significant (p = 0.098).

Fig. 2

Prevalence of obesity among Korean ambulatory children and adolescents with cerebral palsy with respect to unilateral and bilateral involvements by the year. The prevalence of obesity among those with unilateral involvement was non-significantly greater than that among those with bilateral involvement throughout the study period (p = 0.191).

Fig. 3

Prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents in the general population and in ambulatory children and adolescents with cerebral palsy (CP) by the year in Korea and the United States (US). The prevalence of obesity has tended to converge in the US, but in Korea it has diverged.

References

1. Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Childhood obesity: public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet. 2002. 360(9331):473–482.

2. Oh K, Jang MJ, Lee NY, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among Korean children and adolescents in 1997 and 2005. Korean J Pediatr. 2008. 51(9):950–955.

3. Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999-2000. JAMA. 2002. 288(14):1728–1732.

4. Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002. JAMA. 2004. 291(23):2847–2850.

5. Bax M, Goldstein M, Rosenbaum P, et al. Proposed definition and classification of cerebral palsy, April 2005. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005. 47(8):571–576.

6. Rogozinski BM, Davids JR, Davis RB, et al. Prevalence of obesity in ambulatory children with cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007. 89(11):2421–2426.

7. Hurvitz EA, Green LB, Hornyak JE, Khurana SR, Koch LG. Body mass index measures in children with cerebral palsy related to gross motor function classification: a clinic-based study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008. 87(5):395–403.

8. Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997. 39(4):214–223.

9. Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000. 320(7244):1240–1243.

10. Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The Korean Pediatric Society. The Committee for the Development of Growth Standard for Korean Children and Adolescents. 2007 Korean children and adolescents growth standard (commentary for the development of 2007 growth charts) [Internet]. 2007. cited 2010 Mar 10. Seoul: Division of Chronic Disease Surveillance;Available from: http://www.cdc.go.kr/.

11. Taylor ED, Theim KR, Mirch MC, et al. Orthopedic complications of overweight in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2006. 117(6):2167–2174.

12. Lundberg A. Maximal aerobic capacity of young people with spastic cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1978. 20(2):205–210.

13. Norman AC, Drinkard B, McDuffie JR, Ghorbani S, Yanoff LB, Yanovski JA. Influence of excess adiposity on exercise fitness and performance in overweight children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005. 115(6):e690–e696.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download