Abstract

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a deep infection of the subcutaneous tissue that progressively destroys fascia and fat; it is associated with systemic toxicity, a fulminant course, and high mortality. NF most frequently develops from trauma that compromises skin integrity, and is more common in patients with predisposing medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, alcoholism, renal disease, liver disease, immunosuppression, malignancy, or corticosteroid use. Most often, NF is caused by polymicrobial pathogens including aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. NF caused by Staphylococcus aureus as a single pathogen, however, is rare. Here we report a case of NF that developed in a healthy woman after an isolated shoulder sprain that occurred without breaking a skin barrier, and was caused by Staphylococcus aureus as a single pathogen.

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a rare soft tissue infection with a very high rate of mortality unless promptly recognized and aggressively treated. Early recognition and prompt medical and surgical treatment are mandatory to achieve a successful outcome. NF usually develops from the trauma caused by breaking a skin barrier and is more common in patients with preexisting disease. Here we report a case of NF that developed in a previously healthy woman after a shoulder sprain, without an open wound, caused by Staphylococcus aureus as a single pathogen.

A 49-year-old female visited our emergency department complaining of left shoulder and arm pain that was induced by the traction of a seat belt improperly fastened under her arm during a traffic accident. She had neither a history of shoulder and arm troubles nor any other preexisting medical problems.

She was alert and oriented at her visit. Body temperature was 37.2°, blood pressure was 120/80 mmHg, and the pulse rate was 80 beats/minute and regular. The physical examination showed tenderness of the left arm and limited range of motion of the left shoulder. Neither an external wound nor discoloration was identified. The initial X-ray showed no specific findings. She was admitted for conservative treatment.

On the second day, the patient complained of a progressive increase in pain of the left shoulder and arm area. During the following 24 hours, the patient was distressed and agitated by severe pain with a fever of 38.5°, blood pressure of 150/90 mmHg, tachycardia of 120 beats/minute, and oliguria. The entire left arm was swollen with a large area of red-purplish skin. Bullae had formed, and the crepitus was palpable, extending to the neck and left chest wall. Laboratory findings revealed a white blood cell count of 10,000/mm3 (normal range, 4,000 to 11,000/mm3), platelet count of 175,000 mm3 (range, 140,000 to 440,000 mm3), blood urea nitrogen of 8 mg/dL (range, 8 to 20 mg/dL), creatinine of 0.5 mg/dL (range, 0 to 0.5 mg/dL), erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 49 second (range, 0 to 15 second), and C-reactive protein of 27.47 mg/dL (range, 0 to 0.5 mg/dL). At this time, follow-up radiography demonstrated subcutaneous emphysema from the left arm to the ipsilateral shoulder, neck, and lateral chest wall (Fig. 1). Gas gangrene was diagnosed and empirical, high-dose, broad-spectrum antibiotics (ceftriaxone, clindamycin, aminoglycoside) were intravenously administered after consultation with the department of infectious disease. The patient underwent emergency surgery within three hours after the clinical symptoms manifested.

As soon as an incision was made, a considerable amount of foul-odorous purulent pus flowed out from the wound. The skin, subcutaneous tissue and fascia overlying the biceps and deltoid muscles showed dark-brownish necrosis, and a huge amount of pus along the fascial planes was found. The axillary fat and antecubital fascia were also infiltrated with dark-brownish pus. The biceps, coracobrachialis, and brachialis muscles were completely ruptured and necrotized. The deltoid muscle also was partially ruptured (about 50%). Fortunately, the major neurovascular bundles, including brachial vessels, median nerve, and ulnar nerve were not involved, and the brachial artery was pulsating. So the necrotic skin, subcutaneous fat, fascia, and muscles were extensively debrided, and massive irrigation was done (Fig. 2).

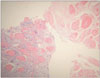

Multiple intraoperative cultures grew coagulase-positive Staphylococcus without isolation of other organisms. Histologic findings showed edematous and necrotic fascia with infiltration of polymorphonuclear cells with myonecrosis, and myositis immediately underlying the fascia (Fig. 3).

Twenty-four hours postoperatively the patient was returned to the operating room for repeat irrigation and debridement. The subcutaneous emphysema completely vanished on postoperative day 3. For the removal of remaining necrotic tissues, we performed additional debridement and irrigation 9 times in the operating room. On postoperative day 30, secondary wound closure was achieved with a local flap and split thickness skin graft. Eight months after her last operation, the patient had no fever or wound problems; only pain and limited motion of the elbow.

The patient and her family were informed and consented to her data being submitted for publication.

NF is most frequently found in immunocompromised conditions, including diabetes mellitus, malignancy, alcoholism, chronic liver disease, vascular insufficiency, organ transplantation, human immunodeficiency virus, malnutrition, and neutropenia.1) Bacterial entry for developing NF occurs as a result of some precipitating trauma laceration, cut, abrasion, contusion, burn, bite, subcutaneous injection, or operative incision that causes a break in the epidermidis.2,3) However, a few patients without obvious bacterial sources after blunt trauma may develop necrotizing fasciitis. Svensson et al.4) and Dunn5) reported that four healthy patients developed NF in contused areas of the upper extremity without direct trauma, and in bodybuilders with a biceps muscle sprain but without skin damage. Our patient was also a healthy woman who had neither external wounds such as abrasion or laceration nor a condition associated with an immunocompromised state.

A majority of cases of NF is caused by polymicrobial pathogens, even though multiple organisms may account for secondary infections. In a minority, however, only a single pathogen is involved.6,7)

Moreover, group A Streptococcus remains the most common cause of monomicrobial cases of NF, but monomicrobial infection with Staphylococcus aureus has been rarely reported. McHenry et al.6) reported monomicrobial infections in 12 of 65 patients with NF. Ten of these patients were infected with a group A Streptococcus, and two had Staphylococcus aureus infections. Brook and Frazier1) also described monomicrobial infection in 6 of 83 patients with NF. Four of these patients were infected with a group A Streptococcus, and two had Staphylococcus aureus infections. In our case, multiple intraoperative cultures grew coagulase-positive Staphylococcus as a single pathogen without a concomitant group A streptococcal infection, which showed a rapidly progressive and invasive course similar to streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis.

In conclusion, a high index of suspicion of NF, meticulous diagnosis, and early surgical intervention should be considered in minor trauma patients complaining of abrupt and exquisite pain out of proportion to injury severity.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1A radiograph taken on the second day after trauma shows subcutaneous emphysema from the left arm to the ipsilateral shoulder, neck, and lateral chest wall. |

| Fig. 2(A) An intraoperative photograph shows a severely swollen arm and brown-colored necrotic skin, and purulent pus discharge from the wound. (B) Another photograph shows necrosis of subcutaneous fat, fascia, infiltration of pus along the fascial plane, and necrosis and rupture of biceps and brachialis muscles. (C) The necrotic skin, subcutaneous fat, fascia, and muscles were extensively debrided. |

References

1. Brook I, Frazier EH. Clinical and microbiological features of necrotizing fasciitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995. 33(9):2382–2387.

2. Fildes J, Bannon MP, Barrett J. Soft-tissue infections after trauma. Surg Clin North Am. 1991. 71(2):371–384.

3. Fisher JR, Conway MJ, Takeshita RT, Sandoval MR. Necrotizing fasciitis: importance of roentgenographic studies for soft-tissue gas. JAMA. 1979. 241(8):803–806.

4. Svensson LG, Brookstone AJ, Wellsted M. Necrotizing fasciitis in contused areas. J Trauma. 1985. 25(3):260–262.

5. Dunn F. Two cases of biceps injury in bodybuilders with initially misleading presentation. Emerg Med J. 2002. 19(5):461–462.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download