Abstract

Calcific myonecrosis is a rare late post-traumatic condition, in which a single muscle is replaced by a fusiform mass with central liquefaction and peripheral calcification. Compartment syndrome is suggested to be the underlying cause. The resulting mass may expand with time due to recurrent intralesional hemorrhage into the chronic calcified mass. A diagnosis may be difficult due to the long time between the original trauma and the symptoms of calcific myonecrosis. We encountered a 53-year-old male patient diagnosed with calcific myonecrosis in the lower leg. We report the case with a review of the relevant literature.

Calcific myonecrosis is a rare disease that has been shown to be a sequelae of compartment syndrome that develops after trauma and progresses slowly over a period of several years. It has been reported to develop primarily in lower leg muscles, such as the tibialis anterior muscle, peroneus longus muscle, extensor hallucis longus, etc., and has been attributed to trauma, such as fibular fracture, tibial fracture, femoral shaft fracture accompanying ischemic symptoms, rupture of the femoral artery accompanying ischemic muscle necrosis, peripheral nerve injury (common peroneal nerve), etc.1) In calcific myonecrosis, the time of the onset of calcific myonecrosis symptoms is significantly different from the inital injury, making an ac curate diagnosis difficult. Moreover, it may be misdiagnosed as a soft tissue sarcoma due to its large size and radiological characteristic.2-4) We encountered a 53-year-old male patient diagnosed with calcific myonecrosis that developed in the lower leg. We report the case with a review of the relevant literature.

A 53-year-old male patient visited our hospital due to a huge mass in the anterior area of the left lower leg as the chief complaint. Forty four years ago, the patient was bitten by a snake and the area below the left knee joint was tied with a string and maintained for 3 months to prevent the spread of snake venom. The area below the knee joint began necrotized gradually. A mass developed with time while the left lower leg was healing gradually. Over a period of several years, the mass gradually increased in size. No special findings were detected in his past medical history, except for diabetes.

At the time of admission, the physical examination revealed a huge mass in the muscle layer along the anterior tibial muscle in the left lower leg that was palpated. However, no redness, no heating sensation or no pyrogenic reaction was detected in the vicinity. There was no tenderness around the mass. The mass was hard and fusiform shaped. The ankle joint was in an almost ankylosed state at 5° of plantar flexion, there was no abnormal sensation below the lower leg, and the blood circulation was good. The complete blood test, blood chemistry, and serum electrolyte level were normal.

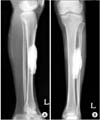

The radiograph showed well marginated radioopaque density in the parosteal area of the midshaft of the tibia (Fig. 1). The shape of the radioopaque dense material was ovoid in the longitudinal axis. The size of the mass was approximately 10 × 3 cm and there was no evidence of tibial erosion or cortical thickening. The MRI showed a dense bone forming tumor in the parosteal area of the midshaft of the tibia (Fig. 2). It showed homogenous low signal intensity on the T1, T2 weighted images and there was no evidence of medullary cavity communication or a connection stalk. There was no evidence of any significant soft tissue infiltration. Under spinal anesthesia, its resection was performed in the supine position.

The operative findings revealed the mass to be located in the anterior tibial area. It was 10 × 3 × 4 cm in size and covered with a hard fibrotic sheath. There was no connection between the mass and the adjacent bones, and the proximal and distal areas of the mass were connected by a fibrotic cord. The inside of the capsule was filled with a yellowish powder (Fig. 3).

The histological examination showed an extensive amorphous pink substance with calcific material due to necrosis of the skeletal muscle and fibrin (Fig. 4). The simple radiographs taken after surgery showed no residual mass, and the wound healed without necrosis or infection.

Calcific myonecrosis is a very rare disease. It is primarily the sequelae of compartment syndrome that developed after trauma, and tends to progress slowly over a period of several years.4,5) It was reported to develop primarily in the lower legs but some cases in the arm have been reported.6) Among the reported cases, trauma preceded its development in most cases, and the mass developed over a long time after the injury. According to several reports, it can develop over a period ranging from 10 to 64 years.1-6) In our case, it developed gradually over 40 years after the injury.

The pathophysiological mechanisms associated with these lesions are not fully understood. However, the lesions most likely results from posttraumatic ischemia. O'Keefe et al.1) suggested that an initial compartment syndrome decreases the circulation within a limited space resulting in necrosis and fibrosis. With time, the mass enlarges due to the repeated intralesional hemorrhage.7) Radiologically, the calcified mass grows along the muscles, and it shows a pattern of invasion to the entire muscles or the entire compartment. The incidence of such lesions is rare and the radiological findings reveal an aggressive pattern. Sometimes, they are misdiagnosed as soft tissue sarcomas.3,6,7) Therefore, it is important to differentiate these lesions from soft tissue sarcomas that show a calcified pattern. The treatment of calcific myonecrosis involves excision of the mass. However, several authors reported complications, such as postoperative infections in 30% of cases treated surgically.4,8,9) Hence, considerable attention needs to be paid during surgery. Viau et al.10) and Malisano and Hunter9) performed incision and drainage in two patients with anterior compartment lesion in the lower leg and left the wound open. Nevertheless, a secondary infection appeared due to the incomplete resection of the lesion, and one patient underwent a below-knee amputation. Since such a method could induce a secondary infection, chronic fistula formation, etc., it is better to treat the condition by the repeated aspiration of the mass to avoid secondary infection.

O'Keefe et al.1) performed marginal debridement, and in one patient, the surgical wound was left open after resecting the lesion. Early et al.8) reported satisfactory results in 2 patients, in whom the remaining empty space generated after complete resection of the calcified mass was filled with tibial muscles. In our case, after removing the mass, complete wound closure was performed without filling with soft tissues. Compression dressing was administered for two weeks after surgery, which prevented the generation of dead space. There were no complications, such as infections in the surgical area and fistula formation during the 3 year follow-up after surgery.

Cacific myonecrosis is a rare disease that develops as a sequelae of trauma, and is difficult to diagnose. This disease develops after injury over a long period of time. It can be observed radiologically in a single muscle or throughout a compartment, and occurs frequently in the anterior compartment. We report our experience of a patient, who developed calcific myonecrosis over a 44 year period after trauma and was treated with a marginal excision, along with a review of the relevant literature. This condition should be suspected in cases with a soft tissue mass in the same area as compartment syndrome after trauma. Moreover, the development of calcific myonecrosis can be prevented by detecting compartment syndrome early and administering the appropriate treatment.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs show a fusiform mass overlying the anterior compartment without an erosion of the tibia.

References

1. O'Keefe RJ, O'Connell JX, Temple HT, et al. Calcific myonecrosis: a late sequela to compartment syndrome of the leg. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995. (318):205–213.

2. Holobinko JN, Damron TA, Scerpella PR, Hojnowski L. Calcific myonecrosis: keys to early recognition. Skeletal Radiol. 2003. 32(1):35–40.

3. Ryu KN, Bae DK, Park YK, Lee JH. Calcific tenosynovitis associated with calcific myonecrosis of the leg: imaging features. Skeletal Radiol. 1996. 25(3):273–275.

4. Tuncay IC, Demirors H, Isiklar ZU, Agildere M, Demirhan B, Tandogan RN. Calcific myonecrosis. Int Orthop. 1999. 23(1):68–70.

5. Wang JW, Chen WJ. Calcific myonecrosis of the leg: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001. (389):185–190.

6. Larson RC, Sierra RJ, Sundaram M, Inwards C, Scully SP. Calcific myonecrosis: a unique presentation in the upper extremity. Skeletal Radiol. 2004. 33(5):306–309.

7. Zohman GL, Pierce J, Chapman MW, Greenspan A, Gandour-Edwards R. Calcific myonecrosis mimicking an invasive soft-tissue neoplasm: a case report and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998. 80(8):1193–1197.

8. Early JS, Ricketts DS, Hansen ST. Treatment of compartmental liquefaction as a late sequelae of a lower limb compartment syndrome. J Orthop Trauma. 1994. 8(5):445–448.

9. Malisano LP, Hunter GA. Liquefaction and calcification of a chronic compartment syndrome of the lower limb. J Orthop Trauma. 1992. 6(2):245–247.

10. Viau MR, Pedersen HE, Salciccioli GG, Manoli A 2nd. Ectopic calcification as a late sequela of compartment syndrome: report of two cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983. (176):178–180.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download