Abstract

Background

The purpose of our study is to evaluate the clinical results of arthroscopic suture bridge repair for patients with rotator cuff tears.

Methods

Between January 2007 and July 2007, fifty-one shoulders underwent arthroscopic suture bridge repair for full thickness rotator cuff tears. The average age at the time of surgery was 57.1 years old, and the mean follow-up period was 15.4 months.

Results

At the last follow-up, the pain at rest improved from 2.2 preoperatively to 0.23 postoperatively and the pain during motion improved from 6.3 preoperatively to 1.8 postoperatively (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively). The range of active forward flexion improved from 138.4° to 154.6°, and the muscle power improved from 4.9 kg to 6.0 kg (p = 0.04 and 0.019, respectively). The clinical results showed no significant difference according to the preoperative tear size and the extent of fatty degeneration, but imaging study showed a statistical relation between retear and fatty degeneration. The average Constant score improved from 73.2 to 83.79, and the average University of California at Los Angeles score changed from 18.2 to 29.6 with 7 excellent, 41 good and 3 poor results (p < 0.001 and p = 0.003, respectively).

Surgical rotator cuff repair is aimed at anatomic restoration of the rotator cuff and the head of humerus to reduce pain and restore the joint function. While open rotator cuff repair was commonly done in the past, arthroscopic repair is currently being widely performed. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair provides benefits that cannot be obtained with open surgery. Unfortunately, it is also known for its technical difficulty and the inevitable employment of special equipment such as suture anchors.1-3) Accordingly, arthroscopic repair had to be replaced by open surgery in some cases and mini-open surgery was the treatment of choice in other cases. However, due to the advanced development of surgical instruments and the increased experience with arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, most rotator cuff tears can now be treated arthroscopically. Furthermore, the focus of the treatment has been transferred from just treating rotator cuff tears to raising the healing rates and inventing more efficient surgical techniques. As a result, the double-row suture anchor technique was introduced, which maximizes the contact area between the tendon and the tuberosity insertion footprint, and the suture bridge technique has become a recommended treatment method.4-7) Particularly, the latter technique has been described in biomechanical studies as being more effective in increasing the contact area and the contact pressure at the tendon-bone interface and achieving high initial fixation strength compared to the former technique.4-7) Even so, there are few reported studies on the clinical results of the suture bridge technique.

The purpose of this study was to report the clinical outcomes of the arthroscopic suture bridge technique in patients with full thickness rotator cuff tear and to assess the impact of the preoperative tear size and the extent of fatty degeneration on the final outcome. We postulated that the preoperative tear size would have no impact on the final outcome due to the excellent initial fixation strength provided by the arthroscopic suture bridge technique, and even in cases of large tears. In contrast, we expected that the extent of fatty degeneration would affect the final outcome.

This retrospective review included 49 patients (51 cases) who had undergone arthroscopic suture bridge repair for a full thickness rotator cuff tear between January 2007 and July 2007. The patients with the following conditions were excluded: partial thickness rotator cuff tear, the patients who required tenotomy or tenodesis for treating the long biceps tendon, superior glenoid labrum injury that required fixation, acromioclavicular arthritis that required excision of the distal end of the clavicle, advanced glenohumeral arthritis, anterior instability of the shoulder, nerve injury and previous shoulder joint surgery. There were 25 males (27 cases) and 24 females (24 cases) with an average age of 57.1 years (range, 36 to 75 years). Thirty-nine cases involved the dominant shoulder and 12 cases involved the non-dominant shoulder. The mean follow-up period was 15.4 months (range, 12 to 18.3 months).

The size of the tear was measured along the longest axis by using probes during surgery and the tear sizes were categorized into small (< 1 cm), medium (1 cm to 3 cm), large (3 cm to 5 cm) and massive (> 5 cm) tears according to the classification of DeOrio and Cofield.8)

All of the physical examinations were performed the day before surgery and during the follow-up period. The measurements obtained at the last follow-up were used for analysis. Subjective pain was measured using the visual analogue scale (VAS). Muscle strength tests were performed using a Nottingham Mecmesin Myometer (Mecmesin Co., Nottingham, UK) and the values were recorded in kilograms (kg). Maximum elevation strength was measured with the arm elevated to 90° in the scapular plane and maximum external rotation strength and maximum internal rotation strength were measured with the arm in the neutral position. Regarding the range of motion, forward elevation, external rotation with the arm in a neutral position, external and internal rotation with the arm at 90° abduction and posterior internal rotation and abduction were all measured before surgery and at the last follow-up. For clinical assessments, the Constant score9) and the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) score were measured and the patients' satisfaction was also evaluated.

All of the operations were performed by the same surgeon with the patients in the beach-chair position. Passive range of motion and the levels of anterior, posterior and inferior translation were examined with the patient under anesthesia. After preoperative skin preparation, a posterior portal was established 2 cm inferior and 1 cm medial to the posterolateral corner of the acromion and a diagnostic arthroscopy was performed through this portal. When the presence of rotator cuff tear was identified and a lesion of the long biceps tendon was also observed, the arthroscope was inserted through the posterior portal to the subacromial space, and a lateral portal was additionally created. Through this portal, the pattern of the rotator cuff tear in the subacromial space was observed. If severe fibrillation was observed inferior to the acromion, except when the acromion was seen as being flat on the preoperative radiographs, the patient was young or the rotator cuff tear was caused by a definite trauma, then acromioplasty was performed based on the plain radiographs and arthroscopic findings. After acromioplasty, a posterolateral portal was created as a viewing portal in the middle of the imaginary line connecting the posterior portal and the lateral portal.10) A shaver was used to debride the torn edges of the rotator cuff and the greater tuberosity, and a high speed burr was used to expose the cancellous bone. The torn rotator cuff was pulled with a grasper and a proper suture site was determined. A spinal needle was inserted from the lateral edge of the acromion to determine the proper position and angle (immediately lateral to the joint cartilage) for insertion of a bone punch. Through a 5 mm incision, a Bio-Cork screw suture anchor (Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) was inserted into the planned site. The number of the anchors used was 1 or 2 depending on the tear size. Then, through the 3 sister portals10) or a modified Neviaser portal, a suture was passed through the rotator cuff as proximally as possible using a suture hook (Linvatec, Largo, FL, USA) or a Banana SutureLasso (Arthrex) and the suture limb that was loaded onto the inserted suture anchor was passed using the shuttle-relay. The suture limbs were spaced the same distance apart and Revo knots, one of the non-sliding knots, were tied in a horizontal mattress suture pattern. Suture bridge repair was then carried out by fixating one limb from each anchor to the lateral aspect of the greater tuberosity using a PushLock anchor (Arthrex). Postoperatively, a self-controlled analgesia device was used for all patients at their request.

Pendulum exercises and passive forward flexion were started immediately after surgery and passive exercise was performed until the 6th postoperative week to restore the normal range of motion. Active joint exercise and muscle strength exercise were performed from the 6th postoperative week.

The pre- and postoperative clinical outcomes were compared using paired t-tests and Wilcoxon signed rank tests. The Mann-Whitney test was used to assess differences regarding gender, age, range of motion and muscle strength in the groups, as divided according to the tear size, and the association between the preoperative Global fatty degeneration index (GFDI) and the final outcome. Correlation between the preoperative tear size and the retear rate was assessed using Pearson's chi-square test. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver.12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) with a 95% confidence interval.

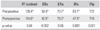

The mean VAS score at rest decreased from 2.2 (0 to 7) preoperatively to 0.23 (0 to 2.5) postoperatively (p < 0.001). The mean VAS score during motion improved from 6.3 (2 to 9) preoperatively to 1.8 (0 to 7.5) postoperatively (p < 0.001). The mean range of active forward flexion increased from 138.4° preoperatively to 154.6° postoperatively and the mean range of passive forward flexion improved from 143.4° to 161.9° (p = 0.04, 0.009). The mean external rotation in the neutral position was 50.4° preoperatively and 42.5° postoperatively (p = 0.052). The mean external rotation at 90° abduction was 70.7° preoperatively and 78.3° postoperatively and the mean internal rotation at 90° abduction was 63.4° preoperatively and 47.5° postoperatively (p = 0.06, < 0.001). The mean internal rotation behind the back was T12 preoperatively and T10 postoperatively (p = 0.021) (Table 1).

The mean muscle strength during forward flexion increased from 4.9 kg preoperatively to 6.0 kg postoperatively, during external rotation in the neutral position from 6.5 kg to 6.9 kg (p = 0.038, 0.383), and during internal rotation in the neutral position from 7.8 kg to 8.6 kg (p = 0.265). The improvement of the muscle strength during forward flexion was statistically significant.

The mean Constant score9) improved from 73.2 (range, 44 to 88) preoperatively to 83.7 (range, 20 to 99) postoperatively (p = 0.001). The mean UCLA score increased from 18.2 preoperatively to 29.7 at the last follow-up (p < 0.001) and there were 7 (13.7%) excellent, 41 (80.4%) good, and 3 (5.9%) poor cases. The mean patient satisfaction score at the last follow-up was 92.1 out of the total 100 points.

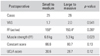

Eight (16%) small, 17 (33%) medium, 9 (18%) large and 17 (33%) massive tears that were classified according to the classification of DeOrio and Cofield8) were observed during arthroscopy. The small and medium tears were combined into one group and the large and massive tears were combined into another group, and the clinical outcomes at the last follow-up were compared between the 2 groups. The differences between the two groups regarding the preoperative age, gender, the level of pain at rest and during motion, and the muscle strength and range of motion during forward flexion did not show statistical significance (p = 0.124, 0.203, 0.673, 0.574, 0.056, and 0.903, respectively). No significant difference was found between the groups regarding the postoperative retear rate (p = 0.109). Muscle strength during forward flexion at the last follow-up was more satisfactory in the small to medium tear group than that in the large to massive tear group (p = 0.029), but no significant differences were found with regard to the other parameters (Table 2).

According to the GFDI that was evaluated preoperatively using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),11) the patients were subdivided into those with ≤ 1 GFDI (21 cases) and those with > 1 GFDI (30 cases). The postoperative pain at rest and during movement remarkably decreased in both groups (p < 0.001). No significant difference was found between the groups regarding the preoperative VAS score for pain at rest and during movement (VAS) (p = 0.143, 0.097, respectively). Postoperatively, the VAS score for pain at rest was notably low in the group with ≤ 1 GFDI (p = 0.043) (Table 3). With regard to the range of motion, active and passive forward flexion and external rotation in the neutral position were greater preoperatively in the group with ≤ 1 GFDI than that in the other group (p = 0.003, 0.003, and 0.013, respectively), but no statistically significant difference was found between the groups postoperatively (p = 0.075, 0.396, and 0.799, respectively). The muscle strength, the clinical test results and the postoperative patient satisfaction were better on average in the group with ≤ 1 GFDI both preoperatively and postoperatively, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.251, 0.198, and 0.348, respectively)

MRI scanning was performed in 46 of the 51 cases at an average of 7.2 months (range, 6 to 9 months) after surgery and retear was observed in 17 (36.9%) of them: 2 (28.6%) in the 7 patients with small tears, 4 (26.7%) in the 15 patients with medium tears, 3 (33.3%) in the 9 patients with large tears and 8 (53.3%) in the 15 patients with massive tears. The patients were divided into an anatomic restoration group and a retear group for comparisons. The Constant score9) at the last follow-up was 84.8 and 82.3 respectively and the UCLA score was 29.9 and 28.7 respectively, showing no statistically significant difference between the groups (p = 0.189, 0.273). However, a significant difference was found between the groups regarding the preoperative fatty degeneration, which was severe in the retear group (p = 0.048).

Advances have been made in performing surgical rotator cuff repair and there are many recent studies showing excellent clinical outcomes.12-15) Particularly, arthroscopy, which is associated with a good cosmetic appearance and rapid rehabilitation due to the minimal damages to adjacent structures, is employed in various medical fields. It is widely recommended for the treatment of the shoulder because there is no need to detach the deltoid muscle when performing arthroscopy.13)

The factors that appear to be determinants for retear after repair and postoperative recovery include the suture strength,4) the contact area and contact pressure at the tendon-bone interface,16) the tendon-bone interface motion,17) fatty degeneration of the rotator cuff muscles,18) the tear size, the bone quality of the humerus, the design and effect of the suture materials and the rehabilitation program's propriety. In open repairs, suture techniques with superior holding power such as the Mason-Allen technique19) and transfixion suture are employed without difficulty. However, they are not easy to perform in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair and other materials such as suture anchors should be used instead. Unfortunately, biomechanical studies have shown that the arthroscopic single-row suture anchor technique allows weaker fixation than the established transfixion suture does.17,20) The concept of footprint reconstruction was recently introduced and Apreleva et al.21) evaluated the 3-dimensional structures of the rotator cuff insertion sites after repairs using various techniques and they described that the larger the interface was, the better was the potential for tendon-bone healing and the strength of the repaired tendon. Thereafter, several arthroscopic repair techniques that provide greater holding power, interface area and contact pressure have been developed and the arthroscopic suture bridge technique is one of them.22-24) While the arthroscopic suture bridge technique has been described in many biomechanical reports as being more effective for obtaining high initial fixation strength and greater interface area and pressure than the other suture methods, studies analyzing the clinical results of such repairs are rare.6,7,25)

Regarding the factors influencing the clinical outcome of rotator cuff repair, Kim et al.1) reported that the final outcome was more dependent on the preoperative tear size rather than the surgical technique. With regard to the rotator cuff integrity and the shoulder function, some authors have documented that they could not find a clear correlation between them,22,26,27) while others suggested that great rotator cuff integrity would result in satisfying shoulder function.23,24,28,29) Gazielly et al.23) associated the anatomical integrity of the rotator cuff and the clinical outcome: the larger the early tear size was the worse the clinical outcome was. In this current study, arthroscopic suture bridge repairs for various sizes of rotator cuff tears resulted in improvement in pain, range of motion and muscle strength, and the differences in the clinical improvement, except for muscle strength during forward flexion, were not statistically significant between the small and medium size tear group and the large and massive size tear group. In addition, postoperative MRI showed no differences between the groups regarding the recurrence rate (p = 0.109). We attribute this to the anatomical integrity of the rotator cuff, which could be obtained with the arthroscopic suture bridge technique regardless of the preoperative tear size. Therefore, we believe that this clinical study confirmed the advantages of the arthroscopic suture bridge technique, and this technique has been previously established by many biomechanical studies: the firm, early fixation and high tendon-bone contact pressure provided by the repair method contributes to the repaired cuff's integrity even in the cases of large size tears.5-7,25)

Preoperative fatty degeneration is known as an important factor for the anatomical integrity of the repaired rotator cuff. According to Goutallier et al.,11) severe fatty degeneration was correlated with an unsatisfactory surgical outcome and a high retear rate. Similarly, radiological retears were identified in the patients who had severer fatty degeneration in our study. However, the retear rate and preoperative fatty degeneration were not correlated with each other at a statistically significant level for the clinical tests, which is contrary to the study of Goutallier et al.11) In our opinion, this is because the suture bridge technique was not as much affected by the level of preoperative fatty degeneration as the other methods.

In this study, we analyzed the final clinical results of the arthroscopic suture bridge technique for rotator cuff repair and we confirmed clinical improvements in the repaired shoulders regardless of the preoperative tear size and the level of fatty degeneration. However, we think that studies involving a larger population, long-term follow-up and comparisons with other suture techniques should be conducted in the future to determine the magnitude of the contribution of the technique to the integrity of the shoulder and the clinical improvement.

The arthroscopic suture bridge technique for rotator cuff repair resulted in clinical improvement in pain, the range of motion and muscle strength regardless of the preoperative tear size and fatty degeneration, although radiologically detected retears were found in the patients with severer preoperative fatty degeneration. This technique can be applied when a large tear has to be treated or when the established methods such as the single-row suture technique will not achieve satisfying results due to advanced fatty degeneration. In addition, the clinical improvement that can be obtained with this method is expected to be less affected by the tear size and fatty degeneration.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Kim SH, Ha KI, Park JH, Kang JS, Oh SK, Oh I. Arthroscopic versus mini-open salvage repair of the rotator cuff tear: outcome analysis at 2 to 6 years' follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2003. 19(7):746–754.

2. Severud EL, Ruotolo C, Abbott DD, Nottage WM. Allarthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: a long-term retrospective outcome comparison. Arthroscopy. 2003. 19(3):234–238.

3. Wilson F, Hinov V, Adams G. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff: 2- to 14-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2002. 18(2):136–144.

4. Kim DH, Elattrache NS, Tibone JE, et al. Biomechanical comparison of a single-row versus double-row suture anchor technique for rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2006. 34(3):407–414.

5. Ma CB, Comerford L, Wilson J, Puttlitz CM. Biomechanical evaluation of arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs: double-row compared with single-row fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006. 88(2):403–410.

6. Park MC, ElAttrache NS, Tibone JE, Ahmad CS, Jun BJ, Lee TQ. Part I: Footprint contact characteristics for a transosseous-equivalent rotator cuff repair technique compared with a double-row repair technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007. 16(4):461–468.

7. Park MC, Tibone JE, ElAttrache NS, Ahmad CS, Jun BJ, Lee TQ. Part II: biomechanical assessment for a footprint-restoring transosseous-equivalent rotator cuff repair technique compared with a double-row repair technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007. 16(4):469–476.

8. DeOrio JK, Cofield RH. Results of a second attempt at surgical repair of a failed initial rotator-cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984. 66(4):563–567.

9. Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987. (214):160–164.

10. Rhee YG, Vishvanathan T, Thailoo BK, Rojpornpradit T, Lim CT. The "3 Sister Portals" for arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007. 8(2):53–57.

11. Goutallier D, Postel JM, Gleyze P, Leguilloux P, Van Driessche S. Influence of cuff muscle fatty degeneration on anatomic and functional outcomes after simple suture of full-thickness tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003. 12(6):550–554.

12. Bennett WF. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness supraspinatus tears (small-to-medium): a prospective study with 2- to 4-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2003. 19(3):249–256.

13. Gartsman GM, Khan M, Hammerman SM. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998. 80(6):832–840.

14. Jones CK, Savoie FH 3rd. Arthroscopic repair of large and massive rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2003. 19(6):564–571.

15. Murray TF Jr, Lajtai G, Mileski RM, Snyder SJ. Arthroscopic repair of medium to large full-thickness rotator cuff tears: outcome at 2- to 6-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002. 11(1):19–24.

16. Park MC, Cadet ER, Levine WN, Bigliani LU, Ahmad CS. Tendon-to-bone pressure distributions at a repaired rotator cuff footprint using transosseous suture and suture anchor fixation techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2005. 33(8):1154–1159.

17. Ahmad CS, Stewart AM, Izquierdo R, Bigliani LU. Tendon-bone interface motion in transosseous suture and suture anchor rotator cuff repair techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2005. 33(11):1667–1671.

18. Goutallier D, Postel JM, Bernageau J, Lavau L, Voisin MC. Fatty muscle degeneration in cuff ruptures: pre- and postoperative evaluation by CT scan. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994. (304):78–83.

19. Mason ML, Allen HS. The rate of healing of tendons: an experimental study of tensile strength. Ann Surg. 1941. 113(3):424–459.

20. Cummins CA, Appleyard RC, Strickland S, Haen PS, Chen S, Murrell GA. Rotator cuff repair: an ex vivo analysis of suture anchor repair techniques on initial load to failure. Arthroscopy. 2005. 21(10):1236–1241.

21. Apreleva M, Ozbaydar M, Fitzgibbons PG, Warner JJ. Rotator cuff tears: the effect of the reconstruction method on three-dimensional repair site area. Arthroscopy. 2002. 18(5):519–526.

22. Galatz LM, Ball CM, Teefey SA, Middleton WD, Yamaguchi K. The outcome and repair integrity of completely arthroscopically repaired large and massive rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004. 86(2):219–224.

23. Gazielly DF, Gleyze P, Montagnon C. Functional and anatomical results after rotator cuff repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994. (304):43–53.

24. Harryman DT 2nd, Mack LA, Wang KY, Jackins SE, Richardson ML, Matsen FA 3rd. Repairs of the rotator cuff: correlation of functional results with integrity of the cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991. 73(7):982–989.

25. Cole BJ, ElAttrache NS, Anbari A. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs: an anatomic and biomechanical rationale for different suture-anchor repair configurations. Arthroscopy. 2007. 23(6):662–669.

26. Jost B, Pfirrmann CW, Gerber C, Switzerland Z. Clinical outcome after structural failure of rotator cuff repairs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000. 82(3):304–314.

27. Liu SH, Baker CL. Arthroscopically assisted rotator cuff repair: correlation of functional results with integrity of the cuff. Arthroscopy. 1994. 10(1):54–60.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download