Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of alendronate on bone mineral density (BMD) and to determine the persistency and side effects of alendronate treatment after hip fractures.

Materials and Methods

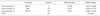

452 patients who underwent surgery for hip fractures from March 2000 to February 2007 were retrospectively included. The hip fractures consisted of 218 cases of femur neck fractures and 234 cases of intertrochanteric fractures. There were 254 women and 198 men with a mean age of 73.4 years (range: 60~95 years) at the time of surgery. The BMD was assessed in 398 patients and 348 were diagnosed with osteoporosis, while 102 received alendronate for treatment. The persistency with alendronate treatment and change of the BMD were evaluated annually. We also evaluated the side effects and reasons for discontinuation.

Results

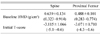

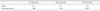

The prescription rate of alendronate was 29.3% and the persistency rate over 1 year was 33%. The annual BMD of the lumbar spine showed a 9.11% increase the first year, a 4.5% increase the second year and a 3.5% increase the third year, while negative changes were noted in the proximal femur as a 1.89% decrease the first year, a 1.38% decrease the second year and a 0.97% decrease the third year. The BMD changes were 11%(L: Lumbar spine) and 1.1%(F: Femur) for the T-scores <-4.0, 6.3%(L) and 0.9%(F) for the T-scores -3.0~-4.0, and 3.8%(L) and -3.5%(F) for the T-scores >-3.0, respectively. The BMD changes in the patients with femur neck fractures and who were treated with hemiarthroplasty were 15.6%(L) and -3.9%(F). The BMD changes in the patients with intertrochanteric hip fractures and who were treated with compression hip screws or hemiarthroplasty were 18.7%(L), 0.77%(F), 24.2%(L) and 1.19%(F), respectively. Gastrointestinal problems(19.1%) were the most common cause for discontinuation of alendronate.

Conclusion

It is important for doctors to approach osteoporosis more carefully and educate patients to follow the prescriptions in order to improve the low prescription and persistency rates for the management of osteoporotic hip fractures. Administration of alendronate may have a positive influence on the BMD of the proximal femur by lowering the rate of decreased BMD more than would be expected.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Center JR, Nguyen TV, Schneider D, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA. Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet. 1999. 353:878–882.

2. Randell AG, Nguyen TV, Bhalerao N, Silverman SL, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA. Deterioration in quality of life following hip fracture: a prospective study. Osteoporos Int. 2000. 11:460–466.

3. van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Does a fracture at one site predict later fractures at other sites? A British cohort study. Osteoporos Int. 2002. 13:624–629.

4. Colón-Emeric C, Kuchibhatla M, Pieper C, et al. The contribution of hip fracture to risk of subsequent fractures: data from two longitudinal studies. Osteoporos Int. 2003. 14:879–883.

5. Lönnroos E, Kautiainen H, Karppi P, Hartikainen S, Kiviranta I, Sulkava R. Incidence of second hip fractures. A population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2007. 18:1279–1285.

6. Berry SD, Samelson EJ, Hannan MT, et al. Second hip fracture in older men and women: the Framingham Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007. 167:1971–1976.

7. Riggs BL, Melton LJ 3rd. The worldwide problem of osteoporosis: insights afforded by epidemiology. Bone. 1995. 17:5 Suppl. 505S–511S.

8. Reginster JY, Bruyere O, Audran M, et al. The Group for the Respect of Ethics and Excellence in Science. Do estrogens effectively prevent osteoporosis-related fractures? Calcif Tissue Int. 2000. 67:191–194.

9. Bellantonio S, Fortinsky R, Prestwood K. How well are community-living women treated for osteoporosis after hip fracture? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001. 49:1197–1204.

10. Recker RR, Gallagher R, MacCosbe PE. Effect of dosing frequency on bisphosphonate medication adherence in a large longitudinal cohort of women. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005. 80:856–861.

11. Cramer JA, Amonkar MM, Hebborn A, Altman R. Compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate dosing regimens among women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005. 21:1453–1460.

12. Lyles KW, Colón-Emeric CS, Magaziner JS, et al. Zoledronic acid and clinical fractures and mortality after hip fracture. N Engl J Med. 2007. 357:1799–1809.

13. Orimo H, Sugioka Y, Fukunaga H, et al. Diagnostic criteria of primary osteoporosis. Osteoporos Jpn. 1996. 4:643–643.

15. Cranney A, Guyatt G, Griffith L, Wells G, Tugwell P, Rosen C. Meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. IX: Summary of meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Rev. 2002. 23:570–578.

16. Schnitzer T, Bone HG, Crepaldi G, et al. Alendronate Once-Weekly Study Group. Therapeutic equivalence of alendronate 70 mg once-weekly and alendronate 10 mg daily in the treatment of osteoporosis. Aging. 2000. 12:1–12.

17. Freedman KB, Kaplan FS, Bilker WB, Strom BL, Lowe RA. Treatment of osteoporosis: are physicians missing an opportunity? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000. 82-A:1063–1070.

18. Rabenda V, Mertens R, Fabri V, et al. Adherence to bisphosphonates therapy and hip fracture risk in osteoporotic women. Osteoporos Int. 2008. 19:811–818.

19. Rietbrock S, Olson M, van Staa TP. The potential effects on fracture outcomes of improvements in persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates. QJM. 2009. 102:35–42.

20. Harrington JT, Broy SB, Derosa AM, Licata AA, Shewmon DA. Hip fracture patients are not treated for osteoporosis: a call to action. Arthritis Rheum. 2002. 47:651–654.

21. Heaney RP, Yates AJ, Santora AC 2nd. Bisphosphonate effects and the bone remodeling transient. J Bone Miner Res. 1997. 12:1143–1151.

22. Ravn P, Weiss SR, Rodriguez-Portales JA, et al. Alendronate Osteoporosis Prevention Study Group. Alendronate in early postmenopausal women: effects on bone mass during long-term treatment and after withdrawal. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000. 85:1492–1497.

23. Chesnut CH 3rd, McClung MR, Ensrud KE, et al. Alendronate treatment of the postmenopausal osteoporosis woman: effect of multiple dosage on bone mass and bone remodeling. AM J Med. 1995. 99:144–152.

24. Reginster JY, Adami S, Lakatos P, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of once-monthly oral ibandronate in postmenopausal osteoporosis: 2 year results from the MOBILE study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006. 65:654–661.

25. Bone HG, Hosking D, Devogelaer JP, et al. Ten years' experience with alendronate for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2004. 350:1189–1199.

26. Magnusson HI, Lindén C, Obrant KJ, Johnell O, Karlsson MK. Bone mass changes in weight-loaded and unloaded skeletal regions following a fracture of the hip. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001. 69:78–83.

27. van der Poest Clement E, van Engeland M, Ader H, Roos JC, Patka P, Lips P. Alendronate in the prevention of bone loss after a fracture of the lower leg. J Bone Miner Res. 2002. 17:2247–2255.

28. Weinreb M, Rodan GA, Thompson DD. Osteopenia in the immobilized rat hind limb is associated with increased bone resorption and decreased bone formation. Bone. 1989. 10:187–194.

29. Pocock NA, Eisman JA, Yeates MG, Sambrook PN, Eberl S. Physical fitness is a major determinant of femoral neck and lumbar spine bone mineral density. J Clin Invest. 1986. 78:618–621.

30. Pocock NA, Eisman JA, Hopper JL, Yeates MG, Sambrook PN, Eberl S. Genetic determinants of bone mass in adults. A twin study. J Clin Invest. 1987. 80:706–710.

31. Cecilia D, Jódar E, Fernández C, Resines C, Hawkins F. Effect of alendronate in elderly patients after low trauma hip fracture repair. Osteoporos Int. 2009. 20:903–910.

32. Cramer JA, Silverman S. Persistence with bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis: finding the root of the problem. Am J Med. 2006. 119:4 Suppl 1. S12–S17.

33. Hamilton B, McCoy K, Taggart H. Tolerability and compliance with risedronate in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int. 2003. 14:259–262.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download