Abstract

Background and Purpose

The importance of health-related quality of life (HrQoL) has been increasingly emphasized when assessing and providing treatment to patients with chronic, progressive, degenerative disorders. The 39-item Parkinson's disease questionnaire (PDQ-39) is the most widely used patient-reporting scale to assess HrQoL in Parkinson's disease (PD). This study evaluated the validity and reliability of the translated Korean version of the PDQ-39 (K-PDQ-39).

Methods

One hundred and two participants with PD from 10 movement disorder clinics at university-affiliated hospitals in South Korea completed the K-PDQ-39. All of the participants were also tested using the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE), Korean version of the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale (K-MADS), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) and non-motor symptoms scale (NMSS). Retests of the K-PDQ-39 were performed over time intervals from 10 to 14 days in order to assess test-retest reliability.

Results

Each K-PDQ-39 domain showed correlations with the summary index scores (rS=0.559-0.793, p<0.001). Six out of eight domains met the acceptable standard of reliability (Cronbach's α coefficient ≥0.70). The Guttman split-half coefficient value of the K-PDQ-39 summary index, which is an indicator of test-retest reliability, was 0.919 (p<0.001). All of the clinical variables examined except for age, comprising disease duration, levodopa equivalent dose, modified Hoehn and Yahr stage (H&Y stage), UPDRS part I, II and III, mood status (K-MADS), cognition (K-MMSE), daytime sleepiness (ESS) and (NMSS) showed strong correlations with the K-PDQ-39 summary index (p<0.01).

Parkinson's disease (PD), which is both chronic and progressive, is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder, and its prevalence is increasing rapidly.1,2 Health-related quality of life (HrQoL) is considered critical in chronically ill patients, especially in the elderly, and PD research is increasingly focused on factors affecting the HrQoL.3 Although motor features have until recently dominated clinical impact assessments in patients with PD, non-motor symptoms are currently attracting more attention as determinants of HrQoL in PD,4,5 with a growing emphasis on the importance of HrQoL issues when initiating and maintaining treatment.5,6

The 39-item Parkinson's disease questionnaire (PDQ-39), which contains 39 items involving 8 discrete dimensions that mainly evaluate HrQoL, is the representative disease-specific tool for assessing HrQoL in PD. The PDQ-39 evaluates mobility, activities of daily living, emotional well-being, stigma, social support, cognition, communication, bodily discomfort and summary index.7,8 The PDQ-39 was originally developed in Britain and has been translated into and validated in many different languages worldwide.9-13 Because perceptions of HrQoL are subjective and may vary according to cultural and individual backgrounds, translated and validated versions tailored for different cultural contexts are required for research.

The aim of the present study was to translate the PDQ-39 into Korean and to validate the reliability and consistency of the new Korean version as well as its feasibility for use in future assessments of HrQoL in the Korean-speaking PD population.

One hundred and two PD patients from 10 movement-disorder centers at university-affiliated hospitals in South Korea who met the clinical diagnostic criteria of the United Kingdom Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank14 were enrolled in the present study. The obligatory inclusion criterion for all participants was no change in anti-parkinsonian drugs for at least the previous 4 weeks. The exclusion criteria included patients who were younger than 40 years at the onset of PD, had possible secondary causes of PD such as drugs or structural brain lesions that can induce parkinsonism, who were taking medications including antidepressants that could affect cognitive function, or had impaired cognitive function represented by a total Mini-Mental State Examination score of less than 24. All subjects provided written informed consent for unprompted study participation. Ethical approval was obtained from the joint ethics committee of each participating university hospital.

The original PDQ-39 was translated into Korean using forward and backward translation, expert committee review and pretests of the translated Korean version of the PDQ-39 (K-PDQ-39). Two independent bilingual translators translated the original British version of the PDQ-39 into Korean. The translated Korean version was then translated back into British English by another bilingual translator who had no knowledge of the original version of the questionnaire. The back-translated version was then compared to the original version by the same translators. An expert committee (comprising D.Y. Kwon, J.S. Baik and S.B. Koh) reviewed the translated version and modified the draft version until a consensus was reached among them. After pretesting the translated version in four patients, the K-PDQ-39 was finalized and used in subsequent analyses.

The K-PDQ-39 comprises 39 items involving 8 discrete dimensions: mobility, activities of daily living, emotional well-being, stigma, social support, cognition, communication and bodily discomfort. The assessment period is the "previous 1 month." Each item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 ("never") to 4 ("always"). The total K-PDQ-39 score is expressed as a percentage ranging from 0 to 100.

All of the authors, who were experts in movement disorders and experienced interviewers from each movement center, conducted the following assessments of subjects in order to assess and qualify non-motor symptoms in PD patients and K-PDQ-39: basic demographics, levodopa equivalent dose (LDED),15 modified Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) stage,16 Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) parts I, II, and III,17 the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE)18 for measuring cognitive function, the Korean version of the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale (K-MADS), the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS),19 and the non-motor symptoms scale (NMSS).20 Participants returned to outpatient clinics for retests using the K-PDQ-39 in order to assess test-retest reliability over time intervals of from 10 to 14 days, which was a sufficient delay to minimize memory or practice effects.

Reliability was assessed in order to measure the internal consistency and stability. Floor and ceiling effects involving less than 20% of the total population per domain were considered acceptable.35 Cronbach's α coefficient was calculated to analyze the internal consistency. The criterion value for α was ≥0.70. Test-retest reliability was assessed using the Guttman Split-Half Coefficient analyses with values higher than 0.70 considered indicative of acceptable reliability. The relationships between subscales of the K-PDQ-39 and other variables were analyzed using Spearman's rank correlation coefficients, since scores were not evenly distributed. These coefficients were also used to quantify the convergent validity with other clinical scales. SPSS (version 15.0 for Windows, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

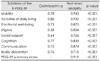

A total of 102 patients (52 men and 50 women) were recruited for the study. The demographic data are listed in Table 1. Among the 102 PD patients, 75 (73.5%) patients had H&Y stages up to 2.0 (32 at stage 1, 12 at stage 1.5, and 31 at stage 2) and 27 (26.5%) had H&Y stages of at least 2.5 (17 at stage 2.5, 9 at stage 3, 1 at stage 4). Finally, 101 PD patients completed the K-PDQ-39 retest.

Table 2 lists the scores in each domain and the total score. The mean total summary index of the K-PDQ-39 was 23.20±18.63% (mean±SD), and ranged from 0% to 74.9%. A higher score in each K-PDQ-39 domain indicates greater discomfort felt by the patient: emotional well-being (27.51±24.11%) and bodily discomfort (26.43±23.38%) were the major complaints, while social support (14.70±21.47%) and communication (13.05±18.49%) were the least problematic. All of the K-PDQ-39 domains showed acceptable ceiling effects. Emotional well-being and cognition domains were within the acceptable range of floor effects (<20%), but the other six domains ranged from 21.6% to 52.9%. Both the floor and ceiling effects of the SI were 0% (Table 2).

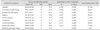

Each K-PDQ-39 domain showed significant correlations with summary index scores (rS=0.559-0.793, p<0.001). Six of the eight domains met the standards of reliability (Cronbach's α coefficient ≥0.70); the exceptions were stigma and social support (Table 3). For assessments of test-retest reliability, the Guttman Split-Half Coefficient value of the K-PDQ-39 summary index was 0.919 (p<0.001). and ranged between 0.715 and 0.943 for the eight domains, which satisfied the standards for test-retest reliability (p<0.001) (Table 3).

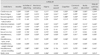

The relationships of the K-PDQ-39 and clinical data with rating scales were analyzed. All clinical variables except age, disease duration, LDED, H&Y stage, UPDRS parts I, II, and III, mood status (K-MADS), cognition (K-MMSE) and daytime sleepiness (ESS) showed strong correlations with the K-PDQ-39 summary index (p<0.01). Age was the only factor that was not significantly correlated with the K-PDQ-39 domains; the other factors-including disease duration, LDED, H&Y stage, UPDRS parts I, II, and III, K-MADS, K-MMSE and ESS- were significantly correlated with each K-PDQ-39 domain (p<0.01-0.05) (Table 4).

There is an increasing need to evaluate HrQoL when managing patients with chronic, degenerative diseases.3,21 We translated the most commonly used and validated instrument for evaluating HrQoL in PD patients, the PDQ-39, into Korean, and found the K-PDQ-39 to be a reliable, valid and useful instrument that was easily applicable to the Korean-speaking PD population. The data of the present study were collected from 10 different movement-disorder clinics and interviews were performed by different investigators, which strengthens the positive results of the K-PDQ-39 reliability and validity in terms of suitability for application in clinical practice.

The mean scores in the domains were lower (indicating a lower degree of discomfort) than the results for the original British and other translated, and validated versions, including those in Chinese, Greek, Spanish, American English and Portuguese.7-13,22 A possible explanation for this result is that the disease severity according to H&Y stage being milder and the stages of PD being earlier in the present study than in the patients included in previous studies, since several studies have demonstrated that mean PDQ-39 scores are positively correlated with disease duration as well as disease severity.8,11,12 Additionally, disease duration and severity primarily contribute to HrQoL through associated motor complications arising from treatment in late-stage PD.23-25 However, the scores were lowest for social support and communication, as also found in the present study.10-12 These findings are also reflected in the presence of floor effects in over half of the domains, with no ceiling effects in any of the domains. Social support, communication and stigma domains showed the largest floor effects in this study, which is similar to previous validation studies involving various languages.8,13,34 A cut-off above 0.70 for Cronbach's α coefficient is reportedly considered indicative of acceptable internal consistency and reliability.26 The internal consistency of the K-PDQ-39 was satisfactory, since Cronbach's α coefficient ranged from 0.58 to 0.80. Two of the eight domains failed to reach the standards, and the average correlations of the items comprising the test were very strong (Cronbach's α coefficient=0.913). Test-retest reliability as calculated by the Guttman Split-Half coefficient value was also adequate, with values ranging from 0.715 to 0.943. These results suggest that the K-PDQ-39 is a stable and reliable tool.

The relationship between clinical data and K-PDQ-39 was also analyzed. While disease duration, disease severity (H&Y stage and UPDRS), LDED, depressive mood (K-MADS), cognition (K-MMSE), and daytime sleepiness (ESS) were strongly correlated with K-PDQ-39 domains, age was only strongly correlated with the K-PDQ-39 mobility domain. These results, which are consistent with those of previous studies27,28 may be accounted for by several factors. First, patient age has no direct relationship with disease duration or severity, both of which have strong correlations with PD HrQoL.8,11,12 Second, the age range of the participants in the present study was limited to43-84 years (with a mean of 65.3 years), which Soh et al.21 pointed out restricts the ability of HrQoL to discriminate between diverse age groups. Our data also suggest that a longer and more severe case of PD will lower the quality of life. UPDRS (parts I and II) scores were strongly correlated with all items of the K-PDQ-39. The scores for depressive mood and cognition were closely related to nearly all items of the K-PDQ-39, indicating that HrQoL factors are associated with both motor and non-motor symptoms of PD. In particular, the mood status of the patients (as assessed by K-MADS) showed the strongest correlations with all domains of K-PDQ-39 (rS=0.425-0.704, p<0.01). Similar patterns have been found previously, in that the the presence of depressive symptoms was the main factor associated with a poor quality of life.3,29 Concurrently, NMSS items that quantify non-motor symptoms of PD demonstrated strong correlations with K-PDQ-39 scores, which implies that non-motor features of PD are the most important determinants of quality of life in PD.4,5 Although non-motor symptoms are prevalent from the early stages or prestages of motor symptoms of PD, the clinical impact of non-motor aspects on HrQoL has only recently been highlighted.21,30-33

The first limitation of the present study was the uneven distribution of disease severity, with most participants having mild disease (73.5% of the participants had an H&Y stage of up to 2.0). The late-stage HrQoL of the PD patients therefore might not have been properly evaluated. However, the present study did not aim to assess HrQoL severities in patients, and also showed that the HrQoL had clinical impacts from the relatively early, mild stages of PD. The second limitation of the present study was that other assessments of HrQoL were not compared with the K-PDQ-39, and hence convergent validity might not have been verified.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the K-PDQ-39 is a useful, valid, and reliable instrument for assessing HrQoL in PD patients. Further detailed investigations of HrQoL in Korean-speaking PD patients should be undertaken using the K-PDQ-39.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Correlation analysis of K-NMSS total score and K-PDQ-39. K-NMSS: Korean version-non-motor symptoms scale for Parkinson's disease, K-PDQ: Korean version-Parkinson's disease questionnaire.

Table 3

Internal consistency (Cronbach's α coefficient) between subitem scores and the summary index score and test-retest reliability (Guttman Split-Half coefficient) of the K-PDQ-39 (n=102)

Table 4

Spearman's correlation of the K-PDQ-39 and clinical features and rating scales

*Spearman's rank correlation, p<0.01, †Spearman's rank correlation, p<0.05.

ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale, H&Y stage: Hoehn and Yahr stage, K-PDQ: Korean version-Parkinson's disease questionnaire, LDED: levodopa equivalent dose, MADS: Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale, MMSE: Mini-Mental Status Examination, NMSS: the non-motor symptoms scale for Parkinson's disease, PD: Parkinson's disease, UPDRS: the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale.

References

1. Saunders CD. Parkinson's Disease: A New Hope. 2000. Boston, MA: Harvard Health Publications.

2. Marttila RJ, Rinne UK. Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease in Finland. Acta Neurol Scand. 1976. 53:81–102.

3. Den Oudsten BL, Van Heck GL, De Vries J. Quality of life and related concepts in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review. Mov Disord. 2007. 22:1528–1537.

4. Martinez-Martin P, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Kurtis MM, Chaudhuri KR. NMSS Validation Group. The impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related quality of life of patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2011. 26:399–406.

5. Qin Z, Zhang L, Sun F, Fang X, Meng C, Tanner C, et al. Health related quality of life in early Parkinson's disease: impact of motor and non-motor symptoms, results from Chinese levodopa exposed cohort. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009. 15:767–771.

6. Uitti RJ. Treatment of Parkinson's disease: focus on quality of life issues. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012. 18:Suppl 1. S34–S36.

7. Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Peto V, Greenhall R, Hyman N. The Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39): development and validation of a Parkinson's disease summary index score. Age Ageing. 1997. 26:353–357.

8. Peto V, Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Greenhall R. The development and validation of a short measure of functioning and well being for individuals with Parkinson's disease. Qual Life Res. 1995. 4:241–248.

9. Bushnell DM, Martin ML. Quality of life and Parkinson's disease: translation and validation of the US Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39). Qual Life Res. 1999. 8:345–350.

10. Martínez-Martín P, Frades Payo B. The Grupo Centro for Study of Movement Disorders. Quality of life in Parkinson's disease: validation study of the PDQ-39 Spanish version. J Neurol. 1998. 245:Suppl 1. S34–S38.

11. Tsang KL, Chi I, Ho SL, Lou VW, Lee TM, Chu LW. Translation and validation of the standard Chinese version of PDQ-39: a quality-of-life measure for patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2002. 17:1036–1040.

12. Katsarou Z, Bostantjopoulou S, Peto V, Alevriadou A, Kiosseoglou G. Quality of life in Parkinson's disease: Greek translation and validation of the Parkinson's disease questionnaire (PDQ-39). Qual Life Res. 2001. 10:159–163.

13. Luo W, Gui XH, Wang B, Zhang WY, Ouyang ZY, Guo Y, et al. Validity and reliability testing of the Chinese (mainland) version of the 39-item Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39). J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2010. 11:531–538.

14. Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Lees AJ. The clinical features of Parkinson's disease in 100 histologically proven cases. Adv Neurol. 1993. 60:595–599.

15. Langston JW, Widner H, Goetz CG, Brooks D, Fahn S, Freeman T, et al. Core assessment program for intracerebral transplantations (CAPIT). Mov Disord. 1992. 7:2–13.

17. Movement Disorder Society Task Force on Rating Scales for Parkinson's Disease. The Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS): status and recommendations. Mov Disord. 2003. 18:738–750.

18. Kang Y, Na DL, Hahn S. A validity study on the Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 1997. 15:300–308.

19. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991. 14:540–545.

20. Chaudhuri KR, Martinez-Martin P, Brown RG, Sethi K, Stocchi F, Odin P, et al. The metric properties of a novel non-motor symptoms scale for Parkinson's disease: Results from an international pilot study. Mov Disord. 2007. 22:1901–1911.

21. Soh SE, Morris ME, McGinley JL. Determinants of health-related quality of life in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011. 17:1–9.

22. Carod-Artal FJ, Martinez-Martin P, Vargas AP. Independent validation of SCOPA-psychosocial and metric properties of the PDQ-39 Brazilian version. Mov Disord. 2007. 22:91–98.

23. Chapuis S, Ouchchane L, Metz O, Gerbaud L, Durif F. Impact of the motor complications of Parkinson's disease on the quality of life. Mov Disord. 2005. 20:224–230.

24. Chrischilles EA, Rubenstein LM, Voelker MD, Wallace RB, Rodnitzky RL. Linking clinical variables to health-related quality of life in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2002. 8:199–209.

25. Gómez-Esteban JC, Zarranz JJ, Lezcano E, Tijero B, Luna A, Velasco F, et al. Influence of motor symptoms upon the quality of life of patients with Parkinson's disease. Eur Neurol. 2007. 57:161–165.

26. Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951. 16:297–334.

27. Schrag A, Jahanshahi M, Quinn N. What contributes to quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000. 69:308–312.

28. Schrag A, Selai C, Mathias C, Low P, Hobart J, Brady N, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in MSA: the MSA-QoL. Mov Disord. 2007. 22:2332–2338.

29. Schrag A. Quality of life and depression in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Sci. 2006. 248:151–157.

30. Muslimovic D, Post B, Speelman JD, Schmand B, de Haan RJ. CARPA Study Group. Determinants of disability and quality of life in mild to moderate Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008. 70:2241–2247.

31. Qin Z, Zhang L, Sun F, Liu H, Fang X, Chan P, et al. Depressive symptoms impacting on health-related quality of life in early Parkinson's disease: results from Chinese L-dopa exposed cohort. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2009. 111:733–737.

32. Rahman S, Griffin HJ, Quinn NP, Jahanshahi M. Quality of life in Parkinson's disease: the relative importance of the symptoms. Mov Disord. 2008. 23:1428–1434.

33. Winter Y, von Campenhausen S, Gasser J, Seppi K, Reese JP, Pfeiffer KP, et al. Social and clinical determinants of quality of life in Parkinson's disease in Austria: a cohort study. J Neurol. 2010. 257:638–645.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download