Abstract

Background

Human infection with Streptococcus suis (S. suis), a zoonotic pathogen, has been reported mainly in pig-rearing and pork-consuming countries. Meningitis is the most-common clinical manifestation and is often associated with deafness and vestibular dysfunction.

Case Report

A 57-year-old man was referred to the hospital with headaches, fevers, chills, and hearing impairment. Meningitis was confirmed and S. suis was isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid. Spondylodiscitis occurred after 2 weeks of antibiotic treatment, and was successfully treated with a prolonged course of antibiotics for another 4 weeks. His hearing loss was irreversible despite the improvement of other symptoms.

Streptococcus suis (S. suis), a Gram-positive facultative anaerobe, is a major porcine pathogen that can be transmitted to humans by close contact with pigs.1 Meningitis is the most-common presentation of S. suis infection, followed by sepsis, which has a higher mortality rate, particularly for splenectomized patients. Other clinical manifestations include enteritis, endocarditis, arthritis, endophthalmitis, uveitis, and spondylodiscitis.2,3 Permanent hearing loss or vestibular dysfunction are commonly occurring sequelae of S. suis infection, especially in patients with meningitis.2

Since the first described human case of S. suis infection in Denmark in 1968,4 more than 700 cases have been reported worldwide.5 The association between human infection and contact with pigs has been noted since the discovery of the disease,6 and most of the reported human S. suis cases originate from southeast Asia, which is characterized by a high density of pigs and the consumption of uncooked or lightly cooked pig products. Pig farming and consuming pig products are also common in Korea, but there have been no reports of human infection with S. suis. The present report is the first human case of S. suis infection in Korea. Distinctive complications of meningitis are also presented and discussed.

A 57-year-old, previously healthy man suffered from fevers, chills, and abdominal pain for 5 days. Examination at a local hospital revealed hearing impairment and an increased C-reactive protein level. He was referred to our hospital for the treatment of a persistent fever, headaches, hearing impairment, and dizziness. The medical history was nonspecific, except that he had reared pigs for several years until 2 years previously. At the time of admission, he had a body temperature of 36.9℃, a pulse rate of 68 beats/min, a blood pressure of 140/80 mm Hg, and a respiration rate of 20/min. A physical examination revealed neck stiffness and signs of meningeal irritation. Neither a cardiac murmur nor skin abnormalities were noted. A neurological examination revealed a drowsy mental status and hearing impairment. No other focal neurologic signs were noted.

Routine laboratory tests showed a leukocyte count of 8.3×103/mm3 with 67.4% neutrophils, a platelet count of 100×103/mm3, and a C-reactive protein level of 15.4 mg/dL. Serologic tests for syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus were negative. Blood was drawn for culture. An enhanced brain computed-tomography scan showed no abnormal findings. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) had a slight turbid color, a high opening pressure (250 mmH2O), an increased leukocyte count (380/mm3: neutrophils, 25%; lymphocytes, 25%; and monocytes, 50%), an increased protein level (86 mg/dL), and a decreased glucose level (CSF glucose, 21 mg/dL; blood glucose, 129 mg/dL). Gram staining, acid-fast bacillus staining, KOH mount, India ink preparation, and tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction of CSF were negative. The blood cultures were also negative.

The CSF culture grew small alpha-hemolytic colonies on blood agar plates. The organisms, which were Gram-positive cocci in chains, were catalase-negative and were identified as S. suis by the VITEK 2 Gram-positive card system (BioMérieux). The strain was sensitive to penicillin, ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, nitrofurantoin, imipenem, teicoplanin, and vancomycin.

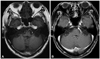

Before isolating S. suis, vancomycin and cefotaxime were started for the treatment of bacterial meningitis. A steroid injection was added to help resolve the meningeal inflammation and hearing impairment. The patient's consciousness and meningitis symptoms gradually improved, but the hearing impairment and dizziness did not. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed 3 days after admission revealed no abnormalities of the inner ear or brain parenchyma (Fig. 1). Audiometry carried out 6 and 14 days after admission revealed bilateral moderate-to-severe sensorineural hearing loss, especially in the high-frequency range. After completion of a 14-day course of antibiotic therapy, his symptoms - with the exception of hearing loss and dizziness - were improved. A follow-up CSF examination showed improved pleocytosis (leukocyte count, 9/mm3).

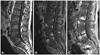

The patient complained of lower-back pain on the 20th day of admission. A physical examination revealed knocking tenderness in the lumbar area. Lumbar spine MRI revealed spondylodiscitis (Fig. 2A). The CSF parameters were as follows: leukocyte count, 13/mm3; protein level, 49 mg/dL; and glucose level, 55 mg/dL (blood glucose, 129 mg/dL). Ceftriaxone was given intravenously under the impression of a relapse, but this aggravated the back pain. Follow-up lumbar spine MRI performed 1 week later showed progression of the spondylodiscitis (Fig. 2B). Staining and culture of a tissue specimen obtained from the lumbar inflammation area revealed only inflammation. Ceftriaxone was changed to ampicillin plus sulbactam, which results in the back pain gradually subsiding. The patient was discharged in a stable condition after completion of a 4-week course of antibiotic therapy. The lower-back pain had completely resolved 1 month after discharge, but his hearing loss persisted.

This is the first report of human infection with S. suis in Korea. Human S. suis infection is usually - but not always - acquired through occupational or household exposure to contaminated pigs or pig meat.5 The proportion of S. suis meningitis patients with a history of pig exposure was 41% in Thailand3 and 33% in Vietnam.7 In addition to pigs, S. suis can be isolated from ruminants, cats, dogs, and horses.5 The patient described herein had a history of rearing pigs for several years, but he had not been in close contact with pigs or other animals for the previous 2 years. He had no other known predisposing factors, such as asplenia, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, malignancy, or structural heart disease.2 Although most reports are sporadic cases of infection, like our case, an outbreak of S. suis infection did occur in Sichuan Province, China between July and August 2005.8 The clinical course of patients in that outbreak was more fulminant than in previous reports, and 38 of the 215 affected patients died.

Meningitis is the most-common clinical manifestation of S. suis infection,5 and the presenting features of meningitis are generally similar to those of other types of bacterial pyogenic meningitis. Little is known about how S. suis invades the host and how it crosses the blood-brain barrier, but sepsis is known to be the second-most-common manifestation and a major cause of S.-suis-related death.8 S. suis was identified in the CSF in our patient, but not in repeated blood cultures. Furthermore, he had no signs of sepsis. In a previous report of S. suis meningitis, the pathogen was isolated from the CSF in 66.7% of the cases, from blood in 50%, and from both the CSF and blood in 25%.3 Early hearing impairment and vestibular dysfunction are characteristic features in patients with S. suis meningitis.2 Hearing loss is usually sensorineural, occurring in the high-frequency range,5 and causes deafness in more than one-half of patients, as in our case.2 Hemorrhagic labyrinthitis, which is evident on MRI, was recently suggested as the cause of deafness in patients with S. suis meningitis.9 However, we could not find any signal changes in the cochlea or vestibule on MRI in our patient. Thus, we believe that hemorrhagic labyrinthitis is not a unique pathogenic characteristic of deafness in S. suis meningitis. Spondylodiscitis is also one of the less-common manifestations, and some patients need surgery for its treatment.5,7,10 Spondylodiscitis in our patient occurred somewhat later than did the meningitis and hearing loss, and it was successfully treated with antibiotics (no surgery was required).

Previous work has shown that S. suis is susceptible to penicillin, ceftriaxone, and vancomycin.11 The treatment principles of S. suis meningitis are the same as those for other causes of bacterial meningitis.5 The meningitis symptoms in our patient initially responded well to cefotaxime and vancomycin. Spondylodiscitis occurred after the completion of 2 weeks of treatment, and it responded not to ceftriaxone but to prolonged treatment with ampicillin plus sulbactam. Some patients with S. suis meningitis described in previous reports have experienced relapse after 2 weeks of treatment with penicillin or ceftriaxone. Such cases of relapse occurred within 1 week of antibiotic cessation and responded to prolonged treatment for 4-6 weeks.3,5,12 Clinicians should be aware that the treatment recommendations may not be successful for all patients and may therefore need to be individually tailored.

While S. suis can be cultured from CSF or blood samples with the aid of standard microbiological techniques, it is often misidentified or even undiagnosed.13 In patients presenting with meningitis, S. suis should be considered regardless of the patient's occupational background if the characteristic features of prominent and early hearing loss are present. Moreover, increased awareness among clinicians and appropriate education of people who handle pigs or pork-derived products are needed so that they appreciate the importance of S. suis as a human pathogen.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Brain MRI of the patient. Axial T1-weighted (A) and gadolinium-enhanced (B) images showing no abnormalities in the inner ear and brain parenchyma.

Fig. 2

Lumbar spine MRI of the patient. Sagittal T1-weighted (A) and gadolinium-enhanced (B) images show irregular, patchy, marrow signal changes and gadolinium enhancement with erosive change of vertebral endplates and mild anterior paraspinal inflammatory soft-tissue thickening at the 4th and 5th lumbar vertebral bodies. The follow-up sagittal T1-weighted gadolinium-enhanced image (C) revealed progression of the same lesion.

References

1. Perch B, Kristjansen P, Skadhauge K. Group R streptococci pathogenic for man. Two cases of meningitis and one fatal case of sepsis. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1968. 74:69–76.

2. Wertheim HF, Nghia HD, Taylor W, Schultsz C. Streptococcus suis: an emerging human pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 2009. 48:617–625.

3. Suankratay C, Intalapaporn P, Nunthapisud P, Arunyingmongkol K, Wilde H. Streptococcus suis meningitis in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2004. 35:868–876.

4. Perch B, Kjemes E. Group R streptococci in man. Group R streptococci as aetiological agent in a case of purulent meningitis. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand B Microbiol Immunol. 1971. 79:549–550.

5. Huang YT, Teng LJ, Ho SW, Hsueh PR. Streptococcus suis infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2005. 38:306–313.

6. Lun ZR, Wang QP, Chen XG, Li AX, Zhu XQ. Streptococcus suis: an emerging zoonotic pathogen. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007. 7:201–209.

7. Mai NT, Hoa NT, Nga TV, Linh le D, Chau TT, Sinh DX, et al. Streptococcus suis meningitis in adults in Vietnam. Clin Infect Dis. 2008. 46:659–667.

8. World Health Organization. Outbreak associated with Streptococcus suis in pigs, China. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2005. 80:269–270.

9. Gottschalk M. Porcine Streptococcus suis strains as potential sources of infections in humans: an underdiagnosed problem in North America? J Swine health Prod. 2004. 12:197–199.

10. Poggenborg R, Gaïni S, Kjaeldgaard P, Christensen JJ. Streptococcus suis: meningitis, spondylodiscitis and bacteraemia with a serotype 14 strain. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008. 40:346–349.

11. Gottschalk M, Segura M, Xu J. Streptococcus suis infections in humans: the Chinese experience and the situation in North America. Anim Health Res Rev. 2007. 8:29–45.

12. Tan JH, Yeh BI, Seet CS. Deafness due to haemorrhagic labyrinthitis and a review of relapses in Streptococcus suis meningitis. Singapore Med J. 2010. 51:e30–e33.

13. Tsai HC, Lee SS, Wann SR, Huang TS, Chen YS, Liu YC. Streptococcus suis meningitis with ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection and spondylodiscitis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005. 104:948–950.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download