Introduction

Stroke can occur at any time and hence efficient stroke care should be provided on a 24/7/365 (hours per day/days per week/days per year) basis. However, limited human and structural resources do not always ensure consistent stroke care in real-world practice. Reflecting the concerns about care variation, several studies demonstrated that weekend admission of patients with ischemic stroke was associated with a higher mortality or poor clinical outcomes than weekday admission.

1-

4 The limited availability of staff with stroke expertise,

5 the decreased likelihood of delivering thrombolytic therapy, and the long duration of waiting for admission

6 have been suggested as possible explanations for this weekend effect. However, other studies have not found that weekend admission is significantly associated with a higher mortality after stroke

7,

8 or a decreased probability of thrombolytic therapy.

9,

10 These inconsistent results may arise from the evaluation of different settings of medical care.

The stroke care system varies substantially across countries, and so the weekend effect should be examined at the individual country level. The aim of this study was to determine the weekend effect on multiple indicators of clinical outcome for patients with acute ischemic stroke in Korea, using the prospectively collected Complications in Acute Stroke Study (COMPASS) registry.

11

Methods

Data source

We extracted relevant data from the COMPASS registry for this study. The COMPASS was a multicenter, prospective, observational study that was designed to evaluate the impact of poststroke complications on stroke outcome, and enrolled all consecutive patients with acute ischemic stroke within 7 days from onset who were admitted to four university hospitals with a neurology training program in Korea between September 1, 2004 and August 31, 2005. Patients with transient ischemic attack were excluded. Additional details of the experimental design have been published elsewhere.

11

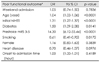

Data on each patient were collected prospectively using a predetermined protocol, including baseline demographics, risk factors, comorbid conditions, prestroke functional status as determined by the score on the modified Rankin Scale (mRS), onset-to-admission interval, initial stroke severity at admission, as measured on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), stroke subtypes using the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke (TOAST) classification, neurological and me-dical complications, and 3-month mRS outcomes. The 3-month mRS outcomes were evaluated by trained research nurses using a structured format, and were available for 1233 patients (98.3%; 66.3% obtained by direct interview and 32.0% by telephone interview). The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions.

Patient group

Patients admitted on Saturday, Sunday, and Korean national holidays were assigned to the weekend group, and the other patients were assigned to the weekday group.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was poor functional outcome as determined by mRS score of 3-6 at 3 months. We also assessed the 3-month mortality, frequency of thrombolytic therapy delivered, complications during hospitalization, and length of hospital stay as secondary outcomes.

Statistical analysis

We compared the patient characteristics and outcomes using chi-square or Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables, and the t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. The distributions of weekday and weekend admissions among the four participating hospitals were analyzed using the chi-square test. To adjust for confounders, multiple logistic regression was used to compare poor functional outcome at 3 mon-ths, 3-month mortality, and complication rate. ANCOVA was used to compare the length of hospitalization the between weekday and weekend groups. Covariates were selected for entry into multivariate analysis models based on the results of univariate analyses (p<0.1) and judgments of clinical significance. Odds ratio and 95% CI values are provided. In addition, we performed a shift analysis to compare the overall mRS distributions between the weekday and weekend groups.

Discussion

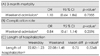

The findings of the current study show that admission on weekends for patients with ischemic stroke was associated with neither an increased risk of poor functional outcome nor an increased mortality at 3 months. In addition to the dichotomized analyses used conventionally in stroke outcome analysis, a shift analysis evaluating the overall mRS range distributions and more finely discriminating outcome differences also confirmed that the functional outcome did not differ between the weekend and weekday groups. These findings, which suggest that consistent stroke care was delivered on both weekdays and weekends, were further supported by the complication rates, frequency of thrombolysis administration, and length of hospitalization being comparable in the weekend and weekday groups.

Our findings contrast with previous studies demonstrating an association between weekend hospitalization and poor outcomes. In a prospective study of 1134 stroke patients recruited in 10 Japanese centers,

1 weekend admission was an independent predictor of poor outcome and fatality. Lower staff levels and the inaccessibility of rehabilitative services on weekends were suggested as contributing factors. Supporting the care variations between weekdays and weekends, data from the 2004 National Stroke Audit, which surveyed 246 hospitals in the United Kingdom, demonstrated that stroke patients admitted on weekends tended to have a longer delay in stroke unit admission and were less likely to have a brain scan within 24 hours.

6 Contrary to those findings, a study using the North Carolina Collaborative Stroke Registry, which was included in the Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry, showed that the CT scan time from hospital arrival was delayed in patients with weekday admission compared to those with weekend admission.

12 These results might be due to the difference of medical service-providing system between individual countries.

On the other hand, in the Canadian Stroke Network Registry study, despite the similar provision of stroke care as indicated by stroke unit admission, frequency of neuroimaging, and dysphagia screening, the 7-day stroke mortality was higher with weekend admission than with weekday admission.

6 It was thought that the proportion of severe strokes was greater in the weekend group than in the weekday group, and that this was likely to be at least partly responsible for the higher mortality found in the weekend group, even after adjusting for covariates. To adjust for the baseline imbalance of stroke severity the authors used a dichotomization with an arbitrary threshold rather than full stroke severity scales. Therefore, the baseline stroke severity might not have been fully adjusted for the 7-day mortality outcome analysis. In the current study, since full scales of the NIHSS score were included in the multivariate models, the baseline stroke severity would be more finely adjusted in comparing functional outcomes.

Our results are consistent with several studies that have demonstrated the absence of a weekend effect. In a German prospective, hospital-based stroke registry study enrolling 37396 stroke patients between 2003 and 2006, outcome and mortality did not differ between patients admitted during out-of-office hours (weekends or nighttime) and those admitted during office hours after adjustment for clinical state and admission latency.

9 Another study analyzing 599087 patients enrolled in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample Database in the United States also found no differences in in-hospital mortality or discharge disposition between weekday and weekend admissions.

10 Our findings extend these previous studies by further including analyses of the overall functional outcome distributions and other relevant indicators of complication rates and length of hospitalization, in addition to poor functional outcome and mortality. A recently published study using the Myocardial Infarction Data Acquisition System records from New Jersey hospitals showed that the 90-day mortality was higher in patients with ischemic stroke admitted to primary stroke centers or nonstroke centers on weekends, but not in patients admitted to comprehensive stroke centers.

13 In the current study, the participating centers were university hospitals with a neurology training program and a high volume of stroke patients. The facilities were staffed by neurology residents 24/7/365, and stro-ke neurologists and neurointerventionalists were on call and available at all times, and had their own critical pathways for acute ischemic stroke; these factors enabled them to provide consistent stroke care. The elements that are considered to be the key factors for comprehensive stroke centers could explain the similar results.

Contrary to prevailing concerns, the current study showed that patients presenting on weekends had a nonsignificant, higher rate of receiving thrombolysis. This might be attributed to a more severe stroke and a faster arrival on weekends, but would indicate the absence of variation in providing emergency stroke care. The present finding is in line with the results of multiple previous studies showing that patients admitted on weekends or in nonoffice hours were more likely to receive thrombolytics.

8-

10,

14 However, despite the higher thrombolysis rates on weekends, the clinical outcomes of the weekend group were not better than those of the weekday group in either our study or previous studies. Shortage of services other than thrombolysis, such as rehabilitative therapy and general medical care, might offset the benefit from the higher use of thrombolytic therapy in patients with weekend admission. However, more importantly, this discrepancy might be attributable to the small volume of thrombolysis, which would be insufficient to alter the overall outcome of patients.

This study was subject to several limitations. First, the sample was smaller than in previous studies,

1,

4,

6,

7,

14,

15 and hence the statistical power of our study would be weaker for detecting outcome differences between weekend and weekday admissions and poor clinical outcomes. However, since all of the indicators of outcome and performance disclosed universally consistent findings, the chances of a beta error, the probability of concluding that no difference between two groups exists when, in fact, there is a difference, would be small. Second, this study exclusively enrolled ischemic stroke patients and was performed at university hospitals where specialized stroke care was available 24/7/365, which might limit the generalizability of our results. Third, we did not measure other indicators of care quality such as admission-to-brain-imaging time, time to assessment of rehabilitation, intensity of rehabilitation therapy, and availability of patient education. Therefore, we did not fully explore the care consistency.

In conclusion, we found no weekend effect among patients with acute ischemic stroke presenting to neurology-training university hospitals in Korea. This putative weekend effect should be examined further to assess the nationwide acute stroke care consistency using a wider range of hospital settings and including hemorrhagic stroke.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download