A 55-year-old man presented with a 3-week history of fever and night sweats followed by the sudden onset of odd behavior. He bumped into tables and chairs, was unable to reach out for a cup of coffee that was put in front of him, and noticed friends and family only when they talked to him. Despite the fact that he had obviously lost his sight and needed assistance in all activities of daily living, he did not complain. He denied being blind and came up with excuses whenever confronted with his handicap. He did not hesitate to describe details in his environment that apparently did not exist.

The examination revealed a systolic murmur and subungual splinter hemorrhages in all fingers (

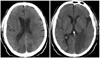

Fig. 1). Transesophageal echocardiography revealed aortic valve vegetations. A diagnosis of infective endocarditis was made and empirical antibiotic treatment started. Despite various attempts, the infective agent could not be identified. Computed tomography of the brain revealed infarction of both occipital lobes and the subcortical white matter of the left parietal lobe (

Fig. 2). Anticoagulants were withheld due to the risk of cerebral hemorrhage from mycotic aneurysms. The patient received an aortic valvular prosthesis, and there were no further episodes of cerebral embolism. Within 2 weeks of the surgery, the patient gradually realized that he was blind, but remained rather unconcerned. He was not able to regain independence despite prolonged rehabilitation.

The life of Gabriel Anton (1858-1933)

Gabriel Anton (July 28, 1858-January 3, 1933)(

Fig. 3) was an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist, born in Saaz, Bohemia. His early professional work was performed in Prague (1882), Vienna (1887), Innsbruck (1891), and Graz (1894). In 1899 Anton described the syndrome that later came to bear his name.

1 In 1905 he succeeded Carl Wernicke as chairperson of the Department of Psychiatry and Nervous Diseases in Halle, Germany. Anton worked together with many outstanding neuroscientists, including Theodor Meynert (1833-1892; Meynert's basal nucleus), Hans Chiari (1851-1916; Chiari malformation), and Arnold Pick (1851-1924; Pick's dementia). In 1908, together with Fritz Gustav von Bramann, Anton developed the "Balkenstich" procedure, where cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was drained from the lateral ventricles by punctur-ing the corpus callosum.

5 In 1917 Anton and Viktor Schmieden proposed suboccipital puncture as another method of decreasing intracranial pressure by establishing CSF outflow through an incision of the atlanto-occipital membrane.

6 Anton also made important contributions to the understanding of the basal ganglia.

7 In addition, he established free public institutions for mentally retarded children in Graz, Austria, and Halle, Germany. Anton was "a man of sensitive modesty [...] who enjoyed the admiration and friendship of his colleagues and students. [He was] an exemplary warm-hearted physician. Never would a patient leave him without some words of comfort."

8

Politically, Anton was a nationalist, a "true German."

8 In a speech given 1925 at the University of Halle, Anton referred to France as the "land of the enemy" and complained that "the worst intellectual epidemic the world has seen [...] is the hate against the German people."

9 He continued, "All our ambitions, our hopes and worries are united in the concern for the fatherland-and hereby we mean the entire and undivided fatherland."

9 (On June 28, 1919, at the end of World War I, Germany had signed the Treaty of Versailles and thereby lost several of its European territories, including large parts of Prussia, Alsace, Lorraine, and Silesia.) However, it should be noted that there is no evidence that Anton was an anti-Semite.

As stated in an obituary from 1933, Anton "bravely pursu-ed the restoration and welfare of the German race."

8 Already in 1915, when eugenics and racial hygiene were rarely debat-ed in Austria and Germany, Anton publicly advocated "superior breeding" (German, Höherzüchtung) and "selection" in order to "build a brave and noble race."

10 Like many scientists of his time, he believed that racial hygiene was a scientific method of improving society.

10,

11 In 1925, during his speech in Halle, Anton gave a detailed account of eugenics: "In light of present knowledge, it is no longer reasonable to passively follow the hereditary decline of entire families and the here-ditary inferiority and diseases as in an ancient Greek tragedy. [...] The successful individual"s frequent performance at the highest level demands a mental concentration, a sacrifice also in a physical sense, which is often detrimental to the activities of reproduction. [The result is] a constant self-eradication of the successful individual. [We have to] take precautions in order to protect and improve [...] the quality of the race. [...] It should be our directive that [the physician"s] service to the race is also the service to the individual and vice versa."

9

Although Anton did not explicitly encourage euthanasia, his choice of words concerning the means of eugenics is open to interpretation: "One might admit that the sometimes cruel eradication of inferior forms by nature is not always applicable in mankind, but there are now means and reasons to combat at least the eradication and self-eradication of the competent and productive individual."

9

The phenomenon of physicians openly advocating eugenics and racial hygiene was widespread in the Weimar Republic, and indeed reached far beyond the German-speaking co-untries. Heinrich Lundborg (1868-1943; Unverricht-Lundborg disease) in Sweden and William Gordon Lennox (1884-1960; Lennox-Gastaut syndrome) in the USA are other examples of racial hygienists honored by neurological eponyms. The elitist ideas of Anton and his contemporary neuroscientists fitted well with the ideology of the Nazis.

12 Four weeks after Anton"s death, on January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler was appoint-ed Chancellor of Germany; 6 months later the Nazi regime implemented the 'Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring" that prescribed compulsory sterilization for people with diseases such as schizophrenia, epilepsy, and Huntington"s chorea. This was soon followed by the Action T4 and other National Socialist euthanasia programs, during which physicians supervised the killing of thousands of children and adults with mental diseases.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download