Abstract

Background and Purpose

Levetiracetam (LEV) is a new antiepileptic drug that has been found to be effective as an adjunctive therapy for uncontrolled partial seizures. However, the results of several studies suggested that LEV has negative psychotropic effects, including irritability, aggressiveness, suicidality, and mood disorders. We investigated the impact of adjunctive LEV on psychiatric symptoms and quality of life (QOL) in patients with drug-refractory epilepsy (DRE) and determined the risk factors provoking psychiatric adverse events.

Methods

A 24-week, prospective, open-label study was conducted. At enrollment, we interviewed patients and reviewed their medical charts to collect demographic and clinical information. They were asked to complete self-report health questionnaires designed to measure various psychiatric symptoms and QOL at enrollment and 24 weeks later.

Results

Seventy-one patients were included in the study, 12 patients (16.9%) of whom discontinued LEV therapy due to serious adverse events including suicidality. The risk factor for premature withdrawal was a previous history of psychiatric diseases (odds ratio 4.59; 95% confidence interval, 1.22-17.32). LEV intake resulted in significant improvements in Beck Anxiety Inventory score (p<0.01) and some domains of the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised, such as somatization (p<0.05), obsessive-compulsiveness (p<0.05), depression (p<0.05), and anxiety (p<0.05). These improvements were not related to the occurrence of seizure freedom. The Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-31 overall score and subscale scores, such as seizure worry (p<0.01), overall QOL (p<0.05), emotional well-being (p<0.05), energy-fatigue (p<0.05), and social function (p<0.05), also improved.

The impact of psychiatric problems in people with epilepsy (PWE) has been neglected for a long time. However, recent studies have demonstrated that comorbid psychiatric disorders, and especially depression, can impair the quality of life (QOL), increase the suicidal risk, and affect the cost and use of medical services.1-3 Psychopathology in PWE has a multifactorial etiology including patient-related, epilepsy-related, and antiepileptic drug (AED)-related factors.4 Drug-refractory epilepsy (DRE), which is thought to be the most serious epileptic event accompanying uncontrolled seizures despite adequate trials of AEDs,5 elicits significant psychiatric problems including increased suicidal risk6 and develops poor QOL.1,7 AEDs are also associated with several mood and behavior problems due to the mechanisms of action underlying their antiepileptic activity. AEDs can be divided into two categories according to their psychotropic properties:8 i) sedating or GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid)ergic drugs and ii) activating or antiglutamatergic drugs. This classification is straightforward, but can only partly explain the psychiatric adverse events of AEDs, which are also associated with indirect mechanisms due to their interaction with the underlying epileptic process.4

Levetiracetam (LEV) is a new AED that has been found to be effective as adjunctive therapy for uncontrolled partial seizures with and without secondary generalization.9,10 LEV was introduced into the South Korean market in January 2007, and approved as an add-on therapy for partial seizures. LEV has a favorable pharmacokinetic profile and a low incidence of adverse events or interactions with other AEDs.11 Central nerve system (CNS)-related adverse events such as somnolence, lethargy, dizziness, headache, and tiredness were common, but also transient and dose-related.9,10 Since the mechanism underlying the action of LEV is unique and related to modulation of synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A,12 its precise psychotropic effect has not been elucidated. Preclinical studies using animal models of depression, anxiety, and mania have provided evidence for LEV as a mood stabilizer.13 In a systematic review using a human trial database, the incidence of behavioral adverse events was lower for LEV than those reported for some other AEDs, despite the relative higher frequency compared with placebo.14 Adjunctive LEV therapy in patients with DRE had a more favorable psychiatric impact than an add-on pregabalin in a comparative short-term study.15 An uncontrolled stu-dy found that depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with DRE were significantly improved in a 3-months add-on trial of LEV.16 In an open-label multicenter study, LEV mono- and add-on therapy possibly contributed to improve psychiatric symptoms such as interpersonal sensitivity and paranoid ideation, while simultaneously reducing seizure frequency, ultimately ameliorating QOL.17

Despite the favorable outcomes of LEV in PWE, several studies have suggested that this drug has negative psychotropic effects, including irritability, aggressiveness, suicidality, mood disorders, and other psychiatric symptoms in both children and adult patients.18-26 The risk factors of the development of psychiatric adverse events were poor seizure control, mental retardation, organic psychosyndrome, impulsivity, previous psychiatric or febrile convulsion history, and familial predisposition.19,22,23 Comorbid psychiatric symptoms in PWE are known to be the strongest predictor of QOL, irrespective of seizure control,1 and theses symptoms can sometimes push patients towards suicidal behavior.21,26 It is therefore very important to determine the psychotropic effects of AEDs, regardless of their excellent efficacy on seizure control, to prevent them from provoking harmful effects. Unfortunately, no previous studies have evaluated the psychotropic effects of LEV in Korean PWE. Thus, we investigated the psychotropic effects of LEV in patients with DRE, who are more likely to have psychiatric problems and a poor QOL than those who are seizure free, and elucidated the risk factors for provoking psychiatric adverse events.

This study included consecutive PWE who took AEDs and attended our epilepsy clinic from February 1, 2009, to June 30, 2010. We selected patients who had DRE, which was defined as a failure of adequate trials of two AEDs, at least one seizure per month for 18 months, and no seizure-free periods longer than 3 months.27 We excluded patients younger than 18 years, those who had undergone epilepsy surgery, and those with severe medical and psychiatric disorders, mental retardation (Korean Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IQ <70),28 or alcohol or drug abuse who were unable to undergo various psychometric tests and QOL measurement.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Kyungpook National University Hospital. At enrollment, all subjects gave their informed consent to participate, and were then asked to complete reliable and validated self-reported health questionnaires, including psychometric tests such as the Korean versions of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),29 Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI),30 Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R),31 Scale for Suicide Ideation-Beck (SSI-Beck),32 and Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-31 (QOLIE-31).33 Each patient was interviewed by trained epilepto-logists (S.P. and J.L.), who also reviewed the medical charts to collect demographic and clinical information into the computerized database. Information collected included seizure type, age at onset, duration and etiology of the epilepsy, duration of AED intake, number of AEDs, concurrent medical illnesses, history of febrile convulsion, family history of epilepsy, and MRI abnormalities. The etiology of epilepsy was determined by the clinical history, neurological examination, and electroencephalography and MRI findings.

A 24-week, prospective, open-label study was conducted to evaluate the psychotropic effect of LEV in patients with DRE. The study consisted of a 12-week baseline phase, followed by a 4-week titration phase and then a 20-week maintenance ph-ase. We added LEV to each patient's current AED regimen. Patients were asked to visit every 2 weeks during the first 4 weeks after the LEV intake, and then every 4 weeks thereafter. We titrated LEV as follows: 250 mg twice daily for the first 2 weeks, and 500 mg twice daily (an initial target dose) for the third and fourth weeks. Thereafter, the dose regimens were adjusted individually based on the investigator's clinical judgment regarding the patient's clinical response and tolerability, to obtain the best seizure control and tolerability. The LEV dosage was titrated up to 3,000 mg/day if the attacks had not subsided. Patients were given the opportunity to discontinue treatment if they wanted to drop out of the study due to the lack of efficacy or intolerable adverse events, or if their physicians observed serious adverse events related to LEV.

The dose of other AEDs must have been stable for 12 weeks prior to entry and remained stable throughout the study. Additional medication could be prescribed for the well-being of the patients; however, medications (other than AEDs) affecting CNS were avoided unless the patient had been on a stable dose for at least the previous 6-months before entry into the study. Concomitant medication remained at the same stable dose throughout the study. Seizure occurrence was recorded at baseline and on completion of the study. The frequency of adverse events was assessed through patient perceptions and clinical observations at 4 and 24 weeks after the initiation of the study.

We initially examined the risk factors of premature withdrawal from the study due to serious adverse events by comparing demographic and clinical variables between patients with premature withdrawal and those who completed the study. Psychometric tests and QOLIE-31 scores were evaluated at baseline and on completion of the study. We investigated differences in these measurements between pre- and post-LEV trials to investigate the psychotropic effects of LEV and to determine the impact of LEV on QOL. If negative psychotropic effects were observed, we also determined the risk factors thereof.

Efficacy end points were based on the frequency of seizures during the final 12 weeks of treatment compared with the 12 weeks baseline period. The primary efficacy variables were the incidence of ≥50% and ≥75% reduction in seizure frequency during the treatment period compared with baseline seizure frequency, and seizure freedom, defined as a 100% reduction in seizure frequency. Seizure frequency was obtained from self-reported seizure diaries and physician's query. At each visit, the investigator classified the reported seizures according to the criteria of the Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy.34

Information regarding adverse events was identified at each visit using a nonstructured interview and by clinical observation. An adverse event was defined as any diagnosis or symptom that occurred during the treatment period, regardless of its relationship to LEV. We evaluated adverse events twice, at 4 and 24 weeks, and compared the frequency of adverse events between theses two epochs.

The BDI is the most commonly used self-rating scale for depression.29 It comprises 21 items, each of which is scored on a scale of 0-3 according to how the patient feels at the current time. The BAI is a 21-item self-reported measure of anxiety severity,30 wherein the respondent is asked to rate how much he or she has been bothered by each symptom during the previous week. The answers are also scored on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3. The Cronbach's α coefficients were 0.89 for BDI and 0.91 for BAI.

The SCL-90-R is a self-rated scale that has 9 psychiatric symptom domains, comprising 90 items with a rating scale with 5 degrees of severity.31 The psychiatric domains evaluated are somatization (α=0.72), obsessive-compulsiveness (α=0.83), interpersonal sensitivity (α=0.84), depression (α=0.89), anxiety (α=0.86), hostility (α=0.68), phobic anxiety (α=0.81), paranoid ideation (α=0.69), and psychoticism (α=0.67). The SCL-90-R index and symptom-scale scores are represented as T-scores, with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. Higher T-scores reflect a greater number and/or severity of a patient's self-reported symptoms.

The SSI-Beck is a 19-item, self-reported measure designed to evaluate the current severity of a patient's specific attitudes, behaviors, and plans to commit suicide.32 The items are rated on a 3-point scale from 0 to 2. The total score can range from 0 to 38, with higher scores indicating more intense levels of suicidal ideation. The Cronbach's α coefficients were 0.87.

The QOLIE-31 is a 31-item, self-administered questionnaire designed specifically to measure the QOL of PWE.33 It consists of the subscales of seizure worry, overall QOL, emotional well-being, energy-fatigue, cognitive functioning, medication effects, and social functioning. An overall score for the seven subscales was also calculated. Higher QOLIE-31 scores are indicative of a better QOL. The Korean version of the QOLIE-31 has a Cronbach's α ranging from 0.69 to 0.86.

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 17.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics are presented as counts, percentages, and mean±standard deviation values. We used the independent t-test or Fisher's exact test to compare different groups. We calculated the odds ratio to measure the strength of any association between two binary data values. Paired t-test was used to investigate differences in SCL-90-R and QOLIE-31 scores between baseline and the completion of the study. We applied the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to measure differences in the BDI, BAI, and SSI-Beck scores between baseline and the completion of the study. The Mann-Whitney test and independent t-test was applied to compare the mean differences in the psychometric tests scores between patients with seizure freedom and those without. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

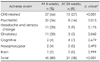

One hundred and twenty PWE who met the criteria of DRE consecutively visited our epilepsy clinic. Among them, 49 patients were excluded because they were younger than 18 years old (n=4), were mentally retarded (n=27), refused to enroll (n=10), suffered from major depressive disorders (n=2), serious cardiac problems (n=1), systemic cancer (n=1), or chronic alcoholism (n=1), or had undergone epilepsy surgery (n=3), Ultimately, 71 patients (59.2% of the original cohort) were included in the study. The demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients are summarized in Table 1. Their mean age was 35.4 years, the mean age at onset was 21.8 years, the mean duration of epilepsy was 13.6 years, and the mean number of seizures during the 12-week baseline period was 14.3. Almost all of the patients had partial seizures, and temporal lobe epilepsy was the predominant epileptic syndrome. A previous history of psychiatric diseases was noted in 26 of the 71 patients (36.6%). Twelve patients had been treated for major depressive disorders, 8 for general anxiety disorders, 6 for dysthymia, 3 for social phobia, 2 for agoraphobia, 2 for obsessive-compulsive disorder, 2 for adjustment disorder, 1 for hypochondriasis, 1 for personality disorder, and 1 for panic disorder. Nine patients (35%) suffered from at least two psychiatric diseases. The mean duration of AEDs intake was 10.6 years, and the mean number of AEDs at the baseline period was 1.9. The most commonly used AED at baseline was carbamazepine (44%), followed by lamotrigine (37%), oxcarbazepine (27%), topiramate (27%), valproate (17%), zonisamide (10%), Phenobarbital (8%), clonazepam (6%), phe-nytoin (6%), gabapentin (4%), and vigabatrin (1%).

Of the 71 enrolled patients, 56 (78.9%) completed the study. Fifteen discontinued the study due to adverse events (n=12) or a lack of efficacy (n=3). The mean daily dose of LEV at 24 weeks was 2017.9 mg (ranging from 1,000 to 3,000 mg).

At the end of the 24 weeks of LEV treatment, 18 of the 56 patients (32.1%) had achieved seizure freedom. A reduction in seizure frequency of at least 75% was noted in 22 of the 56 patients (39.3%), and a reduction of at least 50% was manifested in 33 (58.9%). The mean daily dose of LEV inducing seizure freedom, which occurred at 6 weeks after the initiation of LEV was 1,208 mg/day.

Twelve patients (16.9%) discontinued LEV due to serious adverse events within 4 weeks of commencing the medication. These adverse events were CNS-related symptoms (n=8), headache or other pains (n=6), psychiatric symptoms (n=5), gastrointestinal problems (n=5), memory or language problem (n=4), visual problems (n=2), and skin rash (n=1). Psychiatric symptoms related to premature withdrawal were nervousness, irritability, anxiety, hostility, depression, and suicidal ideation or attempt. Two patients felt an uncontrollable suicidal ideation and attempted suicide with a LEV intake 500 and 1,000 mg/day respectively, and one patient only felt suicidal ideation with a LEV intake 1,000 mg/day. One patient who attempted suicide was seizure free for the initial 2 weeks of medication, but the others experienced no changes in their seizure frequency. These patients concomitantly complained of CNS-related adverse events due to LEV, such as somnolence, asthenia, and memory problems, and had experienced a recent extreme stress. Their seizure type was a complex partial seizure evolving to secondary generalization. They all had a previous history of psychiatric diseases, and especially depression, but had only an intermittent, minor experience of suicidal ideation; they had never attempted suicide before being medicated with LEV. After the withdrawal of LEV, the suicidal ideation of these patients diminished within 1 week. They were transferred to the psychiatric department and administered antidepressants or lamotrigine. The risk factors for the premature discontinuation of LEV due to adverse events are listed in Table 2. With the exception of a previous history of psychiatric diseases, the demographic and clinical variables did not different between the patients who prematurely discontinued LEV medication and those who completed the study. The odds ratio of history of psychiatric diseases was 4.59 (95% confidence interval: 1.22-17.32).

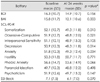

The adverse events associated with LEV in patients who completed the study are listed in Table 3. Adverse events were noted in 45 of 56 patients (80.4%) at 4 weeks after the initiation of the study, but only manifested in 21 of 56 patients (37.5%) at the end of the study. The frequency of adverse events was significantly decreased during these epochs (p<0.001, Fisher's exact test). Most of the adverse events were mild and tolerable. The most common adverse events were related to the CNS, such as somnolence, asthenia, and dizziness, followed by psychiatric problems, such as nervousness, anxiety, and hostility. These adverse events were also significantly decreased at the end of the study (p<0.01 for CNS-related side effects and p<0.05 for psychiatric problems; Fisher's exact test).

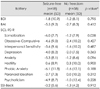

The BDI, BAI, SCL-90-R, and SSI-Beck scores are compared between baseline and the completion of the study in Table 4. There were significant improvements in BAI scores (p<0.01) and some domains of SCL-90-R, such as somatization (p<0.05), obsessive-compulsiveness (p<0.05), depression (p<0.05) and anxiety (p<0.05). None of the tests revealed significant aggravation of psychiatric symptoms after LEV intake. As shown in Table 5, the changes in psychometric test scores relative to the existence of seizure freedom were minimal, with the exception of somatization (p<0.05).

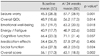

The changes in QOLIE-31 overall and subscale scores between baseline and the completion of the study are given in Table 6. The overall QOLIE-31 score was significantly increased after LEV intake (p<0.01). There were significant improvements in QOLIE-31 subscale scores, for seizure worry (p<0.01), overall QOL (p<0.05), emotional well-being (p<0.05), energy-fatigue (p<0.05), and social function (p<0.05).

This is the first study to evaluate the psychotropic effects of LEV as an add-on therapy in Korean patients with DRE. We have demonstrated that adjunctive LEV therapy in these patients not only effectively controlled their seizures, but may also have contributed to improvements in their psychiatric symptoms and QOL. LEV therapy was discontinued due to serious adverse events including suicidality by 16.9% of the patient. The risk factor for the premature withdrawal of LEV was a previous history of psychiatric diseases. Therefore, clinicians should ask their patients' psychiatric history before administering LEV to prevent the occurrence of serious adverse events related to LEV.

The superiority of the efficacy and tolerability of LEV as an add-on therapy in patients with DRE has been well documented. In a meta-analysis of four randomized placebo-controlled trials of adjunctive LEV therapy in DRE patients with partial onset, indirect comparisons of LEV with other newer AEDs manifested that LEV had a favorable responder and/or withdrawal rate relative to other AEDs with dose used in clinical trials.35 In a prospective, open-label study of adjunctive LEV therapy in 92 Korean adults with uncontrolled partial epilepsy, ≥50% and ≥75% reduction in seizure frequency were experienced by 49.5% and 34%, respectively, and seizure freedom was attained in 22.7% during the final 12-weeks.10 Our data revealed more favorable efficacies; ≥50% and ≥75% reduction in seizure frequency were experienced by 58.9% and 39.3% of the cohort, respectively, and seizure freedom was acquired in 32.1% during the same period. Regarding the tolerability of LEV, previous studies have found that at least one adverse event manifested in 64-89% of patients.9,10 A similar prevalence of adverse events was found for our patients at 4 weeks after the initiation of treatment, but the frequency was significantly decreased at the end of the study.

Despite the favorable efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive LEV therapy, 16.9% of our patients withdrew prematurely due to serious adverse events. The most common adverse event associated with discontinuation of LEV was CNS-related symptoms, followed by headache or other pains, and psychiatric or gastrointestinal problems. Psychiatric symptoms related to discontinuation of LEV, and which were manifested by 7% of our patients, were nervousness, irritability, anxiety, hostility, depression, and suicidal ideation or attempt. In placebo-controlled trials investigating the safety profile of LEV in Caucasian DRE patients, 15% of LEV-treated patients and 11.6% of placebo-treated patients either withdrew from their respective trial or required a dosage reduction.36-38 The most common causes of withdrawal from the trial in the LEV group were CNS-related symptoms such as somnolence (4.4%), dizziness (1.4%), and asthenia (1.3%). Depression and personality disorders were also reported as severe adverse events, despite the low prevalence (less than 1%). Only 4% of Korean DRE patients experienced early withdrawal of LEV, which was due to somnolence, headache, abdominal pain, and brain tumor.10 Psychiatric adverse events such as abnormal behavior, insomnia, anxiety, nervousness, and depression, leading to temporary discontinuation of LEV, occurred in 5% of patients. These results suggest that the likelihood of developing serious psychiatric adverse events related to the premature withdrawal of LEV is higher in Korean PWE than in Caucasian PWE.

We have demonstrated that the risk factor for the premature withdrawal of LEV due to adverse events in our cohort was a previous history of psychiatric diseases. Patients with psychiatric history were 4.6 times more likely to withdraw prematurely from LEV therapy than those without a psychiatric history. It is not known why LEV provokes serious adverse events in patients with psychiatric history. Furthermore, it has not been demonstrated whether this phenomenon is unique to LEV or common to many AEDs. Although a positive relationship between the psychiatric adverse events associated with LEV and a psychiatric history has been reported previously,19,22,23 this does not mean that all patients with a psychiatric history will discontinue LEV due to the development of psychiatric adverse events. Further study is warranted to clarify the relationship between the premature withdrawal of LEV and psychiatric diseases.

To the best of our knowledge, our finding of suicidality associated with a specific AED in Korean PWE is a novel one; 3 of the 71 DRE patients (4.2%) who took LEV manifested suicidality. This cannot be fully explained by forced normalization, a phenomenon whereby depressive or psychotic episodes develop in patients who become seizure free after having suffered from DRE,39 because only one patient became seizure free after the initiation of LEV. Therefore, we presume that LEV may be closely linked to the occurrence of suicidal ideation or behavior. In January 2008, the United State Food and Drug Administration issued a safety warning regarding the risk of suicidality related to AEDs,40 which summarized the results of a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled clinical trials of 11 AEDs including LEV. This showed that the risk of the development of suicidality was twice as high among patients who received AEDs as among those who received the placebo. The risk increased soon after the initiation of therapy, persisted through week to 24, and was elevated regardless of the type of AED received. Our patients also experienced suicidality in the early period of a LEV trial.

There are very few studies in which the risk of suicidality associated with AEDs has been examined. Regarding the frequency of suicidality in LEV, only 1 observational study has documented that 4 out of 517 Caucasian patients (0.7%) taking LEV reported suicidal ideation.21 The frequency of suicidality manifestation was higher in our study, which may be explained by ethnic differences in the effect of AEDs or the frequency of psychiatric histories in the study patients: only 16% of the Caucasian patients had a psychiatric history,21 whereas 37% of our patients manifested a psychiatric history. Since we have shown that the existence of a psychiatric history may be closely linked to the occurrence of psychiatric adverse events, this may explain the higher frequency of suicidality associated with LEV by our patients.

We demonstrated that at 24 weeks, adjunctive LEV therapy in DRE patients did not aggravate their psychiatric symptoms, and rather possibly contributed to improve them. Suicidal ideation also tended to decrease after LEV therapy. These results are consistent with those of previous reports.15-17 Depressive and anxiety symptoms and suicidal thoughts were improved significantly after LEV intake in an Italian study.16 Interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety and paranoid ideation among the domains of SCL-90-R after a LEV trial were ameliorated in German and Taiwanese studies.15,17 In addition, our study documented improvements in somatization and obsessive-compulsive behavior. Although all of these symptoms can be ameliorated by seizure freedom itself rather than the psychotropic effects of LEV, with the exception of somatization, we found no association between seizure freedom and improvement in psychiatric symptoms. Thus, LEV can be safely prescribed as a positive psychotropic agent provided the physician is aware of the risk factors related to premature withdrawal of LEV. A previous psychiatric history can be easily detected by simply asking patients or using screening tools to determine psychiatric symptoms.

We found that adjunctive LEV therapy significantly improved the patient's QOL. This result concurs with that of a Korean LEV add-on trial.10 QOL in PWE is known to be improved by complete seizure control.41 However, since comorbid psychiatric symptoms are known to be the strongest predictor of QOL, irrespective of seizure control,1 AEDs with a negative psychotropic profile may induce poor QOL in a seizure-free state. Therefore, we have shown herein that LEV does not have a negative psychotropic profile and may thus have a positive effect on QOL.

While our study has documented that LEV is well tolerated, with an affirmative result for psychiatric influences, it was subject to some methodological limitations. First, since this was an open-label study, we cannot exclude the possibility of a placebo effect; a placebo-controlled study is thus warranted. Second, because the SCL-90-R was not designed to evaluate anger, irritability, and aggressiveness, which have been well documented in associated with LEV intake,18,19,22-25 further study should thus be conducted to determine the attribution of LEV to those symptoms. Third, since our enrolled patients were exposed to polytherapy, we cannot exclude the effect of a drug interaction between LEV and other AEDs on their psychiatric symptoms. It has been shown that valproate, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine are mood stabilizer,42 and therefore, adding LEV to those AEDs may addictively affect the patient's psychiatric symptoms. We were unable to measure this effect statistically due to the small number of patients included in this study. Further studies enrolling larger numbers of patients are needed to elucidate the true effect of LEV on psychiatric symptoms.

Figures and Tables

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Geum-Ye Bae and Jee-Eun Jung, neuropsychologists, for supporting the completion of self-report health questionnaires.

References

1. Park SP, Song HS, Hwang YH, Lee HW, Suh CK, Kwon SH. Differential effects of seizure control and affective symptoms on quality of life in people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2010. 18:455–459.

2. Lim HW, Song HS, Hwang YH, Lee HW, Suh CK, Park SP, et al. Predictors of suicidal ideation in people with epilepsy living in Korea. J Clin Neurol. 2010. 6:81–88.

3. Cramer JA, Blum D, Fanning K, Reed M. Epilepsy Impact Project Group. The impact of comorbid depression on health resource utilization in a community sample of people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2004. 5:337–342.

4. Mula M, Monaco F. Antiepileptic drugs and psychopathology of epilepsy: an update. Epileptic Disord. 2009. 11:1–9.

5. Berg AT, Shinnar S, Levy SR, Testa FM, Smith-Rapaport S, Beckerman B. Early development of intractable epilepsy in children: a prospective study. Neurology. 2001. 56:1445–1452.

6. Nilsson L, Ahlbom A, Farahmand BY, Asberg M, Tomson T. Risk factors for suicide in epilepsy: a case control study. Epilepsia. 2002. 43:644–651.

7. Baker GA, Jacoby A, Buck D, Stalgis C, Monnet D. Quality of life of people with epilepsy: a European study. Epilepsia. 1997. 38:353–362.

8. Ketter TA, Post RM, Theodore WH. Positive and negative psychiatric effects of antiepileptic drugs in patients with seizure disorders. Neurology. 1999. 53:S53–S67.

9. Cereghino JJ, Biton V, Abou-Khalil B, Dreifuss F, Gauer LJ, Leppik I. Levetiracetam for partial seizures: results of a double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Neurology. 2000. 55:236–242.

10. Heo K, Lee BI, Yi SD, Huh K, Kim JM, Lee SA, et al. Efficacy and safety of levetiracetam as adjunctive treatment of refractory partial seizures in a multicentre open-label single-arm trial in Korean patients. Seizure. 2007. 16:402–409.

11. De Smedt T, Raedt R, Vonck K, Boon P. Levetiracetam: part II, the clinical profile of a novel anticonvulsant drug. CNS Drug Rev. 2007. 13:57–78.

12. Lynch BA, Lambeng N, Nocka K, Kensel-Hammes P, Bajjalieh SM, Matagne A, et al. The synaptic vesicle protein SV2A is the binding site for the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004. 101:9861–9866.

13. Muralidharan A, Bhagwagar Z. Potential of levetiracetam in mood disorders: a preliminary review. CNS Drugs. 2006. 20:969–979.

14. Cramer JA, De Rue K, Devinsky O, Edrich P, Trimble MR. A systematic review of the behavioral effects of levetiracetam in adults with epilepsy, cognitive disorders, or an anxiety disorder during clinical trials. Epilepsy Behav. 2003. 4:124–132.

15. Ciesielski AS, Samson S, Steinhoff BJ. Neuropsychological and psychiatric impact of add-on titration of pregabalin versus levetiracetam: a comparative short-term study. Epilepsy Behav. 2006. 9:424–431.

16. Mazza M, Martini A, Scoppetta M, Mazza S. Effect of levetiracetam on depression and anxiety in adult epileptic patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008. 32:539–543.

17. Wu T, Chen CC, Chen TC, Tseng YF, Chiang CB, Hung CC, et al. Clinical efficacy and cognitive and neuropsychological effects of levetiracetam in epilepsy: an open-label multicenter study. Epilepsy Behav. 2009. 16:468–474.

18. Hurtado B, Koepp MJ, Sander JW, Thompson PJ. The impact of levetiracetam on challenging behavior. Epilepsy Behav. 2006. 8:588–592.

19. Weintraub D, Buchsbaum R, Resor SR Jr, Hirsch LJ. Psychiatric and behavioral side effects of the newer antiepileptic drugs in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2007. 10:105–110.

20. Bootsma HP, Ricker L, Diepman L, Gehring J, Hulsman J, Lambrechts D, et al. Levetiracetam in clinical practice: long-term experience in patients with refractory epilepsy referred to a tertiary epilepsy center. Epilepsy Behav. 2007. 10:296–303.

21. Mula M, Sander JW. Suicidal ideation in epilepsy and levetiracetam therapy. Epilepsy Behav. 2007. 11:130–132.

22. Mula M, Trimble MR, Sander JW. Are psychiatric adverse events of antiepileptic drugs a unique entity? A study on topiramate and levetiracetam. Epilepsia. 2007. 48:2322–2326.

23. Helmstaedter C, Fritz NE, Kockelmann E, Kosanetzky N, Elger CE. Positive and negative psychotropic effects of levetiracetam. Epilepsy Behav. 2008. 13:535–541.

24. Labiner DM, Ettinger AB, Fakhoury TA, Chung SS, Shneker B, Tatum Iv WO, et al. Effects of lamotrigine compared with levetiracetam on anger, hostility, and total mood in patients with partial epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009. 50:434–442.

25. de la Loge C, Hunter SJ, Schiemann J, Yang H. Assessment of behavioral and emotional functioning using standardized instruments in children and adolescents with partial-onset seizures treated with adjunctive levetiracetam in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Epilepsy Behav. 2010. 18:291–298.

26. Andersohn F, Schade R, Willich SN, Garbe E. Use of antiepileptic drugs in epilepsy and the risk of self-harm or suicidal behavior. Neurology. 2010. 75:335–340.

27. Berg AT, Shinnar S, Levy SR, Testa FM, Smith-Rapaport S, Beckerman B. Early development of intractable epilepsy in children: a prospective study. Neurology. 2001. 56:1445–1452.

28. Kim ZS, Lee YS, Lee MS. Two- and four-subtest short forms of the Korean-Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. Seoul J Psychiatry. 1994. 19:121–126.

29. Rhee MK, Lee YH, Jung HY, Choi JH, Kim SH, Kim YK, et al. A standardization study of Beck Depression Inventory (II): Korean version (K-BDI): validity. Korean J Psychopathol. 1995. 4:96–104.

30. Yook SP, Kim ZS. A clinical study on the Korean version of Beck Anxiety Inventory: comparative study of patient and non-patient. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1997. 16:185–197.

31. Kim JH, Kim KI. The standardization study of symptom checklist-90-revision in Korea III. Ment Health Res. 1984. 2:278–311.

32. Shin MS, Park KB, Oh KJ, Kim ZS. A study of suicidal ideation among high school students: the structural relation among depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1990. 9:1–19.

33. Yoo HJ, Lee SA, Heo K, Kang JK, Ko RW, Yi SD, et al. The reliability and validity of Korean QOLIE-31 in patients with epilepsy. J Korean Epilepsy Soc. 2002. 6:45–52.

34. Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. From the Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1981. 22:489–501.

35. Otoul C, Arrigo C, van Rijckevorsel K, French JA. Meta-analysis and indirect comparisons of levetiracetam with other second-generation antiepileptic drugs in partial epilepsy. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2005. 28:72–78.

36. French J, Edrich P, Cramer JA. A systematic review of the safety profile of levetiracetam: a new antiepileptic drug. Epilepsy Res. 2001. 47:77–90.

37. Arroyo S, Crawford P. Safety profile of levetiracetam. Epileptic Disord. 2003. 5:Suppl 1. S57–S63.

39. Wolf P. Acute behavioral symptomatology at disappearance of epileptiform EEG abnormality. Paradoxical or "forced" normalization. Adv Neurol. 1991. 55:127–142.

40. Statistical review and evaluation: antiepileptic drugs and suicidality. 2008. 05. 23. Accessed 2009 Dec 4. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/08/briefing/2008-4372b1-01-FDA.pdf.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download