Abstract

Background and Purpose

Multifocal seeding of the leptomeninges by malignant cells, which is usually referred to as leptomeningeal carcinomatous metastasis, produces substantial morbidity and mortality. The diagnosis of leptomeningeal metastasis is usually established by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) investigation, including cytology, cell counts, protein, glucose, and a tumor marker such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). This study examined the diagnostic value of CEA in the CSF.

Methods

We measured the CSF CEA level in 32 patients with leptomeningeal metastasis. The control group consisted of 19 cancer patients without leptomeningeal metastasis. CEA was measured by the chemiluminescent emission method.

The average human life span is becoming longer due to advances in medical science, and the incidence rate of cancer is increasing. The multifocal spreading of malignant tumor cells along the meninges, which is called leptomeningeal metastasis,1,2 occurs in 5% of all patients diagnosed with cancer. Regardless of the kind of primary cancer, leptomeningeal metastasis results in serious morbidity and mortality.1,3,4

The diagnostic tools for leptomeningeal metastasis include clinical symptoms, neurologic abnormal findings, neurologic imaging, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tests. A CSF cytology test can be used to confirm leptomeningeal metastasis in cancers. The level of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), increased intracranial pressure, cell numbers, and amount of protein are also helpful for the diagnosis.1,5

CEA is a β-1 glycoprotein with a high molecular weight (180 kDa) that is produced in adenocarcinomas such as gastrointestinal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, ovarian cancer, and pancreatic cancer.6-8 Approximately half (50-60%) of this protein is composed of hydrocarbons like sialic acid, mannose, galactose, acetyl-N-glucosamine, and fructose. The other 40% or so is composed of polypeptides. Small amounts of CEA exist in normal digestive organs, and it is present in various bodily fluids such as urine, intestinal secretions, pleural fluid, peritoneal fluid, and CSF.9-11 However, CEA in serum cannot easily pass through the blood-brain barrier, which makes it a good marker for carcinomatous infiltrations in leptomeninges.12-14

Few studies have investigated whether tests for CEA in CSF are useful for diagnosing leptomeningeal metastasis. This study compared CSF CEA levels between cancer patients without leptomeningeal metastasis and cancer patients confirmed as having leptomeningeal metastasis by cytology tests. The aim of this comparison was to determine whether an elevated level of CEA is diagnostic of leptomeningeal metastasis.

Cancer patients with leptomeningeal metastasis were included in this study, with cancer patients without leptomeningeal metastasis being chosen as controls. Patients with parenchymal metastasis to the brain or spinal cord were excluded. None of the patients in the two study groups had medical or neurologic diseases other than cancer.

The patients provided informed consent to participate in the study. For unconscious patients, the informed consent was obtained from their legal guardians. We performed neurological examinations and reviewed medical records. The metastasis group was reviewed for sex, age, previously diagnosed primary cancer site, and metastasis. CSF tests were used to detect malignant cells and to measure the levels of protein, glucose, and CEA.

CSF samples (3 mL) were collected for the tests. When the tests could not be carried out immediately, samples were frozen at -70℃ and then thawed at room temperature when required. The CEA measurement was based on chemiluminescent emissions according to the noncompetitive principle (E170 kit, Modular Analytics, Roche Diagnostic, Mannheim, Germany), and the results were calculated by spectrophotometry at 492 nm.

Obtained values were compared using the t-test with the SPSS statistical analysis program (Version 14.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA), and mean±standard deviation values were determined. The mean age and sex were determined in the metastasis and control groups. CEA, protein and glucose levels were compared using the t-test. Primary cancer was compared between the metastasis and control groups using cross analysis. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Patients in the metastasis group were aged between 34 and 78 years (55.28±10.10 years). Those in the control group were aged between 32 and 88 years (60.94±14.41 years). The age and sex distributions did not differ significantly between the two groups (Table 1).

There were two people aged 30-39 years, seven aged 40-49 years, fifteen aged 50-59 years, four aged 60-69 years, and four aged 70-79 years in the metastatic group. There were two people aged 30-39 years, seven aged 40-49 years, five aged 60-69 years, four aged 70-79 years, and one aged 80-89 years in the control group. In the metastasis group, stomach cancer was most common, followed by lung cancer, breast cancer, esophageal cancer, and cholangiocarcinoma. Stomach cancer was also the most common in the control group, followed by lung cancer, breast cancer, colon cancer, and cholangiocarcinoma (Table 2). Cross analysis revealed that the composition of primary cancer did not differ significantly between the two groups (p=0.218).

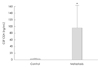

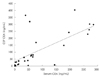

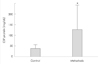

The CEA level was significantly higher in the metastasis group (98.06±59.43 ng/mL) than in the control group (1.53±0.38 ng/mL) (Fig. 1). The ratio of serum and CSF CEA levels was about 1:1 in the metastasis group (Fig. 2).

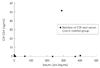

The serum CEA level was higher than 5 ng/mL in 11 patients in the metastasis group, but only 1 (5.2%) patient in the control group had a CSF CEA level of higher than 5 ng/mL (Fig. 3). The ratio of the CSF CEA level (5.16 ng/mL) to the serum CEA level (290.5 ng/mL) wa s nearly 1 : 60.

For a CSF CEA cutoff level of 5 ng/mL, 26 patients in the metastasis group were positive for CSF CEA, whereas only 1 patient was positive in the control group. Therefore, the sensitivity and specificity of CSF CEA were 81.25% and 94.73%, respectively (Table 3).

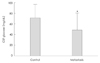

The CSF glucose level was lower in the metastasis group (48.41±32.00 mg/dL) than in the control group (71.53±27.24 mg/dL). Of the 32 patients, 17 (53.1%) had glucose levels equal to or lower than 40 mg/dL (Fig. 4).

The CSF protein level was significantly higher in the metastasis group (129±104 mg/dL) than in the control group (41.66±14.28 mg/dL). Of the 32 patients, 24 (71.8%) had protein levels equal to or higher than 50 mg/dL (Fig. 5).

Many biochemical markers for the early diagnosis of cancer have been investigated. However, the low sensitivity and specificity of serum and CSF levels of biochemical markers have limited their usefulness. Cancer markers are molecules produced and released directly by cancer cells in amounts that exceed those for noncancerous tissues, and so they have a high specificity.12-15 Among these cancer markers, CEA is the most well-known cancer-related antigen that can be found in bodily fluids, and its utility in screening for cancer based on its concentration has been investigated in many studies.7,9

Serum CEA can be used as a secondary tool in screening for groups with a high risk of tumor occurrence, and in situations when the existence of a tumor cannot be readily confirmed. It is also useful during follow-up after cancer treatment, for evaluating treatment effects, and for testing for remnant cancer or cancer recurrence. However, it has a low sensitivity in such applications, and it has also been found to be nonspecifically increased in benign diseases and that many factors contribute to its serum concentration, which reduces its usefulness.16,17

There are two hypotheses for why CEA is detected in CSF,12-15,18,19: 1) CEA in CSF is produced by metastatic tissues and 2) serum CEA passes through the blood-brain barrier. The former hypothesis is more likely since stroke patients with elevated serum CEA do not show elevated CSF CEA levels,20 and the serum CEA level must rise sufficiently to produce a serum-to-CSF ratio of 60 : 1 in order to pass through the blood-brain barrier.12,13,21 Therefore, when the serum-to-CSF ratio is less than 60:1, an increase in CSF CEA level has a relatively high specificity for leptomeningeal metastasis.22 Smoking can also increase the serum CEA level, although not by enough to cause a false-positive result, and this is also true for obesity, age, and sex.23,24 There is little possibility of the CEA level measured in CSF tests being influenced by factors other than tumor metastasis. Therefore, a significant increase in its level can be attributed to the presence of leptomeningeal metastasis.

CSF cytology tests in leptomeningeal metastasis showed a positivity rate of 54% in the first tests, which increased to 85% after three tests.25-28 In some patients with leptomeningeal metastasis, as subsequently confirmed by autopsy, the CSF CEA level was elevated without malignant cells being found in repeated cytology tests.20 This is because cancer cells normally are in one-cell units or form small loose colonies. CSF CEA tests of leptomeningeal metastasis patients in previous studies found a low sensitivity of 31% but a high specificity of 90%.20 However, the sensitivity of CEA in our study was higher than that in previous studies. We attribute this difference to our metastasis group comprising patients who were positive in a cytology test. Even though the CSF CEA test has a low sensitivity, it will be helpful when performing a CSF cytology test.

This study found that the CEA levels were significantly higher in patients diagnosed with leptomeningeal metastasis (as confirmed by finding cancer cells in CSF cytology tests) than in patients without leptomeningeal metastasis. Therefore, CSF CEA tests can be used not only to evaluate the effect of treatment and recurrence of cancer,12,29 but also to diagnose leptomeningeal metastasis. In the metastasis group, 24 patients (71.8%) had a CSF protein level higher than 50 mg/dL and 17 patients (53.1%) had a CSF glucose level lower than 40 mg/dL. These results are similar to those from previous studies.30

We conclude that when findings suspicious of leptomeningeal metastasis such as headaches, vomiting, neurologic disorders, and decreased consciousness are accompanied in patients diagnosed for cancer, testing CEA concentrations in CSF will have an important diagnostic value. In conclusion, elevated serum CEA is influenced by various factors, and so is of limited usefulness in deciding whether tumor metastasis is present. However, an increased CSF CEA appears to be diagnostic of cancer cell metastasis. An increase in protein level or a decrease in glucose level is also useful for the diagnosis of leptomeningeal metastasis.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Comparison of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level between cancer patients with and without leptomeningeal carcinomatous metastasis. The CSF CEA level was significantly higher in patients with leptomeningeal metastasis. Data are mean and SD values. *p=0.002. |

| Fig. 2Relation between CSF and serum CEA levels in the metastasis group. The CSF-to-serum ratio is about 1:1. CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen. |

| Fig. 3Relation between CSF and serum CEA levels in the control group. The CEA level exceeded 5 ng/mL in only 1 of the 19 patients, and the CSF-to-serum CEA ratio was nearly 1 : 60. This suggests that CSF CEA comes from serum CEA passing through the blood-brain barrier. CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen. |

| Fig. 4Comparison of CSF glucose level between patients with and without leptomeningeal metastasis. The CSF glucose level was significantly lower in patients with leptomeningeal metastasis. Data are mean and SD values. *p=0.011. |

| Fig. 5Comparison of CSF protein level between patients with and without leptomeningeal metastasis. The CSF protein was significantly higher in patients with leptomeningeal metastasis. Data are mean and SD values. *p=0.002. |

References

2. Kim SH, Jun DC, Park JS, Heo JH, Kim SM, Kim JH, et al. Primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis: report of a case presenting with chronic meningitis. J Clin Neurol. 2006. 2:202–205.

3. Seidenfeld J, Marton LJ. Biochemical markers of central nervous system tumors measured in cerebrospinal fluid and their potential use in diagnosis and patient management: a review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1979. 63:919–931.

4. Ongerboer de Visser BW, Somers R, Nooyen WH, van Heerde P, Hart AA, McVie JG. Intraventricular methotrexate therapy of leptomeningeal metastasis from breast carcinoma. Neurology. 1983. 33:1565–1572.

5. van Zanten AP, Twijnstra A, Ongerboer de Visser BW, van Heerde P, Hart AA, Nooyen WJ. Cerebrospinal fluid tumour markers in patients treated for meningeal malignancy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991. 54:119–123.

6. Dhar P, Moore T, Zamcheck N, Kupchik HZ. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) in colonic cancer. Use in preoperative and postoperative diagnosis and prognosis. JAMA. 1972. 221:31–35.

8. Reynoso G, Chu TM, Holyoke D, Cohen E, Nemoto T, Wang JJ, et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen in patients with different cancers. JAMA. 1972. 220:361–365.

9. Persijn JP, Korsten CB, Batterman JJ, Tierie AH, Renaud J. Clinical significance of urinary carcino-embryonic antigen estimations during the follow-up of patients with bladder carcinoma or previous bladder carcinoma. Clinical evaluation of carcino-embryonic antigen, III. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1976. 14:395–399.

10. Kalser MH, Barkin JS, Redlhammer D, Heal A. Circulating carcinoembryonic antigen in pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. 1978. 42:3 Suppl. 1468–1471.

11. Loewenstein MS, Rittgers RA, Feinerman AE, Kupchik HZ, Marcel BR, Koff RS, et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen assay of ascites and detection of malignancy. Ann Intern Med. 1978. 88:635–638.

12. Schold SC, Wasserstrom WR, Fleisher M, Schwartz MK, Posner JB. Cerebrospinal fluid biochemical markers of central nervous system metastases. Ann Neurol. 1980. 8:597–604.

13. Wasserstrom WR, Schwartz MK, Fleisher M, Posner JB. Cerebrospinal fluid biochemical markers in central nervous system tumors: a review. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1981. 11:239–251.

14. Snitzer LS, McKinney EC, Tejada F, Sigel MM, Rosomoff HL, Zubrod CG. Letter: Cerebral metastases and carcinoembryonic antigen in CSF. N Engl J Med. 1975. 293:1101.

15. Kido DK, Dyce BJ, Haverback BJ, Rumbaugh CL. Carcinoembryonic antigen in patients with untreated central nervous system tumors. Bull Los Angeles Neurol Soc. 1976. 41:47–54.

16. Norton JA. Carcinoembryonic antigen. New applications for an old marker. Ann Surg. 1991. 213:95–97.

18. Egan ML, Lautenschleger JT, Coligan JE, Todd CW. Radioimmune assay of carcinoembryonic antigen. Immunochemistry. 1972. 9:289–299.

19. Dearnaley DP, Patel S, Powles TJ, Coombes RC. Carcinoembryonic antigen estimation in cerebrospinal fluid in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Oncodev Biol Med. 1981. 2:305–311.

20. Twijnstra A, Nooyen WJ, van Zanten AP, Hart AA, Ongerboer de Visser BW. Cerebrospinal fluid carcinoembryonic antigen in patients with metastatic and nonmetastatic neurological diseases. Arch Neurol. 1986. 43:269–272.

22. Jacobi C, Reiber H, Felgenhauer K. The clinical relevance of locally produced carcinoembryonic antigen in cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurol. 1986. 233:358–361.

23. Herbeth B, Bagrel A. A study of factors influencing plasma CEA levels in an unselected population. Oncodev Biol Med. 1980. 1:191–198.

24. Alexander JC, Silverman NA, Chretien PB. Effect of age and cigarette smoking on carcinoembryonic antigen levels. JAMA. 1976. 235:1975–1979.

25. Kaplan JG, DeSouza TG, Farkash A, Shafran B, Pack D, Rehman F, et al. Leptomeningeal metastases: comparison of clinical features and laboratory data of solid tumors, lymphomas and leukemias. J Neurooncol. 1990. 9:225–229.

26. Little JR, Dale AJ, Okazaki H. Meningeal carcinomatosis. Clinical manifestations. Arch Neurol. 1974. 30:138–143.

28. Ehya H, Hajdu SI, Melamed MR. Cytopathology of nonlymphoreticular neoplasms metastatic to the central nervous system. Acta Cytol. 1981. 25:599–610.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download