Introduction

Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is an infrequently occurring type of cerebrovascular disease with a wide spectrum of clinical presentations and is notoriously difficult to diagnose. Several disorders can cause or predispose patients to CVT, including all medical, surgical, and gyneco-obstetric causes of deep vein thrombosis in the legs, genetic and acquired prothrombotic disorders, cancer, hematological diseases, vasculitis and inflammatory systemic disorders, pregnancy and puerperium, infections, and several local causes such as brain tumors, arteriovenous malformations, head trauma, CNS infections, and ear, sinus, mouth, face, or neck infections.1 Diagnostic and therapeutic procedures such as surgery, lumbar puncture, jugular catheter, and some drugs (particularly oral contraceptives, hormonal replacement therapy, steroids, and cancer treatments) can also cause or predispose people to CVT. However, the relative likelihood of these causes varies with the age and country of origin of the patient.2

In the absence of an obvious provoking risk factor, the presence of an underlying malignancy is often considered because some types of cancer appear to be able to initiate or trigger a thrombotic diathesis through various mechanisms. However, CVT as the presenting sign of occult prostate cancer has not been reported in the English literature. We describe the case of a 69-year-old man with a CVT. The workup for detecting the cause of CVT disclosed occult prostate cancer.

Case Report

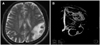

A 69-year-old man was admitted to hospital because of sudden behavioral changes. Three days prior to admission, he experienced difficulty in using a television remote control and writing a letter, he was clumsy with spoons and chopsticks, and he had forgotten the personal identification number of his bank account. He had no history of diabetes, hypertension, smoking, alcoholism, or cardiac disorders. A neurological examination revealed ideational apraxia, finger agnosia, alexia, and right-to-left disorientation. Minimal dysarthria, right central type facial nerve palsy, and pronator drifting of the right arm were also noted. Sensory and cerebellar functions were normal. Brain MRI revealed a hemorrhagic infarction in the left parietal lobe (Fig. 1A). Magnetic resonance (MR) angiography showed no arterial abnormality, but MR venography revealed occlusion of the left transverse sinus (Fig. 1B). The results of the following laboratory tests were normal or negative: electrocardiogram, complete blood cell count, sedimentation rate, blood sugar, lipid battery, homocysteine, fibrinogen degradation products, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, lupus anticoagulant, antithrombin III, factor VIII, antiphospholipid antibody, anticardiolipin antibody, antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, protein C, protein S, C3, C4, CH-50, C-reactive protein, and antistreptolysin O. However, the plasma levels of D-dimer were elevated (1,700 ng/mL).

To search for the predisposing factors of CVT, we performed gastrofiberscopy, colonoscopy, chest CT, abdomen CT, and serological tumor marker studies, but no abnormalities were revealed. The level of prostate specific antigen was markedly elevated (11.8 ng/mL), so an aspiration needle biopsy sample of the prostate gland was taken. Analysis of the sample revealed adenocarcinoma of the prostate.

Discussion

Malignancy is associated with a high risk of developing thromboembolic disease and is related mainly to the generation of an intrinsic hypercoagulable state as a result of tumor induction of platelet aggregation and expression of various procoagulant factors including tissue factor and thrombin. Circulating carcinoma mucins can induce platelet-rich microthrombi without thrombin, a process that is inhibited by heparins but not by warfarin. Activation of the coagulation system appears to be intricately linked to processes that control tumor growth and angiogenesis.3 Expression of tissue factor in tumors leads to an angiogenic phenotype via the up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor and down-regulation of the angiogenesis inhibitor thrombospondin.4

We found no similar reports in the literature of CVT as the presenting sign of occult prostate cancer.5 Most series of thromboembolism associated with occult cancers are about deep venous thrombosis of the legs or pulmonary embolism.3,5 It is not clear what percentage of patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism harbor an asymptomatic occult malignancy. Several studies have found that approximately 8-12% of patients who presented with venous thromboembolism were diagnosed as having cancer after a relatively simple medical examination based upon symptoms and routine laboratory testing.6-8 Over 5% of men diagnosed with prostate cancer have an antecedent thromboembolic event without any traditional risk factors for venous thromboembolism.5 However, there are no case reports involving prostate cancer patients with antecedent CVT in those series.

Because of the wide variety and nonspecificity of the presenting symptoms of CVT, it would be of great practical importance to develop an easy-to-perform test for the emergency room that would reliably rule out CVT. The presence of D-dimer, which comprises fragments of cross-linked fibrin digested by plasmin, indicates the activation of both the blood coagulation system and the fibrinolytic system. Indeed, D-dimer concentrations are increased in most patients with recent CVT so that a negative D-dimer assay result may make the diagnosis of CVT highly unlikely. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of conventional D-dimer levels of >500 ng/mL for the diagnosis of CVT are all 100%.9

Our patient has some features that differ from typical patients with CVT. CVT is a distinct cerebrovascular disorder that, unlike arterial stroke, most often affects young adults and children. The majority (about 75%) of the adult patients are female, but this is not the case for children or the elderly. CVT in elderly people has received little attention. In one study, 8.2% of 624 consecutive adult patients with symptomatic CVT were aged 65 years or older.10 Our case also has several implications for practice. CVT must be included in the differential diagnosis of elderly patients presenting with decreased alertness, delirium, or mental changes, because CVT does not usually present in the elderly as headache or isolated intracranial hypertension.

The coincidence of these two entities cannot be completely ruled out in older patients. However, occult malignancy including prostate cancer should be strongly suspected in older patients with idiopathic CVT.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download