Abstract

Background

Microbleeds (MBs), proposed as a biomarker for microangiopathy, have been suggested as a predictor of spontaneous or thrombolysis-related intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) in acute ischemic stroke. However, the relationship between MBs and warfarin-induced ICH is not clear.

The use of warfarin for preventing ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation has increased dramatically following favorable results from randomized controlled trials in the 1990s.1 This is likely to increase the frequency of warfarin-associated complications,1,2 of which intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is the most serious and lethal, with a mortality of approximately 60%.3 Thus, identifying the risk factors for warfarin-induced ICH might be crucial to improving the risk-to-benefit ratio of warfarin use, and considerable efforts have already been made to identify predictors of warfarin-induced ICH.4,5

An intracerebral microbleed (MB)-a small, dot-like signal loss best visualized on gradient-echo (GRE) imaging-has been regarded as a hemosiderin deposit caused by minor bleeding from advanced microangiopathy.6 Recently there has been growing interest in the role of MBs as a potential risk factor for spontaneous or thrombolysis-related ICH in acute ischemic stroke.7-11 Although MBs have been considered to be pathogenetically related with ICH, their significance as a risk factor for ICH is currently unclear due to inconsistent study results. Moreover, the relationship between MBs and warfarin-induced ICH has never been addressed. Here we report two patients who developed warfarin-induced ICH in the area where MBs had been observed on previous GRE imaging, and discuss the role of MBs in the prediction of warfarin-induced ICH.

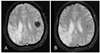

A 58-year-old woman visited the emergency room with sudden dysarthria. She had experienced a stroke 5 years previously, which was a right middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory infarction. Hyperlipidemia was identified as a risk factor for stroke, and thus she had taken statin ever since. She had a left-sided sensory deficit as a sequela, but had no difficulties performing activities of daily living. She had been treated with warfarin because an embolism was presumed to have caused the stroke. There was no history of head trauma or known vascular malformation. On neurological examination, she had moderate dysarthria and a newly developed mild sensory deficit on the right side. Otherwise, no new neurologic abnormality was noted. Her blood pressure was 150/90 mmHg. Laboratory data including CRP were all within normal limits, except for a prothrombin time (PT) of 2.39 international normalized ratio (INR). GRE imaging revealed an acute ICH in the area of the left parietal lobe (Fig. 1A). A review of the MRI images taken 5 years previously revealed an MB at the same location where acute ICH had developed (Fig. 1B). We discontinued warfarin and administered fresh frozen plasma and vitamin K. However, her symptoms gradually worsened, and she had right-sided weakness (MRC grade III) and severe sensory deficit in the right hemibody at the time of discharge.

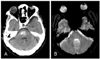

A 78-year-old woman visited the emergency room due to altered mental status. She had a 5-year history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and atrial flutter. She had experienced a left MCA cardioembolic infarction 2 years previously, and had been treated with warfarin, oral hypoglycemic agent, and calcium-channel blocker without any neurologic deficits. She had no previous history of head trauma. On neurological examination, her mental status was semicomatose, and the light reflex in her right eye was sluggish. The corneal reflex and doll's eye movement were absent. She was quadriplegic and showed Babinski's sign on the left. The initial blood pressure was 130/60 mmHg and PT was 2.73 INR. The results of blood cell counts and CRP were unremarkable. Brain CT showed pontine hemorrhage (Fig. 2A). MRI performed 2 years previously showed an MB at the site of acute ICH (Fig. 2B). Her mental status deteriorated rapidly, and her self-respiration vanished. She died 1 month later.

We experienced two patients who had taken warfarin and developed ICH at the location of MBs visualized on previous GRE imaging. Although the patients' INR levels were within the therapeutic range, we believe that they reflected warfarin-induced ICH because we could not find any other causes of ICH such as increased blood pressure, trauma, vascular malformation, or other coagulopathy. Therefore, we suggest that an MB is a preferential focus of ICH in patients receiving warfarin. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the association between MBs and warfarin-induced ICH. These two cases suggest that an MB is a potential risk factor for warfarin-induced ICH, and that information from GRE imaging is valuable when deciding whether to prescribe warfarin for anticoagulation after ischemic stroke.

Several previous studies have addressed the role of MBs in the prediction of ICH or hemorrhagic transformation in ischemic stroke patients. As for thrombolysis-related ICH, the initial study suggested an MB as a potential predictor of ICH after intra-arterial thrombolysis.7 However, the subsequent studies failed to confirm the initial observation due to a lack of statistical power.8,9 It seems unlikely that excluding patients solely based on MB will exceed the benefits gained from thrombolytic therapy. Regarding the short-term and longterm risk of bleeding after antithrombotic therapy, previous studies have found that an MB was a significant independent predictor of hemorrhagic transformation within 1 week10 and subsequent ICH during a 2-year follow-up11 following an acute ischemic stroke. Whether the presence of an MB is indicative of a high risk of secondary ICH after thrombolysis or antithrombotic therapy is currently unclear from the previous studies due to data inconsistencies.

The Stroke Prevention In Reversible Ischemia Trial (SPIRIT) pointed out that old age (>65 years), past history of cerebrovascular disease, and intensity of anticoagulation constituted other clinical and radiological predictors of warfarin-induced ICH.4 Another study showed that the presence of leukoaraiosis was an independent, dose-dependent risk factor for poststroke warfarin-induced ICH.5 Because the mechanisms underlying MBs and leukoaraiosis are thought to be similar (i.e., small-vessel disease), these studies indicate that the marker of chronic, advanced microangiopathy might lead to ICH.

The mechanism by which warfarin induces ICH is not clear. Considering that the lesion distribution does not differ between warfarin-induced ICH and spontaneous ICH, their underlying processes might be similar. The presence of warfarin could result in a tiny bleed enlarging even under normal hemostatic mechanisms.3 Our patients also developed ICHs despite INR levels being within the therapeutic range. The use of warfarin therefore appears to unmask ICH that would otherwise remain asymptomatic.

In conclusion, this case report suggests that the presence of MBs increases the risk of ICH after warfarin administration in ischemic stroke patients. Further large cohort studies are needed to confirm the association of MBs with warfarin-induced ICH.

Figures and Tables

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a grant of the Korea Health 21 R & D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (no. A060171).

References

1. Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Study. Final results. Circulation. 1991. 84:527–539.

2. Flaherty ML, Kissela B, Woo D, Kleindorfer D, Alwell K, Sekar P, et al. The increasing incidence of anticoagulant-associated intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2007. 68:116–121.

3. Hart RG, Boop BS, Anderson DC. Oral anticoagulants and intracranial hemorrhage. Facts and hypotheses. Stroke. 1995. 26:1471–1477.

4. Bleeding during antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. The Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Arch Intern Med. 1996. 156:409–416.

5. Smith EE, Rosand J, Knudsen KA, Hylek EM, Greenberg SM. Leukoaraiosis is associated with warfarin-related hemorrhage following ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2002. 59:193–197.

6. Tanaka A, Ueno Y, Nakayama Y, Takano K, Takebayashi S. Small chronic hemorrhages and ischemic lesions in association with spontaneous intracerebral hematomas. Stroke. 1999. 30:1637–1642.

7. Kidwell CS, Saver JL, Villablanca JP, Duckwiler G, Fredieu A, Gough K, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging detection of microbleeds before thrombolysis: an emerging application. Stroke. 2002. 33:95–98.

8. Derex L, Nighoghossian N, Hermier M, Adeleine P, Philippeau F, Honnorat J, et al. Thrombolysis for ischemic stroke in patients with old microbleeds on pretreatment MRI. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004. 17:238–241.

9. Fiehler J, Albers GW, Boulanger JM, Derex L, Gass A, Hjort N, et al. Bleeding Risk Analysis in Stroke Imaging before thromboLysis (BRASIL): pooled analysis of T2*-weighted magnetic resonance imaging data from 570 patients. Stroke. 2007. 38:2738–2744.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download