Lateral medullary infarction (LMI) is a well-recognized vascular syndrome of the vertebrobasilar territory, which is characterized by the symptoms triad of Horner's syndrome, ipsilateral ataxia, and contralateral hypalgesia.1 Various sensory syndromes in LMI also have been described, with a small variation in the location of a lesion possibly leading to markedly different clinical features due to the complex anatomy of the medulla oblongata.2

Generally, pure sensory stroke has a small number of anatomical localizations and is commonly caused by a lesion in the thalamus.3 Less frequently, pure sensory stroke may be a manifestation of subthalamic, pontine, midbrain, corona radiata, or parietal cortical infarction.3 However, pure sensory stroke is not a feature of LMI. Furthermore, restricted sensory deficits along the somatotopic topography of the spinothalamic tract are less common in LMI. To our knowledge, isolated dermatomal sensory deficit at the T4 sensory level as single manifestation of LMI has not been reported previously. Here we describe a patient with LMI who uniquely presented with a very infrequent dermatomal sensory manifestation without other symptoms of LMI.

CASE REPORT

A 58-year-old man suddenly developed a numb sensation in his trunk and leg on the left side. He had no history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiac problem (including arrhythmia and coronary heart disease), or previous stroke, and he was a nonsmoker. A neurological examination performed the day after presentation revealed that he was alert and oriented, and did not have dysarthria or dysphagia. Both pupils were of equal size and reactive, without nystagmus, ophthalmoplegia, or Horner's syndrome. Other cranial nerves were all normal. Muscle strength was intact in the extremities. A sensory examination including a pinprick test and a cold sensory test revealed that pain and temperature sensations were decreased by about 80% in the left trunk (below the T4 dermatome) and leg. He also complained of paresthesia below the level of the left T4 dermatome. However, he did not report a definite difference in the sensation between the trunk and leg on the left side. Sensory function was intact in the rest of his body, including the face. Vibration and position sensations, two-point discrimination, and graphesthesia were intact. Cerebellar function, as assessed by finger-to-nose, tandem gait, and Romberg's sign test, also was preserved. He complained of an uncomfortable sensation in his left leg and foot on a hopping test, but showed no falling tendency or gait disturbance.

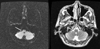

Diffuse- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, performed on the second hospital day, showed a small lesion with a high signal intensity in the right lower medulla oblongata consistent with acute infarction (Fig. 1). Intracranial and neck magnetic resonance angiography showed normal results. Thoracicspine MRI and somatosensory evoked potential (SEP) were performed to exclude spine lesions, and revealed no abnormal findings.

Results from laboratory studies, including complete blood cell and platelet counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, blood electrolytes, chemistry, liver enzymes, cholesterol, triglycerides, and homocysteine, and the prothrombin and partial thromboplastin time were all normal. Chest X-ray, echocardiogram, and electrocardiography also were all normal. The patient was treated with antiplatelet agents, and showed a gradual improvement of sensory deficits to about 60% of normal sensation without fluctuation of symptoms (Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

LMI is one of the most well-characterized vascular infarctions of the brainstem. The clinical features of LMI can have diverse neurological manifestations due to the anatomical characteristics of the medulla.4 According to previous reports, ataxia was the most common neurological symptom in LMI, and was more common in patients with lesions located in the laterocaudal part of the medulla.5 Contralateral hypalgesia is the next most frequent neurological symptom of LMI.4 The most common pattern of sensory abnormality in LMI is loss of pain and heat sensations on the ipsilateral side of the face and on the lower part of the body on the contralateral side, which is associated with other common manifestations such as vertigo, unsteadiness, Horner's syndrome, and dysphagia.3,6 However, pure sensory deficits as an isolated symptom are not a feature of LMI. Moreover, pure sensory deficits in a dermatomal distribution as in the present patient have been not reported previously.

In our case, pure sensory deficit with a T4 sensory level occurred as a single and isolated manifestation of LMI without any of the other common neurological symptoms. We attributed this to the lesion being restricted to the right mediolateral aspect of the medulla, posterior to the inferior olivary nucleus. Moreover, sensory deficit below the T4 level on the contralateral side of the body in our patient was due to the somatotopical organization of the spinothalamic tract, because the sacral afferent fibers are located in the lateral medullary part and the cervical afferent fibers ascend more medially.6 The lesion did not extend sufficiently far to the posterolateral medulla to affect the ipsilateral descending tract and nucleus of the trigeminal nerve, thus sparing sensations in the ipsilateral face. The crossed ventral trigeminothalamic tract courses to the medial part of the spinothalamic tract and carries pain and heat sensations from the contralateral side of the face. Thus, if the lesion extends more medially to involve ipsilateral cervical sensory fibers as well as the contralateral trigeminothalamic tract, this will lead to ipsilateral sensory deficit of the entire body without dermatomal representation or contralateral facial hypesthesia. However, if the lesion extends more posterolaterally to involve the ipsilateral spinocerebellar tract, this will lead to vertigo and ipsilateral ataxia.

Numerous reports have provided evidence that restricted acral sensory deficits frequently occur after small strokes in the thalamic and cortical areas. For example, Fisher stated that isolated paresthesia of the face, arms, and legs suggests thalamic involvement,7 and Kim also observed that dominant sensory involvement of the upper lip, thumbs, and index fingers occurred with thalamic and thalamocortical infarction.8 Therefore, the somatotopic topography of the ventralis posterior nucleus of the thalamus is relatively well known. However, the somatotopic topography is unclear in the brainstem. Lee et al. reported a patient with vibration and position sensory defects below the L5 sensory level caused by medial medullary infarction,9 and Phan and Wijdicks described a patient with pain and temperature sensory losses below the T9 sensory level associated with disequilibrium due to LMI following vertebral artery dissection.10 The present patient represents a rare case of LMI presenting with loss of pain and temperature sensations below the level of the T4 sensory dermatome as a unique neurological deficit. The observations reported here will help to improve our understanding of the somatotopic topography of the brainstem, especially of the medulla.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download