Abstract

Background and Purpose

Chronic daily headache (CDH) is defined as a headache disorder in which headaches occur on a daily or near-daily basis (at least 15 days/month) for more than 3 months. Chronic migraine (CM) and medication overuse headache (MOH) are very disabling headaches that remain underdiagnosed. The aim of this study was to establish the frequency of CDH and its various subtypes, and examine the associations with MOH among first-visit headache patients presenting at neurology outpatient clinics in Korea.

Methods

Eleven neurologists enrolled first-visit patients with complaints of headaches into outpatient clinics for further assessment. Headache disorders were classified according to the International Classification of Headache Disorder (third edition beta version) by each investigator.

Results

Primary CDH was present in 248 (15.2%) of the 1,627 included patients, comprising CM (143, 8.8%), chronic tension-type headache (CTTH) (98, 6%), and definite new daily persistent headache (NDPH) (7, 0.4%). MOH was associated with headache in 81 patients (5%). The association with MOH was stronger among CM patients (34.5%) than patients with CTTH (13.3%) or NDPH (14.3%) (p=0.001). The frequency of CDH did not differ between secondary and tertiary referral hospitals.

Chronic daily headache (CDH) is an umbrella term used to describe headache disorders that are present on more than 15 days per month and persist for longer than 3 months.1 CDH encompasses a broad range of headache disorders that includes primary headache disorders such as chronic migraine (CM), chronic tension-type headache (CTTH), new daily persistent headache (NDPH), and hemicrania continua (HC).1 The prevalence of CDH reportedly ranges from 1% to 5% among the general adult population, and affects 27–39% of headache patients visiting special headache clinics.234 Medication overuse headache (MOH) is defined as the development or marked worsening of a pre-existing headache disorder in association with medication overuse. MOH are usually refractory to treatment, and patients with CDH experience a remarkable degree of disability.5678

Recent advances in medicine may provide an opportunity for the successful treatment of CM and MOH, but most CM and MOH patients do not receive the correct diagnosis at their initial visit.910 The failure of patients to accurately report headaches often results in the misdiagnosis of CDH as episodic headaches, which may lead to incorrect and delayed treatment of CDH.11 Therefore, diagnosing headache disorders based on a detailed patient history and standardized diagnostic criteria is crucial. New diagnostic criteria for CM and MOH were recently published in the third edition beta version of the International Classification of Headache Disorder (ICHD-3β).12 Most previous studies of MOH or CDH have applied the previous version or ICHD-3β retrospectively,101213 and so the frequency of CDH and MOH still needs to be evaluated in a clinic-based setting according to ICHD-3β. The early detection and accurate diagnosis of CM and MOH in CDH patients in neurology clinics is important because only 20–36% of them are reportedly correctly diagnosed by a physician or specialist.914

The aim of this multicenter study was to estimate the frequency of CDH, its subtypes, and MOH using ICHD-3β in Korea.

This investigation was based on the Headache Registry using ICHD-3β for First-Visit Patients (HEREIN) study, which is a cross-sectional multicenter registry study that uses data collected from first-visit headache outpatients presenting at neurology clinics in Korea between August 2014 and February 2015.151617

Briefly, the inclusion criteria for the patients were as follows: 1) aged 19–100 years and have a primary complaint of headaches at the outpatient visit, 2) having no communication disability that might interfere with the collection of medical history, and 3) being willing to participate in the study. We excluded patients who: 1) had a chief complaint other than headaches, 2) had any significant communication problems in hearing, speaking, or cognition, or 3) had any other serious medical or psychiatric problems that might impede continuation of the study according to the physician's judgment.

This study was conducted in six tertiary referral university hospitals, three secondary referral university hospitals, and two secondary referral general hospitals in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice. The study protocol and the informed consent and information use agreement forms were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of each center (Dongtan Sacred Heart Hospital Institutional Review Board/Ethic Committee IRB approval number: 2014-018). Each patient provided written informed consent prior to their participation in the study or waived the informed consent process according to the decision of the institutional review board of each center.

The classification of a headache disorder was established by each investigator using the current headache phenotypes described in ICHD-3β. This was determined according to the initial evaluation of the patients using a structured questionnaire, a clinical evaluation, and laboratory or neuroimaging studies, as necessary. The history of headache were obtained at the initial visit, which included the routes of access to the hospitals, onset times of the first and the current headaches, presence of aura, severity as assessed on a visual analog scale (VAS), and duration of headache attacks. The investigators selected the most appropriate headache subtype for each patient, and MOHs were assessed separately. Before enrolling patients, all investigators were informed about ICHD-3β principles during an educational meeting and a further session was convened to confirm any uncertain cases. CM, CTTH, NDPH, and HC were defined by ICHD-3β as CDH when patients experienced headaches at least 15 days per month for at least 3 months and for longer than 4 hours per day.118 Any probable diagnoses were excluded from enrollment of CDH. Migraine with aura, migraine without aura, and probable migraine with headache on fewer than 15 days per month were classified as episodic migraine (EM). Infrequent episodic tension-type headache (ETTH), frequent ETTH, and probable ETTH were together classified as ETTH.19 MOH was diagnosed according to ICHD-3β criteria.

All analyses were performed using SPSS (Windows version 21.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), and a p value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Demographic characteristics were compared using an independent-samples t-test or a chi-square test for categorical variables. Methods of analysis such as the t-test, chi-square test, and ANOVA were used for comparisons between patients with CM, CTTH, EM, and ETTH. ANOVA was used to assess MOH in CDH patients. The data are presented as mean±SD values.

Of 1,627 patients, CDH was diagnosed in 248 patients (15.2%) and MOH was diagnosed in 81 patients (5%), which included CM (n=143, 8.8%), CTTH (n=98, 6.0%), and NDPH (n=7, 0.4%). No patient fulfilled the criteria for HC. The age at the diagnosis of CDH was 50.1±15.2 years, and the age at onset of CDH was 41.88±16.82 years. Most of those diagnosed with CDH were aged 50–59 years, whilst headache onset occurred mainly in those aged 40–49 years (Fig. 1).

An additional diagnosis of MOH was made in 49 CM, 13 CTTH, 1 NDPH, 9 episodic headache (7 migraine without aura, 1 frequent ETTH, and 1 probable tension-type headache), and 9 secondary headache patients. Three MOH patients received an additional diagnosis of a secondary headache disorder, including headache attributed to traumatic head injury (ICHD-3β code 5.2, n=1), alcohol-induced headache (ICHD-3β code 8.1.4, n=1), and cervicogenic headache (ICHD-3β code 11.2.1, n=1). The remaining six patients were diagnosed with MOH without an additional diagnosis because there were no symptoms that were better accounted for by another ICHD-3β diagnosis. The frequency of MOH was 25.4% among CDH patients. An additional diagnosis of MOH was more common in CM patients (34.5%) than in CTTH patients (13.3%) or NDPH patients (14.3%) (p=0.001) (Fig. 2).

The overused medications involved in MOH were mainly combination analgesics (n=34, 42%) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (n=23, 28.4%), followed by other drugs (n=15, 18.5%), triptans (n=5, 6.2%), ergot derivatives (n=2, 2.5%), and opioid analgesics (n=2, 2.5%).

The frequency of CDH did not differ according to the hospital setting [secondary vs. tertiary referral hospitals, n=123 (15%) vs. n=125 (15.5%), p=0.816]. The frequency of MOH also did not differ according to the hospital setting (secondary vs. tertiary referral hospitals, 4.4% vs. 5.6%, p=0.282).

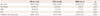

The CM patients were significantly younger than the CTTH patients (45.6±14.6 years vs. 56.6±13.8 years, p<0.001). CM was more common in women (p<0.001), with a higher incidence of MOH than CTTH (34.3% vs. 13.3%, p<0.001). The VAS score was higher in CM than in CTTH (7.3±1.5 vs. 5.2±1.9, p<0.001). The headache onset occurred significantly earlier in CM patients than in CTTH patients (34.9±14.7 years vs. 51.5±14.7 years, p<0.001) (Table 1).

CDH was more common in women (p<0.001) and occurred in older patients relative to episodic primary headache (EPH) (50.12±15.21 years vs. 46.55±14.26 years, p<0.001). Headache duration was longer in CDH than in EPH (64.22±11.01 years vs. 35.56±77.83 years, p<0.001), and the frequency of MOH was higher in CDH than in EPH (25.4% vs. 12.5%, p<0.001). VAS score and age at headache onset did not differ significantly between CDH and EPH (Table 2).

The proportion of women was higher in CDH patients with MOH than in those without MOH (p=0.006). The severity and duration of headache were significantly greater and longer, respectively, in CDH with MOH than in CDH alone (p=0.003 vs. p<0.001) (Table 3).

Compared to EM, CM was more common in women (p=0.004) and had a higher incidence of MOH (34.3% vs. 1.3%, p<0.001). The VAS score (7.3±1.5 vs. 7.0±1.9, p=0.156) and headache onset age (32.7±12.9 years vs. 34.9±14.7 years, p=0.116) did not differ significantly between CM and EM.

Compared to ETTH, CTTH was detected more commonly in women (p=0.018) and was more frequently accompanied by MOH (13.3% vs. 0.6%, p<0.001). The age at headache onset did not differ between CTTH and ETTH (51.5±14.7 years vs. 49.6±14.2 years, p=0.244). The VAS score tended to be higher in CTTH than ETTH (5.2±1.9 vs. 4.6±1.6, p=0.050), but with marginal significance (Table 4).

Our study is the first to investigate the frequencies of CDH and MOH, as diagnosed using ICHD-3β in first-visit headache patients presenting at neurology clinics in Korea. The frequency of CDH was 15.2%, of which two-thirds were patients with CM (57.7%) and the frequency of MOH was 5%. About 60% of MOH patients had a primary diagnosis of CM, and one-third of CM patients received an additional diagnosis of MOH.

According to ICHD-3β, patients meeting criteria for CM and MOH should be given both diagnoses.12 About two-thirds of CM patients met MOH criteria in the PREEMPT (Phase III Research Evaluating Migraine Prophylaxis Therapy) study, and medication overuse is a criterion of the IDCM tool used to screen CM.1120 A previous study found that 44.6% of MOH patients retrospectively received a diagnosis of CM using ICHD-3β, and this association can vary according to the applied diagnostic criteria.10 The association between CM and MOH is clinically very important, and the present study supports the usefulness of ICHD-3β in the diagnosis and management of CDH.21

The frequency of CDH in this study was higher than the frequency of approximately 10% reported when using Second edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorder in neurology clinics.4 This difference may be related to the change in diagnostic criteria for CM that allowed the inclusion of MOH and migraine with aura.16 This conclusion might be supported by the higher proportion of CM patients in the CDH category. The frequency of CDH found in the present study might differ considerably from that for the general population. Population-based studies have found the frequency of CDH to be 2.0–7.6% in Western countries2222324 and 1.0–3.9% in Asian countries, including Korea.252627 Comparatively, the frequency of CDH was approximately 40% in specialized headache clinics in the USA2829 and 23–79% in Asia.30313233

The frequency of MOH in neurology clinics was 5% in this study. According to ICHD-3β, MOH can be diagnosed in patients presenting with headache on more than 15 days per month and with a history of regular medication overuse for more than 3 months. Therefore, some patients with MOH did not meet the "3 months" criterion of CDH, and those MOH patients with primary headache disorders were not diagnosed with CDH in this study. The prevalence of MOH was previously found to be 1–5% in the general population and 10–15.9% in patients presenting at headache clinics.3435363738 The proportion of patients with triptan overuse in the present study was 6%, and the proportions of patients with overuse of other medications were similar to those found in previous studies.1339

One-quarter (25.4%) of CDH patients received an additional diagnosis of MOH. The estimated prevalence of MOH among CDH has ranged from 11% to 41% in several population-based studies, and was 15–31% in outpatient-clinic-based studies.26274041424344 These variations in the prevalence of MOH might be related to the application of different diagnostic criteria and the inclusion of different study populations. In our study, the headache severity was greater in CDH patients with MOH than in those without MOH.

Approximately two-thirds of our CDH and MOH patients were diagnosed with CM (57.7% and 60.5%, respectively). The presenting symptoms were more severe in CM patients than in CTTH patients. A secondary diagnosis of MOH was more likely in CM patients than in EM patients. Patients with CM reported having a greater degree of disability than those with EM.4546 The finding that CM is the predominant CDH phenotype is encouraging because CM treatments have progressed markedly in recent years.474849

More than one-third of patients (39.5%) with CDH were CTTH sufferers, and the likelihood of an MOH diagnosis was higher in CTTH patients than in ETTH patients. With regard to the onset of headache and VAS score, there were no significant differences between CTTH and ETTH, in contrast to the case for migraine.

This study was subject to several limitations. Headache-related disability, the impact of headache, and the various comorbidities of CDH and MOH were not evaluated.4650 Secondly, CDH and MOH were diagnosed by each investigator based on ICHD-3β criteria. We did not collect information regarding the number of headache days each month, and so secondary headache patients presenting with daily or near-daily headache over a 3-month period were not evaluated.5152 The severity or impact of headache could be associated with the number of headache days or days on medication, and hence these variables and the frequency of secondary CDH should be evaluated in future studies.

In summary, the frequency of CDH among first-visit headache patients was 15.2%, with MOH occurring in 5% of the patients when using ICHD-3β in a multicenter study in Korea. The most common subtype of CDH and MOH was CM, which indicates that advanced strategies for CM treatment would be beneficial in improving CDH and MOH.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 2Proportion of medication overuse headache (MOH) among patients with CDH and other headache disorders. CDH: chronic daily headache, NDPH: new daily persistent headache, TTH: tension-type headache. |

Table 1

Comparison between demographic characteristics in chronic migraine (CM), chronic tension-type headache (CTTH), and new daily persistent headache (NDPH)

Table 2

Comparison between demographic characteristics in chronic daily headache (CDH) and episodic primary headache (EPH)

Table 3

Comparison between demographic characteristics in CDH alone and CDH with MOH

Table 4

Comparisons between demographic characteristics in CM and episodic migraine (EM), and in chronic tension-type headache (CTTH) and episodic tension-type headache (ETTH)

References

1. Siberstein SD, Lipton RB, Solomon S, Mathew NT. Classification of daily and near-daily headaches: proposed revisions to the IHS criteria. Headache. 1994; 34:1–7.

2. Scher AI, Stewart WF, Liberman J, Lipton RB. Prevalence of frequent headache in a population sample. Headache. 1998; 38:497–506.

3. Castillo J, Muñoz P, Guitera V, Pascual J. Kaplan Award 1998. Epidemiology of chronic daily headache in the general population. Headache. 1999; 39:190–196.

4. Pascual J, Colás R, Castillo J. Epidemiology of chronic daily headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2001; 5:529–536.

5. Burch RC, Loder S, Loder E, Smitherman TA. The prevalence and burden of migraine and severe headache in the United States: updated statistics from government health surveillance studies. Headache. 2015; 55:21–34.

6. Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Morganstein D, Lipton R. Lost productive time and cost due to common pain conditions in the US workforce. JAMA. 2003; 290:2443–2454.

7. Meletiche DM, Lofland JH, Young WB. Quality-of-life differences between patients with episodic and transformed migraine. Headache. 2001; 41:573–578.

8. Bendtsen L, Munksgaard S, Tassorelli C, Nappi G, Katsarava Z, Lainez M, et al. Disability, anxiety and depression associated with medication-overuse headache can be considerably reduced by detoxification and prophylactic treatment. Results from a multicentre, multinational study (COMOESTAS project). Cephalalgia. 2014; 34:426–433.

9. Bigal ME, Serrano D, Reed M, Lipton RB. Chronic migraine in the population: burden, diagnosis, and satisfaction with treatment. Neurology. 2008; 71:559–566.

10. Tassorelli C, Jensen R, Allena M, De Icco R, Sances G, Katsarava Z, et al. A consensus protocol for the management of medication-overuse headache: evaluation in a multicentric, multinational study. Cephalalgia. 2014; 34:645–655.

11. Lipton RB, Serrano D, Buse DC, Pavlovic JM, Blumenfeld AM, Dodick DW, et al. Improving the detection of chronic migraine: development and validation of Identify Chronic Migraine (ID-CM). Cephalalgia. 2016; 36:203–215.

12. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013; 33:629–808.

13. Shand B, Goicochea MT, Valenzuela R, Fadic R, Jensen R, Tassorelli C, et al. Clinical and demographical characteristics of patients with medication overuse headache in Argentina and Chile: analysis of the Latin American section of COMOESTAS Project. J Headache Pain. 2015; 16:83.

14. Adams AM, Serrano D, Buse DC, Reed ML, Marske V, Fanning KM, et al. The impact of chronic migraine: The Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study methods and baseline results. Cephalalgia. 2015; 35:563–578.

15. Cho SJ, Kim BK, Kim BS, Kim JM, Kim SK, Moon HS, et al. Vestibular migraine in multicenter neurology clinics according to the appendix criteria in the third beta edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders. Cephalalgia. 2016; 36:454–462.

16. Kim BK, Cho SJ, Kim BS, Sohn JH, Kim SK, Cha MJ, et al. Comprehensive application of the International Classification of Headache Disorders third edition, beta version. J Korean Med Sci. 2016; 31:106–113.

17. Kim SK, Moon HS, Cha MJ, Kim BS, Kim BK, Park JW, et al. Prevalence and features of a probable diagnosis in first-visit headache patients based on the criteria of the Third Beta Edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders: a prospective, crosssectional multicenter study. Headache. 2016; 56:267–275.

18. Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Sliwinski M. Classification of daily and near-daily headaches: field trial of revised IHS criteria. Neurology. 1996; 47:871–875.

19. Lipton RB, Silberstein SD. Episodic and chronic migraine headache: breaking down barriers to optimal treatment and prevention. Headache. 2015; 55:Suppl 2. 103–122. quiz 123-126.

20. Silberstein SD, Blumenfeld AM, Cady RK, Turner IM, Lipton RB, Diener HC, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: PREEMPT 24-week pooled subgroup analysis of patients who had acute headache medication overuse at baseline. J Neurol Sci. 2013; 331:48–56.

21. Sun-Edelstein C, Bigal ME, Rapoport AM. Chronic migraine and medication overuse headache: clarifying the current International Headache Society classification criteria. Cephalalgia. 2009; 29:445–452.

22. Queiroz LP, Peres MF, Kowacs F, Piovesan EJ, Ciciarelli MC, Souza JA, et al. Chronic daily headache in Brazil: a nationwide populationbased study. Cephalalgia. 2008; 28:1264–1269.

23. Stovner Lj, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton R, Scher A, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007; 27:193–210.

24. Lantéri-Minet M, Auray JP, El Hasnaoui A, Dartigues JF, Duru G, Henry P, et al. Prevalence and description of chronic daily headache in the general population in France. Pain. 2003; 102:143–149.

25. Yu S, Liu R, Zhao G, Yang X, Qiao X, Feng J, et al. The prevalence and burden of primary headaches in China: a population-based door-to-door survey. Headache. 2012; 52:582–591.

26. Lu SR, Fuh JL, Chen WT, Juang KD, Wang SJ. Chronic daily headache in Taipei, Taiwan: prevalence, follow-up and outcome predictors. Cephalalgia. 2001; 21:980–986.

27. Park JW, Moon HS, Kim JM, Lee KS, Chu MK. Chronic daily headache in Korea: prevalence, clinical characteristics, medical consultation and management. J Clin Neurol. 2014; 10:236–243.

29. Mathew NT, Stubits E, Nigam MP. Transformation of episodic migraine into daily headache: analysis of factors. Headache. 1982; 22:66–68.

30. Wang Y, Zhou J, Fan X, Li X, Ran L, Tan G, et al. Classification and clinical features of headache patients: an outpatient clinic study from China. J Headache Pain. 2011; 12:561–567.

31. Juang KD, Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Lu SR, Su TP. Comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders in chronic daily headache and its subtypes. Headache. 2000; 40:818–823.

32. Takase Y. [Chronic daily headache and medication-induced headache]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2004; 44:815–817.

33. Srikiatkhachorn A, Phanthumchinda K. Prevalence and clinical features of chronic daily headache in a headache clinic. Headache. 1997; 37:277–280.

34. Colás R, Muñoz P, Temprano R, Gómez C, Pascual J. Chronic daily headache with analgesic overuse: epidemiology and impact on quality of life. Neurology. 2004; 62:1338–1342.

35. Dowson AJ. Analysis of the patients attending a specialist UK headache clinic over a 3-year period. Headache. 2003; 43:14–18.

36. Zebenholzer K, Andree C, Lechner A, Broessner G, Lampl C, Luthringshausen G, et al. Prevalence, management and burden of episodic and chronic headaches--a cross-sectional multicentre study in eight Austrian headache centres. J Headache Pain. 2015; 16:531.

37. Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Katsarava Z, Lainez JM, Lampl C, Lantéri-Minet M, et al. The impact of headache in Europe: principal results of the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain. 2014; 15:31.

39. Chagas OF, Éckeli FD, Bigal ME, Silva MO, Speciali JG. Study of the use of analgesics by patients with headache at a specialized outpatient clinic (ACEF). Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2015; 73:586–592.

40. Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Lu SR, Liu CY, Hsu LC, Wang PN, et al. Chronic daily headache in Chinese elderly: prevalence, risk factors, and biannual follow-up. Neurology. 2000; 54:314–319.

41. Stark RJ, Ravishankar K, Siow HC, Lee KS, Pepperle R, Wang SJ. Chronic migraine and chronic daily headache in the Asia-Pacific region: a systematic review. Cephalalgia. 2013; 33:266–283.

42. Karbowniczek A, Domitrz I. Frequency and clinical characteristics of chronic daily headache in an outpatient clinic setting. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2011; 45:11–17.

43. Huang Q, Li W, Li N, Wang J, Tan G, Chen L, et al. Elevated blood pressure and analgesic overuse in chronic daily headache: an outpatient clinic-based study from China. J Headache Pain. 2013; 14:51.

44. Katsarava Z, Dzagnidze A, Kukava M, Mirvelashvili E, Djibuti M, Janelidze M, et al. Primary headache disorders in the Republic of Georgia: prevalence and risk factors. Neurology. 2009; 73:1796–1803.

45. Kim SY, Park SP. The role of headache chronicity among predictors contributing to quality of life in patients with migraine: a hospitalbased study. J Headache Pain. 2014; 15:68.

46. Wang SJ, Wang PJ, Fuh JL, Peng KP, Ng K. Comparisons of disability, quality of life, and resource use between chronic and episodic migraineurs: a clinic-based study in Taiwan. Cephalalgia. 2013; 33:171–181.

47. Yurekli VA, Akhan G, Kutluhan S, Uzar E, Koyuncuoglu HR, Gultekin F. The effect of sodium valproate on chronic daily headache and its subgroups. J Headache Pain. 2008; 9:37–41.

48. Diener HC, Dodick DW, Aurora SK, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, Lipton RB, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 2 trial. Cephalalgia. 2010; 30:804–814.

49. D'Amico D. Pharmacological prophylaxis of chronic migraine: a review of double-blind placebo-controlled trials. Neurol Sci. 2010; 31:Suppl 1. S23–S28.

50. Cho SJ, Chu MK. Risk factors of chronic daily headache or chronic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2015; 19:465.

51. Dodick DW. Clinical practice. Chronic daily headache. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354:158–165.

52. Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Dalessio DJ. Wolff's headache and other head pain. 7th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press;2001.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download