Abstract

Background

Dabigatran etexilate, a new oral anticoagulant, was recently approved as an efficacious alternative to warfarin for the prevention of first and recurrent stroke in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Limited data are available for dabigatran use in patients with a creatinine clearance rate (CrCL) of 15-30 mL/min. Furthermore, current guidelines do not recommend frequent blood monitoring after dabigatran use. We report herein a patient with severe renal dysfunction who exhibited profound coagulopathy after 2 days of dabigatran use.

Case Report

An 87-year-old woman was admitted for altered mental status and left-side weakness. She was diagnosed with right middle cerebral artery infarction. The baseline assessment revealed a serum creatinine concentration of 1.29 mg/dL and a CrCL of 27.2 mL/min. Dabigatran therapy was started 5 weeks after admission at a dosage of 110 mg twice daily. After 2 days of dabigatran use, the patient developed multiple bruises and evidence of upper-gastrointestinal bleeding. Laboratory tests demonstrated a severe coagulopathy, with a prothrombin time of 85.9 sec, an international normalized ratio of 11.36, an activated partial thromboplastin time of 119.2 sec, and a thrombin time of 230.8 sec. Serial assessment of the patient's renal function revealed substantial fluctuation of the CrCL (range, 17.9-26.5 mL/min).

Dabigatran etexilate, an oral direct thrombin inhibitor, was recently approved for primary and secondary stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). The results of the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) trial led to the conclusion that taking dabigatran at 150 mg twice daily is superior to warfarin therapy and has an equivalent bleeding risk.1 The American Heart/Stroke Association recommends taking dabigatran at 150 mg twice daily as an efficacious alternative to warfarin for the prevention of first and recurrent stroke in patients with nonvalvular AF who have normal renal function.2 The European Society for Cardiology and Canadian Cardiovascular Society recommend a dose of 110 mg twice daily on an individual basis and at the physician's discretion in patients with low thromboembolic and high bleeding risks.3,4 Since the 150-mg dose of dabigatran may be more likely to cause major bleeding among those older than 75 years,5 it seems prudent to prescribe dabigatran at 110 mg in these patients.4

Dabigatran is excreted predominantly by the kidneys, and so the use of dabigatran is not recommended if the creatinine clearance rate (CrCL) is <15 mL/min or if the patient is receiving dialysis.2 The United States Food and Drug Administration approved dabigatran at 75 mg twice daily for patients with a CrCL of 15-30 mL/min. The European guideline is stricter and does not recommended new oral anticoagulants (NOAC) in patients with severe renal impairment (CrCL, <30 mL/min).3 Limited data are available for other NOAC in patients with severe renal impairment.

The use of dabigatran has been increasing due to the many limitations of warfarin, including a labile prothrombin time (PT) and the need for frequent blood sampling. Given that routine blood monitoring is not necessary in most patients taking dabigatran,6,7 both physicians and patients are often either unwilling or forget to perform blood tests regularly after the use of NOAC. However, in addition to the baseline assessment of renal function, short-term follow-up assessment of the patient's renal function and coagulopathy profile may be important, especially in those with moderate-to-severe renal impairment.

We report herein a patient with severe renal dysfunction who developed profound coagulopathy after 2 days of dabigatran use.

An 87-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency room for altered mental status and left-side weakness. She had been treated with warfarin and aspirin for 2 years due to AF, ischemic stroke, and myocardial infarction. She had also been diagnosed and managed for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and ischemic cardiomyopathy. A neurologic examination revealed a stuporous mental status, unresponsiveness to visual threatening, gaze preponderance to the right side, and left-sided hemiparesis. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed acute ischemic infarction in the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory and chronic infarction in the left MCA territory. The transthoracic echocardiogram findings were consistent with ischemic heart disease with moderate left-ventricular systolic dysfunction (left-ventricular ejection fraction, 30-35%), AF with enlargement of both atria, and moderate tricuspid regurgitation with borderline pulmonary hypertension. Coagulation assays were performed with a Stago STA-R device. The activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) was 30.8 sec (reference, 29.1-41.9 sec) and the international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.24 (reference, 0.90-1.10).

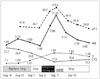

The decision was made to change from warfarin to dabigatran because the patient suffered a recurrent stroke despite receiving warfarin treatment. In addition, frequent measurement of INR could not be performed after discharge due to severe neurologic deficits. A baseline assessment revealed that she had a serum creatinine concentration of 1.29 mg/dL, an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 38.7 mL/min/1.73 m2, and a CrCL of 27.2 mL/min. Dabigatran was started at a dosage of 110 mg twice daily, 2 days after cessation of warfarin. The patient developed multiple bruises after 2 days of dabigatran use, and small old blood clot was observed in her nasogastric tube. Blood sampling revealed severe coagulopathy (Fig. 1), with a PT of 65.4 sec (reference, 12.6-14.9 sec), an INR of 7.99, and an aPTT of 99.7 sec. A repeat assessment performed 4 hours later revealed that the PT and aPTT were further prolonged (to 85.9 and 119.2 sec, respectively), the INR had increased (11.36), and she had a prolonged thrombin time of 230.8 sec (reference, 14.2-16.5 sec). The patient received a vitamin K injection and dabigatran was discontinued; 7 days later the PT was normalized, with an INR of 1.09 and an aPTT of 34.8 sec, but the thrombin time was still prolonged at 61.5 sec. Serial assessment of renal function revealed substantial fluctuation in the CrCL (range, 17.9-26.5 mL/min) (Fig. 1).

The present case was a patient who developed profound coagulopathy after 2 days of low-dose dabigatran use. Although the RE-LY trial excluded patients with severe renal dysfunction, a lower dose (75 mg twice a day) was approved for patients with a CrCL of 15-30 mL/min, based on pharmacokinetic-but not clinical-safety data.6 This case raises the possibility of bleeding risk in patients with moderate-to-severe renal dysfunction, even after the use of low-dose dabigatran.

Baseline and subsequent regular assessments of renal function (usually annually, but two or three times per year in those with moderate renal impairment) are currently recommended in patients following initiation of NOAC.3,8 Interestingly, the present case shows that due to the possible fluctuation of renal function in some patients, an annual measurement of renal function may not be sufficient to secure the safety of dabigatran use.

This case also highlights the need for assessment of the coagulation profile soon after the commencement of NOAC in patients with renal dysfunction. The guidelines do not recommend routine blood monitoring with dabigatran;6 however, the present case emphasizes the need for assessment of the coagulation profile before and soon after starting NOAC. Furthermore, the INR prolongation in this patient was remarkable. Although dabigatran reportedly has relatively less effect on PT than thrombin time, ecarin clotting time assay findings, and aPTT,9 Legrand et al.10 reported two cases of INR prolongation in elderly subjects with dabigatran use: as in the present case, both were elderly females (84 and 89 years old) and both had moderate-to-severe renal dysfunction (CrCL, 32 and 29 mL/min, respectively).

In conclusion, the case described herein emphasizes the need for frequent assessment of renal function and coagulation assays including PT, after commencing NOAC in patients with moderate-to-severe renal impairment.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Laboratory findings before and after starting dabigatran therapy (at 110 mg twice daily). Dashed line=aPTT (sec); solid black line=PT (INR); solid gray line=CrCL (mL/min); dotted line= creatinine (mg/dL). aPTT: activated partial thromboplastin time, Cr: creatinine, CrCL: creatinine clearance rate, INR: international normalized ratio, PT: prothrombin time, Vit K: vitamin K |

References

1. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:1139–1151.

2. Furie KL, Goldstein LB, Albers GW, Khatri P, Neyens R, Turakhia MP, et al. Oral antithrombotic agents for the prevention of stroke in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a science advisory for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2012; 43:3442–3453.

3. Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, Savelieva I, Atar D, Hohnloser SH, et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2012; 33:2719–2747.

4. Skanes AC, Healey JS, Cairns JA, Dorian P, Gillis AM, McMurtry MS, et al. Focused 2012 update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society atrial fibrillation guidelines: recommendations for stroke prevention and rate/rhythm control. Can J Cardiol. 2012; 28:125–136.

5. Eikelboom JW, Wallentin L, Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz M, Healey JS, Oldgren J, et al. Risk of bleeding with 2 doses of dabigatran compared with warfarin in older and younger patients with atrial fibrillation: an analysis of the randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy (RE-LY) trial. Circulation. 2011; 123:2363–2372.

6. Alberts MJ, Bernstein RA, Naccarelli GV, Garcia DA. Using dabigatran in patients with stroke: a practical guide for clinicians. Stroke. 2012; 43:271–279.

7. Hankey GJ, Eikelboom JW. Dabigatran etexilate: a new oral thrombin inhibitor. Circulation. 2011; 123:1436–1450.

8. Alberts MJ, Eikelboom JW, Hankey GJ. Antithrombotic therapy for stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Lancet Neurol. 2012; 11:1066–1081.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download