This article has been corrected. See "Erratum: Depression and Anxiety in People with Epilepsy" in Volume 10 on page 375.

Abstract

Many recent epidemiological studies have found the prevalence of depression and anxiety to be higher in people with epilepsy (PWE) than in people without epilepsy. Furthermore, people with depression or anxiety have been more likely to suffer from epilepsy than those without depression or anxiety. Almost one-third of PWE suffer from depression and anxiety, which is similar to the prevalence of drug-refractory epilepsy. Various brain areas, including the frontal, temporal, and limbic regions, are associated with the biological pathogenesis of depression in PWE. It has been suggested that structural abnormalities, monoamine pathways, cerebral glucose metabolism, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and interleukin-1b are associated with the pathogenesis of depression in PWE. The amygdala and the hippocampus are important anatomical structures related to anxiety, and γ-aminobutyric acid and serotonin are associated with its pathogenesis. Depression and anxiety may lead to suicidal ideation or attempts and feelings of stigmatization. These experiences are also likely to increase the adverse effects associated with antiepileptic drugs and have been related to poor responses to pharmacological and surgical treatments. Ultimately, the quality of life is likely to be worse in PWE with depression and anxiety than in PWE without these disorders, which makes the early detection and appropriate management of depression and anxiety in PWE indispensable. Simple screening instruments may be helpful for in this regard, particularly in busy epilepsy clinics. Although both medical and psychobehavioral therapies may ameliorate these conditions, randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm that.

More than 2000 years ago, Hippocrates described a bidirectional relationship between depression and epilepsy.1 He wrote, "Melancholics ordinarily become epileptics, and epileptics, melancholics: what determines the preference is the direction the malady takes."1 Many physicians have since noticed a connection between epilepsy and depression and anxiety. However, comorbid depression and anxiety disorders in people with epilepsy (PWE) have not been a focus in the field of epilepsy research and management for a long time, although many recent epidemiological studies have found a high prevalence of depression and anxiety in PWE.2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 These studies found that 9-37% of PWE suffered from depression and 11-25% suffered from anxiety, which are higher proportions than found in those without epilepsy. These rates of depression and anxiety were close to that of drug-refractory epilepsy in a long-term population-based study.12 Despite major advances in the understanding and management of drug-refractory epilepsy, issues related to depression and anxiety in PWE remain underrecognized.

The prevalence of depression or anxiety is higher in drug-refractory epilepsy, and especially temporal-lobe epilepsy (TLE), than in the general population of PWE.2,4,7,13,14,15,16,17 Depression and anxiety are associated with suicide, suicidal ideation, and stigmatization in PWE.2,18,19,20,21 Recent studies have identified depression and anxiety as risk factors of drug-refractory epilepsy in newly diagnosed epileptic patients.22,23 These risk factors have also been associated with worse outcomes of epileptic surgery.24,25 In addition, depression and anxiety have been associated with increased adverse events in response to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) in PWE.26,27,28,29 Ultimately, the psychiatric and clinical effects of depression and anxiety can impair the quality of life (QOL) of PWE. Therefore, early detection and management of depression and anxiety are critical for the management of PWE. Many valuable reports about depression and anxiety in PWE have been published. This review was designed to compile the information provided by these studies, organizing it according to epidemiology, pathogenic mechanism, clinical manifestation, impact, diagnosis, and treatment. This newly organized information may provide helpful guidelines for physicians who treat PWE.

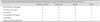

Epilepsy has bidirectional association with depression. In a matched longitudinal cohort study based on the UK General Practice Research Database, epilepsy was associated with an increased onset of depression before and after epilepsy diagnosis. This observation may suggest the presence of the common underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of epilepsy and depression.30 Depression is the most frequently occurring comorbid psychiatric disorder in epilepsy. Studies conducted in Canada, Italy, the UK, and the US have shown that the prevalence of depression was higher in PWE than in patients with other diseases or in the general population. In those studies, 9-37% of PWE met the criteria for depression (Table 1),2,3,4,5,6,16 whereas depression was observed in 9-10% of patients with other conditions6,7 and in 6-19% of the general population.8,9,10,11 Depression was also more frequent in PWE than in healthy controls in our study conducted in Korean tertiary-care hospitals; 27.8% of PWE and 8.8% of healthy controls were found to suffer from depression.14 A recent meta-analysis of population-based, original research found that the overall prevalence of active depression in PWE was 23.1%.31

The prevalence of depression in TLE was the highest among all types of epilepsy according to studies conducted in Italy and the UK.7,17 Drug-refractory epilepsy was also associated with a higher prevalence of depression. In a study conducted in two primary care practices in the UK, the frequency of depression was 33% in patients with frequent seizures and 6% in patients in remission due to AEDs.13 Patients with uncontrolled epilepsy also exhibited higher rates of depression compared with those with poorly or well-controlled epilepsy in our own previous Korean survey.14 That study found that the rates of depression in people with uncontrolled epilepsy, those with poorly controlled epilepsy, those with well-controlled epilepsy, and healthy controls were 54.3%, 23.8%, 14.0%, and 8.8%, respectively.

The matched longitudinal cohort study based on the UK General Practice Research Database also found the bidirectional association between anxiety and epilepsy.30 A Canadian population-based study found that the lifetime prevalence of anxiety was 2.4 times higher in PWE than in people without epilepsy. 5 Studies conducted in Canada, the UK, and the US have found that the prevalence of anxiety was higher in PWE than in people without epilepsy; specifically, it was 11-25% in PWE (Table 2)2,4,5,6,16 and 7-11% in people without epilepsy.5,16 Anxiety was more common in PWE than in healthy controls in our study conducted in Korean tertiary-care hospitals: the rates of anxiety were 15.3% in PWE and 3.2% in healthy controls.14

As with the prevalence of depression, previous research has found that the prevalence of anxiety in PWE is affected by the epilepsy status. The reported rate of comorbid anxiety was higher in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy and patients with TLE than in all PWE,4 and higher in patients with TLE than in patients with primary generalized epilepsy or patients with other chronic diseases.7 According to studies performed in Canada and the UK,2,15 the prevalence of anxiety was 11-44% in people with drug-refractory epilepsy, while a study from Germany found that 19 of 97 consecutive outpatients with drug-resistant epilepsy (19.6%) suffered from anxiety.32 Furthermore, anxiety was reported in 19% of patients with TLE33 and in 24.7% of epileptic surgery candidates.34 The rate of anxiety in our Korean survey was higher in patients with uncontrolled epilepsy (31.1%) than in patients with poorly controlled epilepsy (14.3%), patients with well-controlled epilepsy (6.5%), and healthy controls (3.2%).14

Depression and anxiety are frequently comorbid, and in clinical practice it is difficult to evaluate them separately since both involve negative affective symptoms.35,36 Therefore, the close relationship between depression and anxiety may be caused not only by their frequent comorbidity but also by the negative affective symptoms that they share. The importance of the comorbid occurrence of primary depression and anxiety disorders has led to specifiers for anxiety being were added to the diagnostic criteria for depressive disorders included in the fifth edition of the Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).37

Scientists have recently attempted to elucidate the pathophysiological relationship between depression and epilepsy,38 and many mechanisms for their bidirectional relationship have been suggested. Structural abnormalities, monoamine pathways, cerebral glucose metabolism, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and interleukin-1b all play a role in the common pathogenesis of these conditions. Studies that have examined depressed patients using high-resolution brain MRI have shown reductions in the volumes of various areas, including the frontal, temporal, and limbic regions. One study found that the volumes of the left and right hippocampi were significantly smaller in subjects with a history of major depression than in normal controls, and that the degree of volume reduction was correlated with the total duration of major depression.39 Given the strong association between depression and TLE found in other studies,7,17 findings of reductions in hippocampal volume suggest that depression and epilepsy reflect common structural abnormalities.39

Monoamine activity, including that associated with serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, was decreased in both depression and epilepsy.38 Among the monoamine pathways, the most plausible common pathogenic process for depression involves serotonin. The binding potential of the 5-hydroxtryptamine (serotonin)-1A (5-HT1A) receptor was reduced in various areas of the brains of depressed patients. Indeed, positron-emission tomography (PET) studies found that the 5-HT1A receptor binding potential was decreased in the frontal area, mesial temporal area, limbic cortex, and midbrain raphe of patients with depression.40 The expression level of the 5-HT1A receptor mRNA in the hippocampus was found to be reduced in a postmortem study of suicide victims with major depressive disorders.41 The role of serotonin in epilepsy was also confirmed by PET studies.42,43,44 Some PET studies found that the 5-HT1A receptor binding potential was reduced in various brain areas of patients with TLE, namely the temporal lobe, hippocampus, amygdala, anterior cingulate gyrus, insula, raphe nucleus, and thalamus. Areas with reduced 5-HT1A receptor binding potential were ipsilateral to the seizure focus, and occurred particularly in the seizure onset and propagation areas.42,43,44,45 An inverse correlation between the severity of depressive symptoms and the serotonergic effect has also been identified by PET studies of patients with TLE.43,45

Glucose metabolism was reduced in the right dorsolateral prefrontal, bilateral insular, and superior temporal areas in a PET study involving subjects with unipolar depression.46 Glucose metabolism was increased in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, right dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, and left inferior parietal cortex after 6 weeks of successful paroxetine therapy in another PET study involving male patients with major depression.47 Changes in cerebral glucose metabolism related to depression have also been investigated in PWE. Glucose hypometabolism in the bilateral inferior frontal 48 and left temporal areas 49 of patients with complex partial seizures was associated with comorbid depression. A history of preoperative depression and the development of postoperative depression were associated with glucose hypometabolism in the orbitofrontal cortex ipsilateral to the seizure focus in patients with TLE.50

High serum corticosterone levels and an overactive HPA axis have been demonstrated in a rat model of comorbid depression and TLE. The extent of HPA axis overactivity was independent of recurrent seizures, but it was positively correlated with the severity of the depressed mood.51 The sequence associated with interleukin-1b signaling can be used to explain the pathogenesis of depression in TLE. Chronic epilepsy may activate interleukin-1b signaling, which may in turn induce HPA-axis overactivity and a consequent up-regulation of 5-HT1A autoreceptors in the midbrain raphe, resulting in reduced raphe-hippocampal serotonergic transmission. The accompanying serotonergic deficit may ultimately produce depressive symptoms in TLE.52

The amygdala is essential for the experience of fear, since it induces the associated autonomic and endocrinological responses. Furthermore, the output of the amygdala to the periaqueductal gray matter is responsible for the avoidance behavior associated with fear. The hippocampus is associated with re-experiencing fear, and the symptoms of anxiety disorders reflect the activation of the fear circuit involving these structures.53,54 Similar mechanisms underlie anxiety symptoms and epilepsy, in that both involve neurons discharging excitatory currents.55 Thus, the amygdala and hippocampus play crucial pathophysiological roles in both anxiety and epilepsy. The orbitofrontal cortex, insula, and cingulate gyrus are also essential in the central mediation of anxiety.56,57,58

Inhibition of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is an important factor in the pathogenesis of anxiety.55 The GABAA receptor subtype plays a role in controlling fear arousal. Drugs that stimulate GABAA receptors, such as benzodiazepines and barbiturates, may not only increase the threshold for seizures but also control anxiety by reducing neuronal excitability.59 Pentylenetetrazole acts as a proconvulsant by blocking GABAA receptors, and also induces anxiety symptoms.60 GABAA receptor binding was reduced in patients with panic disorder (PD) in a PET study; benzodiazepine site binding was reduced throughout the brain, with the largest reductions being observed in the right orbitofrontal cortex and right insula.61

Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are effective in controlling anxiety symptoms. Since these drugs increase the concentration of serotonin in synapses, the anxiolytic effects of these drugs suggest that serotonin plays a crucial role in anxiety disorders.62 One study found that the volume distribution of 5-HT1A receptor binding was reduced in the anterior cingulate gyrus, posterior cingulate gyrus, and raphe of patients with PD.58

Modulation of calcium channels is another important factor in the pathophysiology of anxiety.55 In animal models of anxiety, calcium-channel blockers can abolish anxiety symptoms.63,64 Of the various subtypes of calcium channel, the highvoltage calcium channels, and particularly the N and P/Q types, control the release of excitatory neurotransmitters in synapses. The α2δ subunit of calcium channels controls abnormal neuronal firing in anxiety and epilepsy.59

The symptoms of depressive disorders in PWE can be classified according to their temporal relationship with seizures. Peri-ictal depressive symptoms have a temporal relationship with seizures and can be subclassified as preictal, postictal, and ictal, whereas interictal depressive symptoms have no temporal relationship with seizure occurrence.

Dysphoric mood is the most common preictal symptom of depression, which occurs between several hours and several days before the seizure. The dysphoric mood may be more severe during the 24 hours immediately preceding a seizure.65 Postictal depressive symptoms do not always occur during the same day as the seizure, and may occur up to 5 days after it.66 One study found symptoms had a median duration of was 24 hours, and the symptoms were poor frustration tolerance, loss of interest or pleasure, helplessness, irritability, feelings of self-deprecation, feelings of guilt, crying bouts, and hopelessness in order of frequency.67 Psychiatric symptoms reportedly manifest in 25% of epileptic auras, with 15% of these involving mood changes.68,69,70 Ictal depressive symptoms are usually of short duration, stereotypical, inappropriate to the situation, and associated with other ictal phenomena. The most common ictal depressive symptoms are anhedonia, guilt, and suicidal ideation.66 Interictal depressive symptoms reflect various depressive disorders, such as major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, bipolar disorder, and cyclothymic disorder.66

Major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder may be associated with similar symptoms, but they can be differentiated based on severity, persistence, and chronicity. According to DSM-5 criteria, major depressive disorder manifests as combinations of nine symptoms: depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, significant weight loss or gain, insomnia or hypersomnia, psychomotor agitation or retardation, fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt, diminished ability to think or concentrate, and recurrent thoughts of death. A diagnosis of major depressive disorder requires the depressive mood or the loss of interest or pleasure to persist for more than for 2 weeks, the presence of at least five of the nine aforementioned symptoms, and them causing significant impairment in social and occupational functioning.37 Dysthymic disorder is more chronic but less intense than major depressive disorder, the diagnosis of which requires the presence of at least two of the following symptoms for most of each day during a period of at least 2 years: poor appetite or overeating, insomnia or hypersomnia, low energy or fatigue, low self-esteem, poor concentration or difficulty making decisions, and feeling of hopelessness.37 The diagnosis of manic episodes requires the persistence of an abnormally elevated mood for more than 1 week and symptoms that markedly impair social or occupational functioning. The diagnosis of hypomanic episodes requires that an elevated mood be present for 4 consecutive days and be observable by others. There are two subtypes of bipolar disorder: type I involves manic episodes while type II involves hypomanic episodes, with both types accompanied by major depressive episodes. A cyclothymic disorder is a chronic state that involves cycling between hypomanic symptoms that do not meet the criteria for a hypomanic episode, and depressive symptoms that do not meet criteria for a major depressive episode but that persist for at least 2 years.37

The clinical symptoms of depressive disorders experienced by PWE frequently do not meet the DSM diagnostic criteria.66,71 According to one study, only 29% of depressed PWE met the criteria of the fourth edition of the DSM (DSM-IV) for major depressive disorder.71 The clinical features of the remaining 71% of patients who did not meet the DSM-IV criteria for any affective disorders included loss of interest or pleasure, fatigue, anxiety, irritability, poor frustration tolerance, and mood lability. Although these symptoms were very similar to those of dysthymic disorder, they did not meet the DSM-IV criteria because they were intermittently interrupted by symptom-free periods lasting from 1 day to several days. Therefore, this pattern of depression may be referred to as a dysthymic disorder associated with epilepsy.66 Another study found that the depressive disorders experienced by PWE tended to involve a more chronic dysthymic history and markedly fewer neurotic traits (i.e., somatization, anxiety, brooding, guilt, self-pity, hopelessness, and helplessness) than did those of nonepileptics.72

Anxiety disorders in PWE can also be classified based on the temporal correlation between symptoms and seizure occurrence. Preictal anxiety symptoms occur from several hours to several days before the seizure. The severity of the symptoms may increase as the time of the seizure approaches.62,65,73 Postictal fear occurs after a seizure and may persist for up to 7 days thereafter; such persistence is more frequent among drug-resistant patients with partial epilepsy.62,67 Anxiety symptoms almost identical to the symptoms of psychiatric disorders may occur as semiologic manifestations during the seizure. Nervousness, fear, anger, and irritability may occur as auras of seizures.4 Fear occurs as an aura among 10-15% of patients with partial seizures,74 and ictal fear is of sudden onset and brief duration.75 Seizures originating from the anteromedial area and cingulate gyrus may cause fear;74 for this reason ictal fear is closely associated with TLE.76,77 Ictal fear is more strongly associated with medial TLE than lateral TLE, occurring in 15-20% and in 10-15% of patients, respectively.77 Among the symptoms of anxiety disorders experienced by PWE, the interictal symptoms are the easiest to detect because they have no temporal relationship with seizure occurrence.78 Interictal anxiety and panic attacks occur frequently in patients with partial seizures and are closely associated with a focus in the limbic area. These symptoms may also be relatively common in patients with primary generalized epilepsy.74,75 As with depressive disorders, the clinical patterns of interictal anxiety disorders vary in PWE. These patterns include PD, general anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).79

Several factors are associated with the development of anxiety symptoms in PWE. A cross-sectional study of consecutive outpatients with epilepsy found that the use of primidone, the presence of depression, and a cryptogenic or posttraumatic etiology were significant predictors of the development of anxiety symptoms.80 The most common anxiety symptom experienced by the PWE in that study was fear, but symptoms other than fear-namely anxious mood, tension, insomnia, impaired intellectual functioning, depressed mood, and cardiovascular and genitourinary symptoms-differed between patients with and without anxiety.

The lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation was almost twice as high in PWE as in those without epilepsy in a Canadian community health survey.5 Furthermore, a population-based study found that the risk of committing suicide was three times higher among PWE than in controls,81 and was highest in PWE with comorbid psychiatric disorders; in particular, those with depression had a 32-fold higher risk of committing suicide. Suicidal ideation was more frequent among PWE with depression and/or anxiety symptoms than among PWE without these symptoms,14 and the major predictors of suicidal ideation in PWE in Korean hospital-based studies were found to be depression and other psychiatric symptoms rather than seizure-related variables.19

People with epilepsy experience stigmatization due to their epilepsy diagnosis. Nearly half of PWE in a European sample reported experiencing stigma, and high scores on the stigma scale were correlated with factors lowering the QOL such as worrying and having negative feelings about life.82 Perceived stigma was frequently associated with depression and anxiety in relation to current seizure frequency and psychosocial factors in a large community-based study in the UK.2 A US study found that the frequency of perceived stigma was greater in patients with incident epilepsy who had a lifetime history of depression or were in fair/poor health.83 A Korean hospital-based study also found that the frequency of perceived stigma was higher in PWE with depression or anxiety symptoms than in PWE without these symptoms.14

Antiepileptic drug-related adverse effects are among the main reasons for discontinuation of these medications, and AED toxicity can disrupt the daily activities of PWE. The adverse event profile of AEDs, measured using total scores on the Liverpool Adverse Event Profile (LAEP), was a major predictor of QOL in patients with well-controlled84 and drug-refractory epilepsy.85 Validation studies of the LAEP from Spain86 and Korea87 found that depression and anxiety symptoms were strongly correlated with LAEP total scores. A study of five outpatient epilepsy clinics in the US found that PWE with depression and anxiety were more likely to have worse LAEP total scores than were those without these disorders, even when these disorders were subsyndromal.26 Patients taking AEDs frequently make subjective cognitive complaints. Two hospital-based studies found that cognitive complaints were more strongly associated with depressive symptoms than with objective cognitive performance.28,29 Although various subjective complaints related to AEDs may reflect coexisting depression and anxiety symptoms, it is unclear whether objective adverse effects are also related to these symptoms. A recent Korean study measured the risk factors associated with lamotrigine-induced rash in newly diagnosed patients.27 That study applied a planned titration scheme and target doses and observed patients for 12 weeks. Patients with depressive symptoms were nine times more likely to develop a rash than were those without depressive symptoms. Other risk factors were not identified in the analyses, and so these obtained results were explained in terms of a common immune-mediated pathogenesis associated with both depression and skin rash.

Recent data revealed that one consequence of the bidirectional relationship between psychiatric disorders and epilepsy is a negative impact on responses to the pharmacological treatment of the seizure disorder. A retrospective study from the UK analyzed data from 780 patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy who had been followed over a 20-year period to investigate predictors of pharmacoresistance. Depression preceding the onset of the seizure disorder was associated with a greater-than-twofold higher risk of developing pharmacoresistant epilepsy.22 A prospective, hospital-based study conducted in Australia assessed the neuropsychiatric symptomatology of 138 newly diagnosed patients before they started AEDs.23 The seizure-free frequency after 12 months was lower for patients with higher pretreatment scores on the A-B Neuropsychological Assessment Scale (ABNAS). Another study found that ABNAS scores were correlated with anxiety and depression.88

A lifetime history of psychiatric disorders also appears to be related to poor postsurgical outcomes. A UK study that reviewed the medical records of 280 patients who underwent TLE surgery, found that patients with a preoperative psychiatric diagnosis were significantly less likely to remain seizure free (OR=0.53, 95% CI=0.28-0.98, p=0.04).24 A presurgical history of major depressive disorder (OR=5.23, p=0.003) was the most important risk factor associated with a nonfavorable seizure outcome after corticoamygdalohippocampectomy in another study investigating 115 patients with refractory TLE and mesial temporal sclerosis.25

The QOL tends to be worse in PWE than in the general population, not only because of seizures but also because of concurrent medical, psychiatric, and psychosocial problems.89 Specifically, several recent studies have shown that depression and anxiety symptoms were the major determinants of QOL. A study of patients with TLE in the US found that interictal anxiety and depressive symptoms accounted for more of the variance in QOL than did seizure frequency, severity, or chronicity.90 Among seizure-related, medical, AED-related, and psychiatric factors in a Korean hospital-based study, the strongest predictors of QOL were depression and anxiety, followed by seizure control.91 Indeed, the QOL was significantly better in patients with drug-refractory epilepsy without comorbid depression and anxiety symptoms than in patients with 1 year of seizure freedom but with such symptoms. Patients with coexisting depression and anxiety were more likely to have a poor QOL than were those with only one of these conditions.14 Thus, the authors recommended that clinicians should always consider the coexistence of depression and anxiety in each PWE and screen for both types of symptom simultaneously so as to prevent impairments in QOL.

The adverse events associated with AEDs can affect the extent to which depression affects QOL. The impact of depressive symptoms on QOL was 3.37 times higher than that of LAEP total scores in a Korean study conducted with patients with well-controlled epilepsy on monotherapy.84 However, the contribution of LAEP total scores to QOL was slightly greater than that of depressive symptoms in an Italian multicenter study conducted with patients with drug-refractory epilepsy.85 Thus, the burden of drug toxicity appears to be greater in those patients.

While identifying depression and anxiety is important for the ensuring the most appropriate management of PWE, these conditions have generally been neglected in outpatient neurology clinics due to the busyness of these settings and the lack of brief, self-administered screening tools specifically designed for PWE.92 Although comorbid depression and anxiety in PWE can be measured in structured psychiatric interviews, such as those employing the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV axis I Disorders93 and the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI),94 these take a long time to complete. Therefore, rapid screening tests to identify depression or anxiety in busy clinical settings are currently being developed and validated.

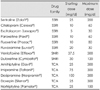

The most popular screening test for depression in PWE is the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E), which is a brief, six-item questionnaire that was developed and validated in the US as a screening tool for depression in PWE.95 The six items are rated on a 4-point scale from 1 to 4, and so the total score ranges from 6 to 24, with a higher score indicating a higher level of depression. This instrument takes less than 3 minutes to complete, and a cutoff score of 15 is suggestive of a major depressive episode that would mandate referral to a psychiatrist for further evaluation. Seven recent studies aimed at validating the NDDI-E in different languages (i.e., Brazilian Portuguese, Italian, Spanish, Japanese, German, Korean, and Greek) also found that the questionnaire was easy to administer and that its levels of reliability and validity were similar to those of the original version.96,97,98,99,100,101,102 The Korean version of the NDDI-E (K-NDDI-E) is presented in Table 3. Interestingly, the cutoff score for the validated instrument differed with its language: it was lowest (i.e., >11) for the K-NDDI-E, and highest (i.e., >16) for the Japanese NDDI-E. Therefore, further validation studies should be conducted in other countries in their respective native languages.

Clinicians who are too busy to use the NDDI-E to screen for depression can use the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) instead. A validation study of the NDDI-E and the PHQ-2 among PWE using the MINI in a primary-care setting found that the sensitivity and specificity were 80% and 100%, respectively, for the PHQ-2, and 100% and 85% for the NDDIE, suggesting that the two instruments are comparable.103

Unfortunately, there are currently no specific screening instruments to identify anxiety in PWE; however, the standardized clinical tools used to assess anxiety in psychiatric settings can be employed. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, a self-report scale measuring anxiety and depressive symptoms, was developed to investigate various dimensions of mood in patients with medical comorbidities.104 It includes anxiety (seven items) and depression (seven items) subscales, and the total score ranges from 0 to 21, with a higher score reflecting a worse psychiatric status. Subscale scores of >8 represent pathological levels of anxiety and depression.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) is a recently introduced self-report questionnaire that addresses whether individuals have been bothered by anxiety-related problems during the previous 2 weeks. It includes questions that are scored on a 4-point scale from 0 to 3, with the total score ranging from 0 to 21 and a higher score indicating a higher level of anxiety.105 It requires less than 3 minutes to complete, and a score >9 supports a diagnosis of GAD. This instrument has been widely used by general practitioners106 and can be used to screen for GAD in PWE because it contains only seven items that address somatic symptoms that can be confused with the adverse effects of AEDs, the cognitive symptoms of the seizure disorder, or the underlying neurologic disorder associated with epilepsy.107 Recently, the validation of GAD-7 was performed in Korean PWE.108 A score >6 supported a diagnosis of GAD. The impact of adverse effects of AEDs on the GAD-7 was less than that on the K-NDDI-E.

Depression and anxiety symptoms are gradually being recognized as important aspects of PWE. However, there is currently insufficient information about how to manage these conditions. In addition, neither patients nor physicians seem to be sufficiently concerned about depression and anxiety in PWE. Concerns that psychotropic drugs may aggravate seizures also lead some physicians to resist prescribing these drugs. To overcome these limitations, physicians must be provided with practical information about depression and anxiety in PWE. This information should make it easier for physicians to address the treatment of depression and anxiety in PWE.

Depression and anxiety are closely associated with each other, and they coexist in many PWE.14,109 Thus, amelioration of the symptoms of depression or anxiety is quite likely to reduce the symptoms of the other condition. One study found that 13% of patients in a general medical clinic exhibited symptoms of depression, and 67% of this group had moderate comorbid anxiety, the severity of which decreased in patients whose depression decreased after a follow-up period of 1 year.110

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) developed the international consensus clinical practice statements for the treatment of neuropsychiatric conditions associated with epilepsy.111 The purpose of these statements was to facilitate the appropriate management of various neuropsychiatric disorders in PWE. We extracted several elements from these statements for use as guidelines for the management of depression and anxiety in PWE.

Screening methods are helpful for the evaluation and management of depressive disorders. The international statements recommend use of the NDDI-E or PHQ-2 for this purpose. They also recommend that all newly diagnosed PWE be screened on an annual basis. Even when PWE experience only mild depressive disorder, this should be managed without delay. The statements also recommend that supportive psychotherapy be provided to newly diagnosed PWE and their families by trained professionals or specialists. In terms of pharmacological management, when available, SSRIs are considered first-line drugs because they are unlikely to provoke seizures and favorable adverse-effects profiles. To prevent adverse effects, antidepressants should be started at low doses, and titrated upwards in small increments until the desired clinical response is achieved.

The statements recommend that antidepressant therapy continue for 6 months after recovery from the first depressive episode and for at least 2 years after recovery from the second and/or subsequent episode(s). Clinicians should be aware that SSRIs such as fluoxetine and fluvoxamine may inhibit hepatic enzymes and consequently increase the serum levels of AEDs. They should also be aware that discontinuation of AEDs having positive psychotropic effects may provoke depression.111

The ILAE statements underscore the need for clinicians to be aware of the frequent comorbidity of anxiety disorders in PWE. When anxiety and depression are simultaneously present in PWE, the clinical course and treatment response are worse than when either anxiety or depression is present as the sole condition. The same pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments used for people without epilepsy are also effective in PWE.

Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and serotonin and norepinephrine-reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are considered the first-line therapy for depression in PWE (Table 4). A drug from the other family should be used when a trial of an SSRI or SNRI at the adequate dose fails to control the symptoms.112 SSRIs are unlikely to elicit the proconvulsant effects associated with other families of antidepressants, and so they are preferentially selected for the control of depression in PWE. Moreover, SSRIs are less to elicit other side effects and are more tolerable at high doses compared with other antidepressants. Among SSRIs, sertraline and citalopram have fewer pharmacokinetic interactions with AEDs. In general, sertraline can be preferentially selected for the treatment of depression in PWE because it is safe to use in this population.71 However, a tolerance for sertraline that interferes with its therapeutic effects may develop over time in some patients. In such cases, citalopram can be substituted in PWE.113,114 It has been reported that administering citalopram to PWE at 10-40 mg/day for 2 months114 or 20 mg/day for 4 months115 to treat depression did not increase the seizure frequency. Furthermore, the use of citalopram at 20 mg/day as an add-on to AEDs even reduced the seizure frequency in nondepressed patients with poorly controlled epilepsy.116

Venlafaxine is an SNRI and thus acts on both serotonergic and norepinephrinergic neurotransmitters. This can be another effective option for the treatment of depression in PWE when SSRIs are not effective.113 There are anecdotal reports of 75-225 mg/day of venlafaxine improving depressive symptoms without aggravating seizures in patients with partial epilepsy, which suggests that venlafaxine can be safely used in patients with partial epilepsy.38 The extended-release preparation of venlafaxine can be prescribed once per day; this preparation is therefore helpful for cognitively impaired PWE who have difficulty following complex medication regimens.

When using SSRIs and SNRIs, it should be noted that the therapeutic effect may not manifest during the first 3-6 weeks after starting of the drugs. In addition, SSRIs can sometimes cause restlessness and mild anxiety at the start of therapy. In those cases, a short course of a benzodiazepine may be helpful.112 When SSRIs and SNRIs are not available, TCAs are the drug of choice for depression in PWE (Table 4). However, since TCAs have exhibit more side effects and are associated with cardiac toxicity in overdoses, it is recommended that plasma drug levels be monitored and interactions with other concomitant drugs be considered when TCAs are used.112,113 Two studies using the TCA doxepine provided evidence that antidepressants may improve seizure control in PWE.117,118

A meta-analysis showed that treatment with antidepressants or certain AEDs along with behavioral treatments improved both depression and seizures in PWE with comorbid depression.119 Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can alleviate depression in PWE,120 and a combination of psychotherapy and medication has been shown to be more effective than medication alone for the treatment of depression.121

Antidepressants such as SSRIs and SNRIs have been shown to be effective against both anxiety and depression.109 CBT is also effective against anxiety and should be considered for the management of anxiety disorders in PWE.79,120 The appropriate treatment protocols differ slightly with the clinical pattern of the specific anxiety disorder experienced by PWE.79

Combined treatment with SSRIs and CBT is indicated in the acute phase of PD. In terms of long-term maintenance treatment, a combined approach or CBT alone may be appropriate. Both antidepressants and benzodiazepine can be used for the pharmacological management of PD. Antidepressants are at least equally as effective as benzodiazepine for the management of anxiety associated with PD.122,123,124,125 Benzodiazepines are not superior to antidepressants for managing the depressive symptoms that may accompany PD.125

Common treatment options for GAD also include CBT, SSRIs, SNRIs, benzodiazepines, azapirones (e.g., buspirone), antihistamines (e.g., hydroxyzine), and pregabalin. Pregabalin is an AED that can be the drug of first choice for both the long-term55 and short-term management55,126 of GAD in PWE. Pregabalin is also effective in ameliorating comorbid depression in GAD.127 A meta-analysis has revealed the efficacy of antidepressants such as imipramine, venlafaxine, and paroxetine for GAD.128

In terms of SAD, SSRIs such as sertraline and paroxetine can be considered first-line treatment options.79 A Cochrane review found that various drugs, including SSRIs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A (RIMAs), benzodiazepines, and gabapentin, were beneficial for the short-term management of SAD. SSRIs were more effective than RIMAs and decreased not only the symptom cluster of SAD but also comorbid depressive symptoms and associated disability.129,130 SSRIs are also considered first-line drugs for PTSD.79,131 Paroxetine and sertraline are the preferred SSRIs for reducing the severity of PTSD symptoms.132 CBT is a first-line treatment option for the management of mild-to-moderate OCD.133 Pharmacotherapy should be applied when severe symptoms remain even after CBT treatment or when the symptoms of OCD are severe.134 CBT is also always considered a first-line treatment for the management of OCD in PWE. As in the general population, drug treatments are needed when the therapeutic effect of CBT is insufficient in PWE with OCD. SSRIs, and particularly sertraline, are preferred for the pharmacological management of OCD.

Many physicians are concerned about antidepressants inducing seizures in nonepileptic patients.135 The proconvulsant effects of antidepressants may be enhanced by factors such as high serum concentrations and rapid dose escalations.74,136 Antidepressants should therefore be started at low doses and increased in small increments when applied to PWE. The individual characteristics of specific patients may also affect the likelihood of proconvulsant effects of antidepressants. It has been demonstrated that increased proconvulsant effects in PWE are associated with CNS pathology, electroencephalographic abnormalities, a personal or family history of epilepsy, and comorbid behavioral disturbances.74,136 Bupropion, maprotiline, and amoxapine are antidepressants with intense proconvulsant effects, and they should therefore be avoided in PWE.112,137,138,139,140 TCAs may exert a proconvulsant effect, and clomipramine has been frequently associated with an increased risk of seizures.112 However, there is no evidence that seizures can be provoked by TCAs when they are used at or below therapeutic plasma levels. Slow drug metabolism was reported in cases in which seizures were induced by TCAs at therapeutic plasma levels.136 Thus, high plasma levels are important contributors to seizures provoked by TCAs.136 For this reason, TCAs that can be maintained at therapeutic plasma levels may be a useful option for the management of the depressive symptoms of PWE (Table 4).113,141,142

Antiepileptic drugs are associated with several psychiatric problems due to the mechanisms of action underlying their antiepileptic activity. AEDs can be divided into two categories according to their psychotropic properties: 1) sedating or GABAergic drugs, and 2) activating or antiglutamatergic drugs.143 This classification is straightforward but can only partly explain the adverse psychiatric events of AEDs, which are also associated with indirect mechanisms due to their interaction with the underlying epileptic process. The positive and negative psychotropic properties of AEDs have been well summarized in a review article.144 Phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproate, lamotrigine, and oxcarbazepine are known to have a mood-stabilizing effect, and hence these drugs are recommended for the treatment of mood lability or bipolar disorder in PWE. Lamotrigine is also recommended for the treatment of depression.

Benzodiazepines, gabapentin, and pregabalin can be used to treat anxiety in PWE, whereas barbiturates, vigabatrin, zonisamide, topiramate, tiagabine, and pregabalin may produce mood changes and are therefore not recommended for use in depressed patients. Lamotrigine, felbamate, and tiagabine may induce anxiety, irritability, and aggression, and so are not recommended for use in anxious patients. Levetiracetam is the most widely used AED in Korean PWE due to its high efficacy and low toxicity. However, it has been known to elicit irritability, aggression, depression, anxiety, and sometimes even suicidal ideation or attempts. Risk factors for developing adverse psychiatric problems with levetiracetam include a history of febrile convulsions, status epilepticus, or psychiatric problems145,146 A recent study found an association between genetic variations in dopaminergic activity and the risk for adverse psychiatric effects during levetiracetam therapy.147

Similar to the proportion of PWE with drug-refractory epilepsy, almost one-third of PWE suffer from depression and anxiety, but these conditions are often underrecognized and undertreated by clinicians. These psychiatric problems are likely to produce suicidal ideation or attempts, perceived stigmatization, adverse effects associated with AEDs, worse responses to pharmacological and surgical treatments of the seizure disorder, and a worse QOL. Therefore, clinicians should evaluate PWE for depression and anxiety using simple screening instruments that are able to rapidly detect symptoms of these disorders in busy clinical settings. Although a systematic review of the published literature identified methodological limitations in studies investigating treatments for depression and anxiety in PWE, it also provided evidence that both medication and psychotherapy alleviate these conditions.119 However, randomized controlled trials are needed to determine the most appropriate pharmacological and psychobehavioral treatments for depression and anxiety in PWE.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Prevalence or frequency of depression by community-based and hospital-based studies in people with epilepsy

*2004 HealthStyles survey.

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, CES-D: Center for Epidemiology Studies-Depression Scale, GPRD: General Practice Research Database in England and Wales, HAD: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, PWE: people with epilepsy, WHM-CIDI: World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

References

2. Jacoby A, Baker GA, Steen N, Potts P, Chadwick DW. The clinical course of epilepsy and its psychosocial correlates: findings from a U.K. Community study. Epilepsia. 1996; 37:148–161.

3. Ettinger A, Reed M, Cramer J. Epilepsy Impact Project Group. Depression and comorbidity in community-based patients with epilepsy or asthma. Neurology. 2004; 63:1008–1014.

4. Gaitatzis A, Trimble MR, Sander JW. The psychiatric comorbidity of epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004; 110:207–220.

5. Tellez-Zenteno JF, Patten SB, Jetté N, Williams J, Wiebe S. Psychiatric comorbidity in epilepsy: a population-based analysis. Epilepsia. 2007; 48:2336–2344.

6. Gaitatzis A, Carroll K, Majeed A, W Sander J. The epidemiology of the comorbidity of epilepsy in the general population. Epilepsia. 2004; 45:1613–1622.

7. Perini GI, Tosin C, Carraro C, Bernasconi G, Canevini MP, Canger R, et al. Interictal mood and personality disorders in temporal lobe epilepsy and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996; 61:601–605.

8. Regier DA, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, Blazer DG, Hough RL, et al. The NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area program. Historical context, major objectives, and study population characteristics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984; 41:934–941.

9. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993; 50:85–94.

10. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994; 51:8–19.

11. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62:617–627.

12. Sillanpää M, Schmidt D. Natural history of treated childhood-onset epilepsy: prospective, long-term population-based study. Brain. 2006; 129(Pt 3):617–624.

13. O'Donoghue MF, Goodridge DM, Redhead K, Sander JW, Duncan JS. Assessing the psychosocial consequences of epilepsy: a community-based study. Br J Gen Pract. 1999; 49:211–214.

14. Kwon OY, Park SP. Frequency of affective symptoms and their psychosocial impact in Korean people with epilepsy: a survey at two tertiary care hospitals. Epilepsy Behav. 2013; 26:51–56.

15. Manchanda R, Schaefer B, McLachlan RS, Blume WT, Wiebe S, Girvin JP, et al. Psychiatric disorders in candidates for surgery for epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996; 61:82–89.

16. Kobau R, Gilliam F, Thurman DJ. Prevalence of self-reported epilepsy or seizure disorder and its associations with self-reported depression and anxiety: results from the 2004 HealthStyles Survey. Epilepsia. 2006; 47:1915–1921.

17. Edeh J, Toone B. Relationship between interictal psychopathology and the type of epilepsy. Results of a survey in general practice. Br J Psychiatry. 1987; 151:95–101.

18. Jones JE, Hermann BP, Barry JJ, Gilliam FG, Kanner AM, Meador KJ. Rates and risk factors for suicide, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts in chronic epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2003; 4:Suppl 3. S31–S38.

19. Lim HW, Song HS, Hwang YH, Lee HW, Suh CK, Park SP, et al. Predictors of suicidal ideation in people with epilepsy living in Korea. J Clin Neurol. 2010; 6:81–88.

20. Jacoby A. Felt versus enacted stigma: a concept revisited. Evidence from a study of people with epilepsy in remission. Soc Sci Med. 1994; 38:269–274.

21. Taylor J, Baker GA, Jacoby A. Levels of epilepsy stigma in an incident population and associated factors. Epilepsy Behav. 2011; 21:255–260.

22. Hitiris N, Mohanraj R, Norrie J, Sills GJ, Brodie MJ. Predictors of pharmacoresistant epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2007; 75:192–196.

23. Petrovski S, Szoeke CE, Jones NC, Salzberg MR, Sheffield LJ, Huggins RM, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptomatology predicts seizure recurrence in newly treated patients. Neurology. 2010; 75:1015–1021.

24. Cleary RA, Thompson PJ, Fox Z, Foong J. Predictors of psychiatric and seizure outcome following temporal lobe epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. 2012; 53:1705–1712.

25. de Araújo Filho GM, Gomes FL, Mazetto L, Marinho MM, Tavares IM, Caboclo LO, et al. Major depressive disorder as a predictor of a worse seizure outcome one year after surgery in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy and mesial temporal sclerosis. Seizure. 2012; 21:619–623.

26. Kanner AM, Barry JJ, Gilliam F, Hermann B, Meador KJ. Depressive and anxiety disorders in epilepsy: do they differ in their potential to worsen common antiepileptic drug-related adverse events? Epilepsia. 2012; 53:1104–1108.

27. Park SP. Depression in patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy predicts lamotrigine-induced rash: a short-term observational study. Epilepsy Behav. 2013; 28:88–90.

28. Liik M, Vahter L, Gross-Paju K, Haldre S. Subjective complaints compared to the results of neuropsychological assessment in patients with epilepsy: The influence of comorbid depression. Epilepsy Res. 2009; 84:194–200.

29. Marino SE, Meador KJ, Loring DW, Okun MS, Fernandez HH, Fessler AJ, et al. Subjective perception of cognition is related to mood and not performance. Epilepsy Behav. 2009; 14:459–464.

30. Hesdorffer DC, Ishihara L, Mynepalli L, Webb DJ, Weil J, Hauser WA. Epilepsy, suicidality, and psychiatric disorders: a bidirectional association. Ann Neurol. 2012; 72:184–191.

31. Fiest KM, Dykeman J, Patten SB, Wiebe S, Kaplan GG, Maxwell CJ, et al. Depression in epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2013; 80:590–599.

32. Brandt C, Schoendienst M, Trentowska M, May TW, Pohlmann-Eden B, Tuschen-Caffier B, et al. Prevalence of anxiety disorders in patients with refractory focal epilepsy--a prospective clinic based survey. Epilepsy Behav. 2010; 17:259–263.

33. Currie S, Heathfield KW, Henson RA, Scott DF. Clinical course and prognosis of temporal lobe epilepsy. A survey of 666 patients. Brain. 1971; 94:173–190.

34. Devinsky O, Barr WB, Vickrey BG, Berg AT, Bazil CW, Pacia SV, et al. Changes in depression and anxiety after resective surgery for epilepsy. Neurology. 2005; 65:1744–1749.

35. Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991; 100:316–336.

36. Olino TM, Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Longitudinal associations between depressive and anxiety disorders: a comparison of two trait models. Psychol Med. 2008; 38:353–363.

37. American Psychiatric Association. Bipolar and related disorders. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association;2013. p. 123–188.

38. Kanner AM, Balabanov A. Depression and epilepsy: how closely related are they? Neurology. 2002; 58:8 Suppl 5. S27–S39.

39. Sheline YI, Wang PW, Gado MH, Csernansky JG, Vannier MW. Hippocampal atrophy in recurrent major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996; 93:3908–3913.

40. Drevets WC, Frank E, Price JC, Kupfer DJ, Holt D, Greer PJ, et al. PET imaging of serotonin 1A receptor binding in depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1999; 46:1375–1387.

41. López JF, Chalmers DT, Little KY, Watson SJ. A.E. Bennett Research Award. Regulation of serotonin1A, glucocorticoid, and mineralocorticoid receptor in rat and human hippocampus: implications for the neurobiology of depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1998; 43:547–573.

42. Toczek MT, Carson RE, Lang L, Ma Y, Spanaki MV, Der MG, et al. PET imaging of 5-HT1A receptor binding in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 2003; 60:749–756.

43. Savic I, Lindström P, Gulyás B, Halldin C, Andrée B, Farde L. Limbic reductions of 5-HT1A receptor binding in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 2004; 62:1343–1351.

44. Merlet I, Ostrowsky K, Costes N, Ryvlin P, Isnard J, Faillenot I, et al. 5-HT1A receptor binding and intracerebral activity in temporal lobe epilepsy: an [18F]MPPF-PET study. Brain. 2004; 127(Pt 4):900–913.

45. Hasler G, Bonwetsch R, Giovacchini G, Toczek MT, Bagic A, Luckenbaugh DA, et al. 5-HT1A receptor binding in temporal lobe epilepsy patients with and without major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2007; 62:1258–1264.

46. Kimbrell TA, Ketter TA, George MS, Little JT, Benson BE, Willis MW, et al. Regional cerebral glucose utilization in patients with a range of severities of unipolar depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2002; 51:237–252.

47. Kennedy SH, Evans KR, Krüger S, Mayberg HS, Meyer JH, McCann S, et al. Changes in regional brain glucose metabolism measured with positron emission tomography after paroxetine treatment of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001; 158:899–905.

48. Bromfield EB, Altshuler L, Leiderman DB, Balish M, Ketter TA, Devinsky O, et al. Cerebral metabolism and depression in patients with complex partial seizures. Arch Neurol. 1992; 49:617–623.

49. Victoroff JI, Benson F, Grafton ST, Engel J Jr, Mazziotta JC. Depression in complex partial seizures. Electroencephalography and cerebral metabolic correlates. Arch Neurol. 1994; 51:155–163.

50. Salzberg M, Taher T, Davie M, Carne R, Hicks RJ, Cook M, et al. Depression in temporal lobe epilepsy surgery patients: an FDG-PET study. Epilepsia. 2006; 47:2125–2130.

51. Mazarati AM, Shin D, Kwon YS, Bragin A, Pineda E, Tio D, et al. Elevated plasma corticosterone level and depressive behavior in experimental temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis. 2009; 34:457–461.

52. Pineda E, Shin D, Sankar R, Mazarati AM. Comorbidity between epilepsy and depression: experimental evidence for the involvement of serotonergic, glucocorticoid, and neuroinflammatory mechanisms. Epilepsia. 2010; 51:Suppl 3. 110–114.

53. Stahl SM. Brainstorms: symptoms and circuits, part 2: anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003; 64:1408–1409.

54. Rogawski MA, Löscher W. The neurobiology of antiepileptic drugs for the treatment of nonepileptic conditions. Nat Med. 2004; 10:685–692.

55. Mula M, Pini S, Cassano GB. The role of anticonvulsant drugs in anxiety disorders: a critical review of the evidence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007; 27:263–272.

56. Rauch SL, Savage CR, Alpert NM, Miguel EC, Baer L, Breiter HC, et al. A positron emission tomographic study of simple phobic symptom provocation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995; 52:20–28.

57. Vermetten E, Schmahl C, Southwick SM, Bremner JD. Positron tomographic emission study of olfactory induced emotional recall in veterans with and without combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2007; 40:8–30.

58. Neumeister A, Bain E, Nugent AC, Carson RE, Bonne O, Luckenbaugh DA, et al. Reduced serotonin type 1A receptor binding in panic disorder. J Neurosci. 2004; 24:589–591.

59. Mula M, Monaco F. Antiepileptic drugs and psychopathology of epilepsy: an update. Epileptic Disord. 2009; 11:1–9.

60. Jung ME, Lal H, Gatch MB. The discriminative stimulus effects of pentylenetetrazol as a model of anxiety: recent developments. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002; 26:429–439.

61. Malizia AL, Cunningham VJ, Bell CJ, Liddle PF, Jones T, Nutt DJ. Decreased brain GABA(A)-benzodiazepine receptor binding in panic disorder: preliminary results from a quantitative PET study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998; 55:715–720.

62. Kanner AM, Ettinger AB. Anxiety disorders. In : Engel J, Pedley TA, editors. Epilepsy: a Comprehensive Textbook. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2008. p. 2139–2154.

63. Chugh Y, Saha N, Sankaranarayanan A, Sharma PL. Effect of peripheral administration of cinnarizine and verapamil on the abstinence syndrome in diazepam-dependent rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1992; 106:127–130.

64. Saad SF, Khayyal MT, Attia AS, Saad ES. Influence of certain calcium-channel blockers on some aspects of lorazepam-dependence in mice. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1997; 49:322–328.

65. Blanchet P, Frommer GP. Mood change preceding epileptic seizures. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986; 174:471–476.

66. Kanner AM, Blumer D. Affective disorders. In : Engel J, Pedley TA, editors. Epilepsy: a Comprehensive Textbook. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2008. p. 2123–2138.

67. Kanner AM, Soto A, Gross-Kanner H. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of postictal psychiatric symptoms in partial epilepsy. Neurology. 2004; 62:708–713.

69. Weil AA. Depressive reactions associated with temporal lobe-uncinate seizure. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1955; 121:505–510.

70. Williams D. The structure of emotions reflected in epileptic experiences. Brain. 1956; 79:29–67.

71. Kanner AM, Kozak AM, Frey M. The Use of Sertraline in Patients with Epilepsy: Is It Safe? Epilepsy Behav. 2000; 1:100–105.

72. Mendez MF, Cummings JL, Benson DF. Depression in epilepsy. Significance and phenomenology. Arch Neurol. 1986; 43:766–770.

73. Hughes J, Devinsky O, Feldmann E, Bromfield E. Premonitory symptoms in epilepsy. Seizure. 1993; 2:201–203.

74. Torta R, Keller R. Behavioral, psychotic, and anxiety disorders in epilepsy: etiology, clinical features, and therapeutic implications. Epilepsia. 1999; 40:Suppl 10. S2–S20.

75. Devinsky O, Vazquez B. Behavioral changes associated with epilepsy. Neurol Clin. 1993; 11:127–149.

76. Gloor P, Olivier A, Quesney LF, Andermann F, Horowitz S. The role of the limbic system in experiential phenomena of temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 1982; 12:129–144.

77. Devinsky O. A 48-year-old man with temporal lobe epilepsy and psychiatric illness. JAMA. 2003; 290:381–392.

78. Hermann BP, Chhabria S. Interictal psychopathology in patients with ictal fear. Examples of sensory-limbic hyperconnection? Arch Neurol. 1980; 37:667–668.

79. Mula M. Treatment of anxiety disorders in epilepsy: an evidencebased approach. Epilepsia. 2013; 54:Suppl 1. 13–18.

80. López-Gómez M, Espinola M, Ramirez-Bermudez J, Martinez-Juarez IE, Sosa AL. Clinical presentation of anxiety among patients with epilepsy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008; 4:1235–1239.

81. Christensen J, Vestergaard M, Mortensen PB, Sidenius P, Agerbo E. Epilepsy and risk of suicide: a population-based case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2007; 6:693–698.

82. Baker GA, Brooks J, Buck D, Jacoby A. The stigma of epilepsy: a European perspective. Epilepsia. 2000; 41:98–104.

83. Leaffer EB, Jacoby A, Benn E, Hauser WA, Shih T, Dayan P, et al. Associates of stigma in an incident epilepsy population from northern Manhattan, New York City. Epilepsy Behav. 2011; 21:60–64.

84. Kwon OY, Park SP. What is the role of depressive symptoms among other predictors of quality of life in people with well-controlled epilepsy on monotherapy? Epilepsy Behav. 2011; 20:528–532.

85. Luoni C, Bisulli F, Canevini MP, De Sarro G, Fattore C, Galimberti CA, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life in pharmacoresistant epilepsy: results from a large multicenter study of consecutively enrolled patients using validated quantitative assessments. Epilepsia. 2011; 52:2181–2191.

86. Carreño M, Donaire A, Falip M, Maestro I, Fernández S, Nagel AG, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the Liverpool Adverse Events Profile in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2009; 15:154–159.

87. Park JM, Seo JG, Park SP. Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the Liverpool Adverse Events Profile (K-LAEP) in people with epilepsy. J Korean Epilepsy Soc. 2012; 16:43–48.

88. Brooks J, Baker GA, Aldenkamp AP. The A-B neuropsychological assessment schedule (ABNAS): the further refinement of a patientbased scale of patient-perceived cognitive functioning. Epilepsy Res. 2001; 43:227–237.

89. Jacoby A, Snape D, Baker GA. Determinants of quality of life in people with epilepsy. Neurol Clin. 2009; 27:843–863.

90. Johnson EK, Jones JE, Seidenberg M, Hermann BP. The relative impact of anxiety, depression, and clinical seizure features on health-related quality of life in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2004; 45:544–550.

91. Park SP, Song HS, Hwang YH, Lee HW, Suh CK, Kwon SH. Differential effects of seizure control and affective symptoms on quality of life in people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2010; 18:455–459.

92. Friedman DE, Kung DH, Laowattana S, Kass JS, Hrachovy RA, Levin HS. Identifying depression in epilepsy in a busy clinical setting is enhanced with systematic screening. Seizure. 2009; 18:429–433.

93. Jones JE, Hermann BP, Barry JJ, Gilliam F, Kanner AM, Meador KJ. Clinical assessment of Axis I psychiatric morbidity in chronic epilepsy: a multicenter investigation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005; 17:172–179.

94. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998; 59:Suppl 20. 22–33. quiz 34-57.

95. Gilliam FG, Barry JJ, Hermann BP, Meador KJ, Vahle V, Kanner AM. Rapid detection of major depression in epilepsy: a multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2006; 5:399–405.

96. de Oliveira GN, Kummer A, Salgado JV, Portela EJ, Sousa-Pereira SR, David AS, et al. Brazilian version of the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E). Epilepsy Behav. 2010; 19:328–331.

97. Mula M, Iudice A, La Neve A, Mazza M, Bartolini E, De Caro MF, et al. Validation of the Italian version of the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E). Epilepsy Behav. 2012; 24:329–331.

98. Di Capua D, Garcia-Garcia ME, Reig-Ferrer A, Fuentes-Ferrer M, Toledano R, Gil-Nagel A, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E). Epilepsy Behav. 2012; 24:493–496.

99. Tadokoro Y, Oshima T, Fukuchi T, Kanner AM, Kanemoto K. Screening for major depressive episodes in Japanese patients with epilepsy: validation and translation of the Japanese version of Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E). Epilepsy Behav. 2012; 25:18–22.

100. Metternich B, Wagner K, Buschmann F, Anger R, Schulze-Bonhage A. Validation of a German version of the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E). Epilepsy Behav. 2012; 25:485–488.

101. Ko PW, Hwang J, Lim HW, Park SP. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (K-NDDI-E). Epilepsy Behav. 2012; 25:539–542.

102. Zis P, Yfanti P, Siatouni A, Tavernarakis A, Gatzonis S. Validation of the Greek version of the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E). Epilepsy Behav. 2013; 29:513–515.

103. Margrove K, Mensah S, Thapar A, Kerr M. Depression screening for patients with epilepsy in a primary care setting using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 and the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2011; 21:387–390.

104. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983; 67:361–370.

105. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166:1092–1097.

106. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007; 146:317–325.

107. Kanner AM. Anxiety disorders in epilepsy: the forgotten psychiatric comorbidity. Epilepsy Curr. 2011; 11:90–91.

108. Seo JG, Cho YW, Lee SJ, Lee JJ, Kim JE, Moon HJ, et al. Validation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 in people with epilepsy: A MEPSY study. Epilepsy Behav. 2014; 35:59–63.

109. Kanner AM. Psychiatric issues in epilepsy: the complex relation of mood, anxiety disorders, and epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2009; 15:83–87.

110. Zung WW, Magruder-Habib K, Velez R, Alling W. The comorbidity of anxiety and depression in general medical patients: a longitudinal study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990; 51:Suppl. 77–80. discussion 81.

111. Kerr MP, Mensah S, Besag F, de Toffol B, Ettinger A, Kanemoto K, et al. International consensus clinical practice statements for the treatment of neuropsychiatric conditions associated with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2011; 52:2133–2138.

112. Kanner AM. The treatment of depressive disorders in epilepsy: what all neurologists should know. Epilepsia. 2013; 54:Suppl 1. 3–12.

113. Barry JJ, Ettinger AB, Friel P, Gilliam FG, Harden CL, Hermann B, et al. Consensus statement: the evaluation and treatment of people with epilepsy and affective disorders. Epilepsy Behav. 2008; 13:Suppl 1. S1–S29.

114. Hovorka J, Herman E, Nemcová I. Treatment of Interictal Depression with Citalopram in Patients with Epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2000; 1:444–447.

115. Specchio LM, Iudice A, Specchio N, La Neve A, Spinelli A, Galli R, et al. Citalopram as treatment of depression in patients with epilepsy. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004; 27:133–136.

116. Favale E, Audenino D, Cocito L, Albano C. The anticonvulsant effect of citalopram as an indirect evidence of serotonergic impairment in human epileptogenesis. Seizure. 2003; 12:316–318.

117. Ojemann LM, Friel PN, Trejo WJ, Dudley DL. Effect of doxepin on seizure frequency in depressed epileptic patients. Neurology. 1983; 33:646–648.

118. Ojemann LM, Baugh-Bookman C, Dudley DL. Effect of psychotropic medications on seizure control in patients with epilepsy. Neurology. 1987; 37:1525–1527.

119. Mehndiratta P, Sajatovic M. Treatments for patients with comorbid epilepsy and depression: a systematic literature review. Epilepsy Behav. 2013; 28:36–40.

120. Macrodimitris S, Wershler J, Hatfield M, Hamilton K, Backs-Dermott B, Mothersill K, et al. Group cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with epilepsy and comorbid depression and anxiety. Epilepsy Behav. 2011; 20:83–88.

121. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L, Andersson G. Psychotherapy versus the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2009; 26:279–288.

122. Wilkinson G, Balestrieri M, Ruggeri M, Bellantuono C. Meta-analysis of double-blind placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants and benzodiazepines for patients with panic disorders. Psychol Med. 1991; 21:991–998.

123. Boyer W. Serotonin uptake inhibitors are superior to imipramine and alprazolam in alleviating panic attacks: a meta-analysis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995; 10:45–49.

124. Bakker A, van Balkom AJ, Spinhoven P. SSRIs vs. TCAs in the treatment of panic disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002; 106:163–167.

125. van Balkom AJ, Bakker A, Spinhoven P, Blaauw BM, Smeenk S, Ruesink B. A meta-analysis of the treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: a comparison of psychopharmacological, cognitive-behavioral, and combination treatments. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997; 185:510–516.

126. Bandelow B, Wedekind D, Leon T. Pregabalin for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a novel pharmacologic intervention. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007; 7:769–781.

127. Stein DJ, Baldwin DS, Baldinetti F, Mandel F. Efficacy of pregabalin in depressive symptoms associated with generalized anxiety disorder: a pooled analysis of 6 studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008; 18:422–430.

128. Schmitt R, Gazalle FK, Lima MS, Cunha A, Souza J, Kapczinski F. The efficacy of antidepressants for generalized anxiety disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2005; 27:18–24.

129. Stein DJ, Ipser JC, Balkom AJ. Pharmacotherapy for social phobia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004; (4):CD001206.

130. Fedoroff IC, Taylor S. Psychological and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001; 21:311–324.

131. Stein DJ, Ipser JC, Seedat S. Pharmacotherapy for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006; (1):CD002795.

132. Stein DJ, Ipser J, McAnda N. Pharmacotherapy of posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of meta-analyses and treatment guidelines. CNS Spectr. 2009; 14:1 Suppl 1. 25–31.

133. Rosa-Alcázar AI, Sánchez-Meca J, Gómez-Conesa A, Marín-Martínez F. Psychological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008; 28:1310–1325.

134. Stein DJ, Ipser JC, Baldwin DS, Bandelow B. Treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2007; 12:2 Suppl 3. 28–35.

135. Rosenstein DL, Nelson JC, Jacobs SC. Seizures associated with antidepressants: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993; 54:289–299.

136. Kanner AM. Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with developmental disorders and epilepsy: a practical approach to its diagnosis and treatment. Epilepsy Behav. 2002; 3:7–13.

137. Curran S, de Pauw K. Selecting an antidepressant for use in a patient with epilepsy. Safety considerations. Drug Saf. 1998; 18:125–133.

138. Spiller HA, Ramoska EA, Krenzelok EP, Sheen SR, Borys DJ, Villalobos D, et al. Bupropion overdose: a 3-year multi-center retrospective analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 1994; 12:43–45.

139. Markowitz JC, Brown RP. Seizures with neuroleptics and antidepressants. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1987; 9:135–141.

140. Harris CR, Gualtieri J, Stark G. Fatal bupropion overdose. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1997; 35:321–324.

141. Blumer D. Antidepressant and double antidepressant treatment for the affective disorder of epilepsy. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997; 58:3–11.

143. Ketter TA, Post RM, Theodore WH. Positive and negative psychiatric effects of antiepileptic drugs in patients with seizure disorders. Neurology. 1999; 53:5 Suppl 2. S53–S67.

144. Perucca P, Mula M. Antiepileptic drug effects on mood and behavior: molecular targets. Epilepsy Behav. 2013; 26:440–449.

145. Lee JJ, Song HS, Hwang YH, Lee HW, Suh CK, Park SP. Psychiatric symptoms and quality of life in patients with drug-refractory epilepsy receiving adjunctive levetiracetam therapy. J Clin Neurol. 2011; 7:128–136.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download