Dear Editor:

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) is a subtype of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) accounting for 18% of all PTCL. Clinical features commonly include constitutional symptoms, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, and skin eruptions1. On rare occasions, B-cell lymphomas can develop in patients with AITL, and most of the subsequent B-cell lymphomas are known to be diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), which usually occur at lymph nodes or in bone marrows. Cutaneous DLBCLs originating from AITL are even rarer 234. Here we report a patient who developed secondary cutaneous DLBCL in addition to underlying AITL.

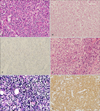

In April 2010, a 77-year-old Korean man presented with a month-long complaint of skin rash and dry cough (Fig. 1A). Biopsy of the enlarged left cervical lymph node was performed. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections showed a dense cellular infiltration. The nodal architecture was partially effaced by a polymorphous infiltrate of small to medium-sized lymphoid cells. Immunohistochemical study demonstrated that the infiltrated cells were helper T cells (positive for CD3, CD4, CD10, Bcl-6 and negative for CD20, CD56, myeloperoxidase). (Fig. 2A~C). Additionally, Southern blot analysis demonstrated a clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor-gamma gene, and no Epstein- Barr virus (EBV)-infected cells were found by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay in the bone marrow. However, an additional PCR assay using a blood sample showed 1,500 copies of EBV DNA per ml, positive for EBV infection. Based on the clinical presentation and histological findings, the patient was diagnosed with stage IV AITL. Eight months after the initial diagnosis of AITL, the patient had a solitary plaque on his right thigh (Fig. 1B). A skin biopsy revealed nodular infiltration of polymorphic cells in dermis, but this time the tumor cells were positive for CD20, PAX5, BCL-2, and EBV, but negative for CD3 and CD45RO (Fig. 2D~F). Three months after diagnosis of EBV-associated DLBCL of the skin, the patient died of respiratory failure caused by severe pneumonia.

To date, only two cases of cutaneous EBV-associated DLBCL in patients with AITL have been reported. In both reports, initial AITL was EBV-positive using special staining23. Therefore, our case is the first report of cutaneous DLBCL originating from AITL, in which the initial AITL was EBV-negative.

Cases of both subsequent and concurrent developments of DLBCL in AITL have been reported, but only limited to journals of pathology2345. Some of these cases showed absence of EBV infection in biopsy specimen of initial AITL, shedding light on some other possible etiologic factors of secondary lymphoma development2. However, despite the absence of EBV-infected B-cells in the initial biopsy specimen of our present case, EBV infection was found by PCR testing of a blood sample. This suggests the importance of testing for EBV infection even when the initial AITL biopsy specimen does not yield EBV positivity.

Our case adds clinical evidence that EBV infection could be the culprit of DLBCL development in AITL patients, and suggests that the detection of EBV infection using PCR on a blood sample can be a more sensitive tool than EBV staining of biopsy specimen.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download