Abstract

Background

Pityriasis lichenoides (PL)-like skin lesions rarely appear as a specific manifestation of mycosis fungoides (MF).

Objective

We investigated the clinicopathological features, immunophenotypes, and treatments of PL-like MF.

Methods

This study included 15 patients with PL-like lesions selected from a population of 316 patients diagnosed with MF at one institution.

Results

The patients were between 4 and 59 years of age. Four patients were older than 20 years of age. All of the patients had early-stage MF. In all patients, the atypical lymphocytic infiltrate had a perivascular distribution with epidermotropism. The CD4/CD8 ratio was <1 in 12 patients. Thirteen patients were treated with either narrowband ultraviolet B (NBUVB) or psoralen+ultraviolet A (PUVA), and all of them had complete responses.

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is a neoplasm of the immune system. It is characterized by neoplastic T lymphocytes that home to the skin, producing characteristic lesions. Initially, various erythematous patches develop. These may be chronic, existing for several years until they become plaques, nodules, erythroderma, or tumors. It is often difficult to diagnose MF in its early phase, either because of overlapping features with benign inflammatory dermatoses or because of complex and occasionally conflicting clinicopathological findings1. Clinicopathological variants of MF include hyperkeratotic-, bullous-, hypopigmented-, hyperpigmented-, porokeratotic-, granulomatous-, folliculotropic-, pustular-, verrucous-, erythrodermatous-, and pagetoid reticulosis2.

Pityriasis lichenoides (PL)-like MF is a rare subtype of MF that involves the same skin lesions as PL. Histologically, PL-like MF has the findings of MF3. In this study, we investigated the clinical, pathological, and immunohistochemical features and treatment of PL-like MF.

Fifteen patients, who had a clinical features of erythematous scaly, crusted macules, papules, or plaques (PL-like skin lesions) and histopathological features of MF according to the diagnostic criteria of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)4 were enrolled in this study. We excluded any patients who was not shown obvious histopathological features of MF. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Kosin University Gospel Hospital (IRB no. 91961-ABG-15-031).

We collected data regarding patient age, gender, disease duration, skin lesion distribution and shape, symptoms, TNM stage, and treatments. Clinical photographs were taken at every follow-up visit with the same digital camera (α350; Sony, Tokyo, Japan), in the same position, and under controlled lighting conditions. Two independent dermatologists assessed patient responses to phototherapy based on the photographs. Their evaluation defined the clinical response as complete improvement (95% or greater clinical improvement); partial improvement (50% or greater clinical improvement); or no response (<50% clinical improvement). After treatment was complete, patients were followed every one to two months to detect recurrence.

Biopsies were conducted on the PL-like lesions. Evaluation was based on the early MF findings of Pimpinelli et al.5 Typical MF and PL findings were observed. Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained using monoclonal antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD30. In order to evaluate the gene rearrangement of the T cell gamma receptor, DNA was separated from 10 paraffin-embedded tissues for polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Of the 316 MF patients, 15 (4.7%) had PL-like MF. Twelve of the 15 patients (80.0%) were male, and three (20.0%) were female. The patient ages ranged from 4 to 59 years, with a mean age of 17.2 years. Eleven patients (73.3%) were 20 years old or younger and four patients (26.7%) were older than 20 years of age. The disease duration was defined as the length of time between the disease onset and the first hospital visit. It ranged from one month to five years, with a mean disease duration of 1.5 years. Ten of the 15 patients (66.7%) experienced itching, but the remaining five had no subjective symptoms. Two patients had diffuse PL-like lesions all over the body, including the face. Twelve had lesions on the trunk and extremities, and one had lesions only on his extremities. All patients had erythematous or brownish papules. According to the TNM classification, 14 (93.3%) patients had Stage IB, and one (6.7%) had Stage IA disease. None of the patients had lymph node or visceral organ involvement.

The histological features of both MF and PL were observed in all 15 cases. Epidermotropism, "haloed" lymphocytes and atypical cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, were observed in all 15 cases (100%). Lymphocytes were found along the basal layer of the epidermis in 14 cases (93.3%). Intraepidermal lymphocytes, which are larger than dermal lymphocytes, were identified in 13 cases (86.7%). Parakeratosis was identified in 11 cases (73.3%). Finally, six cases had Pautrier's microabscesses (40.0%). There were also various histopathological findings in the dermis. Stuffed lymphocytes were observed in the dermal papillae in 14 cases (93.3%). Coarse collagen bundles were found in the papillary dermis in 13 cases (86.7%). Eleven cases (73.3%) had a psoriasiform lichenoid pattern. Perivascular cell infiltration was observed in all of the patients. In addition, erythrocyte extravasation, basal vacuolar change, and necrotic keratinocytes were identified in 14 (93.3%), 13 (86.7%), and 7 (46.7%) patients, respectively.

In most cases, the atypical lymphocytes expressed the CD3 antigen. In 12 cases (80.0%), CD8-positive T cells were more frequently observed than CD4-positive T cells. Two (patient 7, 10) of these 12 cases showed predominance of CD8-positive T cells in the dermis compared to CD4-positive T cells, and predominance of CD4-positive T cells in the epidermis compared to CD8-positive T cells. Thirteen patients had CD30-negativity of the lesion. PCR was used for T cell receptor γ gene rearrangement in 10 patients. Monoclonal findings were confirmed in eight patients (80.0%).

Narrowband ultraviolet B (NBUVB) and psoralen+ultraviolet B (PUVA) therapy was performed in 10 and 3 patients, respectively. All patients who received PUVA therapy showed complete improvement. Among them, one patient (patient 2) developed classic MF 10 years later and then had full improvement after NBUVB therapy. All patients treated with NBUVB also experienced full improvement. The follow-up period after diagnosis ranged from five months to 12 years, with a mean of 2.9 years. Among patients for whom follow up data were available, at the final follow up, eight of 10 patients (80.0%) in the NBUVB group remained relapse-free. None of the patients died from PL-like MF.

MF is classified according to its natural course and prognosis into early (stage IA, IB, and IIA) and advanced (stage IIB, III, and IV) stages. Early MF presents with a variety of patches and plaques without internal involvement, but may progress to a more advanced stage1. Variant forms of MF, whose clinical and histological patterns differ from those of typical MF, have been reported2. It is important to understand the characteristics of these variant forms. PL-like MF, first reported by Ko et al.3, is an MF subtype that is poorly understood. There are few prior studies addressing PL-like MF.

All of the patients in our study were diagnosed with early MF. Those with PL-like MF are expected to have better prognoses than those with other variants including bullous, granulomatous, and folliculotropic forms.

It is crucial that PL-like lesions are differentiated from those of PL, papular MF, and lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) using histology. de Unamuno Bustos et al.6 reported that PL, PL-like MF, papular MF, and LyP all produce papular lesions with histological MF patterns (Table 4). PL and PL-like MF have been described as having similar clinical and histological findings. Three of four patients were initially diagnosed with PL based on their clinical and histological associations; however, additional histological tests confirmed that they had PL-like MF6. The important clinical differentiation between PL and PL-like MF is that PL spontaneously heals within several months. PL-like MF demonstrates histological features of both MF (Pautrier's microabscess, lymphocytes aligned along basal cells, intraepidermal lymphocytes larger than dermal lymphocytes, haloed lymphocytes, stuffed lymphocytes in the dermal papilla, coarse collagen bundles in the papillary dermis) and PL (necrotic keratinocytes, spongiosis, erythrocyte extravasation, and exocytosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils)3. In papular MF, there are symmetrically distributed chronic papular skin lesions on the trunk and extremities. However, it does not include PL findings, such as erythrocyte extravasation or necrotic keratinocytes and immunohistochemical staining reveals that CD4-positive T cells usually predominate compared to CD8-positive T cells. LyP is a histologically malignant but indolent cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by a benign course of chronic, recurrent, or disappearing papular lesions. There are five histological types (A, B, C, D, and E) of LyP. Type B is similar to MF and involves atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromatic cerebriform nuclei on histology. Papular MF was recently suggested to be a subtype of LyP7. Alternatively, papular MF and LyP may actually be the same disease. LyP and PL often have similar clinicopathological findings. Therefore, the distinction between LyP and PL, especially pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA), can be particularly difficult. In the proper clinical setting, the presence of large atypical CD30+ cells favors the diagnosis of LyP68.

The malignant potential of PL is debated. There are some reports of "atypical PLEVA" with transformation to MF89. Rivers et al.10 reported that of 13 patients initially diagnosed with PL, six were ultimately diagnosed with MF. It is likely that these cases can be explained by misdiagnosis(of PL-like MF as PL) rather than clinical progressions from PL to MF, considering what is known about the general clinical course of the disease. It may be that cases that involved a change in diagnosis to MF actually had MF from the beginning. Great attention should be paid to the possibility of true clinicopathologic MF variants in cases of atypical forms of PL. Regular follow-up is necessary based on the clinical course and histological findings8.

Dereure et al.11 found that 65% of 20 PLEVA patients had T cell clones. Massone et al.12 found that 50%~60% of MF patients had T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangements. This suggests that TCR is not a very useful method of differentially diagnosing PL and PL-like MF. In this study, 10 patients underwent the tests, and 80% of PL-like MF cases were verified to exhibit monoclonality.

MF treatments are determined based on the presence of systemic conditions, age, and disease course. Skin-directed therapies, including phototherapy (PUVA, NBUVB) and topical chemotherapeutic agents (mechlorethamine, nitrogen mustard, carmustine), are known to be effective, safe, and convenient, particularly in early MF8. Also, UVA1 has a sensitive effect on neoplastic cells by increasing production of tumor necrosis factor-α, and it might be an effective treatment for MF13.

Ozawa et al.14 found that NBUVB induces T cell apoptosis in inflammatory skin lesions and expresses cell toxicity. Based on this mechanism, NBUVB has been used to treat various inflammatory skin diseases, including psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and lichen planus, which all involve T cell infiltration into the epidermis and dermis. NBUVB was also reported to inhibit T cell neoplastic proliferation and penetration into the upper dermis and effectively treated MF in Asian populations1516. Therefore, NBUVB can also be used for PL-like MF, which develops mostly in the early stage of MF and demonstrates neoplastic T cell infiltration into the epidermis and the upper dermis.

PUVA is therapeutic because it induces tumor cell apoptosis and DNA damage, suppresses keratinocyte cytokine production, and depletes Langerhans cells17. It has been widely used as an effective first-line treatment of early MF and as a supplementary treatment for advanced MF18.

There are only a few studies that have addressed PL-like MF phototherapy. Most of these studies involved combination therapy; therefore, the effects of phototherapy alone are not fully understood. Wang et al.19 reported one case of complete response using topical corticosteroids. de Unamuno Bustos et al.6 reported three cases of combination therapy that included PUVA and one case of PUVA therapy alone. They found that there was a partial response in the three cases of combination therapy, and a complete response in the PUVA-only case. One of the authors of this study reported cases of successful treatment of PL-like MF using PUVA3. Including previous study data, three PUVA therapy patients and 10 NBUVB therapy patients demonstrated full improvement in this study. These findings suggest that phototherapy is sufficient for the treatment of PL-like MF. The mean follow-up period after diagnosis was 2.9 years. There have been cases of recurrence in one PUVA case and two NBUVB cases. According to long term follow-up data of this study, patients had favorable prognoses similar to other reports3619. PL-like MF is a rare type of early MF that mainly develops in young patients and some adult patients and has a favorable prognosis. Its presentation is similar to that of PL. de Unamuno Bustos et al.6 also reported four adult PL-like MF patients. Also, there is high possibility of misdiagnosis, so there could be more cases than reported. Therefore, a clear understanding of the diagnosis and follow-up are needed. Histological findings of both MF and PL are present in PL-like MF. Based on immunohistochemistry, there are more CD8-positive cells than CD4-positive cells in PL-like MF, characterized by a CD8+ cytotoxic phenotype, similar to the findings in PLEVA.

This study involved Asian patients, who have not been studied extensively in this field. We observed that the disease occurred in adults and that NBUVB can be used for PL-like MF due to its inhibition of T cell neoplastic proliferation and penetration into the upper dermis16. We also observed the favorable prognosis of this variant of MF by analyzing long-term follow-up data. PL-like MF lesions are easily misdiagnosed or confused with other papular skin diseases. Therefore, skin biopsy is required for accurate diagnosis.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) Generalized erythematous scaly discrete papules on the whole body (patient 1). (B) Brownish to erythematous crustered scaly papules (patient 6).

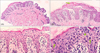

Fig. 2

(A) Biopsy specimens showing psoriasiform lichenoid infiltration (H&E, ×40). (B) Upper epidermal necrosis (arrow) and dermal papillae stuffed with lymphocytes (H&E, ×100). (C) Epidermotropism, "haloed" lymphocytes, and basal vacuolar change (H&E, ×200). (D) Intraepidermal lymphocytes that are larger than those in the dermis, hyperchromatic atypical cells (arrows), and Pautrier's microabscess (arrowhead) (H&E, ×400).

Fig. 3

Some atypical lymphocytes with positive immunohistochemical staining of (A) CD3, (B) CD4, (C) CD8, and negative staining of (D) CD30. CD8-positive T cells are predominant than CD4-positive T cells in the dermis, and CD4-positive T cells are predominant than CD8-positive T cells in the epidermis (×100) (patient 7).

Table 1

Clinical data, treatment, outcomes, and follow-up of patients with PL-like MF

Table 2

The histopathologic findings of patients with PL-like MF

Table 3

Immunohistochemical and genotypic findings in patients with PL-like MF

Table 4

Differentiation of PL, PL-like MF, papular MF and type B lymphomatoid papulosis

References

1. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, Moskowitz A, Querfeld C. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. Diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70:205.e1–205.e16.

2. Ahn CS, ALSayyah A, Sangüeza OP. Mycosis fungoides: an updated review of clinicopathologic variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014; 36:933–948.

3. Ko JW, Seong JY, Suh KS, Kim ST. Pityriasis lichenoides-like mycosis fungoides in children. Br J Dermatol. 2000; 142:347–352.

4. Olsen E, Vonderheid E, Pimpinelli N, Willemze R, Kim Y, Knobler R, et al. Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007; 110:1713–1722.

5. Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, Vonderheid E, Haeffner AC, Stevens S, et al. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005; 53:1053–1063.

6. de Unamuno Bustos B, Ferriols AP, Sánchez RB, Rabasco AG, Vela CG, Piris MA, et al. Adult pityriasis lichenoides-like mycosis fungoides: a clinical variant of mycosis fungoides. Int J Dermatol. 2014; 53:1331–1338.

7. Vonderheid EC, Kadin ME. Papular mycosis fungoides: a variant of mycosis fungoides or lymphomatoid papulosis? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006; 55:177–180.

8. Cerroni L. Skin lymphoma: the illustrated guide. 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell;2014.

9. Magro C, Crowson AN, Kovatich A, Burns F. Pityriasis lichenoides: a clonal T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Hum Pathol. 2002; 33:788–795.

10. Rivers JK, Samman PD, Spittle MF, Smith NP. Pityriasis lichenoides-like lesions associated with poikiloderma: a precursor of mycosis fungoides. Br J Dermatol. 1986; 115:17.

11. Dereure O, Levi E, Kadin ME. T-Cell clonality in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a heteroduplex analysis of 20 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000; 136:1483–1486.

12. Massone C, Kodama K, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Histopathologic features of early (patch) lesions of mycosis fungoides: a morphologic study on 745 biopsy specimens from 427 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005; 29:550–560.

13. Suh KS, Kang JS, Baek JW, Kim TK, Lee JW, Jeon YS, et al. Efficacy of ultraviolet A1 phototherapy in recalcitrant skin diseases. Ann Dermatol. 2010; 22:1–8.

14. Ozawa M, Ferenczi K, Kikuchi T, Cardinale I, Austin LM, Coven TR, et al. 312-nanometer ultraviolet B light (narrow-band UVB) induces apoptosis of T cells within psoriatic lesions. J Exp Med. 1999; 189:711–718.

15. Jang MS, Baek JW, Park JB, Kang DY, Kang JS, Suh KS, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy of early stage mycosis fungoides in Korean patients. Ann Dermatol. 2011; 23:474–480.

16. Krutmann J, Morita A. Mechanisms of ultraviolet (UV) B and UVA phototherapy. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999; 4:70–72.

17. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, Moskowitz A, Querfeld C. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. Prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70:223.e1–223.e17.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download