Abstract

Even though atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases, its treatment remains a challenge in clinical practice, with most approaches limited to symptomatic, unspecific anti-inflammatory, or immunosuppressive treatments. Many studies have shown AD to have multiple causes that activate complex immunological and inflammatory pathways. However, aeroallergens, and especially the house dust mite (HDM), play a relevant role in the elicitation or exacerbation of eczematous lesions in many AD patients. Accordingly, allergen-specific immunotherapy has been used in AD patients with the aim of redirecting inappropriate immune responses. Here, we report three cases of refractory AD sensitized to HDM who were treated with sublingual immunotherapy.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) remains a challenging condition in clinical practice, and the responsible pathogenic mechanisms are diverse. However, convincing evidence indicates that in some patients aeroallergens, especially the house dust mite (HDM), play a relevant role in exacerbating eczematous skin lesions and that the disease is associated with increased serum immunoglobulin (Ig) E levels in the majority of AD patients1. Accordingly, allergen-specific immunotherapy (SIT) has been used in AD patients with the aim of redirecting inappropriate immune responses2.

The ability of SIT based on a subcutaneous HDM preparation to improve eczema in AD patients was recently investigated in a randomized double-blind trial and an uncontrolled pilot study3,4. Owing to its efficacy and noninvasive nature, sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) has raised considerable interest5,6.

Here, we report three patients with refractory AD and hypersensitivity to HDM who were treated with a combination of SLIT and conventional therapy to varying degrees of success.

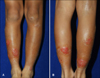

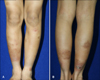

The first patient was an 11-year-old boy who presented with severe vesicular eczematous nodules and plaques on the fingers and intense pruritus of several years' duration on his forearms and lower legs (Fig. 1). He had a history of persistent rhinitis, but no familial atopic history. Laboratory tests showed total IgE levels of 40.3 kU/L (0~100 kU/L) and a mildly elevated eosinophil count. Multiple allergosorbent chemiluminescent assay (MAST-CLA) testing (AdvanSure AlloScreen; LG Life Sciences, Daejeon, Korea) indicated sensitization only to HDM: Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, +3 and Dermatophagoides farinae, +3. His clinical AD severity score (SCORAD) at first visit was 56. Despite receiving over 3 months of treatment with current standard medical therapies such as topical moisturizer, topical steroid (0.25% prednicarbate cream and 0.1% methylprednisolone aceponate cream), and oral antihistamine (0.5 mg·kg-1·day-1 of ketotifen and 0.2 mg·kg-1·day-1 of levocetirizine), his lesions showed only partial response. We then started specific SLIT with Staloral 10 (standardized D. pteronyssinus extract 10 IR/ml) and Staloral 300 (standardized D. farinae extract 300 IR/ml) (Stallergenes, Paris, France). Treatment was administered according to a plan, which consisted of a build-up phase and maintenance phase (Fig. 2). The plan was strictly adhered to during the build-up phase, but the patient was allowed to adjust the doses from 2 to 4 drops according to his condition during the maintenance phase. He also received sustained treatment with a topical steroid and oral antihistamines. The total duration of SLIT was more than 12 months, and the only side effects experienced were transient nausea, abdominal pain, and aggravation of rhinitis. At 6 months after the start of treatment, significant clinical improvement of his dermatitis was observed (SCORAD 15), with a further mild improvement after 12 months (SCORAD 12). His skin lesions, which proved refractory to conventional therapy, had considerably improved for the better and he continues SLIT with excellent tolerance (Fig. 3).

The second patient was a 23-year-old man with an 8-year history of generalized lichenoid patches and a severe itching sensation occurring on the entire body, but especially on the neck and extremities. He was treated with current standard medical therapies for 7 years. Laboratory tests revealed a serum specific IgE (ImmunoCAP Complete Allergens; Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden) level of 53 kU/L to D. pteronyssinus and 70 kU/L to D. farinae. We regarded him as a refractory AD patient and decided to initiate SLIT using the same schedule described for case 1 (Fig. 2). His baseline SCORAD score was 19. SLIT was administered for more than 12 months, and the only specific side effect was allergic rhinitis. At one time during the treatment period, the patient stopped SLIT for 2 weeks due to the transient exacerbation of rhinitis. Although SLIT did not significantly reduce his SCORAD score, which was 22 at 6 months and 17 at 12 months, the patient was satisfied with the results of SLIT and continued treatment because his subjective symptoms and oral medication dosages significantly decreased. More specifically, the cumulative dose and duration of cyclosporine decreased from 6,325 mg and 178 days for the first 6 months to 4,275 mg and 131 days for the second 6-month period.

The third patient was a 23-year-old man who presented with a history of AD from infancy and allergic rhinitis of 10 years' duration. The condition had not been effectively controlled with current standard medical therapies for several years. His skin lesions were oozing, itchy erythematous patches on the face and excoriated patches on the trunk and extremities. Laboratory tests showed a total IgE level of 1,873 kU/L, a specific IgE of 17.3 kU/L to D. pteronyssinus, and a specific IgE of 17.1 kU/L to D. farinae. The Mast-CLA test revealed sensitivities of +4 to both D. pteronyssinus and D. farinae. He was considered a refractory AD patient and was started on SLIT using the same treatment schedule used in the previous cases (Fig. 2). His baseline SCORAD value 34, and he achieved a mild clinical improvement of dermatitis after 6 months of therapy (SCORAD: 19). During SLIT treatment, the only side effect he experienced was transient abdominal discomfort. However, after 12 months of treatment, the patient showed aggravation in terms of SCORAD score (SCORAD: 33) and quality of life. These disappointing outcomes were reflected by increases in the cumulative dose and duration of cyclosporine (from 875 mg and 35 days for the first 6 months to 2,100 mg and 63 days for the second 6 months). Furthermore, short-term low-dose oral corticosteroids (8 mg/day of methylprednisolone) were not required for the treatment of acute exacerbations in the first 6-month period, but were administered during the second 6-month period (total duration: 17 days, cumulative dose: 80 mg). During the treatment period, the patient's rhinitis improved but his eczematous lesions waxed and waned.

AD is highly heterogeneous and different factors act as triggers in individual patients. Accordingly, it has become more important for subgroups of AD patients to be carefully classified to ensure optimal treatment. Total serum IgE levels, serum specific IgE antibody tests to HDM, and the MAST-CLA test may be useful for classifying patients in terms of the extrinsic forms of AD7.

Recent studies have shown that in AD patients with a positive allergic test, subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) based on HDM allergen extracts is effective at reducing SCORAD scores, mean treatment time, and the need for topical corticosteroids3,4. Furthermore, it is now widely accepted that SLIT is much safer than SCIT. In particular, no evidence of anaphylactic shock has been recorded after the administration of more than 500 million doses to humans8,9. SLIT provided a significant improvement in two open controlled studies10,11. Moreover, one randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study demonstrated its clinical effectiveness in children with mild to moderate allergic AD12. The sublingual area, in which antigen-presenting cells are abundant, has been shown to be a convenient location for allergen administration and for the induction of mucosal tolerance. As a result, SLIT is accepted as an effective therapeutic strategy for the modulation of an ongoing immunopathological response in patients with allergic disorders13,14. We therefore attempted to use SLIT for the treatment of refractory AD patients, defined as patients who had not been effectively controlled by current standard medical therapies including topical moisturizers, topical corticosteroids, and oral antihistamines for more than 3 months.

Some studies have shown that patients with mild-moderate AD show obvious improvements in symptoms, visual analog scale scores, and SCORAD scores after SLIT. On the other hand, in patients with severe AD, minimal benefits of SLIT have been reported12,15. Among our three cases, the first had the most severe AD, but clinical outcomes after SLIT such as the SCORAD index and subjective symptoms were substantially better in this case than in the other 2 cases. However, although the second case achieved a slight clinical response, the accumulated dose and duration of his oral medication (cyclosporine) were significantly reduced during the second 6 months of the 12-month treatment period, and no aggravation of AD occurred. Meanwhile, the third case achieved a disappointing clinical outcome. The total IgE level in this patient was higher than that of the other patients, and we can consider the possibility that other allergens besides HDM triggered and aggravated his AD. In addition, although although there is no consensus on treatment duration, a longer duration of therapy is needed to achieve properly defined outcomes. Nevertheless, we want to emphasize that all three cases underwent prolonged and unsuccessful conventional therapy. From the perspective of safety, all three cases achieved positive results, with no severe side effects requiring treatment termination.

Though our three cases showed varying clinical responses to SLIT, we believe SLIT can be an alternative, safe treatment option for allergic AD refractory to long-term conventional treatment.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Severe vesicular eczematous nodules and plaques on lower legs in the patients with refractory atopic dermatitis (case 1) at baseline.

Fig. 2

Sublingual immunotherapy consists of a build up phase and maintenance phase. IR is biological unit, and a concentration of 100 IR defined by the capacity of the allergen to elicit by skin prick test a geometric mean wheal size of 7 mm diameter in 30 patients sensitive to the corresponding allergen.

References

1. Scalabrin DM, Bavbek S, Perzanowski MS, Wilson BB, Platts-Mills TA, Wheatley LM. Use of specific IgE in assessing the relevance of fungal and dust mite allergens to atopic dermatitis: a comparison with asthmatic and nonasthmatic control subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999; 104:1273–1279.

2. Moingeon P, Batard T, Fadel R, Frati F, Sieber J, Van Overtvelt L. Immune mechanisms of allergen-specific sublingual immunotherapy. Allergy. 2006; 61:151–165.

3. Werfel T, Breuer K, Ruáff F, Przybilla B, Worm M, Grewe M, et al. Usefulness of specific immunotherapy in patients with atopic dermatitis and allergic sensitization to house dust mites: a multi-centre, randomized, dose-response study. Allergy. 2006; 61:202–205.

4. Nahm DH, Kim ME. Treatment of severe atopic dermatitis with a combination of subcutaneous allergen immunotherapy and cyclosporin. Yonsei Med J. 2012; 53:158–163.

5. Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N. Aria Workshop Group. World Health Organization. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001; 108:5 Suppl. S147–S334.

7. Novak N, Simon D. Atopic dermatitis - from new pathophysiologic insights to individualized therapy. Allergy. 2011; 66:830–839.

8. Agostinis F, Tellarini L, Canonica GW, Falagiani P, Passalacqua G. Safety of sublingual immunotherapy with a monomeric allergoid in very young children. Allergy. 2005; 60:133.

9. Grosclaude M, Bouillot P, Alt R, Leynadier F, Scheinmann P, Rufin P, et al. Safety of various dosage regimens during induction of sublingual immunotherapy. A preliminary study. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002; 129:248–253.

10. Mastrandrea F, Serio G, Minelli M, Minardi A, Scarcia G, Coradduzza G, et al. Specific sublingual immunotherapy in atopic dermatitis. Results of a 6-year follow-up of 35 consecutive patients. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2000; 28:54–62.

11. Petrova SIu, Berzhets VM, Al'banova VI, Bystritskaia TF, Petrova NS. Immunotherapy in the complex treatment of patients with atopic dermatitis with sensitization to house dust mites. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 2001; (1):33–36.

12. Pajno GB, Caminiti L, Vita D, Barberio G, Salzano G, Lombardo F, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy in mitesensitized children with atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007; 120:164–170.

13. Akdis CA, Barlan IB, Bahceciler N, Akdis M. Immunological mechanisms of sublingual immunotherapy. Allergy. 2006; 61:Suppl 81. 11–14.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download