Abstract

Background

The necessity of performing antifungal susceptibility tests is recently increasing because of frequent cases of oral candidiasis caused by antifungal-resistant Candida species. The Etest (BioMerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) is a rapid and easy-to-perform in vitro antifungal susceptibility test.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to determine the minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of antifungal agents by using the Etest for Candida species isolated from patients with oral candidiasis.

Methods

Forty-seven clinical isolates of Candida species (39 isolates of Candida albicans, 5 isolates of C. glabrata, and 3 isolates of C. tropicalis) were tested along with a reference strain (C. albicans ATCC 90028). The MIC end points of the Etest for fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, and amphotericin B susceptibility were read after the 24-hour incubation of each isolate on RPMI 1640 agar.

Results

All Candida isolates were found susceptible to voriconazole and amphotericin B. However, all five isolates of C. glabrata were resistant to itraconazole, among which two isolates were also resistant to fluconazole.

Conclusion

This study revealed that the Etest represented a simple and efficacious method for antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida species isolated from oral candidiasis patients. Therefore, voriconazole and amphotericin B should be recommended as effective alternatives for the treatment of oral candidiasis.

Candida species, which are part of the normal flora in the oral cavity, may cause opportunistic infections under various circumstances that compromise host immunity. Oral candidiasis is recently increasing due to old age, denture use, diabetes, systemic steroid and antibiotic use, pernicious anemia, malignancy, radiation therapy on the head and neck, and cell-mediated immunodeficiency12. With the increasing use of antifungal agents, several reports on antifungal resistance have been published3456789101112131415. Therefore, antifungal susceptibility testing becomes necessary for the effective treatment of oral candidiasis.

The Etest (BioMerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) is a recently commercialized antimicrobial susceptibility test. A long plastic strip consisting of a predefined concentration gradient of an antifungal is placed on an inoculated agar plate. After incubation for the diffusion of the antifungal, the oval-shaped inhibition zone of candidal growth may indicate the minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs). Thus, the Etest is simple, rapid, and easy to use. Moreover, the results of the Etest are consistent with those of a reference method, the broth microdilution procedure161718. As a basis for the treatment of infection caused by oral Candida species, the MICs of fluconazole (FCZ), itraconazole (ICZ), voriconazole (VCZ), and amphotericin B (AMB) for Candida isolates from patients with oral candidiasis were determined by performing Etest on RPMI 1640 agar.

Among the patients who visited the Department of Dermatology of Dongguk University Gyeongju Hospital for a year (September 2013 to August 2014), those suspected of having oral candidiasis were subjected to a potassium hydroxide test of skin lesions in which hyphae were observed along with conidia. Oral candidiasis was finally diagnosed with fungal culture in 45 patients. Fortyseven isolates of Candida species (39 of C. albicans, 5 of C. glabrata, and 3 of C. tropicalis) were obtained, and two cases of C. albicans co-infection with either C. glabrata or C. tropicalis were observed (Table 1). These isolates were tested for susceptibility against FCZ, ICZ, VCZ, and AMB. Oral Candida species were identified according to colony morphology, microscopic features, germ tube test, and API 20C kit test (BioMerieux). Candida albicans ATCC 90028 was used as the reference strain.

Sabouraud's dextrose agar (SDA) was used for the subculture of fungal isolates. For the antifungal susceptibility testing with Etest, RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 8.4 g L-glutamine, 34.5 g morpholinepropanesulfonic acid, 20 g glucose, and 17 g Bacto agar (Becton Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD, USA) were dissolved in 1 L distilled water, adjusted to pH 7.0, autoclaved at 121℃ for 15 minutes, and poured into 150 mm Petri dishes with 4.0±0.5 mm depth.

Candida isolates from oral candidiasis patients were inoculated on SDA along with the reference strain, and incubated at 35℃ in moist condition for 3 to 4 days. Yeast colonies (>1 mm diameter) on SDA were suspended in 0.85% sterile saline solution to adjust to a turbidity of a 0.5 McFarland standard. A sterile cotton swab was used to spread 500 µl fungal suspension evenly on a 150-mm RPMI plate in three directions. Etest strips were placed on plates that had been dried for 15 minutes at room temperature. The strip end with a lower concentration of the antifungal was positioned first. Etest strips of FCZ (0.016~256 µg/ml), ICZ (0.002~32 µg/ml), VCZ (0.002~32 µg/ml), and AMB (0.002~32 µg/ml) were placed perpendicular to each other on an RPMI plate. The MIC of each drug was determined after incubation for 24 and 48 hours at 35℃ in moist condition.

The MICs of the antifungals were read after incubation for 24 and 48 hours, from the scale where the growth inhibition ellipse edge intersected the strip. If the end point of growth inhibition is clear, the scale was read. The MICs of azoles, however, were difficult to read because of trailing, which is a reduced but persistent growth of Candida sp. even at high concentration of azoles, and thus determined at the concentration where the colony size was apparently reduced (Fig. 1). As the trailing effects of azoles become aggravated and the MIC of AMB markedly increases after 48 hours of incubation, Etest reading was done to determine the MICs after 24 hours. The final MIC values were based on the consensus between two readers. For quality control, the reference strain was tested simultaneously with the Candida isolates. Guidelines for the in vitro susceptibility of Candida species were adapted from the M27-A3 document from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). For FCZ, the MIC for susceptibility was ≤8 µg/ml, that for susceptible-dose dependence was 16 to 32 µg/ml, and that for resistance was ≥ 64 µg/ml. For ICZ, the MIC for susceptibility was ≤0.125 µg/ml, that for susceptible-dose dependence was 0.25 to 0.5 µg/ml, and that for resistance was ≥1 µg/ml. For VCZ, the MIC for susceptibility was ≤1 µg/ml, that for susceptible-dose dependence was 2 µg/ml, and that for resistance was ≥4 µg/ml. As interpretative criteria for AMB have not been defined in the CLSI guidelines, the MIC for susceptibility to AMB was ≤1 µg/ml, whereas the MIC for resistance to AMB was >1 µg/ml, according to Sanitá et al.19 and Negri et al.20 (Table 2).

The MICs for the reference strain, C. albicans ATCC 90028, determined after 24-hour incubation were 0.25 µg/ml against FCZ, 0.064 to 0.094 µg/ml against ICZ, 0.008 to 0.012 µg/ml against VCZ, and 0.125 to 0.19 µg/ml against AMB. From the repeated tests, identical results were obtained within a ±1 grade range, which are acceptable according to the quality control guidelines (Table 3).

The MICs for 39 isolates of C. albicans were 0.064 to 0.75 µg/ml against FCZ, 0.002 to 0.094 µg/ml against ICZ, 0.002 to 0.016 µg/ml against VCZ, and 0.012 to 0.19 µg/ml against AMB. The MICs for the five isolates of C. glabrata were 16 to 64 µg/ml against FCZ, >32 µg/ml against ICZ, 0.38 to 1.0 µg/ml against VCZ, and 0.064 to 0.19 µg/ml against AMB. The MICs for the three isolates of C. tropicalis were 0.25 to 0.75 µg/ml against FCZ, 0.012 to 0.25 µg/ml against ICZ, 0.008 to 0.094 µg/ml against VCZ, and 0.094 to 0.25 µg/ml against AMB (Table 4).

According to CLSI M27-A3 and the guidelines by Sanitá et al.19 and Negri et al.20 (Table 2), the MICs of AMB and VCZ were <1.0 µg/ml (0.012~0.25 and 0.002~1.0 µg/ml, respectively), indicating that all isolates of Candida (39 of C. albicans, 5 of C. glabrata, and 3 of C. tropicalis) were susceptible. The MICs of FCZ were 0.064 to 64 µg/ml, indicating that the 39 isolates of C. albicans and the 3 isolates of C. tropicalis were susceptible, 3 of the 5 isolates of C. glabrata were susceptible-dose dependent, and the remaining 2 isolates of C. glabrata were resistant. The MICs of ICZ were 0.002 to 2 µg/ml, revealing that the 39 isolates of C. albicans and 2 of the 3 isolates of C. tropicalis were susceptible, 1 isolate of C. tropicalis was susceptible-dose dependent, and the 5 isolates of C. glabrata were all resistant (Table 5).

Oral candidiasis is an infection caused by oral Candida species; C. albicans has been commonly detected, whereas C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. guilliermondii, and C. krusei have been isolated less frequently2122. Recently, however, as in our study, C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. tropicalis are reported to cause oral infection, as a single species or as mixed causative agents3192324. The treatment of oral candidiasis usually involves local nystatin emulsion or clotrimazole troche in cases without any complication; however, oral administration of azoles such as FCZ or ICZ is necessary for recurrent infections or chronic cases12. As several studies have been recently reported on antifungal resistance against azoles, susceptibility tests on antifungals need to be performed3456789101112131415.

Among several antifungal susceptibility tests, including the broth microdilution, disk diffusion, and flow cytometry methods, the reference method adapted by the CLSI is the broth microdilution method, which is rather difficult to perform regularly in a laboratory because it is time consuming and tedious to perform1718. The Etest, which is a simple disk diffusion method, has been used recently because its results agree well with those from the broth microdilution method6121425262728.

Although several reports have been published worldwide on antifungal susceptibility testing through the Etest of oral Candida species34681112131419, there has been only a single report25 on using the Etest on superficial Candida isolates in the Korean dermatological literature.

Therefore, we tested Candida species isolated from oral candidiasis patients by using a new Etest method, to determine their susceptibility to azoles including FCZ, ICZ, VCZ, and a polyene, AMB. For quality control, the C. albicans ATCC 90028 reference strain was used according to Carvalhinho et al.4 and Sanitá et al.19 RPMI 1640 medium was used for the Etest361619. Incubation was done at 35℃ for 24 and 48 hours, as described in Marcos-Arias et al.3 However, a trailing effect induced by azoles occurred and the MICs of AMB increased obviously after 48 hours. Therefore, the MICs from the Etest were read after 24-hour incubation.

The oral Candida species that were isolated, identified, and tested in this study exhibited various results to the tested antifungals. The range of AMB MICs was 0.012 to 0.25 µg/ml and <1.0 µg/ml, an interpretable criterion, indicating that all 39 isolates of C. albicans, 5 isolates of C. glabrata, and 3 isolates of C. tropicalis were susceptible to AMB as reported by others481219. Similarly, the range of VCZ MICs was 0.002 to 1.0 µg/ml and ≤1.0 µg/ml, indicating that all Candida isolates were susceptible to VCZ as reported by Mareş et al.8 and Belazi et al.11. However, the range of FCZ MICs was 0.064 to 64 µg/ml, indicating that all 39 C. albicans isolates and the 3 C. tropicalis isolates were susceptible, but 3 of the 5 isolates of C. glabrata were susceptible-dose dependent and the remaining 2 isolates were resistant to FCZ, as observed similarly by others811121314. Finally, the range of ICZ MICs was from 0.002 to >32 µg/ml, indicating that all isolates of C. albicans were susceptible and an isolate of C. tropicalis was susceptible-dose dependent, but all isolates of C. glabrata were resistant to ICZ as described similarly by other reports38131419.

In summary, all Candida isolates were susceptible to AMB and VCZ, which were proven to be more effective than either FCZ or ICZ. When a patient with oral candidiasis does not respond well to other antifungals, VCZ may be recommended as AMB may cause adverse reactions such as nephrotoxicity and hypokalemia. VCZ, a new secondgeneration triazole derived from FCZ, has a wide spectrum and antifungal activities against various mycoses caused by not only Candida species but also Aspergillus, Scedosporium, and Fusarium species2930. In this study, the MICs of antifungals for oral Candida species were successfully determined by using a simple method, the Etest, with RPMI 1640 medium in the clinical laboratory. Further study with more clinical isolates needs to be done to investigate the trend of antifungal resistance among oral Candida species in Korea.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1The Etest result of a Candida albicans isolate tested against fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, and amphotericin B. |

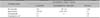

Table 2

CLSI (M27-A3) and literature guidelines for in vitro susceptibility testing of Candida species

Table 3

Quality control ranges of Candida albicans ATCC 90028, a reference strain for antifungal susceptibility test by CLSI guideline

References

1. Kundu RV, Garg A. Yeast infections: candidiasis, tinea (pityriasis) versicolor, and Malassezia (Pityrosporum) folliculitis. In : Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Loffell DJ, Wolff K, editors. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;2012. p. 2298–2307.

2. Ahn HH, Park SD, Kim KM, Park CJ, Kim HW, Kim JP, et al. Infectious skin diseases. Korean Dermatological Association. Textbook of dermatology. 6th ed. Seoul: Daehan Medical Books;2014. p. 430–437.

3. Marcos-Arias C, Eraso E, Madariaga L, Carrillo-Muñoz AJ, Quindós G. In vitro activities of new triazole antifungal agents, posaconazole and voriconazole, against oral Candida isolates from patients suffering from denture stomatitis. Mycopathologia. 2012; 173:35–46.

4. Carvalhinho S, Costa AM, Coelho AC, Martins E, Sampaio A. Susceptibilities of Candida albicans mouth isolates to antifungal agents, essentials oils and mouth rinses. Mycopathologia. 2012; 174:69–76.

5. Nweze EI, Ogbonnaya UL. Oral Candida isolates among HIV-infected subjects in Nigeria. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2011; 44:172–177.

6. Koga-Ito CY, Lyon JP, Resende MA. Comparison between E-test and CLSI broth microdilution method for antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida albicans oral isolates. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2008; 50:7–10.

7. Enwuru CA, Ogunledun A, Idika N, Enwuru NV, Ogbonna F, Aniedobe M, et al. Fluconazole resistant opportunistic oro-pharyngeal Candida and non-Candida yeast-like isolates from HIV infected patients attending ARV clinics in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2008; 8:142–148.

8. Mareş M, Mareş M, Rusu M. Antifungal susceptibility of 95 yeast strains isolated from oral mycoses in HIV-negative and HIV-positive patients. Bacteriol Virusol Parazitol Epidemiol. 2008; 53:41–42.

9. Costa CR, de Lemos JA, Passos XS, de Araújo CR, Cohen AJ, Souza LK, et al. Species distribution and antifungal susceptibility profile of oral candida isolates from HIV-infected patients in the antiretroviral therapy era. Mycopathologia. 2006; 162:45–50.

10. Bagg J, Sweeney MP, Davies AN, Jackson MS, Brailsford S. Voriconazole susceptibility of yeasts isolated from the mouths of patients with advanced cancer. J Med Microbiol. 2005; 54:959–964.

11. Belazi M, Velegraki A, Koussidou-Eremondi T, Andreadis D, Hini S, Arsenis G, et al. Oral Candida isolates in patients undergoing radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: prevalence, azole susceptibility profiles and response to antifungal treatment. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2004; 19:347–351.

12. Tapia C, González P, Pereira A, Pérez J, Noriega LM, Palavecino E. Antifungal susceptibility for Candida albicans isolated from AIDS patients with oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis: experience with Etest. Rev Med Chil. 2003; 131:515–519.

13. Davies A, Brailsford S, Broadley K, Beighton D. Resistance amongst yeasts isolated from the oral cavities of patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med. 2002; 16:527–531.

14. Silva Mdo R, Costa MR, Miranda AT, Fernandes Ode F, Costa CR, Paula CR. Evaluation of Etest and macrodilution broth method for antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida sp strains isolated from oral cavities of AIDS patients. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2002; 44:121–125.

15. Kirkpatrick WR, Revankar SG, Mcatee RK, Lopez-Ribot JL, Fothergill AW, McCarthy DI, et al. Detection of Candida dubliniensis in oropharyngeal samples from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in North America by primary CHROMagar candida screening and susceptibility testing of isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998; 36:3007–3012.

16. Lass-Flörl C, Perkhofer S, Mayr A. In vitro susceptibility testing in fungi: a global perspective on a variety of methods. Mycoses. 2010; 53:1–11.

17. Arikan S. Current status of antifungal susceptibility testing methods. Med Mycol. 2007; 45:569–587.

18. Shin JH. Antifungal drug susceptibility. Hanyang Med Rev. 2006; 26:79–85.

19. Sanitá PV, Mima EG, Pavarina AC, Jorge JH, Machado AL, Vergani CE. Susceptibility profile of a Brazilian yeast stock collection of Candida species isolated from subjects with Candida-associated denture stomatitis with or without diabetes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013; 116:562–569.

20. Negri M, Henriques M, Svidzinski TI, Paula CR, Oliveira R. Correlation between Etest, disk diffusion, and microdilution methods for antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida species from infection and colonization. J Clin Lab Anal. 2009; 23:324–330.

21. Samaranayake LP, Keung Leung W, Jin L. Oral mucosal fungal infections. Periodontol 2000. 2009; 49:39–59.

22. Lee SH, Kim SW, Bang YJ. A study on the distribution of oral candidal isolates in diabetics. Korean J Med Mycol. 2002; 7:139–148.

23. Silva S, Henriques M, Hayes A, Oliveira R, Azeredo J, Williams DW. Candida glabrata and Candida albicans co-infection of an in vitro oral epithelium. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011; 40:421–427.

24. Coco BJ, Bagg J, Cross LJ, Jose A, Cross J, Ramage G. Mixed Candida albicans and Candida glabrata populations associated with the pathogenesis of denture stomatitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2008; 23:377–383.

25. Kim YJ, Suh MK, Ha GY. Azole antifungal susceptibility testing of candida species using E test. Korean J Dermatol. 2001; 39:654–659.

26. Ranque S, Lachaud L, Gari-Toussaint M, Michel-Nguyen A, Mallié M, Gaudart J, et al. Interlaboratory reproducibility of Etest amphotericin B and caspofungin yeast susceptibility testing and comparison with the CLSI method. J Clin Microbiol. 2012; 50:2305–2309.

27. Buchta V, Vejsova M, Vale-Silva LA. Comparison of disk diffusion test and Etest for voriconazole and fluconazole susceptibility testing. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 2008; 53:153–160.

28. Morace G, Borghi E, Iatta R, Amato G, Andreoni S, Brigante G, et al. Antifungal susceptibility of invasive yeast isolates in Italy: the GISIA3 study in critically ill patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2011; 11:130.

29. Pfaller MA, Andes D, Arendrup MC, Diekema DJ, Espinel-Ingroff A, Alexander BD, et al. Clinical breakpoints for voriconazole and Candida spp. revisited: review of microbiologic, molecular, pharmacodynamic, and clinical data as they pertain to the development of species-specific interpretive criteria. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011; 70:330–343.

30. Scott LJ, Simpson D. Voriconazole: a review of its use in the management of invasive fungal infections. Drugs. 2007; 67:269–298.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download