Abstract

Background

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) have been successfully used to treat seborrheic dermatitis (SD) patients. Meanwhile, treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) with low-dose, intermittent TCI has been proved to reduce disease flare-ups. This regimen is known as a maintenance treatment.

Objective

The aim of this trial was to investigate the efficacy and tolerability of a maintenance treatment with tacrolimus ointment in patients with facial SD.

Methods

During the initial stabilization period, patients with facial SD or AD applied 0.1% tacrolimus ointment twice daily for up to 4 weeks. Clinical measurements were evaluated on either in the whole face or on separate facial regions. When an investigator global assessment score 1 was achieved, the patient applied tacrolimus twice weekly for 20 weeks. We also compared our results with recent published data of placebo controlled study to allow an estimation of the placebo effect.

Results

The time to the first relapse during phase II was similar in both groups otherwise significantly longer than the placebo group. The recurrence-free curves of two groups were not significantly different from each other; otherwise the curve of the placebo group was significantly different. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in the number of DEs, and treatment days for disease exacerbations (DEs). The adverse event profile was also similar between the 2 groups. During the 20 weeks of treatment, the study population tolerated tacrolimus ointment well.

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is characterized by erythematous scaly or greasy patches on the face, scalp, and body that usually accompany pruritus1. SD and atopic dermatitis (AD) have similar clinical symptoms, and both diseases have chronic, recurrent courses2. A typical histologic finding of SD is spongiform dermatitis with perivascular inflammatory cell infiltrates that is often indistinguishable from AD3. Additionally, it is evident that Malassezia is a factor that exacerbates both SD and AD, especially affecting the face and scalp 4567. Pharmacotherapy for relapse prevention in SD is an interesting subject for dermatological research.

The mainstays of treatment for AD and SD have been the application of topical antifungals, topical corticosteroids (TCSs), and, more recently, topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs)2891011. Maintenance approaches, by using low-dose, intermittent treatments with TCSs or TCIs for AD, have been more efficacious in preventing flares than a vehicle121314. The potency of TCSs in those studies was mostly medium to high. Long-term facial treatment with potent TCSs may not be recommendable for AD patients because of adverse effects, including telangiectasia, atrophy, and perioral dermatitis15. Moreover, steroid-phobia toward TCSs leads to frequent disease flares151617. For this reason, maintenance treatment with TCIs might be more appropriate for patients with facial eczema1819. Tacrolimus is a TCI that inhibits calcineurin, thus preventing both T-lymphocyte signal transduction and transcription of inflammatory cytokines220. Regular application of TCIs for SD has been shown to improve clinical symptoms within 2 weeks, and most patients tolerate the treatment well217212223. However, there have been few reports on the use of maintenance therapy for SD.

In this study, maintenance treatment with topical TCI for SD was compared with that for AD because the regimen with topical TCI for AD is relatively well established in other studies121314.

The aim of this study is to compare the efficacy and safety of the maintenance, twice-weekly application of tacrolimus ointment between patients with moderate to severe facial SD and those with facial AD.

In this open-label, prospective, multicenter, comparative study, male or female patients aged ≥2 years with a facial eczematous disease were recruited. Among them, patients with AD (diagnosed according to the criteria of Hanifin and Rajka) or SD (diagnosed by two professional dermatologists) that was rated at least moderate (≥3) on the investigator global assessment (IGA) scale were eligible for the stabilization phase of the study (phase I). The IGA uses a standard six-point scale of SD or AD severity (0=clear, 1=almost clear, 2=mild, 3=moderate, 4=severe, and 5=very severe). The exclusion criteria were any skin disorders other than AD in the area or areas to be treated, clinically infected skin diseases (bacteria, fungus, and virus), and extensive scarring or pigmented lesions in the area or areas to be treated.

During the study, the patients were prohibited from receiving ultraviolet therapy, nonsteroidal immunosuppressive agents, other TCS or TCI products, systemic corticosteroids, and other investigational drugs. The washout period for these therapies ranged from a minimum of 1 week (for TCSs and TCIs) to a maximum of 6 weeks (for ultraviolet treatments). The washout period for systemic nonsteroidal immunosuppressant and systemic corticosteroids used to treat AD was 2 weeks. None of the above-listed medications were permitted during the study (phases I and II), except as a study medication. Topical nonmedicated moisturizers were permitted throughout the study as long as they were applied at least 2 h before or 2 h after the application of tacrolimus ointment. Sunscreens and makeup were permitted but were not to be applied immediately before or 30 min after the application of any study treatments. The dose of systemic antihistamines was decreased or discontinued but not increased. Systemic antibiotics were allowed for the treatment of infections, as needed. In addition, the patients were allowed to use bath oils and nonmedicated emollients 2 h before and after the application of any study ointments.

This was a 20-week, prospective, multicenter, comparative study conducted at nine centers in Korea. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles described in the Declaration of Helsinki. Adult and pediatric patients with facial SD or AD who were clear of disease after up to 4 weeks of treatment with tacrolimus ointment (a stabilization phase, phase I) entered the maintenance phase (phase II) of twice-weekly treatment with tacrolimus ointment (0.1%) for 20 weeks (Fig. 1). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each hospital, and all patients (or legal caretakers) gave written informed consent before enrollment. All study treatments were applied to the active or previously involved areas of AD (IRB No. 2012-12-83, Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital).

During phase I, patients with facial SD or AD applied 0.1% tacrolimus ointment (Protopic; Astellas Pharma Korea Inc., Seoul, Korea) to the entire affected facial areas twice daily for a minimum of 7 days and a maximum of 4 weeks. At any time after 7 days, patients with an IGA score of 0 or 1 (clear or almost clear) were eligible to enter phase II. If neither of these scores were achieved by 4 weeks, the patients were excluded from the study.

During phase II, 0.1% tacrolimus ointment was applied twice weekly for 20 weeks to facial areas previously affected by SD or AD. Patients with disease relapse (defined as an IGA score of >2) were excluded from the study.

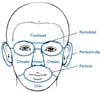

Patient assessment was conducted at baseline/day 1; weeks 1, 2, and 4/end of phase I; and at weeks 4, 8, 16, and 20/final visit of phase II. At the baseline visit, the investigator confirmed the diagnosis of SD or AD, and then identified and evaluated all areas to be treated. Clinical measurements were done on separate facial regions (forehead, periorbital, nose, chin, cheek, and perioral/periauricular regions; Fig. 2) and on the whole face (the average severity of each region). The presence of disease on each facial part, the visual analogue score (VAS) for itching, and the IGA score were determined, and all adverse events were recorded at all visits during phases I and II. As this study was a comparative study of two different diseases, the IGA instead of both the eczema area and severity index and seborrhea area and severity index was chosen for the evaluation of the severity of facial AD and SD to ensure consistency. Also, for estimating the placebo effect, the results were compared with those of the placebo group of a recent study of proactive treatment with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment twice weekly in Korea24. Raw data were obtained from the authors of the paper24.

The primary endpoint was the time to the first disease exacerbation (DE) during phase I that required a substantial therapeutic intervention, which was defined as the use of 0.1% tacrolimus ointment for >7 days to treat an area with an IGA score of 3~5 as measured on day 1 of the DE treatment period. If a patient had two DEs within <7 days (with or without any type of treatment), the episodes were combined and considered as 1 DE. The secondary study endpoints included the total number of DEs during phase II that required a substantial therapeutic intervention and treatment days for DE. Clinical improvement was assessed by using the IGA score and VAS. Safety assessment during the study included the monitoring of adverse events. An adverse event was defined as any untoward occurrence in a patient, regardless of whether it was related to the study treatment, reported by the patient, or observed by the physician.

The demographic differences between the two treatment groups were analyzed by using Fisher's exact test and the χ2 test for categorical data, and analysis of variance for continuous data. The Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were used to obtain and compare the corresponding 95% confidence intervals for the time to first disease relapse, and to estimate the median time to first disease relapse in those who experienced at least one relapse. The two treatment groups were compared by using the Wilcoxon rank sum test stratified according to disease severity and patient age. The differences between the treatment groups were analyzed by using Student's t-test for the treatment days for DE episodes and the mean IGA score for relapse episodes. The differences between the treatment groups were analyzed by using the χ2 test and one-way ANOVA in the number of disease relapse episodes and the IGA score for the first relapse, and the Mantel-Henzel test for their trend. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

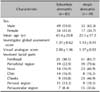

A total of 123 SD patients and 75 AD patients were enrolled in phase I of the study. The mean age was significantly different between the two groups (43.13±18.80 years for the SD group vs. 23.15±18.21 years for the AD group). Other characteristics, such as sex ratio and disease severity as assessed with IGA, were similar in the two groups.

At the completion of phase I, 83 of the 123 (67.5%) SD patients and 49 of the 75 (65.3%) AD patients showed an IGA score of <2 ("clear" and "almost clear") and completed phase I. The remaining 40 and 26 patients were excluded. The primary reason for exclusion at the completion of phase I was an IGA score ≥2 (28 of the 123 [22.8%] SD patients and 14 of the 75 [18.7%] AD patients). Early exclusion occurred because of changes in blinded study medications (3 of the 40 SD patients and no AD patients), noncompliance (7 of the 40 excluded SD patients and 10 of the 26 excluded AD patients), and prohibited medication (2 of the 40 SD patients and 2 of the 26 AD patients) (Fig. 3).

A total of 27 SD patients (30.0%) and 15 AD patients (20.0%) experienced adverse events that were assessed by the investigators of this study. Burning sensations, erythema, folliculitis and pruritus at application sites were common adverse events, some of which were overlapped each other (Table 1). Among these, six SD patients and five AD patients wanted to be withdrawn from the study because of adverse events.

Of the 198 phase I patients, 132 (83 SD patients and 49 AD patients) were enrolled in phase II (Fig. 1). The demographics of the enrolled patients are presented in Table 2. There were no significant differences between the AD and SD groups in demographic and baseline characteristics except for the mean age (Table 2).

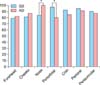

The recurrence-free curves of the two groups are shown in

Fig. 4. Fifty-four patients (65.0%) in the SD group and 32 patients (65.3%) in the AD group had no DE during the 20 weeks of phase II (Fig. 4). In the previous study24, all of the 10 patients of the placebo group had DE (IGA ≥2) in 10 weeks. Eight patients of the placebo group had DE at 2 weeks, one patient at 4 weeks, and the other one patient at 6 weeks.

The recurrence-free curves of the two groups of our study were not significantly different from each other at each visit; however, the curve of the placebo group of the previous study was significantly different (p<0.05 by log rank analysis) from both groups of our study (Fig. 4).

Kaplan-Meier analysis was also performed to evaluate the recurrence-free times of each facial region. The recurrence-free curves were similar between the two groups in the forehead, cheeks, chin, and perioral/periauricular regions. On the other hand, the perioral region tended to have recurrences earlier in facial AD patients and the nose in facial SD patients. The cumulative disease-free rate of patients (IGA≤1) at 20 weeks of phase II was 63.6% for facial SD and 63.5% for facial AD, and that of the placebo group was 0% for facial SD (Fig. 5).

The number of DEs was also not significantly different between the two groups (p=0.98). The results of age-stratified analysis (Mantel-Henzel χ2 test; ages, 19, 20~39, 41~59, and ≥60 years) were constant. The median time to first DEs was not significantly different between the two groups (mean±standard deviation: 41.17±26.41 days vs. 40.55±24.84 days; p=0.38). In the previous study, the median time to first DE of the placebo group was 18.20±9.44 days24. It was shown that the median time to the first DE of both groups of our study were longer than that of the placebo group of the previous study, although the maintenance period was different (20 weeks vs. 10 weeks). The mean IGA scores for the first DE (2.12±0.33 vs. 2.17±0.38 vs. 2.90±1.10) were not significantly different between the three groups (p=0.51 by one-way ANOVA). Also, the mean VAS scores for the first DE (2.96±1.68 vs. 3.31±1.11) did not differ significantly between the two groups (p=0.84).

During phase II, there were no significant differences between the two groups in the incidences of application-site adverse events. Fifteen patients (18.1%) in the SD group experienced adverse events during phase II, whereas nine patients (18.4%) in the AD group experienced adverse events, such as pruritus (five SD patients, 6.0% vs. three AD patients, 6.1%), irritation (four SD patients, 4.8% vs. two AD patients, 4.1%), folliculitis (three SD patients, 3.6% vs. two AD patients, 4.1%), and erythema (three SD patients, 3.6% vs. two AD patients, 4.1%) (Table 1). None of the patients expressed a desire to quit the clinical trial because of their adverse events during phase II.

In this study, the efficacy and tolerability of a 20-week maintenance therapy with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment were compared between two diseases-facial SD and facial AD. Our results demonstrated that the efficacy and safety of tacrolimus treatment were not significantly different between the two diseases. There were no significant differences between the two groups in the time to the first DE episode, number of DEs, and treatment days for DEs. The adverse event profile was also similar between the two groups. During the 20 weeks of treatment, the study population tolerated tacrolimus ointment well.

Previous trials have indicated that maintenance therapy with tacrolimus is more successful in preventing AD flares than reactive vehicle treatment131825. Previous studies with a similar protocol used maintenance therapy or proactive treatment 18192426. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of maintenance therapy with TCI for SD. The immunological justification of maintenance therapy is based on the fact that seemingly normal skin in patients with eczema, such as AD or SD, actually often shows barrier defects and subclinical inflammation2. Thus, maintenance therapy applied to previously involved skin is essential for the prevention of disease relapse. The preferred sites for the application of TCIs are the face, neck, and flexures, which are most susceptible to the adverse effects of TCSs. In addition, TCIs have been found to be active against fungal strains, including Malassezia furfur and various other Malassezia strains that are closely related to the pathophysiology of SD2728. Therefore, TCI was chosen for maintenance therapy in this study20.

This is the first study that statistically evaluated the recurrence-free times of each facial region and compared the results between AD and SD. The recurrence-free curves were similar between the two groups in the forehead, cheeks, chin, and perioral/periauricular region. Otherwise, the eczematous lesions in the perioral region of AD patients and in the nasal area of SD patients relapsed earlier compared with the others. Periorbital and perioral dermatitis were more frequent in AD patients than in SD patients, whereas SD tends to occur in regions with a high production of sebum and areas that have cutaneous folds. These results are partially consistent with those of previous studies; however, further studies with more data would be required.

Compared with pimecrolimus cream, there have been fewer trials about the efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment in the treatment of SD2329. Nevertheless, tacrolimus ointment was chosen in the current study because some previous studies showed that tacrolimus ointment was more clinically effective than pimecrolimus in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe AD30313233; however, other studies showed a similar efficacy34. Furthermore, we hypothesized that patients would be able to endure the greasy texture if they only had to apply the ointment only two nights per week.

The duration of this trial was relatively short for a study on maintenance therapy, and there was also a shortcoming in the assessment of long-term efficacy and the adverse effects of maintenance therapy with TCI for the treatment of SD. Future studies are needed to evaluate the long-term safety of maintenance therapy with TCIs in SD and AD patients. Another limitation is that there was no vehicle group in our study. To compensate for these limitations, we directly compared our data with those of the placebo group of a recent study on the same racial group and of a similar design. Also, there were differences in the average age between the SD group and AD group patients. This bias occurred because the frequent onset age of SD is higher than that of AD. To correct this difference, a comparison was done by dividing patients into age groups, and no difference was found among the different age groups.

In summary, maintenance therapy with tacrolimus ointment was effective and well tolerated in preventing flares of facial SD and facial AD compared with a vehicle. The results of this study may help establish a standard maintenance TCI treatment regimen, and support the development of effective therapeutic approaches for the prevention of DEs in SD patients.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

Clinical measures evaluated in 7 divided facial parts (forehead, periorbital, nose, chin, cheeks, perioral and periauricular).

Fig. 3

Flow diagram. Total 195 patients are enrolled and 112 patients completed the clinical trial. Forty (32.5%) patients in the seborrheic dermatitis group and 26 (34.7%) patients in the atopic dermatitis group discontinued the study during the phase I.

Fig. 5

Percentage of patients with investigator global assessment ≤1 in 7 divided facial parts during phase II (*p<0.05). SD: seborrheic dermatitis, AD: atopic dermatitis.

Table 1

Incidence of the most common* causally related† adverse events during phase I and II

Values are presented as number only or number (%). *Reported in at least 3% of the total patients or 3% in either group. †Causally related is defined as being assessed by the investigator as having a highly probable, probable, possible, or nonassessable relation to the study drug, or missing assessment of the relation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2014R1A1A3A04049491), and Hallym University Research Fund 2014 (HURF-2014-53, HURF-2014-58).

References

1. Aschoff R, Kempter W, Meurer M. Seborrheic dermatitis. Hautarzt. 2011; 62:297–307.

2. Cook BA, Warshaw EM. Role of topical calcineurin inhibitors in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis: a review of pathophysiology, safety, and efficacy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009; 10:103–118.

3. Faergemann J, Bergbrant IM, Dohsé M, Scott A, Westgate G. Seborrhoeic dermatitis and Pityrosporum (Malassezia) folliculitis: characterization of inflammatory cells and mediators in the skin by immunohistochemistry. Br J Dermatol. 2001; 144:549–556.

4. Bikowski J. Facial seborrheic dermatitis: a report on current status and therapeutic horizons. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009; 8:125–133.

5. Gupta AK, Nicol K, Batra R. Role of antifungal agents in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004; 5:417–422.

6. Shemer A, Kaplan B, Nathansohn N, Grunwald MH, Amichai B, Trau H. Treatment of moderate to severe facial seborrheic dermatitis with itraconazole: an open non-comparative study. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008; 10:417–418.

7. Darabi K, Hostetler SG, Bechtel MA, Zirwas M. The role of Malassezia in atopic dermatitis affecting the head and neck of adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009; 60:125–136.

8. Kolmer HL, Taketomi EA, Hazen KC, Hughs E, Wilson BB, Platts-Mills TA. Effect of combined antibacterial and antifungal treatment in severe atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996; 98:702–707.

9. Rigopoulos D, Ioannides D, Kalogeromitros D, Gregoriou S, Katsambas A. Pimecrolimus cream 1% vs. betamethasone 17-valerate 0.1% cream in the treatment of seborrhoeic dermatitis A randomized open-label clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2004; 151:1071–1075.

10. Anstey A. Management of atopic dermatitis: nonadherence to topical therapies in treatment of skin disease and the use of calcineurin inhibitors in difficult eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2009; 161:219–220.

11. Tatlican S, Eren C, Oktay B, Eskioglu F, Durmazlar PK. Experience with repetitive use of pimecrolimus: exploring the effective and safe use in the treatment of relapsing seborrheic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010; 21:83–85.

12. Schmitt J, von Kobyletzki L, Svensson A, Apfelbacher C. Efficacy and tolerability of proactive treatment with topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors for atopic eczema: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Dermatol. 2011; 164:415–428.

13. Wollenberg A, Reitamo S, Girolomoni G, Lahfa M, Ruzicka T, Healy E, et al. European Tacrolimus Ointment Study Group. Proactive treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Allergy. 2008; 63:742–750.

14. Breneman D, Fleischer AB Jr, Abramovits W, Zeichner J, Gold MH, Kirsner RS, et al. Tacrolimus Ointment Study Group. Intermittent therapy for flare prevention and long-term disease control in stabilized atopic dermatitis: a randomized comparison of 3-times-weekly applications of tacrolimus ointment versus vehicle. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008; 58:990–999.

15. Hoeger PH, Lee KH, Jautova J, Wohlrab J, Guettner A, Mizutani G, et al. The treatment of facial atopic dermatitis in children who are intolerant of, or dependent on, topical corticosteroids: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2009; 160:415–422.

16. Gupta G, Mallefet P, Kress DW, Sergeant A. Adherence to topical dermatological therapy: lessons from oral drug treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2009; 161:221–227.

17. Papp KA, Papp A, Dahmer B, Clark CS. Single-blind, randomized controlled trial evaluating the treatment of facial seborrheic dermatitis with hydrocortisone 1% ointment compared with tacrolimus 0.1% ointment in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012; 67:e11–e15.

18. Thaçi D, Reitamo S, Gonzalez Ensenat MA, Moss C, Boccaletti V, Cainelli T, et al. European Tacrolimus Ointment Study Group. Proactive disease management with 0.03% tacrolimus ointment for children with atopic dermatitis: results of a randomized, multicentre, comparative study. Br J Dermatol. 2008; 159:1348–1356.

19. Wollenberg A, Ehmann LM. Long term treatment concepts and proactive therapy for atopic eczema. Ann Dermatol. 2012; 24:253–260.

20. Luger T, Paul C. Potential new indications of topical calcineurin inhibitors. Dermatology. 2007; 215:Suppl 1. 45–54.

21. Kim BS, Kim SH, Kim MB, Oh CK, Jang HS, Kwon KS. Treatment of facial seborrheic dermatitis with pimecrolimus cream 1%: an open-label clinical study in Korean patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2007; 22:868–872.

22. Ozden MG, Tekin NS, Ilter N, Ankarali H. Topical pimecrolimus 1% cream for resistant seborrheic dermatitis of the face: an open-label study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010; 11:51–54.

23. Meshkinpour A, Sun J, Weinstein G. An open pilot study using tacrolimus ointment in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003; 49:145–147.

24. Kim TW, Mun JH, Jwa SW, Song M, Kim HS, Ko HC, et al. Proactive treatment of adult facial seborrhoeic dermatitis with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment: randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, multi-centre trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013; 93:557–561.

25. Fukuie T, Nomura I, Horimukai K, Manki A, Masuko I, Futamura M, et al. Proactive treatment appears to decrease serum immunoglobulin-E levels in patients with severe atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2010; 163:1127–1129.

26. Poole CD, Chambers C, Sidhu MK, Currie CJ. Health-related utility among adults with atopic dermatitis treated with 01 tacrolimus ointment as maintenance therapy over the long term: findings from the Protopic CONTROL study. Br J Dermatol. 2009; 161:1335–1340.

27. Sugita T, Tajima M, Tsubuku H, Tsuboi R, Nishikawa A. A new calcineurin inhibitor, pimecrolimus, inhibits the growth of Malassezia spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006; 50:2897–2898.

28. Sugita T, Tajima M, Ito T, Saito M, Tsuboi R, Nishikawa A. Antifungal activities of tacrolimus and azole agents against the eleven currently accepted Malassezia species. J Clin Microbiol. 2005; 43:2824–2829.

29. Braza TJ, DiCarlo JB, Soon SL, McCall CO. Tacrolimus 0.1% ointment for seborrhoeic dermatitis: an open-label pilot study. Br J Dermatol. 2003; 148:1242–1244.

30. Paller AS, Lebwohl M, Fleischer AB Jr, Antaya R, Langley RG, Kirsner RS, et al. US/Canada Tacrolimus Ointment Study Group. Tacrolimus ointment is more effective than pimecrolimus cream with a similar safety profile in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: results from 3 randomized, comparative studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005; 52:810–822.

31. Fleischer AB Jr, Abramovits W, Breneman D, Jaracz E. US/Canada Tacrolimus Ointment Study Group. Tacrolimus ointment is more effective than pimecrolimus cream in adult patients with moderate to very severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2007; 18:151–157.

32. Yin ZQ, Zhang WM, Song GX, Luo D. Meta-analysis on the comparison between two topical calcineurin inhibitors in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2012; 39:520–526.

33. Abramovits W, Fleischer AB Jr, Jaracz E, Breneman D. Adult patients with moderate atopic dermatitis: tacrolimus ointment versus pimecrolimus cream. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008; 7:1153–1158.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download